Students

Mohi Ahmed Heading link

I’m a Senior in Bioengineering that is participating in the Orthopedics and Hematology/Oncology rotations of the Clinical Immersion program. As an athlete and avid sports enthusiast, my future aspirations are to enroll in a Masters program in Bioengineering pursuing the regeneration of cartilage and/or improving joint-replacements procedures with stem-cell based therapies in an attempt to prolong an athletes career as well as apply the same methods to everyday people. The plan with this is to get involved with start-ups focused around this idea. Long-term I’d like to get involved in consulting for a variety of biomedical/bioengineering topics from biomechanics to failure analysis of biomaterials.

Mohi Ahmed Blog Heading link

-

Mohi Ahmed Blog

Go with the Flow [Ortho W1 1/2]

Mohi Ahmed Blog

Summary:

[Covering Tuesday July 5th and Wednesday July 6th; Dr. Marcus is the attending physician]

The immersion program started to the less-than-auspicious information that surgery for our first day had been cancelled. Instead, we would be going on a tour. After observing general facilities we got to explore the lab of Dr. Marie Siemionow–famous for the first near-total face transplant. In her lab we met with two of her PhD students/post-docs that detailed the projects that the lab is pursuing: nerve regeneration and chimera cell transplants. It was reassuring to see this lab uses complex science to solve complex issues with the same skills I learned last semester regarding stem cell and cell culture procedures.

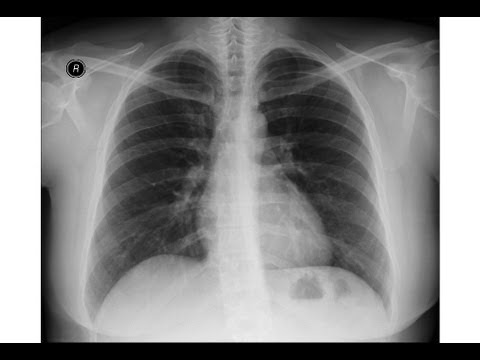

Bright and early, we were treated to a lecture by senior residents and attending physicians on surgeries and images (x-ray, MRI, MRA, etc.) for residents to analyze and diagnose. Later, Dr. Mejia gave a lecture on hand surgeries with pictures

full of goregalore. The most startling part of this morning class was that different physicians had different opinions on how to handle a given scenario. What one surgeon considered the safest approach to a solution was someone else’s last resort. This whole time I thought that there was an overwhelming consensus on what procedure to carry out for all scenarios, but I now see just how unique certain situations can be and why surgeons would be conflicted on what procedure to carry out.Finally we got to observe the clinic at full speed. Essentially your typical doctor visit, but looking in from the other side (the clinicians perspective). It turns out there’s long wait times on both ends!–more on that later.

Notable Observations:

- Residents can spend 30 minutes or more simply waiting in the hallway for patients to arrive.

- Dr. Marcus needs to work around procedures and surgeries performed by previous surgeons for a given patient.

