Students

Ossama Anis

A bioengineering student who is excited about this opportunity in the Clinical Immersion Program in order to further my knowledge in a clinical setting. I look forward to determining the needs in which us bioengineers can enhance the technology and equipment utilized in the medical field in the most innovative ways. Keep up with my blog to witness my adventures in Interventional Radiology (IR) and Orthopedics!

Ossama Anis Blog

Ossama Anis Blog

Interventional Radiology: First Blog Entry

Ossama Anis Blog

Monday, July 6, was the first day of our participation in the Clinical Immersion Program. My partner Wali and I were given the opportunity to observe the Interventional Radiology (IR) department of the University of Illinois Hospital. The first few days of the program definitely lived up to my expectations. Dr. Bui and the rest of the radiology staff were all nice and extremely welcoming. The staff members introduced themselves and explained things to us in between surgical procedures. The doctor himself was very calm when conducting his daily rounds. He also communicated and explained the procedures while he was performing them.

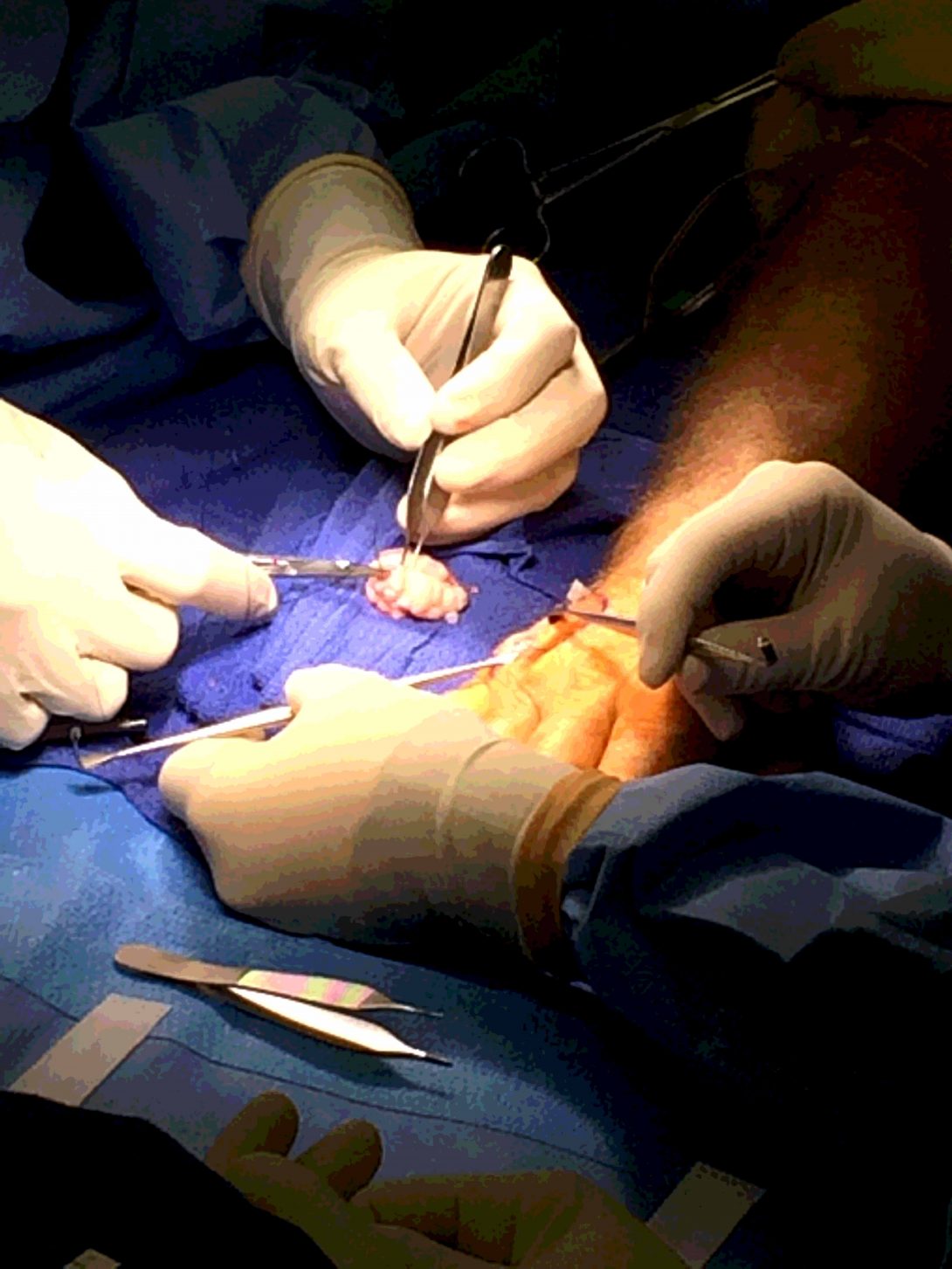

On the first day of the program, my partner and I were able to observe Dr. Bui performing a biopsy on a patient. An ultrasound was utilized to locate the tumor using sound pressure waves to create an image. Dr. Bui used a biopsy gun to extract a tissue sample from the given location. This biopsy gun is shown below followed by the extraction process.

The gun is inserted into the determined location. Once it is placed into the tissue, the trigger is pulled and the tip is released, the space between is sliced, clutching onto the desired sample.

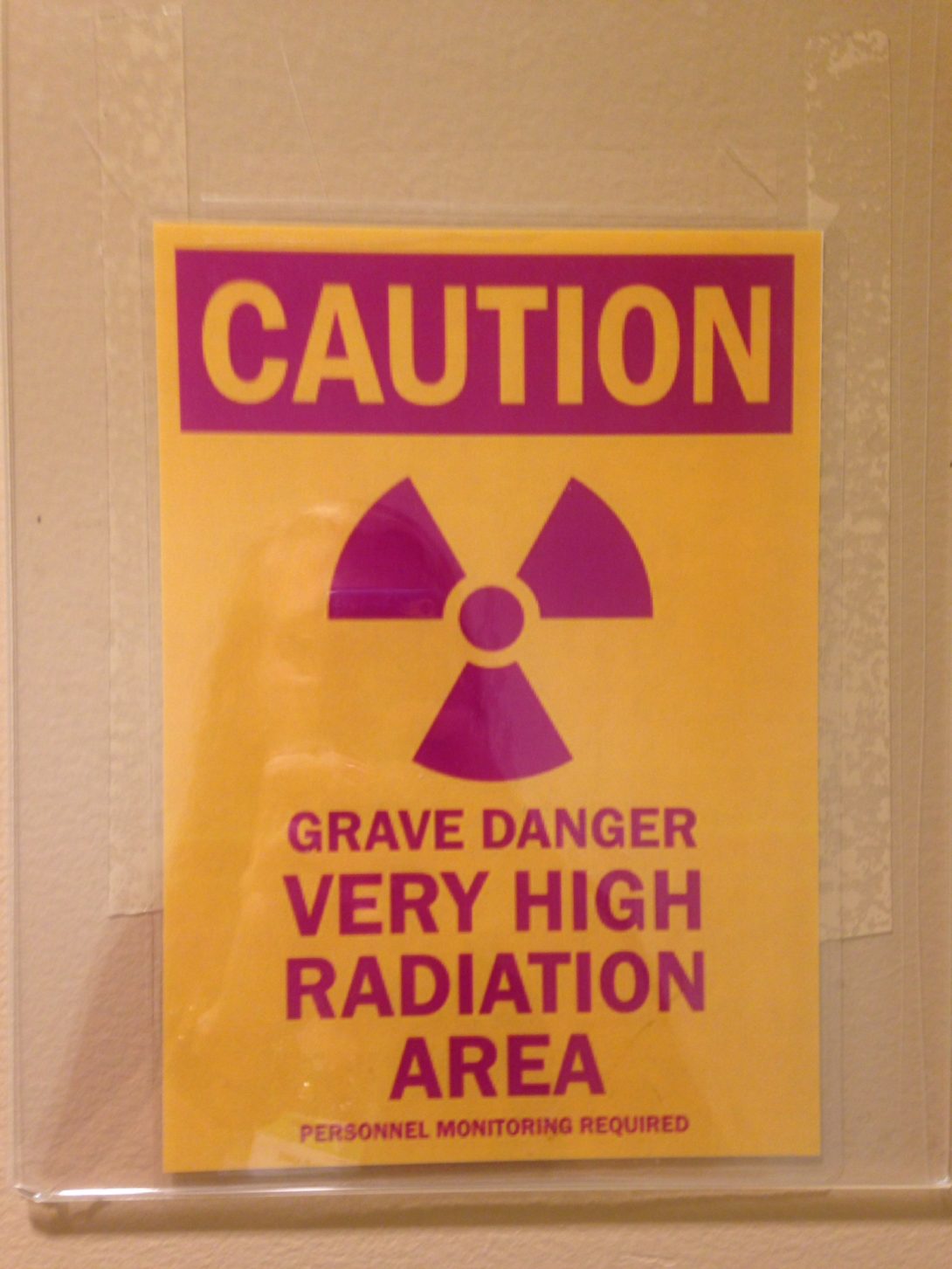

Following the biopsy, we went to observe another case. Here, we were instructed to stand outside the room due to the fact that we were not wearing lead around our chest and waist while the x-ray machine was in use. Dr. Gaba, another physician that works in IR, revealed to us how chemotherapy is performed. He had two syringes containing two different substances. A syringe containing a concentrated chemotherapy medication is mixed with the contents of another syringe that contains a lipid-based solution using a simple connector (shown below).

After the two solutions were properly mixed to create an emulsifier, the doctor injected the mixed solution into the hepatic artery of the patient by way of a catheter. The patient showed signs of some pain and discomfort after the time of injection.

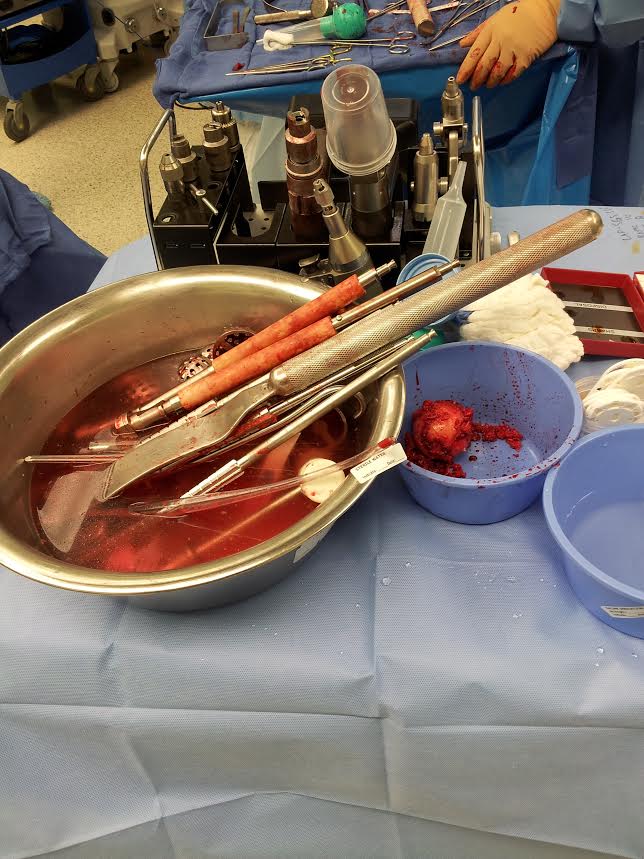

I made quite a number of observations while shadowing in the OR. We went into the OR where a number of physicians and nurses were stationed. The machinery is covered in disposable plastic sheets so that it does not get contaminated. I noticed there was a table that was prepped and sanitized. On it, we could see surgical tools, petri dishes, and a number of syringes. In the OR, the doctor observes a monitor that displays the most ideal version of the designated area in order for comparison. The doctor seems to have multiple monitors at his disposal. These monitors often times display the x-ray images of the area being treated. The nurses are ready to assist the doctor instantly and a few medical students are also watching the procedure. I noticed the tangled mess of electrical cords on the OR floor as this could be very hazardous.

My initial experience in the Clinical Immersion Program proved to be highly enlightening. Not only do these doctors handle the most delicate of procedures with complete ease, but they are eager to teach us bioengineers everything we need to know about the technology and equipment used along with the procedures being conducted. After day one, I’ve become very comfortable with Dr. Bui and asking questions at the appropriate times. I am extremely excited to learn more and looking forward to all the different experiences this program will bring.

Week One continued…

Ossama Anis Blog

The first week, my partner and I observed Dr. Bui performing a radiofrequency ablation procedure. This medical procedure ablates the tumor or other abnormal tissue using heat produced from high frequency alternating current. Dr. Bui used a Starburst Talon Device in order to destroy the tumor located in the patient. An ultrasound was utilized to locate the tumor in the liver. The Talon device was driven into the liver and the distal end of the device was placed directly in the middle of the tumor. After that, the four talons sprung out and each of them were heated to a temperature of 105° C. The device was held in place for nine minutes in order to destroy the tumor cells along with the surrounding tissue. The device shown below displays the temperature readings situated in a circle that represents each prong on the Talon.

My partner and I noticed that the Talon device did not look secure when the physician took his hands off of it. We thought that an improvement to this device would be to further secure it when it is heating and destroying the tumor. However, when addressing this to the doctor, we were told that the four prongs secure the device completely. The pictures below demonstrate the Talon device in both positions, prongs closed and prongs opened.

Another case that my partner and I observed was a patient with pancreatic cancer. Dr. Bui went over this patient’s CT scan while telling us about the biopsy procedure. He explained how he had to have the perfect placement of the needle in order to get a sample and study its’ pathology. The CT scan is performed first to find the correct needle placement. Then, this needle is used as guidance in order to obtain a biopsy sample. This case brought to light the importance of precision and how some cases come down to a matter of millimeters.