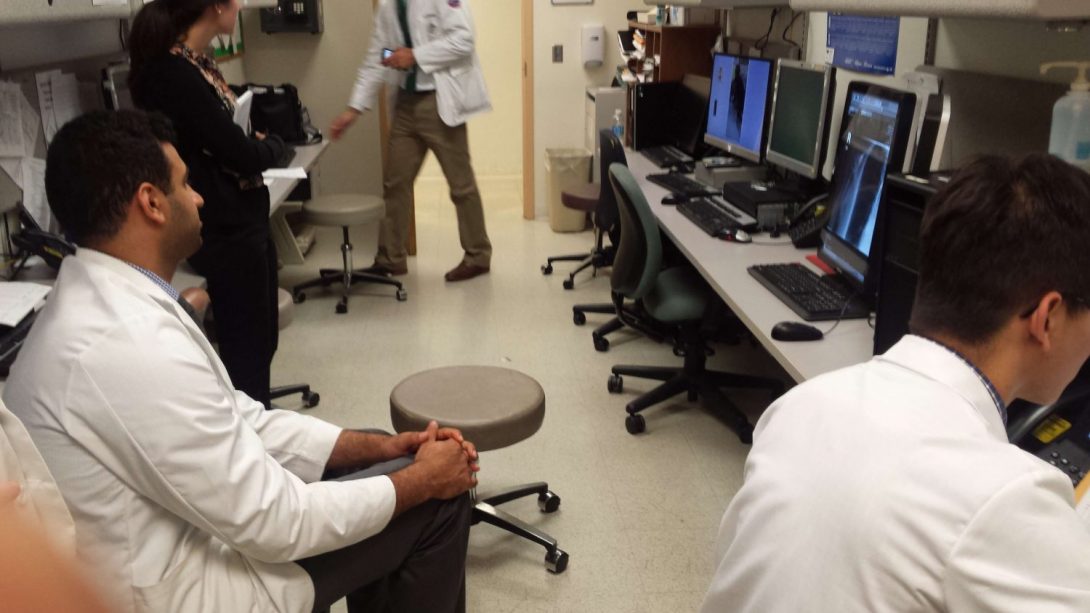

- There is a narrow room with computers on both sides full of residents and attending physicians that I have dubbed “Homebase” as this room is where every member of the clinic reports to multiple times for a given patient visit.

- Plenty of times throughout the day, residents, technicians, and nurses report to Homebase and simply wait for the attending physician because he is with a patient in a room.

- A medical student, resident, and Dr. Marcus all perform the same tests on a patient meaning they are visited ~ 3 times before any real progress has been made.

- The room goes dead silent when an x-ray or MRI is being observed by Dr. Marcus as everyone is awaiting his explanation and diagnosis.

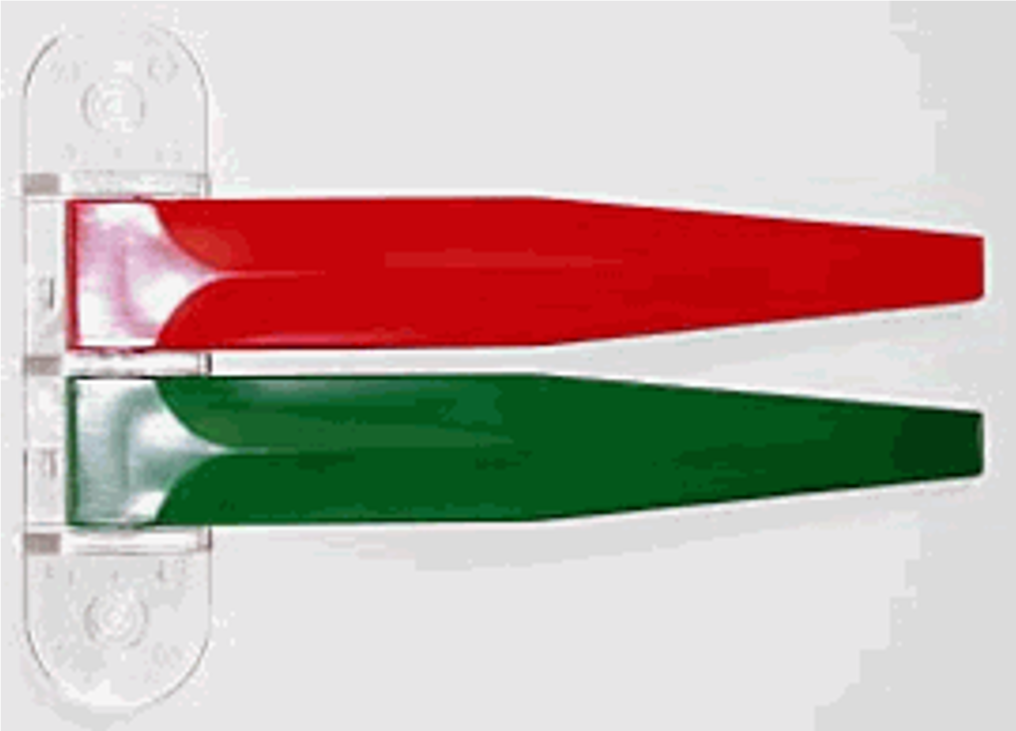

- Red and Green flags are at each patient room to signal whether a patient has not been seen, is waiting on paperwork/files/braces, or has been/is currently being seen.