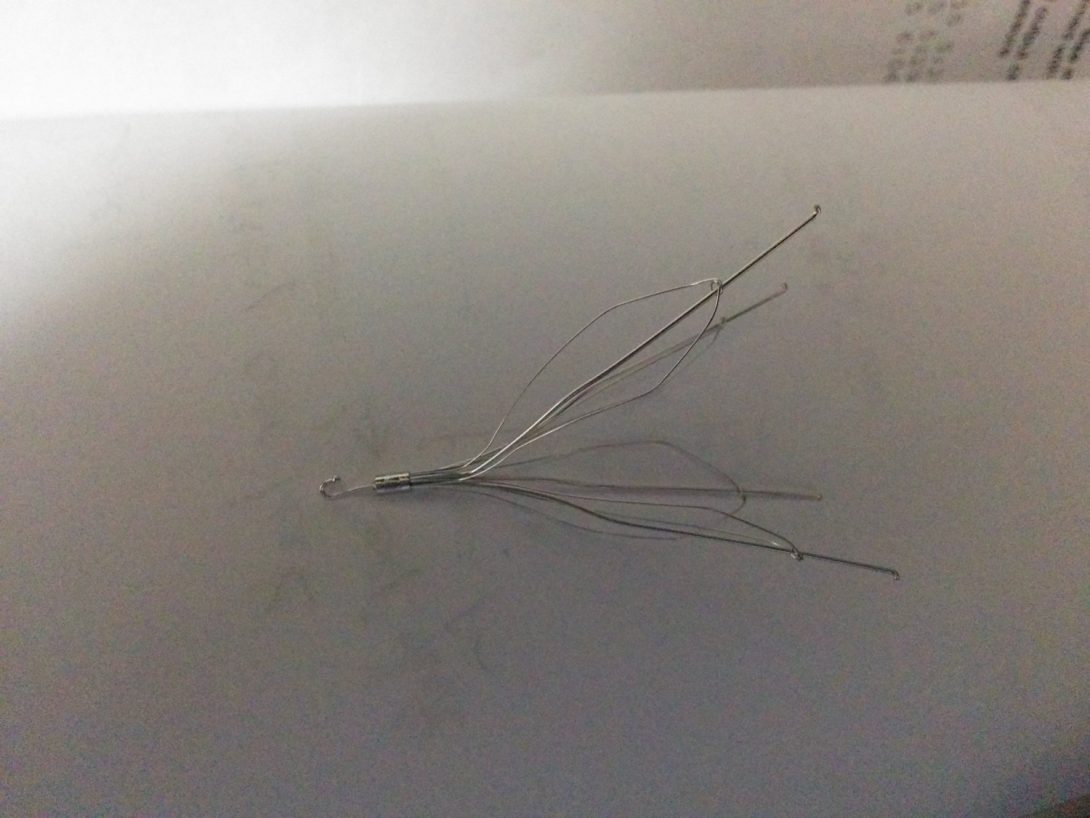

An interesting case we saw was a patient that was suffering from deep vein thrombosis. This is a condition in which blood clots reside in the deep veins of the leg or pelvis. Earlier in the day, Dr. Ray, another physician, had briefly spoken to us about filters that they place in a patient’s abdomen to assist with this condition. Filters are placed in the inferior vena cava (IVC) in order to break down blood clots that travel up from the veins of the leg or pelvis. These filters are vital in preventing blood clots from traveling to the lung or heart as this could result in pulmonary embolisms or even death. An example of this filter is pictured below. These cases brought to light the extreme amount of precision that is required in the clinical setting.

Week Two: Bone Biopsy and Embolization

Ossama Anis Blog

Week two is off to a great start. Observing the daily routines of these physicians is enlightening. One procedure my partner and I observed was a biopsy of the sacrum. The physician began by inserting a needle used for guidance into the back near the iliac crest. He then observed the patient’s CT scan in the axial view in order to assure it had been properly inserted into the sacrum. A drill, pictured below, was then utilized to cut through the tissue and into the bone in order to retrieve a sample. Observations made suggest an improvement in the way data is viewed, as a biopsy may be easier if the CT scan was observed in the sagittal and the axial view simultaneously.

Also observed was a patient with cancer in the kidney. The treatment for this patient consisted of microspheres being injected into the renal artery. This is a minimally invasive procedure in which microspheres block the flow of blood to the kidney. Once the microspheres are injected, they travel with the blood to the network of vessels that lead to the kidney. These microspheres block the blood flow leading to the tumor. This procedure is done in order to prevent growth and encourage shrinking of the tumor. Embospheres are microspheres that are heavily used in interventional radiology.

Embospheres are seen again in uterine fibroid-embolization (UFE). This process, pictured below, takes place when there is a benign tumor in the uterus. In this process, the catheter and stylet are placed into the uterus. Once in the desired location, a contrast, usually organically-bound iodine, is injected to assure the correct placement of the catheter. The embospheres are then injected and used to block the uterine artery in order to stop blood flow to the tumor. Uterine fibroid-embolization is the most common procedure that makes use of these embospheres.

Week Two: TIPS

Ossama Anis Blog

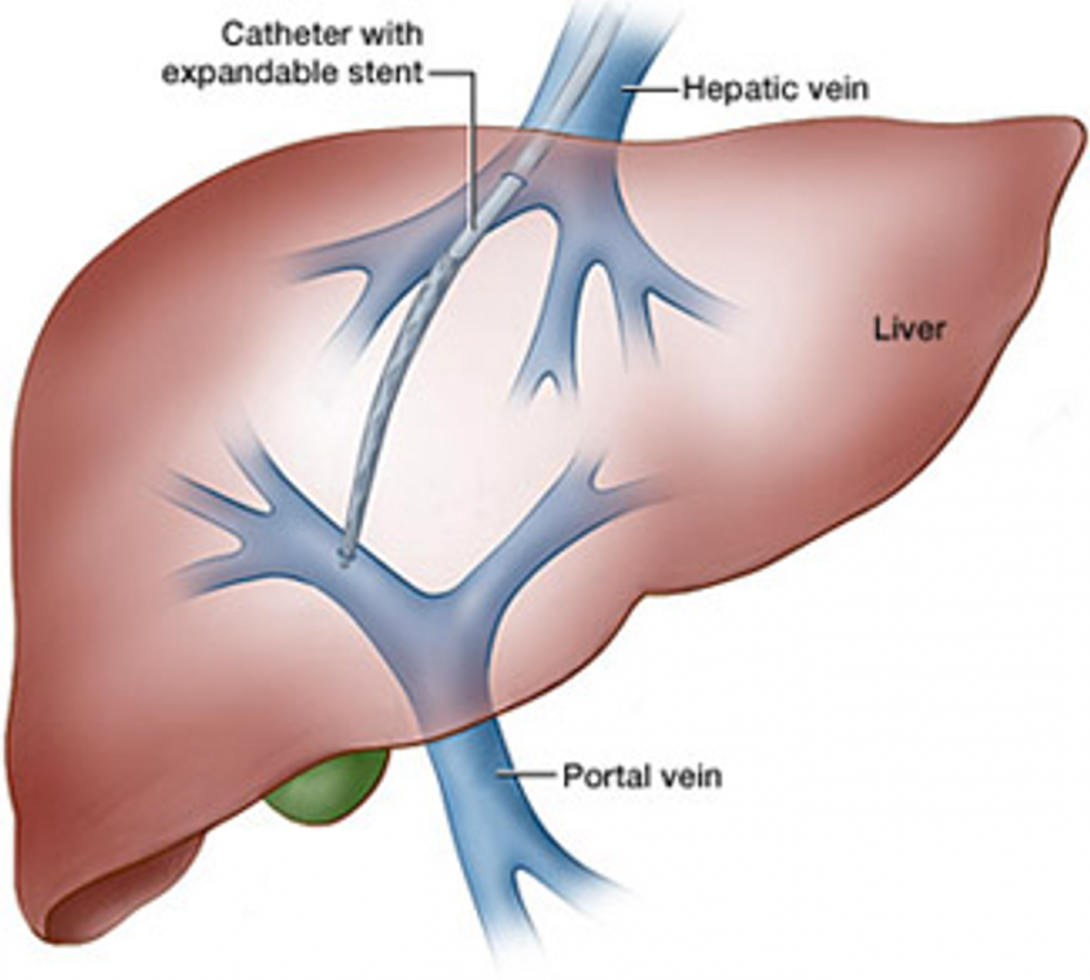

An interesting procedure we observed this week dealt with portal hypertension. Blood flows from the esophagus, stomach, and intestines through the liver. Damaged livers disrupt this flow and cause portal hypertension, which is the elevated pressure of the portal vein. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is a procedure that is used to create a connection between two blood vessels in your liver. The connection of these blood vessels, the hepatic vein and the portal vein, allow for relief of portal hypertension.

The physician conducts this procedure by observing the patient’s fluoroscopy. The patient was on his back and hooked up to heart and blood pressure monitors. This non-surgical procedure consisted of a catheter being inserted into the jugular vein in the neck. Using fluoroscopic visualization, this tube was guided into the portal vein. Once in proper position, the balloon was inflated to a specific pressure in order to dilate the path between the hepatic and portal veins. The physician then connected the portal vein to one of the hepatic veins. This connection relieves the portal hypertension. The pressure of the portal vein is observed using a pressure wedge in order to confirm the declination of pressure in the portal vein, thus declaring the procedure a success. The new pathway allows for blood flow to be regulated while easing the pressure on the organs involved.

This week has been a blast and I am looking forward to my final week in IR!

Week Three: PCN and Ureteral Stent

Ossama Anis Blog

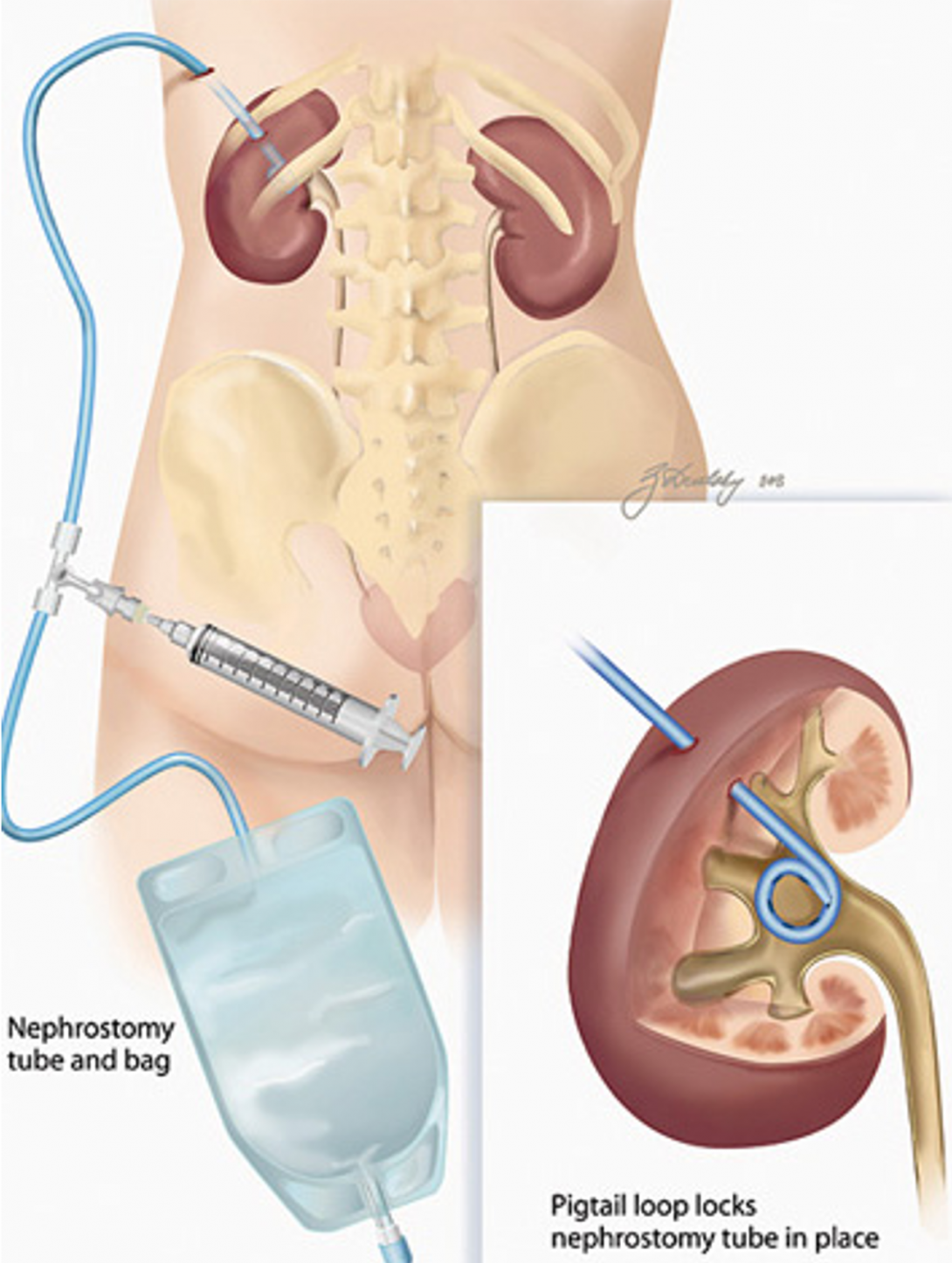

In the third week, Wali and I witnessed a physician perform a percutaneous nephrostomy (PCN). This procedure consists of gaining access to the kidney by placing a tube through the skin of the patient for drainage purposes. The doctor informed us that this procedure is often used to relieve the kidney of urine overload. In this procedure, access to the kidney for a catheter is granted percutaneously by using fluoroscopic guidance. After reviewing the patient’s medical condition, antibiotics were administered prior to the start of the procedure. The patient was sedated during the placement of the catheter.

To begin the process, Lidocaine was injected in the patient’s back near the kidney using an ultrasound as visual guidance. This needle is used as a guide for the placement of a nephrostomy tube, a specific catheter that travels from the incision to the kidney. After insertion, the stylet was removed, allowing for free flow of the renal tract. A drainage bag attached to the catheter was utilized to collect the urine.

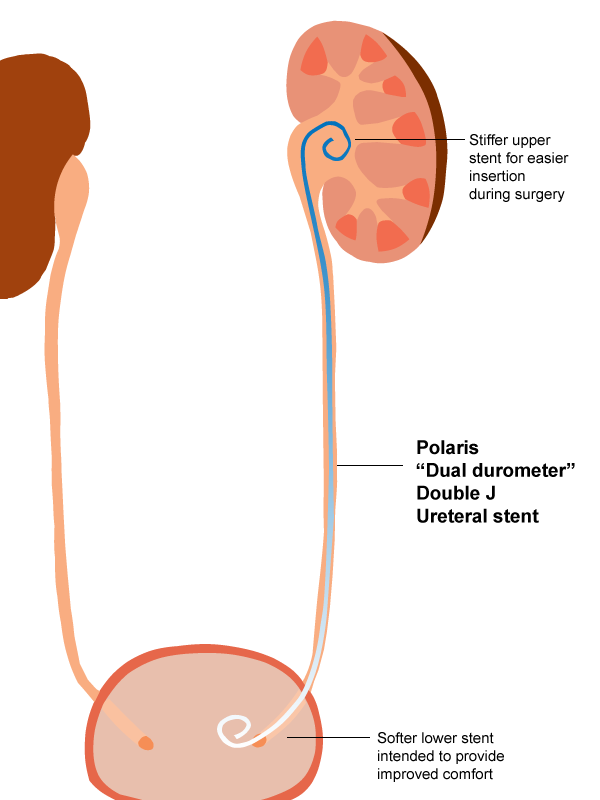

Another interesting case that we witnessed was a ureteral stent placement. This was performed on the first pediatric patient we have seen thus far. Due to a blockage in the ureter, there was an accumulation of urine in the kidney. A ureteral stent is a thin tube that allows urine to flow from the kidney and into the bladder. This stent is placed temporarily to prevent damage from occurring to the kidney. After the procedure was complete, we sat down with Dr. Ray and discussed the complications with this case. He explained how the ureteral stent was difficult to see under fluoroscopic guidance. For that reason, excess radiation was emitted to the patient in order for the physician to determine the location of the stent. We then discussed how coating methods may improve the visualization of the stent when using a fluoroscope.

Week Three: End of IR

Ossama Anis Blog

This week, we observed a chest port removal, a procedure which calls for anesthesia. This device is installed in the upper chest underneath the skin. A catheter is used to connect the device to a vein in order to administer medication. The modern ports, pictured below, are easier to remove and have two septems so they can be used twice as long. One of the physicians informed us that each septum can take about 2000 injections. Under the guidance of fluoroscopy, the interventional radiologist makes a small incision and removes the device. These ports are used for chemotherapy and hemodialysis as well as a variety of other uses.