- Typical game plan for a patient is rehab/therapy –> steroid injections (inflammation and pain) –> surgery. [Stopping wherever problem is solved]

- After meeting a patient and determining the need for an X-ray, residents must file for an x-ray before a patient makes it to the front desk asking about their x-ray.

- Residents carry out dictation, a process where the resident orally summarizes the patient visit over the phone to a transcriber that types up the dictation and sends back to the resident for logging.

Thoughts:

Due to the lack of surgery experience, we have been limited to observing the clinic. It is either a blessing or a curse that our entire focus as such has been improving workflow. At first I wanted to address how a medical student, resident, and the attending physician all assess the patient in the same way before a diagnosis is given. However, I realized this is a hands-on learning opportunity that probably should not be imposed upon.

I noticed that everyone likes to view x-rays on a certain monitor in the middle of the already crowded and cramped “Homebase.” I again realized that although maybe not intentional, this allows mostly everyone to see an image that the attending physician is examining and explaining to residents–again it becomes a learning experience. My only thought here would be to optionally “Teamview” the image to all other monitors instead of having residents huddled around a central set of monitors.

Dictation is carried out in “Homebase” as well, and this area can get very noisy. Dictation itself is already very fast and hard to understand for the transcriber, but additional noise I imagine only makes it worse. Perhaps dictation could be carried out somewhere else?

I think a solution I could focus on is a means for residents and technicians to know where the attending physician is essentially at all times (in a more eloquent way than simply putting a bell on them).

A more in-depth look at improving workflow will take place in the second half of this week’s post.

The Wave [Ortho W1 2/2]

Mohi Ahmed Blog

[This covers July, 7th, and 8th; Dr. Mejia and Dr. Goldberg were the attending physicians]

Summary:

We finally got a chance to see the clinic part of the work week run by other physicians and compare the differences between them. Surprisingly, there was not actually much of a difference. Under Dr. Mejia however we were introduced to a new workflow concept he had been attempting called “Wave Scheduling.” We learned that there are a few main types of patients: follow-ups, post-operations, new patient, and workers compensation. Essentially they range from brief conversations with the attending physician up to hour-long interactions with multiple procedures. Wave scheduling is the act of scheduling multiple follow-ups together around the same time, followed by one or two appointments of the longer variety. The result is the ability to see ~6 patients per hour and a pulsating flow of activity in the hospital; Dr. Mejia will be running around the clinic for a burst of time and then have ~10 minutes to stop and tend to other things before the next wave of patients come in. Apparently, other attending physicians are not fond of adapting this new style of scheduling. Thanks to Dr. Mejia, we also met with Jonathan Bode who is more or less in charge of scheduling and workflow in the hospital–among other things. He too was able to provide us various insights from a more administrative end of hospital operations. Lastly, we saw the stark similarities between how the hospital appears to run under either physician. I personally got to see a dislocated finger get put back in place with the help of x-rays and a cast being applied. I also got to see the administration of a numbing agent (commonly called a “Popper”) followed by the administration of a steroid injection to reduce pain in the hand of a post-op.

Notable Observations:

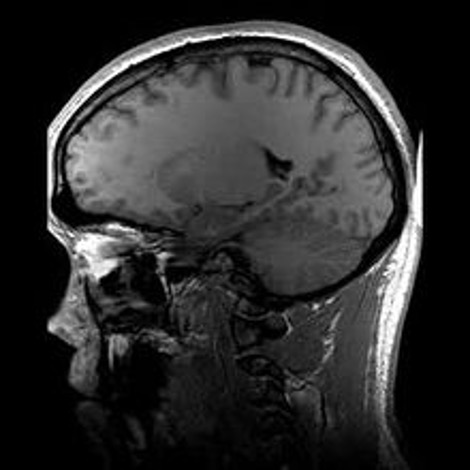

- A patient had an MRI that clearly showed a herniation and the attending physician recommended an injection, but the ER physician that addressed this patient determined that it would be ineffective and refused administering the injection. The attending physician at our hospital took another look at the MRI and saw again that there was clearly a herniation and could not figure out why the ER physician refused to administer the injection he recommended.