We also witnessed a transjugular liver biopsy. The physician uses ultrasound as guidance and makes a small incision in order to insert a catheter into the jugular vein and into the liver. A biopsy needle is inserted in order to retrieve a tissue sample.

Interventional Radiology has been enlightening as to how important technology and imaging can be in the medical world. Thank you to Dr. Bui and the entire IR department for teaching us so much and making us feel welcomed! This experience is unforgettable and invaluable as it has opened my eyes to much of what is done in hospitals and things that could use some improvement.

Week Four: Orthopaedics!

Ossama Anis Blog

My next clinical rotation is in orthopaedics which has been very interesting thus far. I originally thought the department would be bombarded with surgeries, but Tiana and I haven’t seen any surgeries so far. Instead we shadowed Dr. Gonzalez, Dr. Shmell, and a couple residents in the clinic.

I definitely had more exposure to physician and patient interaction in these past two days than I did throughout my entire rotation in interventional radiology. It is a pleasure to see how Dr. Gonzalez diagnoses the patient and develops different treatment plans according to the patient’s lifestyle. I noticed him asking patients personal questions like where they work, if they lift heavy objects, etc.

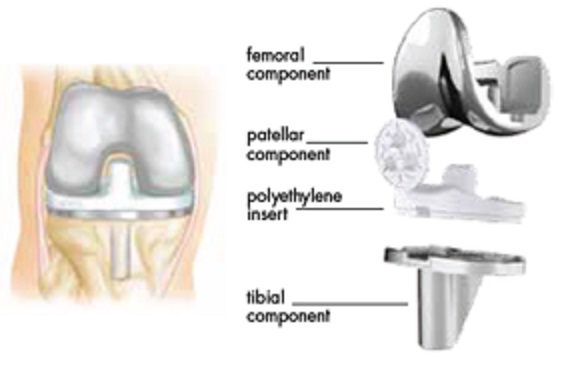

In between appointments, Dr. Gonzalez showed us an x-ray of a patient with a knee replacement. It consisted of two metal pieces, one attached to the femur and one to the tibia, and a wedge to diminish issues in between the two. He informed us on the issues with the wedge wearing away due to the excessive shear stress between wedge and the knee replacement. I noticed that the wedge is a darker shade of grey compared to the rest of the knee replacement obviously telling us that the material of the wedge is less dense than the counterparts.

One interesting case was a patient who came in regarding pain in his hand. The doctor said his hand looked like he had broken it a while ago because the bones in his hand were deformed. The patient then remembered that he may have originally broken it 10 years ago.The doctor informed the patient of the details about the procedure necessary to gain back the flexibility in his hand. It consisted of making an incision, breaking the deformed bones, taking some bone from the ilium, and screwing it all together. The doctor also said the hip may hurt more than the hand right after surgery. Another possible treatment is to take out the bad bone and bring the rest of the bones together. The fallback with this route is that it will take away 50% of the wrist’s mobility. The doctor said he has already lost about 50% for waiting a decade and causing a deformity.

On Tuesdays, we are to report to the 14th floor of the Crain Communications building, which is a skyscraper with a beautiful view of Millennium Park and the lake. On the first day, we met with Dr. Gonzalez and he took us out for lunch at The Gage. That was really nice of him, plus they had delicious food! Afterwards, we continued the day by going back to the clinic to attend to the rest of the patients. I am really enjoying orthopaedics so far and excited to observe surgery later this week.

Week Four: Joint Implants

Ossama Anis Blog

By the end of this week, we have seen a few surgeries in orthopaedics. The first procedure we observed was a total knee arthroplasty which consists of installing an artificial knee replacement. Many of the tools used, along with the knee replacement, were from Smith & Nephew.

The knee alignment device was positioned onto the lower leg to assure correct alignment before the cutting took place. A saw was used to shave off part of the proximal end of the tibia along with the distal end of the femur. A temporary knee replacement was used to help further assist the doctor with guidance for cutting, pinning, and drilling. Once the bones were carved to the correct shape for the knee replacement, cement manufactured by Stryker was applied. This acts as a glue between the bone and the knee replacement. Finally, the knee replacement was carefully inserted into the path created. Saline and Betadine were poured into the exposed knee and the opening was then sewed shut.

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic inflammatory disorder that causes pain and problems in the joints of the hand, sometimes requiring reconstructive hand surgery. Another case we saw dealt with a metacarpal phalangeal (MCP) joint prosthesis. The physician informed us on a scholarly resource that we can use to further explain details about this procedure and the equipment it requires. During this procedure, the physician removed the damaged joint and implanted an artificial joint made of silicone rubber. The implants have a stem that gets inserted into the bone on each end and a spacer in between the two components.

An incision was made on the proximal side of the knuckles. Then, part of the metacarpal and phalangeal bones were cut down using a saw. Afterwards, the joint was aligned and prepared for the installation of the implant. Trial implants were tested for size. Once the correct size was established, the stems on each part of the implants were inserted into the specified bones. The wound was treated with saline and antiseptic solutions and then sewn up. This procedure helps many rheumatoid arthritis patients who have deformities to their conditions.

People weren’t joking when they described orthopaedics as human carpentry. I noticed bone particles flying in the air when the saw was being utilized. I had a great first week in orthopaedics and can’t wait to see what else is in store for the final two weeks!

Week Five: At the Clinic

Ossama Anis Blog

During week five, a patient came in complaining about knee pain and how it got worse as the day went on. The doctor wanted to do a knee replacement but had concerns about her being overweight. Dr. Gonzalez then informed the patient of her BMI and the correlated data that has been accumulated, illustrating complications. These occur during total knee arthroplasty when the BMI is over 40. Blood clotting and infection are a couple of those complications. Since her BMI was right below 40, the surgery was scheduled to be in the first week of September.

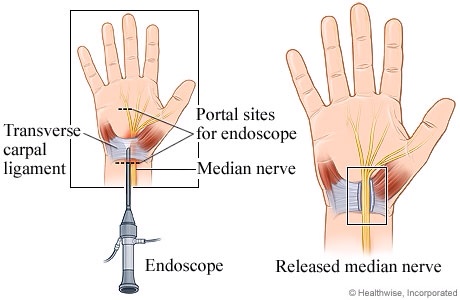

I noticed quite a few patients coming in regarding carpal tunnel syndrome. One, in particular, had a carpal tunnel reoccurrance due to the scar tissue that formed after the first surgery. This patient’s immune system produced more scar tissue than usual, thus resulting in the compression of the median nerve.

This syndrome occurs when the transverse carpal ligament presses down on the median nerve. The transverse carpal ligament holds the tendons and nerves in the hand together. However, after the surgery, the scar tissue replaces that function. A resident explained to us how Dr. Gonzalez performs surgery in order to relieve symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome. First, an incision is made and using endoscopic guidance, the transverse carpal ligament is cut with a small knife that is attached to the endoscope.

I’ve become really comfortable in the clinic atmosphere and having a great time learning something new every day.

Week Five: Knee and Hip Replacements

Ossama Anis Blog

By the end of this week, we observed three knee replacements and one hip replacement. The procedure for all of the knee replacements were done very routinely. First, an incision about 5 inches long is made and the patella is placed along the lateral side percutaneously. After aligning the tibia with a device called Knee Align, they screwed and pinned a slotted cutting guide. This guide contains a small slit where the saw is placed to create smooth, leveled surfaces. Once the tibia and femur were properly trimmed, trial components of various sizes were inserted to determine the correct size for the patient at hand. Dr. Gonzalez has experienced complications with the patellar component of the prosthesis, therefore he keeps the real human patella in the patient. Cement is used to adhere the prosthesis onto the bone, and the wound is then cleaned up and either stapled or stitched.

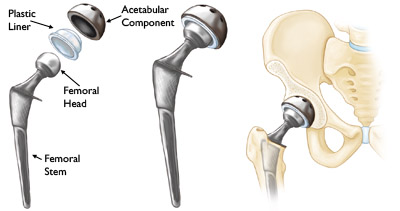

I was excited to watch the total hip arthroplasty since we haven’t watched it yet. Initially, an incision was made, about 4 to 5 inches long, and the femoral head was removed. Similarly to the knee replacement, trial components, from Depuy (a Johnson & Johnson company), were inserted to determine the correct size prosthesis. A plastic liner is used to separate the acetabular component from the femoral head in order to avoid contact between the two metals. Afterwards, the cut is sanitized and sealed.

The one day we had in the OR this week consisted of repetitive procedures. I wish we had at least two days observing surgery rather than one to allow for more exposure to the vast amount of cases and equipment this department has to offer. Although the clinic allows for much observation on physician patient interaction, the OR holds more of the knowledge bioengineers need to identify possible improvements.

Week Six: Last Week in Orthopaedics

Ossama Anis Blog

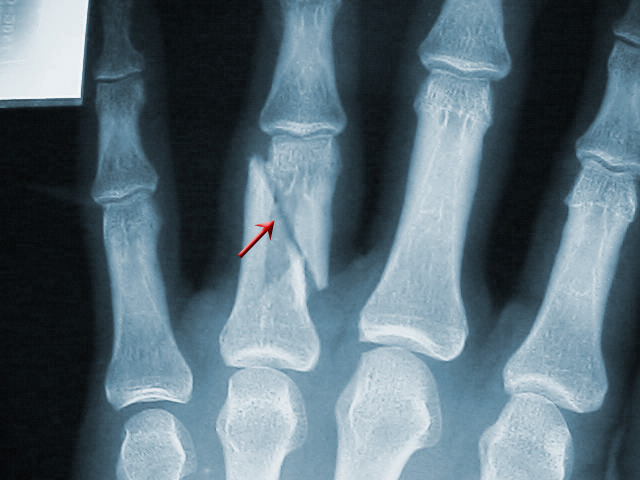

During my last week in orthopaedics, we followed up on a patient that came in two weeks ago concerning a fracture in her intermediate phalangeal. After taking a look at the x-ray, Dr. Gonzalez knew that the patient was going to have to undergo surgery. Since the patient did not come to the doctor immediately, the bone began to heal out of place. The surgery for this condition consists of making an incision, breaking the incorrectly healed phalangeal, aligning and placing the bones in correct form, securing the bones with a couple of screws, and finally sanitizing and stitching it all together. Surgery is necessary in order to prohibit the bone from healing incorrectly. Such conditions can interrupt the tendons and wear away the cartilage near the bone.

The patient in this case came in today for a follow up. Her surgery was last week. She is due to get her stitches removed about 2 weeks after the surgery. She is scheduled to keep a cast on for 6-8 weeks. The doctor instructed her not to lift weights because she will not have a good grip and may fall.

After shadowing physicians in this department, it is clear that they act conservatively. When a patient comes in regarding pain in their joints, the doctor tells them to attend therapy for 6-8 weeks. If they come back with pain, a steroid injection is administered. However, this only relieves pain temporarily. Injecting a steroid also has bad side effects such as wearing of the cartilage. Surgery is the final option physicians take when evidence and complaints indicate the patient is still in pain.

Ossama Anis Blog

My rotation in Orthopaedics came to a close along with the Clinical Immersion Program. I am extremely pleased with the vast amount of knowledge I have acquired in just six weeks!

On Thursday, our last day in orthopaedics, we were scheduled to watch a few surgeries, with a majority of them being hand procedures. The last case we observed in the orthopaedics OR consisted of a patient dealing with an infection in the hip. Dr. Gonzalez and the residents had to remove the original implant and insert an antibiotic spacer that releases a high dose of antibiotics into the joint and the surrounding tissue. A new prosthesis can be placed into the patient once the infection has cleared up. This individual may be more prone to a reoccurrence of an infection.

During the Orthopaedics rotation, we had a great deal of exposure to patient physician interaction. It was interesting to see how people had different pain tolerances. The doctor always wanted to start with therapy, followed by cortical steroid, and surgery if needed. Shadowing the doctor at the clinic was both interesting and enlightening. Each day he tended to about 20-80 patients, all with a wide range of symptoms and conditions. The other aspect of this rotation was in the OR and dealt with mostly invasive procedures. Here we observed all the different tools used, implants, and a wide range of procedures on various parts of the body. Orthopaedics was a great opportunity to get exposure to both clinic and OR aspects.

My time in Interventional Radiology was spent almost entirely in the OR. The ORs of the my rotations were very different. The orthopaedic OR consisted of highly invasive procedures while interventional radiology made procedures less invasive by using imaging modalities. Both departments have their pros and cons while their appeal depends on what an individual prefers to observe. Both rotations gave me invaluable knowledge in the clinical setting. There are many problems in the medical world and this program helps identify which problems need to be addressed and the severity of the need to find the solutions to those problems. Being in the OR gives more opportunities for engineers to observe the equipment, tools, and devices used. This kind of exposure and thought process allows to help further identify complications and possible solutions.

Thank you to Dr. Kotche and everyone involved for providing us with this amazing opportunity and unforgettable experience.

Jagan Jimmy

I am an bioengineering undergraduate student at UIC. Luckily enough, I was able to be part of the Bioengineering Clinical Immersion Program this summer. Through this blog, I will be able to share my experiences as I rotate through the Urology and the Hematology/Oncology departments over the course of the next six weeks.

Jagan Jimmy Blog

Jagan Jimmy Blog

Scrubs!

Jagan Jimmy Blog

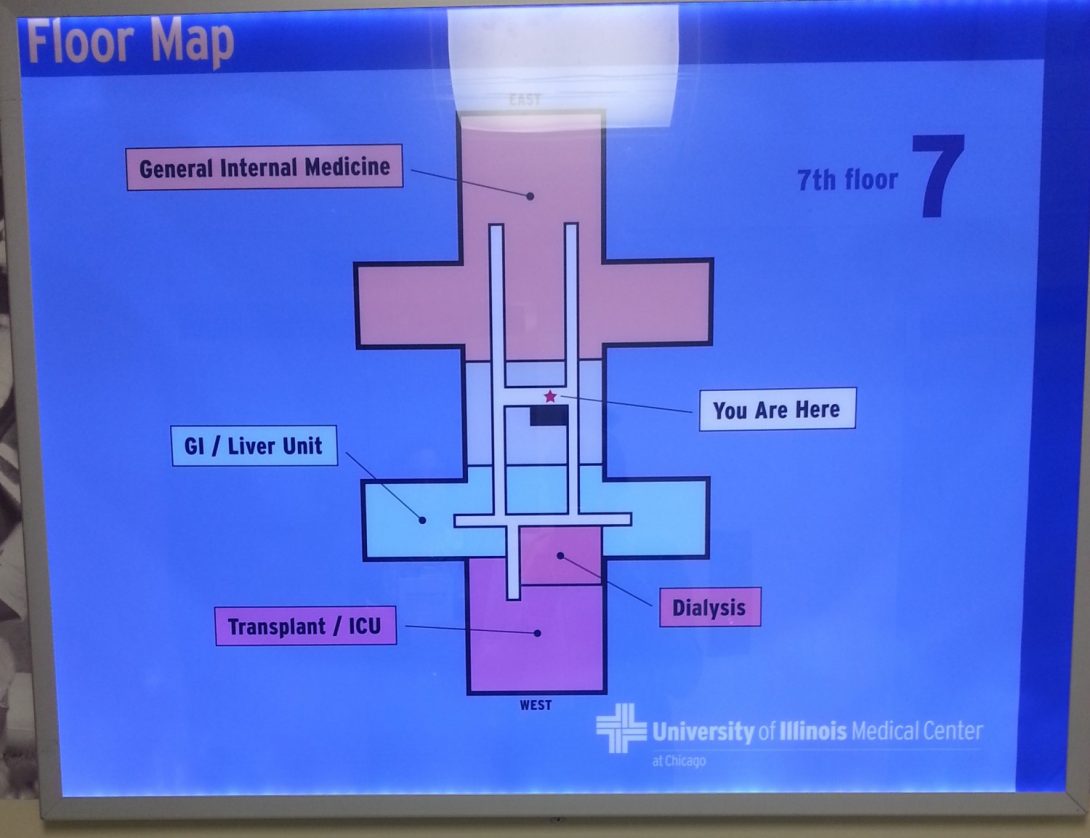

Upon going up to the third floor of the main hospital building, we were asked to change into scrubs and to put on a head and shoe cap just like everyone else there. After having done as we were told, with a pen, a clinical immersion notebook, and our cell phones we stepped out in to the hallway. Stepping out of the locker room immediately left us in the middle of the intersection of two main hallways where the OR information desk was located. The young lady at the desk, with the deep and serious expression, seemed tired and stressed. It wouldn’t be a surprise for anyone sitting in her position to be tired and stressed because she had two large monitors on her crowded desk, and numerous people approaching her for information. One of the screens was evidently reporting the status of all the operating rooms. The information about the department occupying the OR, the attending in there, and the procedure, among other color-coded information seemed to be displayed on it. On that single floor based on the screen alone, there seemed to be about 19 operating rooms. The second screen in front of the lady seemed to be where she is making appointments and such.

Nonetheless, upon asking in which ORs where the urology department operating, she quickly gave us two OR room numbers and resumed her work while answering about at least 2 people at the same time. Through the relatively crowded hallway we stumbled upon the first OR. An extremely small packed room. We knew it was the right place because peeking through the rectangular glass window of the door we could see a room half filled with machines and the other half filled up with people. The doctor seemed to be working on a female patient while various curious faces of medical students hoovered around observing the procedure. Since there were practically no room in there, we decided to check out the second OR the lady at the information desk told us. While finding the second OR, I couldn’t help but notice the amount of people passing through the hallways, some rushing through, some pushing huge medical devices I have never seen before, some with large carts full of OR instruments, and some just hanging on the sides for a small chit chat.

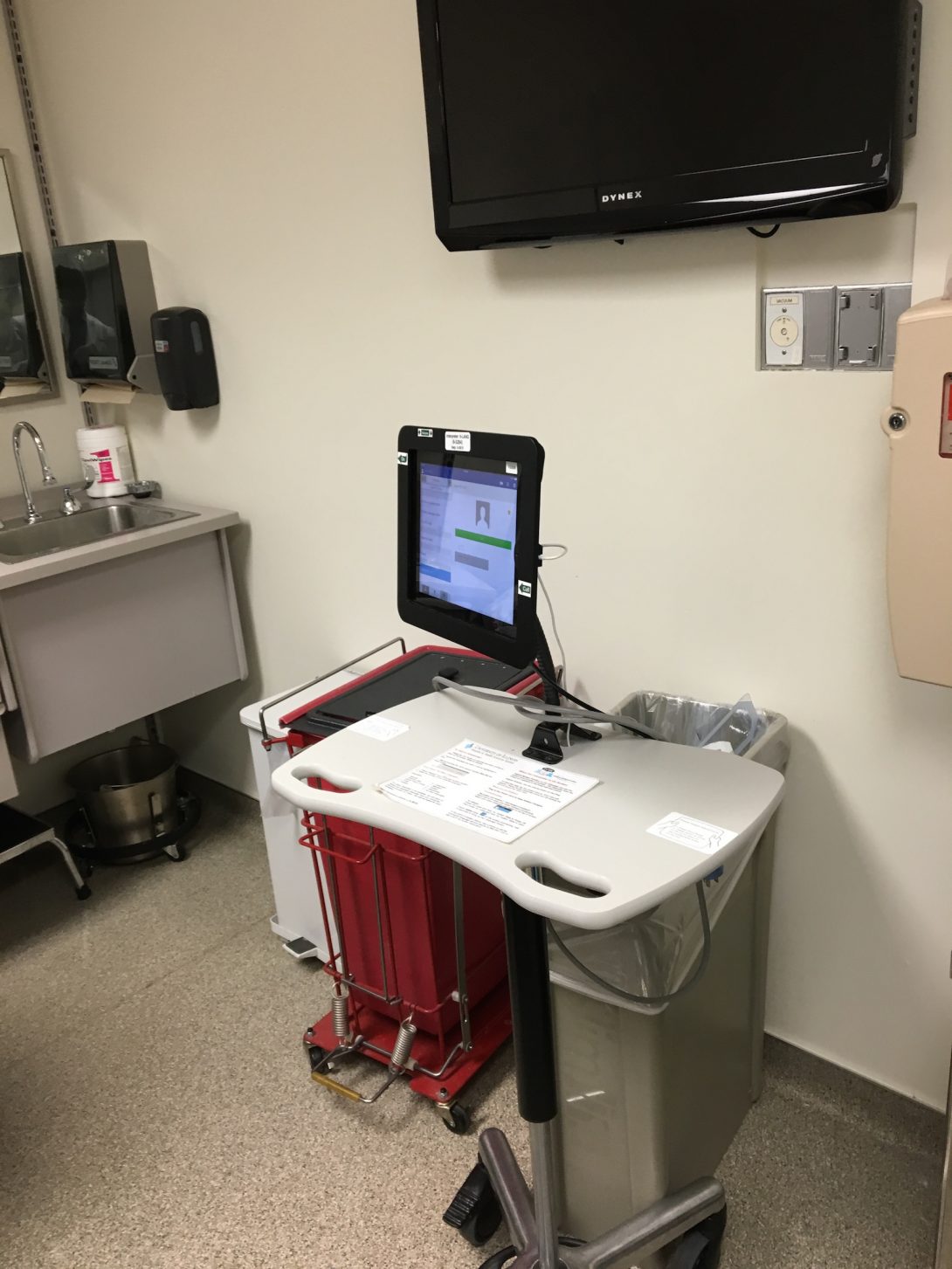

When we reached the second OR, there were no patient or doctor to be found in there, but instead only a few surgical nurses and a nurse anesthetist were present there. Upon chatting with them a bit we learned that a surgery had just finished and that they were prepping for the next patient that would be brought in within an hour or so. The patient would have been in the OR sooner, however they seem to have ingested some food thus had to wait for complete digestion of the food. Nevertheless, one of the nurses was kind enough to show us various machines in the room and their uses, she was willing to do so because the sterilized tools for the next surgery had been put out already thus by standard protocol a nurse has to be in the room to ensure that the sterilized wouldn’t be contaminated. An interesting term I heard from her as she was pointing out the various equipment was “energy devices”, which turned out to be surgical tools and machines that make use of some degree of current. A picture of the OR in which the nurse introduced my partner and I to the various equipment is shown here.

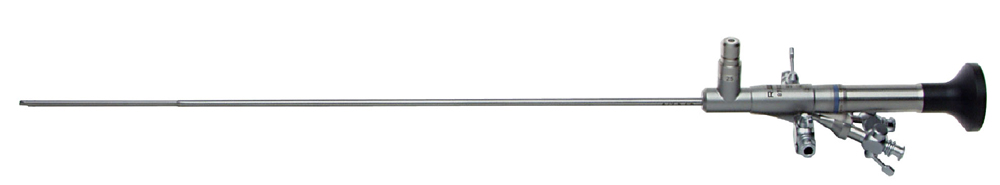

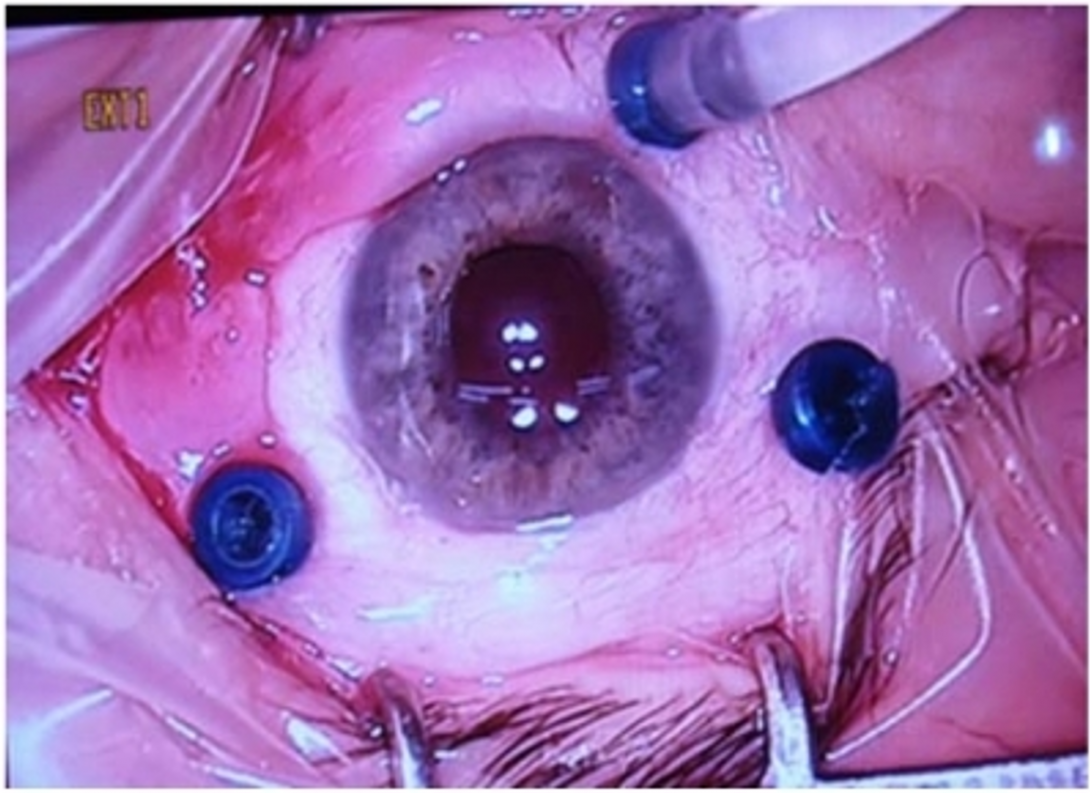

After our conversation with the surgical nurse, we returned to the OR we visited first. Thankfully, enough the surgeons and the medical student were standing outside because the x-ray technician had just brought in the x-ray machine and was setting it up. Meanwhile, we seized the opportunity to introduce ourselves to the medical students, residents, and the attending physician. The resident conducting the operation told us to come in to the OR, which would be about half of the size of the OR pictured above yet with almost all of the same equipment. However, in order to enter we were required to wear a leaded vest in order to protect ourselves from the radiation. Since the procedure being carried out at that point was a stent placement in the ureter to remove a kidney stone, which is a common procedure, some of the medical students didn’t bother to re-enter the OR, thus leaving my partner and I sufficient room in the OR to observe the procedure. The operating resident was using a resectoscope for the procedure, therefore the entire process was completed by looking at the visual provided by the camera on the resectoscope.

Following the procedure, most people in the OR moved to the larger OR that we had explored. This time an elderly gentlemen was brought in for a procedure known as Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). Given that it was a larger OR, it allowed a better view of the procedure and space for general observation. The case being operated was simply that there was a significant amount of scar tissue formation of the prostate gland around by the portion of the urethra that is close to the bladder. The scar tissue lead to obstruction of urine flow, which results in the buildup of the urine in the bladder; the buildup of urine could lead to further sever complications if not dealt with soon. The operating resident used a resectoscope to find the point of obstruction by inserting the resectoscope through the urinary meatus and sliding it through the urethra. The resident used the resectoscope to cauterize and remove the excess tissue gently and cleared the urethral pathway. The scarring was said to be due to the previous urological surgical procedure that the patient underwent. Nevertheless, while clearing the obstruction a few staples were found to be loosely hanging on the urethral wall – I found this to be interesting yet strange as I didn’t understand why they were placed in that part of the body in the first place. With that the, the resident finished up the work and was able to schedule the patient to leave home in the evening.

With the TURP procedure our first day in the OR came to an end. I was shocked to find that the surgical atmosphere was quite crowded in terms of the tools being used and the number of people involved in the procedure or simply observing. Nevertheless, it was an eye-opening experience to not only know the kind of task surgeons do on a daily basis but to also learn about the vast amount of surgical tools that have been engineered to make the surgical procedures minimally invasive and the safest.

I will be sharing with you more experiences from the OR and the urology clinic in my next post that will be posted within a day or two.

The remainder of the week

Jagan Jimmy Blog

The remainder of the week held even more exciting events than the first day. So far the schedule for the urology department is such that on Mondays, Thursdays, and Fridays are OR days when surgeries are performed. Tuesdays and Thursdays are clinic days during which the surgeons, residents, and medical students are all in the clinic and see patients while doing some minor procedures. The weekends are off days for the surgeon, and only emergency cases are attended to. Currently, the urology department is experiencing some technical difficulty seeing patient properly at the moment since they are relocating their clinic to a bigger building. Since the examination tools and other procedural tools haven’t been transferred to the new location the physicians simply sees patients on Tuesdays at the new location, and meet patients scheduled for simple procedure at the old location, where the tools are at. So Wednesday was more engaging and eventful that Tuesday. The old location that currently houses much of the department’s equipment is adjacent to the hematology/oncology clinic. An observer can easily see that because the two departments shares the clinic, the waiting area and the surroundings of the clinic are quite crowded.

While at the clinic we primarily just observed two procedures: cystoscopy, and transurethral biopsy. However, before I share an account of witnessing those procedures, I would like to share the insight we gained from the nurse working there. One of the male nurses at the clinic was generous enough to give us brief overview of the working of the clinic. He said that typically once a patient comes in they have to wait quite a while in the waiting area before bringing them in so that the nurse may prepare the procedure room. Note that these patients are the ones that are at the old locations where the department’s procedure tools still are at; therefore, the patients who came there already had an appointment. Once the nurse bring the patient to the procedure room, usually they give a brief overview of the procedure that is about to be done and addresses any concerns of the patient. Soon enough the patient is left to change in to a patient gown that’s more appropriate for the procedure. Then typically the patient waits there for anywhere from 30 minutes to an hour and sometimes more because they may be only one attending at the clinic. Since all patient seeing must be overseen by an attending, the resident cannot see the patient alone. Thus, during the long wait time the patient is usually left alone in the room, while the nurse checks in on them.

Another interesting observation that we made while we were there was that given the diversity of the area in which the hospital is located at, often the patients who comes in are not fluent in or doesn’t entirely speak English. In such cases, an interpreter is requested for the appropriate language. Having an interpreter present is an excellent choice since the patient wouldn’t feel so isolated and alone in the room among stranger; however, the drawback of it is that it can be time consuming because the interpreter needs to translate the doctor’s words and those of the patient. Nevertheless, the communication between the physician and the patient without the interpreter would be even more time consuming.

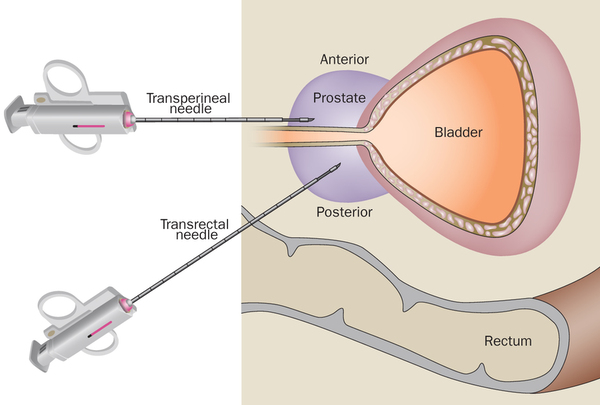

As mentioned above, the main procedures we observed were cystoscopy and transurethral biopsy. The resident (Dr. Tony) who carried out some of the procedures was helpful in explaining the procedure and the tools being used. Cystoscopy is simply an examination of the bladder. The procedure is done using a cystoscope. The biopsy was performed to obtain samples of the prostate to check whether the enlargement of the prostate was cancerous or not. In order to do so, an ultrasound probe was inserted into the anus of the patient to locate the spot. The ultrasound probe had an accessory that allowed the biopsy needle to be inserted and the ultrasound image shows where the needle is in relation to the prostate and from what angles to get the samples. An unfortunate need the nurse expressed is that the ultrasound probes are only available in the clinic in one size. Thus, for some patient the size of the probe can be a bit uncomfortable and painful.

Then during the last two surgical observation days we were able to observe some mind-blowing surgeries. One of the surgery was an explorative laparotomy. The patient was an elderly woman. The patient renal condition was critical because the right kidney was non-functional, and the left ureter being obstructed. Therefore, the previous surgery had connected the right ureter to the left kidney. However, due to the distance between the two parts the right ureter had two sharp turn to make before passing the urine into the bladder. Thus, the surgeons decided it is best to remove a portion of the bowel and create a ureter using that portion, and so they did. While doing so a tool that they used frequently is a sealer/divider. Basically a scissors that staples the edges of the two sides it cuts through to prevent bleeding. Nevertheless, the surgery took up almost the whole day because the surgeons took about 2 hours to simply cut into the peritoneal region due to many adhesions formed from previous surgery. Then it took them about an hour to properly reach the left kidney and locate it – the difficulty was primarily due to lack of visual. Once having done so they proceeded with the plane mentioned above. The surgeons were on their feet for about 7 hours until the urology surgeons could transfer the patient over to the general surgeons who dealt with the patient’s abdominal hernia.

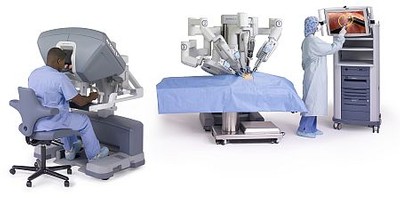

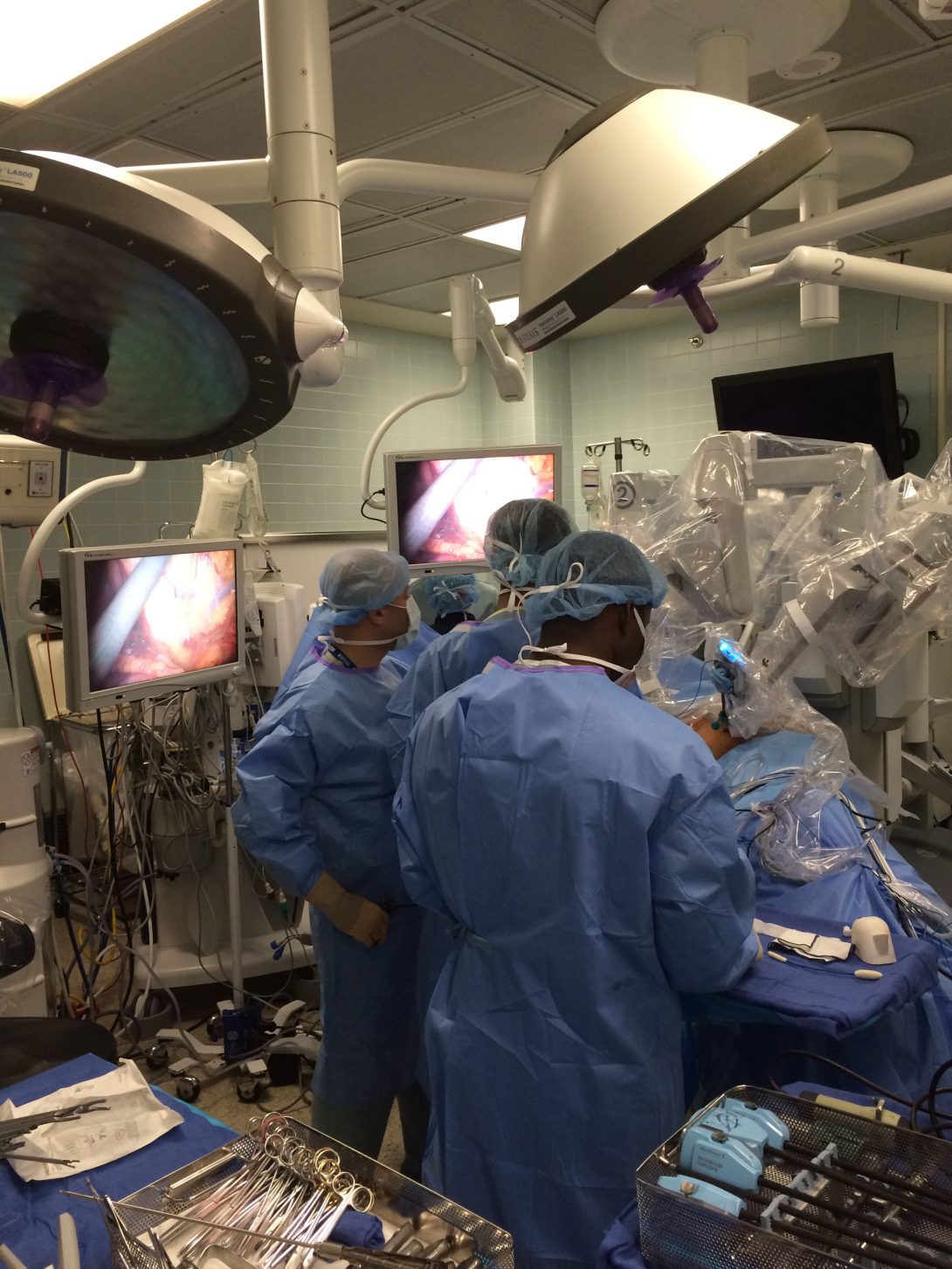

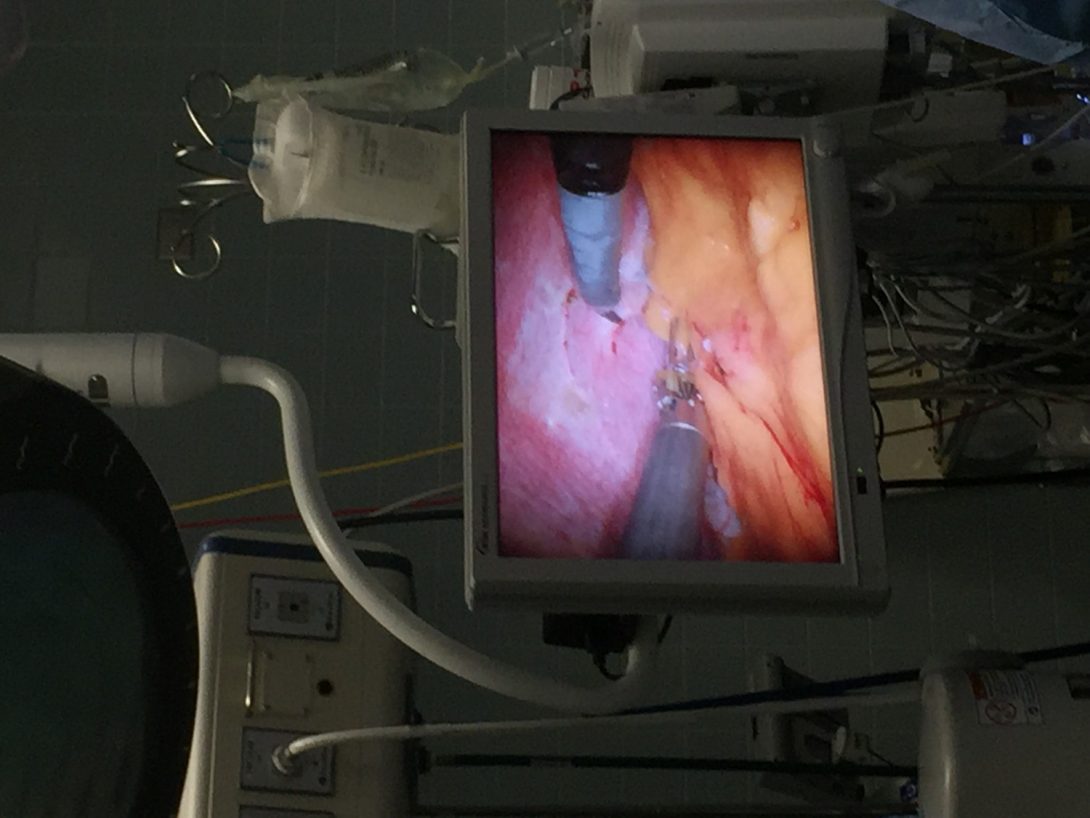

The following day we were able to see an adrenalectomy and partial nephrectomy carried out on a patient, and a prostatectomy on a second patient. What made these two cases quite exciting was the fact that they were both carried out by robotic laparoscopy. The Da Vinci robot is truly a magnificent device. In either case the surgeon made incisions on the patients and simply inserted the robotic arm with the tools that he would need while conducting the surgery. Often a resident would also be holding a tool laparoscopically so that they may practice the procedure while the robot (controlled by the attending) do the main portion of the surgery. The two main issues I have encountered are that because the attending sits at the control console of the robot that’s in the corner of the OR, while the resident with the manual probe/tool stays by the patient it is often a bit difficult to communicate between them due to the noise in the environment. Another flaw is that the da Vinci robot while being cutting edge technology fails to provide haptic feedback to the user. Inclusion of haptic feedback could in essence replicate the sense of touch the surgeon would have during open surgery.

With that, I’m going to stop the blog because to provide the fullest detail of the surgeries and the clinical procedures we observed would be a much longer post.

Note* the picture attached to this post is that of the Da Vinci robot. The picture I took which I wanted to upload seems to be too large such that I am unable to upload it.

Picture source: http://middlesexhospital.org/images/dmImage/StandardImage/450-da-vinci-system.jpg

Week 2 – First Half

Jagan Jimmy Blog

Week two of the clinical immersion in the urology department started out with even more surgeries for us to watch. I was able to observe placement of a suprapubic catheter, two lithotripsy procedures, and a circumcision. The suprapubic catheter was placed because the elderly patient was unable to have a catheter placed in her urethra. An odd act I noticed was that the attending physician was checking the placement of the catheter manually and ensuring it was in place without having a sterile gown or gloves on. This may be due to the fact that the procedure overall is a simply one, where the catheter is directly inserted into the bladder through an incision in the abdomen. The main downfall of having the procedure done is that the catheter is required to be replaced once every month and the abdominal incision remains open so long as the suprapubic catheter is in place.

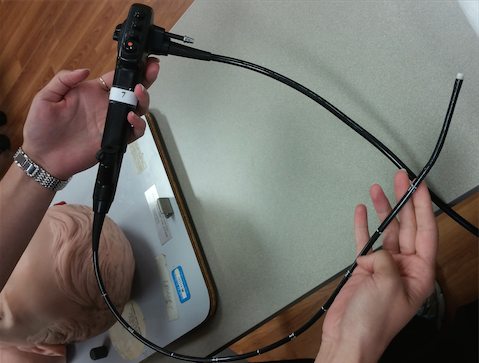

The lithotripsy is a procedure by which kidney stones are broken into smaller pieces using sound waves and then removed from the urinary system. In either case of lithotripsy it is standard to use a holmium laser – a laser that emits sound waves at a specific wavelength. One of the procedure had to use laser in order to crush the stones, however the other one didn’t require the use of the laser. The second lithotripsy didn’t require the use of the laser because the kidney stone descended down the ureter quite easily since the patient had a stent placement. The medical student informed us that usually in cases where the patient already have a stent placed in the ureter it is most likely that the stone will descend and not require the laser. Which made me wonder whether if such an occurrence is quite common then isn’t it a lot more efficient to hold back from opening the sterile container containing components of the laser once it use has been ensured. Additionally, the attending mentioned that with the various scopes that they use, whether it be cystoscope or a ureteroscope, the ones that have good flexibility are the thin ones however the weaker the irrigation capabilities and vice versa for the thicker probes. Nevertheless, the adult circumcision procedure that followed was quite straight forward. The procedure is primarily done using the traditional tools with the exception of using a cauterizing tool to remove the foreskin and stop the bleeding.

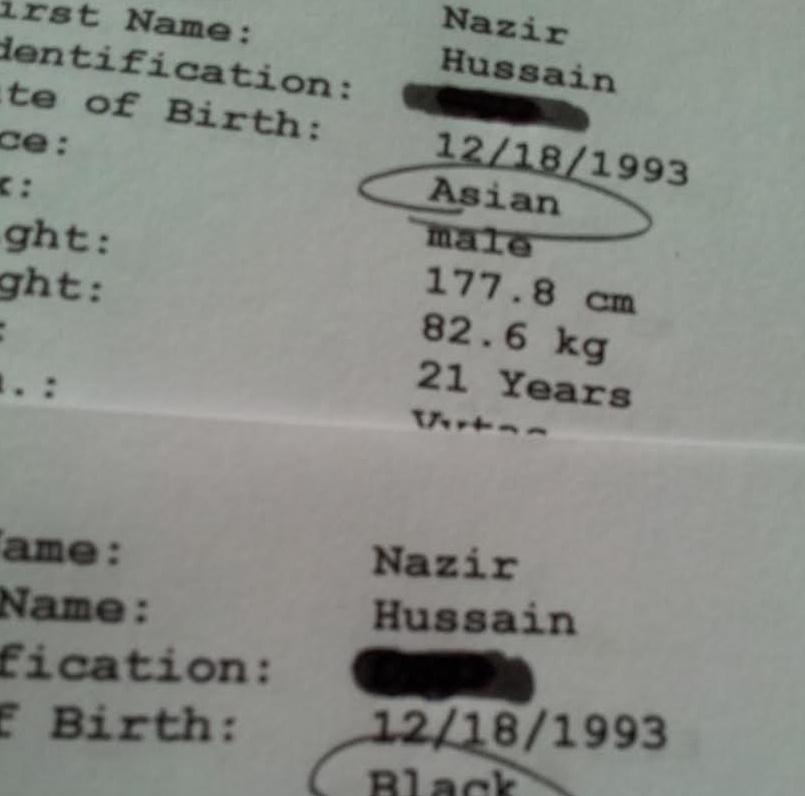

Then during our time at the clinic, which unfortunately isn’t as exciting as the OR, we were able to observe some patient-physician interaction. However note that the new location of the clinic, which was supposed to be fully equipped and functional by the first of this month, still lack the equipment to do the procedures. Nevertheless, the prior to the physician seeing the patient the medical students and/or the residents goes in and collect information from the patient and reports it back to the attending. Patients who have been with the UIH system has all their information available readily and structured in the Cernet system. However, patients with documents, scan results, etc. from clinical environments outside the UIH system has to bring it in with them and isn’t automatically transferred. For example one of the case we observed was that of an individual in their mid-forty. They had to carry around their CT scans throughout on a CD. I didn’t understand why the resident who collected the patient information didn’t simply upload the CT scan images under their name. Moreover, an interesting thing I noticed is that it took a while for the computers to load the CT scan results because there were hundreds of pictures. Had the clinic had computers with the latest high-speed processors I am sure the time to load imaging results (which are usually large files) can be decreased a lot. Lastly, one thing I noticed is that the doctors doesn’t seem to be the best at providing emotional care for the patients. It may be because that the doctors I observe are surgeons specialized in urology and they usually simply deal with surgery. But there does seem to be a lack of empathic connection between them.

Tune in for my experience with seeing two robotic surgery back to back and more in the next blog post. I have attached below a figure of the rigid cystoscope and ureteroscope so that you may see how the potential capabilities of either tool differs based on its physical structure – the thinner one is the ureteroscope.

More robotic surgeries..!

Jagan Jimmy Blog

The second half of the week is always more exciting than the first half because we get to spend more time observing surgeries. One of the interesting procedures we observed was varicochelectomy. The procedure is about simply the removal of the varicose veins around the testes. Given that it was a microsurgery, only two surgeons (residents) were operating on the patient at a time by using a microscope. The attending present at the surgery was generous enough to narrate the whole procedure. Once an incision of necessary size was made the tissue of interest was brought forward for better visual under the microscope. Under the microscope the operating surgeons examined the tissue to determine which of it were the arteries, veins, lymphatic vessels, and just fascia. This task seemed to be a bit difficult since they often look very much alike. Interestingly, enough they also used a Doppler ultrasound to distinguish between the artery and the other vessels. However, there seemed to be considerable ambient noises that results in the ultrasound being active. Upon further inquiry with medical students, they informed us that the microsurgeries cannot typically be done by robot assisted. Another interesting observation I made during the surgery was that when the sealer/divider ran out of staples, rather than reloading with the staple the entire tool was disposed and a new one was used. I found such discarding to be quite unnecessary and inefficient.

On the same day we were able to observe two more robotic surgeries. The procedures were robotic assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy, and a partial nephrectomy. The unfortunate truth is that having seen these same procedures more than one does start to make the observation less exciting. At this point having already mentioned what the procedures through the earlier blogs I am not going to define the procedures here. However, a few observations I made was that the camera used for internal view often gets smudge on them from the cauterizing, blood, etc. In such cases the camera has to be taken out and removed from the robotic arm and replaced with a different one. In such cases I think it would significantly more important if the camera was self-cleaning or could be cleaned and used again. I have attached here a picture of the resident in action during the robotic laparoscopic prostatectomy, along with the wide array of tools used.

The following day we got to see three more surgeries. The first of which was a cyst urethra extraction – an extraction of a cyst in the urethra. It may be because the patient was a female that the surgeon didn’t have to do the procedure laparoscopically, since anatomically the female urethra is much shorter than that of the male and may be operated on easily. The second one was a transurethral removal of bladder tumor. The procedure was laparoscopic and the tumor was simply removed using a resectoscope. I noted that it would be a bit better if they could adjust the pressure of the irrigation on the scope. Also the bag into which the water that was flowing out of the urethra was collected could have been bigger since there were many instances during which the residual fluid spilled on the floor.

Following that we were able to observer a vesicovaginal fistula repair. The procedure is simply in that the surgeon simply closes the fistula that formed between the bladder and the vaginal tract. It was a bit odd that the surgery had to be delayed by a few hours so that one of the staff could go obtain a special kind of retractor known as the lone star retractor. I have attached a picture of the retractor below. The retractors use is simple such that the tissue may be hooked to a string or cord and latched on the retractor to hold back the tissue.

You really only need one kidney!

Jagan Jimmy Blog

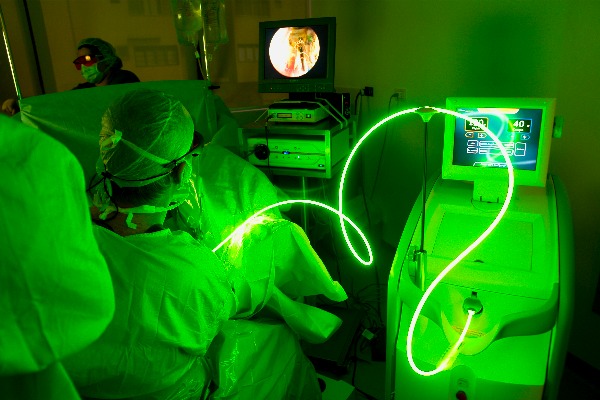

During the first half of the week we were fortunate enough to see a few interesting procedures. The procedures we saw were the vaporization of a prostate tumor, artificial urinary sphincter placement, and a full radical nephrectomy. The vaporization of the prostate tumor was a surprisingly simple procedure. A scope with a laser attached was simply inserted through the urethra and the laser therapy provided by the AMS green light XPS system was focused on the tumorous area. I may include the picture of the procedure if it isn’t too big for the blog to upload (If I can’t upload I will upload an image from online of the laser being used)

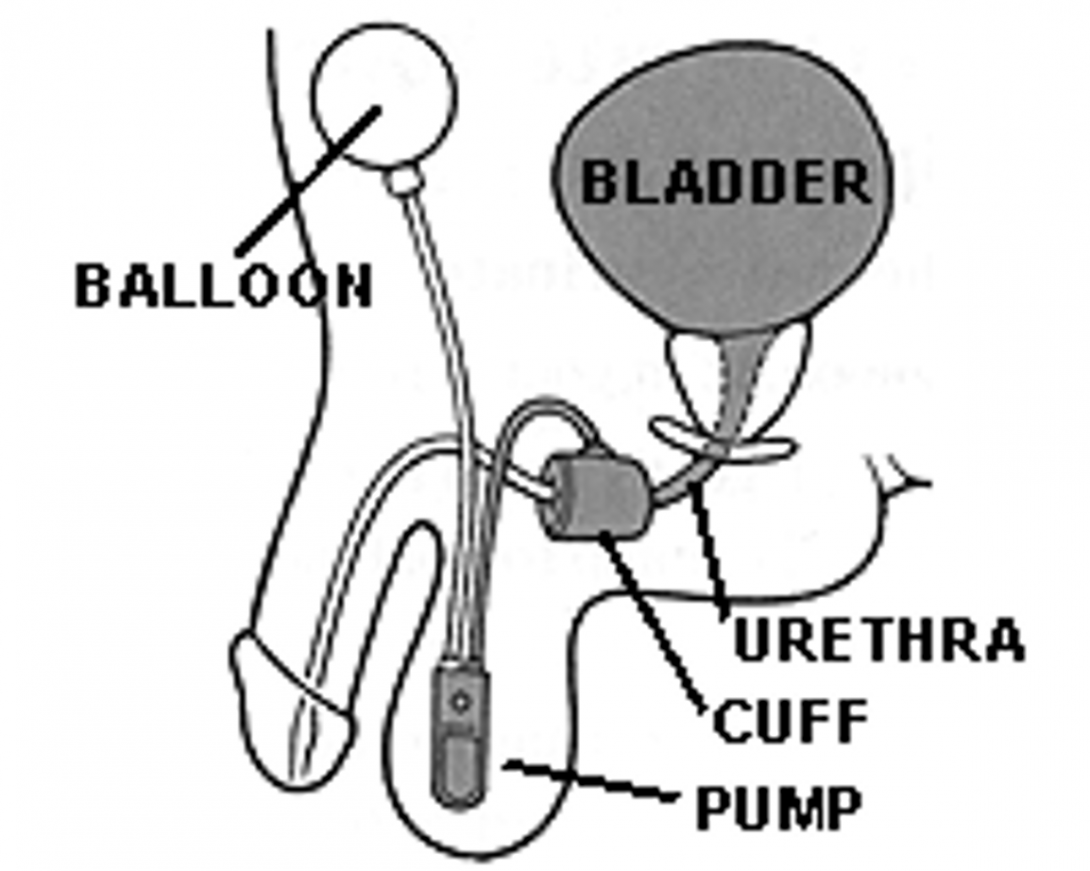

After that we were fortunate enough to see a major portion of the artificial urinary sphincter placement procedure. The urinary sphincter placement was for a patient whom we saw in the clinic last week. It was interesting to understand how simple the functioning of the artificial sphincter was. The artificial sphincter has three components to it: a balloon with a fluid, a pump, and a cleft (see image). The balloon is the pressure regulator and a fluid reservoir. The pump acts to move the liquid back from the cleft to the balloon; and the cleft is what encases the urethra near by the bladder neck. The balloon is placed in the lower abdominal region. The balloon will be adjusted so that the regular pressure abdomen (with an empty bladder) will be sufficient enough to cause the balloon to push the fluid it holds into the cleft. As the fluid moves into the cleft, the cleft inflates and pinches on the urethra thus preventing incontinence. In order to void when the bladder is full, one needs to squeeze the pump repeatedly so that the fluid that inflated the cleft may be pushed back to the balloon, which then loosens the urethra and allows for voiding. Due to a delayed resistor system placed in the pump, the cleft is then automatically re-inflated as the fluid moves from the balloon to the cleft. The procedure is a bit complicated due to the importance of the placement of the components of the artificial sphincter. One of the major downside of the sphincter is the liquid that inflates the cuff or the one that is moved between the balloon and the cleft disappears over time. Which means that they diffuse out of the tube, leading the sphincter to artificial sphincter to fail.

Another procedure that we able to observe was a robot assisted radical nephrectomy. The procedure was different from the other nephrectomies that we previously saw because this was the first full nephrectomy we saw. Once again the patient was one who we saw last week in the clinic. Overall, the set up and such is not any different from the other nephrectomies. Once the patient is brought into the OR they are put under anesthesia, then under the guidance of the attending surgeon the patient is positioned to allow for optimal use of the Da Vince robot. First an incision in the region of operation is made and using a scope the internal position of the organs and such are examined and the surgeon makes the decision as to where to make the additional incisions for the robotic arms. There are certain rules about how far the incisions for the robotic arms should be made for the robotic arm to be able to move around once inside. Once the robotic arms were in place the surgery was started out by the resident surgeon by cauterizing and cutting one tissue at a time. The complicated portion of the surgery was having to clip the major vessels such as the renal artery and the renal veins. During the procedure a thick branch of the renal vein began bleeding, and the surgeon had to quickly cut off the blood supply and clip the ends. However, the surgeon couldn’t do this fast enough because the clip applier could only hold one clip at a time and had to be detached from the arm for the nurse to reload it. Nonetheless, after clipping all the major vessels carrying the various fluids in and out of the left kidney were clipped and cut off, and after all the fascia (connective tissue) around the kidney was detached the kidney was bagged. I personally found the surgeons’ attempt at removing the bagged kidney from abdominal cavity through one of the incision to be quite weird. They literally tried to pull out entire bag through a small incision while stretching out the skin. However, after being unsuccessful they had no other choice but to make the incision larger to get the kidney out. To my surprise the kidney they pulled out was quite large. It was about 7 inches in length and its central portion was as big, if not bigger than, my fist. Also, during the procedure one thing I noticed was that the distance between the console and the patient is far enough that sometimes the surgeon at the console cannot communicate properly to the resident by the patient.

So that pretty much sums up the most exciting things we saw during the first half of the week. Look for the next blog to know more about our visit to urology department’s clinic for private patients, and about my overall thoughts on the first rotation.

Voiding from Urology 🙁

Jagan Jimmy Blog

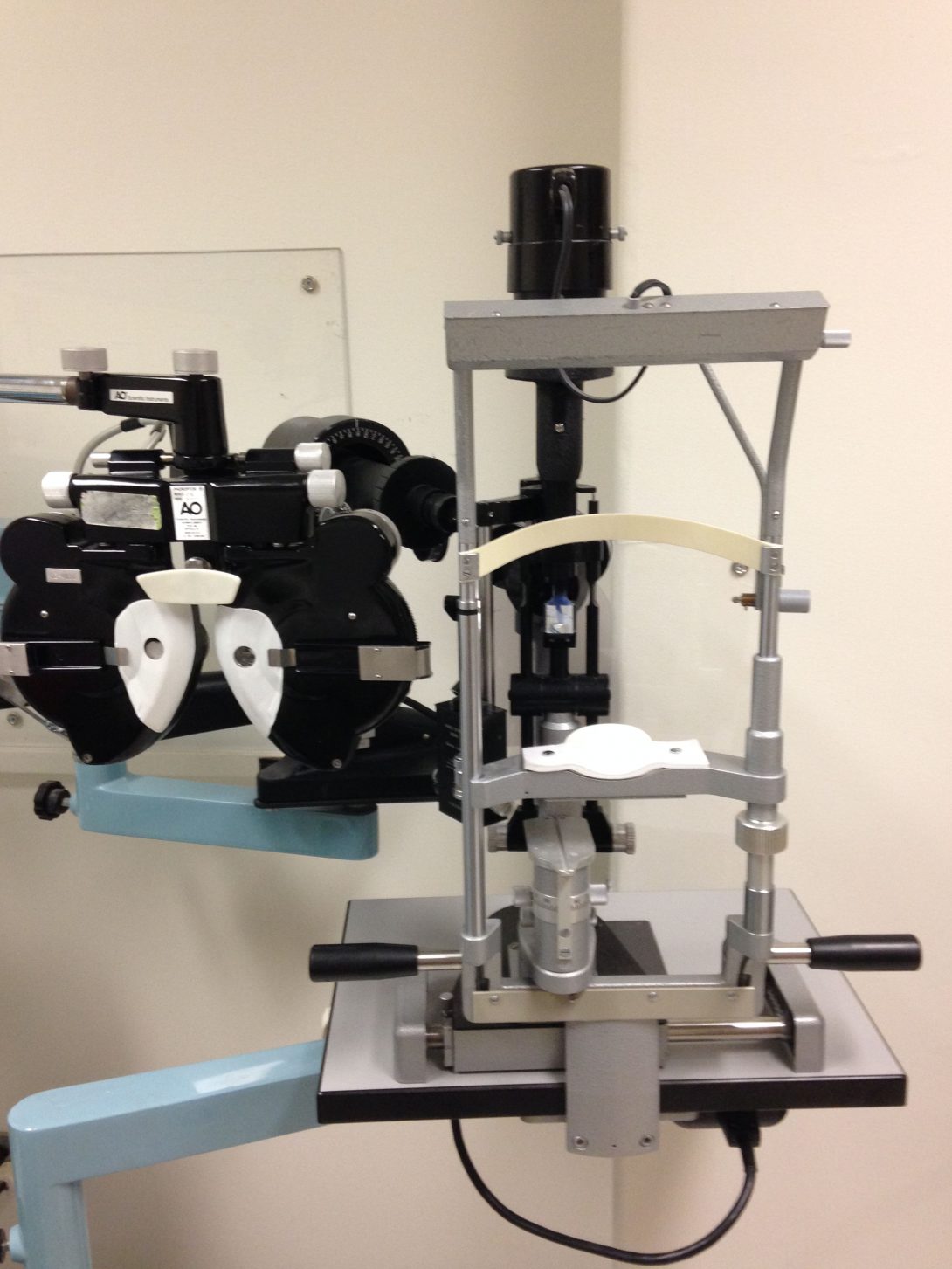

During the second half of the week my rotation partner (Mark) and I were able to visit the University Center for Urology and get a glance at the OR one last time. The University Center for Urology is on the fourteenth floor of the building located at 60 E Delaware Avenue. The clinic is still part of the UI Health system, however it is dedicated exclusively to seeing/serving private patients. From what we saw when we were there, there were only three nurses present at the clinic, and we were told that the clinic only has one attending at a time. While we were there, the attending present was Dr. Ross. As how it was at the other clinic, we were able to observe the two common clinical procedures of performed by urologist: a cystoscopy, and a transrectal prostate biopsy.

The clinic being dedicated to private patients, I had expected the instruments and such of the clinic to be up-to-date with what’s available in the market. However, I couldn’t be any more wrong about making such an assumption. The clinic in fact had instruments that were older and outdated than the ones the outpatient clinic open to the public at the main hospital had. Dr. Ross explained that the clinic doesn’t need the costly newer equipment because the clinic isn’t big enough nor have lot of patients requiring newer equipment. Whereas, the outpatient clinic at the main hospital need newer equipment since more patient is being seen there and the newer models makes procedures a bit easier and faster.

Note that here when I refer to old and new equipment, I am primarily referring to the cystoscope and the prostate biopsy needle gun. The cystoscope at the University Center for Urology is a flexible one however it isn’t high-tech enough to allow to be connected to a monitor and such to display the visual. The user has to look in through the eye-piece at the external end of the cystoscope. Whereas, at the outpatient clinic at the new hospital has cystoscopes by which the user may see the visual enlarged on a monitor. Similarly, the prostate needle biopsy gun used at the former location is a reusable one whereas at the other clinic it is disposable one.

Overall, the environment at the University Center for Urology was quite calming and organized. The patients barely had any waiting time as there weren’t many of them and was never overbooked. Moreover, I think it would do injustice to accounting for our experience at the University Center if I didn’t mention a few words about Dr. Ross. Given the vast experience he has had in the field, he is able to explain thoroughly even the most complicated concepts humbly in simple terms to the patients and students. He is greatly passionate about education and patient care, so that while ensuring the patient’s comfort he also acts as a great teacher by narrating every procedure and encouraging active participation.

Following the clinic we were able to be visit the OR one last time as part of our Urology rotation. During our rotation we say a robot assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. At this point my partner and I have seen more than five prostatectomies by different surgeons over the past three weeks, and it is safe to say that we know the procedure well enough to provide a general narration. Nevertheless, each time we see the surgery there are different specifics we notice and identify. For example this time around we were noticed that for laparoscopic procedure having suction that is flexible at the tip so that it may be angled to reach certain corners. Whether such suction tool exists for as a Da Vinci robot addition is unknown, however such a tool doesn’t exist for manual laparoscopic uses and could be highly useful.

The past three weeks have shown me how wonderful the realms of medicine and engineering are when they coincide. The rotation has provided me with an in-depth exposure to the hospital areas and settings that I wouldn’t have been able to see, otherwise. I have come to realize the importance of innovative and efficient engineering as the needs for the new instruments and concepts are far great in the general discipline of surgery. Hopefully, one day advanced robots or medicine or an even other convenient forms of treatment may be engineered that’s highly effective, yet minimally invasive to improve health of the people. Nonetheless, it is extremely important to acknowledge the great effort put in by the medical students in the rotation, residents, and the attending surgeons who helped us explore the department and shared their thoughts to make the experience a memorable one. Two individuals I would like to thank specifically would be Dr. Tony Nimeh, M.D and Dr Niedenberger. The former for put up with us and making sure that we are getting a wide variety of exposure and helping us out whenever we were lost, and the latter mentioned for taking the initiative to have urology department in the Clinical Immersion program. Thank you Urology for the wonderful three weeks.

Next up, it’s time to explore Hematology/Oncology and Radiation Oncology. I am excited and looking forward to that rotation.

*Note: To the handful of individuals who take the time out of their day to look over at my blog, I am thankful for your time and attention, and am genuinely sorry for not updating some of these posts sooner.

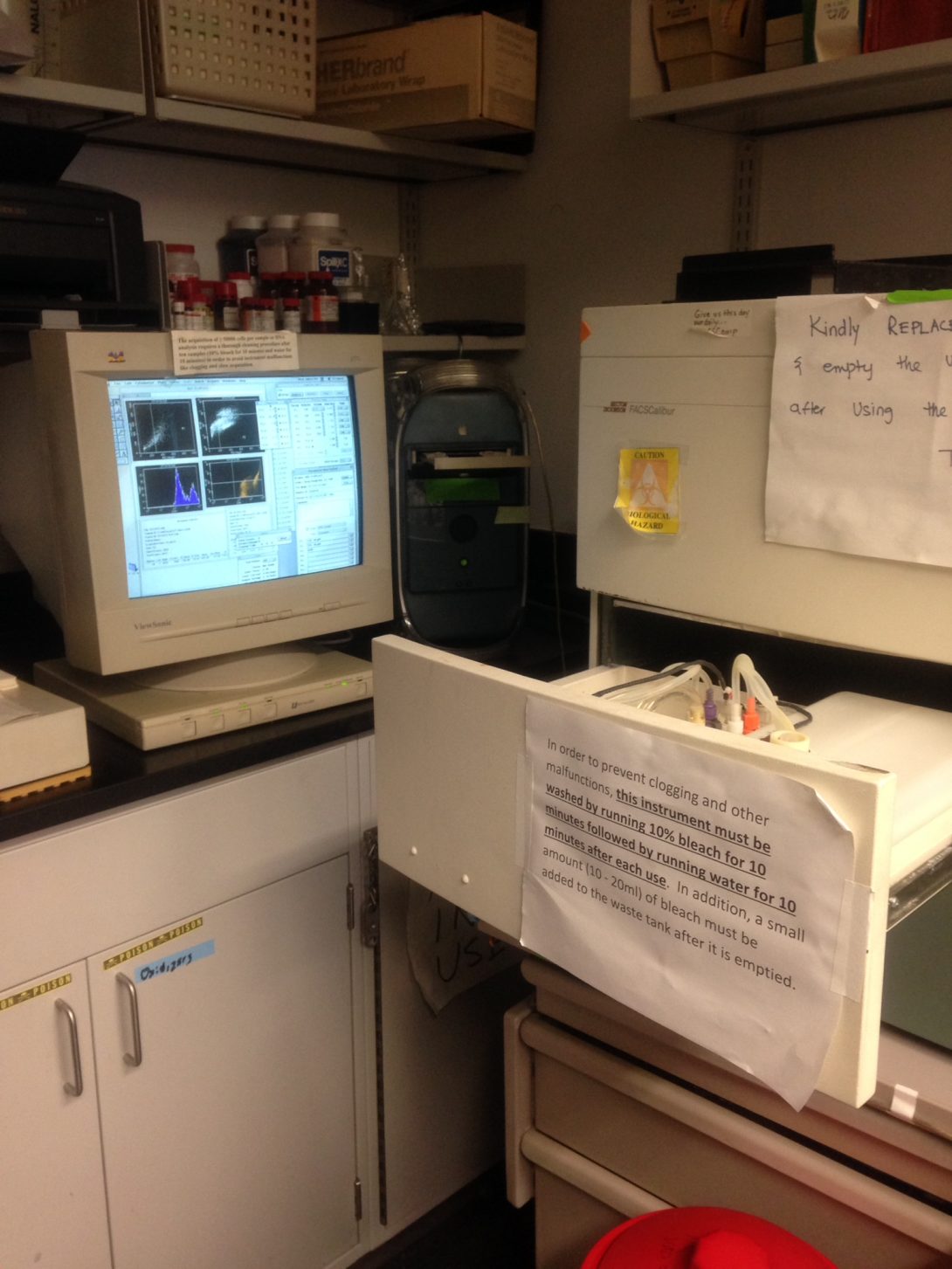

**I have included here a picture of the cart containing the cystoscope that is pushed around from room to room as needed at the University Center for Urology as needed.

Hello Hematology/Oncology

Jagan Jimmy Blog

As we start the fourth week of this wonderful internship, everyone is starting their second rotation in a new department. I had to wrap up my stay at the Urology department and start exploring the Hematology/Oncology department with a new partner. Unfortunately enough, I was unable to come in on Monday and therefore didn’t get to meet the handful of members at the new department along with my partner. Nevertheless over the next two days I was able to meet most of the staff there and attend a few events such as the research lab meeting, see the stem cell lab, and even do inpatient rounds with an attending and the residents.

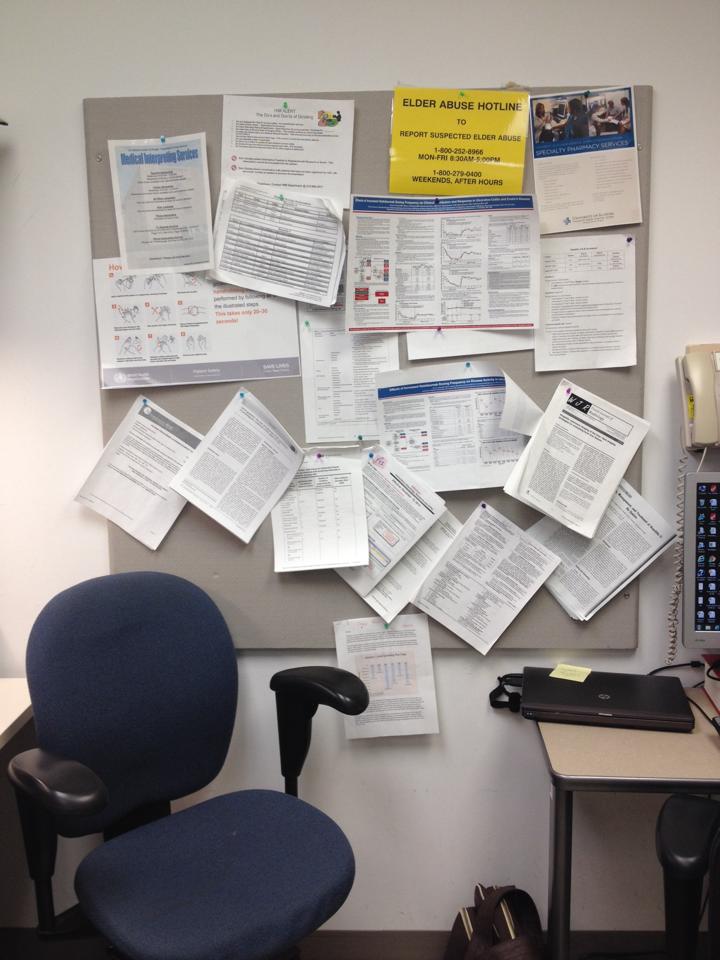

I found the research lab meeting to be interesting, however it wasn’t anything out of the ordinary. The meeting had only eight individuals involved (excluding us two interns). The lab meeting reminded me very much that I am used to having with the members of UIC LPPD. Dr. Rondelli talked to each one of them about their research or about the tasks they ought to complete. He spent the most time discussing with Dr. Patel about edits to the figures for a paper they are writing. I found it interesting that even doctors with years of experience as researchers still have to spend a great deal of time making figures for researchers papers a great deal appealing. Moreover, another major portion of the meeting was a discussion with another member there (whose name I did not catch nor could find on the department’s website). Interestingly enough, the discussion between the researcher and Dr. Rondelli was about which of the research, carried out by the former, to prioritize and pursue. Inevitably, despite how cool a topic maybe what would be appealing the most to the investors and the people who fund the research was heavily considered when determining when deciding which area to further purse.

An interesting characteristic I observed about Dr. Rondelli was that from the way he communicates to his peers he seems to be able to get them to do what he sees fit without having to order or demand them to do so. I suppose it is because he possesses such profound leadership skills, along with other skills, that he was able to reach the position of the department director. Asides from that, nothing out of the ordinary took place during that hour. The meeting took place in an extremely small conference room equipped with a large TV with smartboard tools equipped to it.

After that, my partner and I were able to visit the Stem Cell Lab. The manager of the Lab gave us a brief overview of the various tasks they carried out in the lab. While doing so, she also mentioned that the lab is a clinical lab and not a research lab – meaning that they don’t store or in general deal with stem cells of anything aside from humans. Overall, the lab employs three very friendly technicians. While giving us a tour of the lab, we were also able to get a glimpse at the costly aspect of healthcare. She said the usage of various machines in the lab, and even some of the lab equipment are simply too expensive to be affordable by the patients who the UI health system serves.

Nevertheless, during our visit we were able to observe the cryopreservation process of a patients stem cells. The sample blood collected was centrifuged altogether in a huge centrifuge machine. In order to prevent the bag with the blood from being thrown out of the machine another bag of equal weight with water needed to be placed opposite to the machine. Once the centrifuge process is complete the bag with the blood is taken out, which at this point has various levels of blood content separated. Based on the total amount of sample collected the lab tech has a way of calculating how much of the platelet should be taken out and how much freezing mixture should be added to the sample. Meanwhile, another lab technician also took a sample of the blood and viewed it under the microscope with a blue dye applied on it in order to calculate what percent of the cells are viable. If the cell is dead its membrane becomes weak and allows the dye to perfuse into it, which then shows up as a blue circle under the microscope. The live cells then would appear as non-blue circles under the microscope. Nevertheless, the technician carries out a counting procedure and determines the viability of the sample. The sample is not stored if the viability is not above the standard set in place. Note that at this point some of the steps are time restricted and are carried out by the lab technician very efficiently. Nevertheless, the sample from which the plateles have been removed and freezing mixture added is then place in a container that lowers its temperature to -90oC in a series of steps. This process alone takes about an hour. Then the sample is placed in a large storage “tank” that is kept cool using liquid nitrogen. Note that the boiling temperature of nitrogen in -196oC, thus one can imagine how cold those storage units must be.

I think the lab can greatly benefit from a large timer to monitor their time restricted procedures and a software that could determine the amounts of freezing mixture components for a specific sample could make their technicians work easier and more efficient.

A picture of lab technicians checking for cell viability and adding freezing mixture to the sample is being shown here.

Getting well-rounded with rounds

Jagan Jimmy Blog

The remainder of the first week with the Hematology/Oncology department was even more exciting than the first half. During the second half of the week we primarily went on rounds with the attending and residents, as well shadowed/observed a few physicians at the clinic.

My partner and I were able to do inpatient rounds with Dr. Venepalli in the Oncology section of the department. It honestly was one of the coolest experiences ever. At a fixed time the attending and the residents meet to do rounds; however, prior to meeting up, the residents and the attending seem to have read up quite a bit on the patient status and history, the former seems to have done a more extensive review of the patients. Each resident seemed to be only responsible for a portion of all the patients on the list. Whether the residents split up the patients among themselves or whether they are assigned to them, I do not know. Nevertheless, upon meeting up, the attending, the residents, and us (interns) collectively walked towards the room of the first patient on the list to see. They stop at the entrance of each of the room and the resident who is responsible for the patient begins to debrief. The review the patient demographics, the diagnosis, complications, current state of being, the state of being for the past few days, any new symptoms, their vitals, and even their alertness. Without flaw, they review every health aspect of the patient. Obviously, to memorize such large amount of information can be tricky thus they all seemed to have small pieces of paper, each being dedicated to jotting down notes on one patient so that recalling information while reporting is easier. The attending also takes notes as the residents are reporting patient info, and she often asks the resident what they think about the patients’ current status, what a diagnosis might be for a set of symptoms, etc. Such practice of requiring the patients to do some critical thinking definitely helps them learn more and makes them more competent doctors.

One of the interesting things I noticed was how calm and caring the attending was when interacting with the residents and patients. I suppose this is why medical school look for candidates that are socially well-rounded and able to keep cool.

During the second half of the week we were also able to spend some time in the clinic with Dr. Rondelli and Dr. Patel. We followed Dr. Rondelli almost through every one of his patient. I was shocked by how different the physician-patient interaction was in the department when compared with Urology. The physicians and patients here seemed to know each other well enough given that they have been working together for a long period of time. The interesting part was that as we walk into the room it is evident to tell how the patients are. The ones who are improving their conditions seems are excited and thrilled, whereas the ones who are not feeling as great or is undergoing the chemotherapy seem to be quite saddened and in pain. Nevertheless, the diverse amount of emotions the patients’ exhibit does require the physician to be quite emotionally competent. While in the clinic two specific cases caught my attention. One was that of a young woman undergoing chemotherapy. Dr. Rondelli informed us of the therapy is difficult on her not only physically, but also emotionally as she is not getting the sufficient social and emotional care she needs outside the hospital. Her situation was quite sad such that her siblings aren’t on good terms with her thus the motive for the siblings to even pay any attention to her are monetary reasons. Such a relation was evident in the clinic, as the sister wasn’t actively engaged in talking about the patient’s care and such.

The second case that caught my attention was that of an elderly man who is terminal, however currently feeling quite healthy. The doctor suggested that he can enjoy the good quality of life that he is experiencing currently or that he may enroll in drug trials that may or may not work and that could have side effects. When compared to the other patients he was actively involved in his care such that he didn’t leave the doctor to making all the decisions. Thus, elderly man was excited enough to enroll in the trial with the reasoning that it may do well to more people. I was quite touched by his decision because he was willing to sacrifice the good quality of life so that medicine research and technology may be advanced.

Furthermore, while spending time in the clinic with Dr. Patel one of the biggest thing that caught my attention was the use of the translation device with a patient. I had previously seen the device however never seen it in use. It is almost like a telephone in that the translator who is virtually connected from a different location listens to the physician and translates to the patient. The major downfall of the system is that since the translator is not physically present in the room they aren’t seeing the physician speak and the non-verbal communication taking place. Lacking such physical cues could lead to not translating the physician’s words with the current tone and pitch. Furthermore, another major drawback was that the translator often couldn’t tell the difference when the physician was talking to the patient versus the resident in the room. Thus, in such cases the translator often interrupts by translating the physician-resident conversation. Overall, one can’t say the system is useless, however it definitely is a slow system that could be improved. The system is placed on a wheeling stand and works through an iPad, however given the actual use of the system one may conclude that having such extensive support system is unnecessary. Further inquire revealed the system is set up in such fancy manner because it was originally meant to be used as a video call system.

Too many people are rounding…!

Jagan Jimmy Blog

The second week of rotation in the department was quite exciting, if not more exciting than the first week. This week we got to spend more time in the Hematology unit of the department. Just like last week one of the main thing we were able to do was go on rounds with Dr. Sharaf. This rounding experience was far different from the rounding experience we had in terms of the number of people going on rounds. Aside from us, there were the physician, fellows, residents, medical students, pharmacist, pharmacy resident, pharmacy students, and the dietician. Overall, there was about thirteen people in the group as we went on rounds. One thing I noticed was that the use of hand sanitizer was more prominent in this department than it is in the other ones. Upon further inquiry, the dietician was able to inform us that this is the case because recently they had an incident where the patient in that one entire wing of the hospital all acquired a specific disease – even the patient who weren’t prone to the disease. Thus, in that case the only explanation was that it was a problem on behalf of the staff. The thought that the medical staff giving the patients disease is quite frightening especially in this department. The patients who are in the department already has a severely weak immune system and thus even slightest exposure to something foreign could make them sick. Obviously, such instances of infection spreading isn’t necessarily because people deliberately do not follow direction, but instead its due to instances where someone sticking their head into the patient room to ask a quick question etc. These tiny instance may not seem to be doing much harm, but evidently enough the consequences of these small slipups can be devastating. This made me wonder why they didn’t have a communication system (like a direct intercom to the patient room form the outside) that nurses or doctors could use to communicate with the patient briefly without having to go inside. The dietician also informed us that to ensure infection control protocols were being followed there would often be people (often designated students, or staff) that would lurk around checking if hand hygiene and other procedures were being followed.

While doing rounds I came to appreciate the dietician’s actions about patient privacy. She was generous enough to not go into some rooms collectively with the group. She wanted to give the patient more privacy, thus visited the patient privately after the group left. Also, she was more economically conservative about not going into rooms where the visitors are required to wear a yellow gown. She didn’t want to waste a gown and go in because prior to rounding she had visited them. My partner and I also decided best not to go into room that required yellow gowns in order to minimize the usage of the gowns. Nevertheless, she informed us that the main reason why everyone goes into the room together is because it is inevitably a learning experience. By having everyone be present in the room, problems won’t be overlooked, and problems may be solved on the spot rather than requiring additional consulting.

The usage of the gowns while visiting a lot of the patients was required because many of them were bone marrow transplant candidate and were on immunosuppressant. Given that they are on immunosuppressant, it is important to not expose them to many foreign substances. Thus, it would be a lot better if the ones who were wearing the gown did put it on properly rather than be lazy about it. Also, an interesting thing I noticed was that there was a stethoscope designated to most patients, so that it stays in the room and only comes into contact with the patient. Lastly, one of the things I noticed while on rounds was that often the care given is hindered or delayed by insurance since the doctors are limited to offering the patients care that they are able to afford – having to make such decisions in such a field is quite saddening because I don’t think anyone should have to think twice about saving someone’s life and saving it using the most efficient method available.

Moreover, we were also able to talk with the director of patient care services. Talking to him was quite interesting. He shared his past work experiences with us and told us about how he got to doing what he does today and such. In terms of his role in the department there wasn’t a well-defined/restricted set of activities or responsibilities that he carry out because he is involved in so many things such as addressing patient concerns directly and indirectly and working with the administration about management issues and such.

We were then also able to get another glimpse into the bone marrow transplant meeting. During the meeting the team involved in the unit comes together and discusses each patient they have seen and talks about their status and asks for suggestions about future decisions if needed. We unfortunately had to leave the meeting early to see the processing of an HPC-A collection. This time around I noticed how the collection had to be transferred into a narrower bag from the bag in which it was originally collected because that bag isn’t ideal for centrifuging. In order to avoid wasting time transferring the collection, it would be highly beneficial if the bag in which the collection was collected was the narrow bag. Since the collection bag is part of a kit the manufacturer would have to produce bags in such shape.

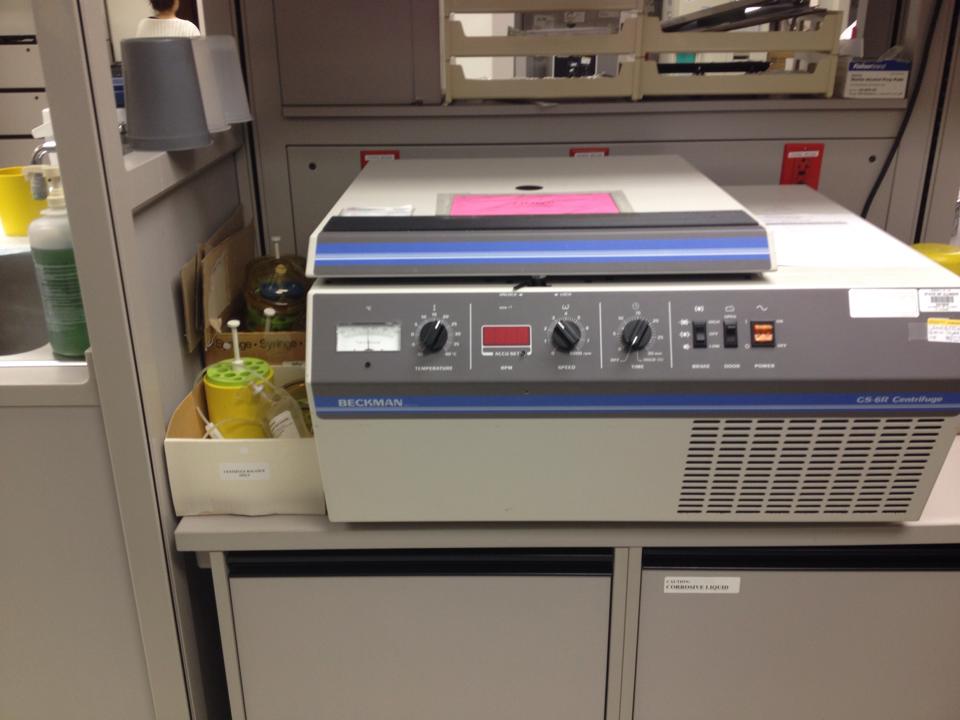

Nevertheless, since it was a larger sample a bigger centrifuge system had to be used, and even that system required placement of a bag of equal weight to that of the collected sample for it to centrifuge properly.

A picture of the centrifuge system is shown here.

The Time I “Malfunctioned”!

Jagan Jimmy Blog

The second half of the second week of the rotation is probably going to be one of those moments I will best remember whenever I recall this internship. Nevertheless, prior to spilling the interesting story here is a brief overview of the other events that my partner and I participated in.

One of the mornings we attended the Lung Tumor board meeting. The meeting had medical students, nurses, physician assistants, and attending and residents from the oncology, and the pulmonary and cardiology departments present there. The meeting took place in a well spacious room. As with the bone marrow meeting, the list of patients dealing with lung tumors that are being treated was by those doctors were discussed and reviewed. Interestingly enough, some of the patients were from the VA. Thus, they had to remotely access the VA server to pull up the images of the patient. The computer was quite slow at the accessing the VA server remotely. The discussion about the patients may have gone by quicker if the computer worked faster.

Moreover, during the meeting something that caught my attention was the concerns and problems one of the physician assistants brought up. She was talking about one of the patient’s primary physician noted a serious tumor however did not directly send the patient to Oncology by getting the patient an appointment that week, but instead the patient only got an appointment a month later. Which brought up the topic of leaving time slots in the physician’s schedule for immediate and emergency cases that need an appointment. They physicians nonetheless become overbooked and are often not able to fit in the new patient into their schedule. Which then raises the question about if they were to prioritize seeing a patient over another one, what standards would be used to determine which patients’ case is more pressing than the other.

Following that, we got the chance to spend some time with the palliative care residents, and got to know about what Palliative care is. They told us how it is a new field and that it wasn’t till recently that UIC got a palliative care department. Nevertheless, the residents shared their reasons to want to go into Palliative care and informed us that because the field itself is only about a decade or so old there aren’t that many programs that offer it and that it is quite a non-competitive field.

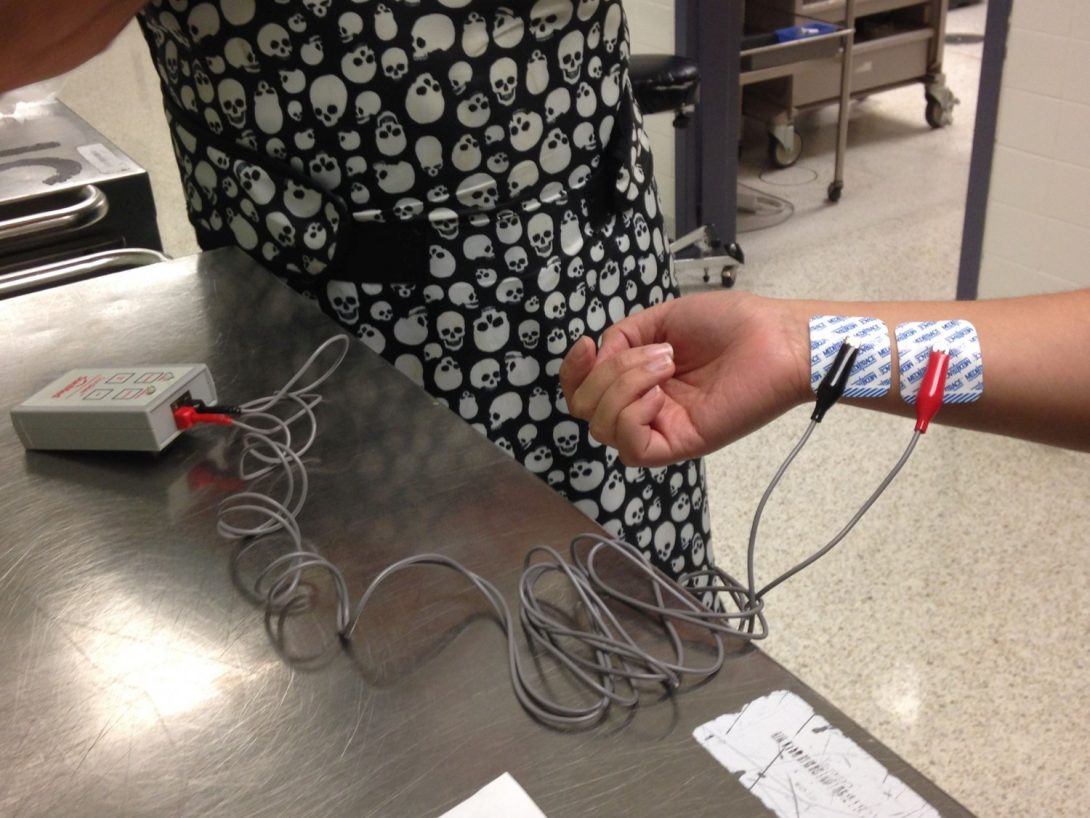

Then later on, we were able to go watch an HPC-A collection. HPC-A collection means hematopoietic progenitor cells apheresis collection. The collection was done by Septia Optia Apheresis system, which was linked directly to the central line. The machine system is able to separate the HPC cells along with some other components of blood from the plasma. The plasma is returned into the patient whereas the remaining is collected.