- For Spanish-speaking patients, the sole Spanish-speaking resident is assigned to handle the patient for obvious reasons until Dr. Mejia can himself.

- On a given day there could be twice as many residents as patients and also the opposite–we saw both occur in this week alone.

- There was no available face mask in a room when a patient requested one as they did not want to spread the common cold they were currently afflicted with.

- Dr. Mejia has to ask which resident saw to a certain patient.

- Stack of papers for Dr. Mejia to sign are left on his desk, unbeknownst to him, until he inevitably returns to his desk.

- For casting, the fiberglass with impregnated resin simply requires water to activate. However, it leaves a sticky residue on the gloves of whoever is administering the cast and requires them to be very careful where they put their hands unless they swap gloves.

- According to Jonathan, there is a need for a same-name signifier as two patients with the same name administered at the same time is not entirely uncommon.

- If a patient comes in having needed x-rays and this is not discovered until a resident talks to them and then gets sent to get x-rays, that patient has taken up a room for over an hour that could have gone to someone else if they had just been sent to get x-rays from the beginning.

- Dr. Mejia personally numbers doors with magnets to adhere to his wave schedule–if he messes up, the entirely system crashes until the next wave starts and he can reset the order.

- Jonathan has a team dedicated to to studying the time it takes for patients to come in and out of the hospital taking into consideration the attending physician and their specific patient classification.

Thoughts:

If the front desk has access to the records of an incoming patients, they should be able to determine if the patient has x-rays in the system or needs them so that they can be sent to get x-rays first before unnecessarily taking up a patient room.

There has to be a better way for Dr. Mejia and his wave schedule to avoid him personally having to change numbers on doors.As a team, we will look into this and plan on scheduling an outside meeting with him to pitch the schedule. Our solution should go hand-in-hand with the research study the Hospital Improvement Team plans on carrying out.

Perhaps a different resin can be impregnated into the fiberglass casts such that they do not leave a sticky residue on latex gloves. Latex gloves are cheap, but this impact could add up over the years to save money long-term.

I eagerly await Week 2 where we finally will observe surgery and see if we can notice anything notable there.

Slow it Down & Look Outside [Ortho W2 1/2]

Mohi Ahmed Blog

[This post covers July 11 and 12; Dr. Chmell and Dr. Gonzalez were the attending physicians]

Summary:

This week started off with Dr. Chmell in clinic where 1/3 of his patients did not show. This resulted in a relatively relaxed day for basically everyone. Dr. Chmell explained to us that an understated issue in Orthopedics is that certain people have an allergic response–usually delayed inflammation–to metals such as the one’s used in implants. A test to detect this allergic prior to operations has not come into full fruition though a few have tried. This issue occurs for a small percentage of people, but that does not mean it is a hurdle that can be overlooked.

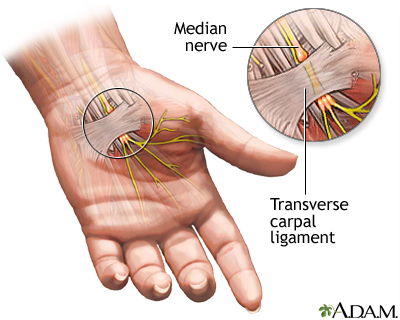

The next day was our first visit to the scenic Illinois Bone and Joint Institute (IBJI) with Dr. Gonzalez attending. Compared to the normal University of Illinois Hospital clinic, this was a completely different experience. Essentially, all patients were post-ops (patients checking in their progress after undergoing a procedure recently) and there were not many patients in general to be seen. This resulted in an extremely auspicious circumstance where Dr. Gonzalez had time to give us two lectures on the human hands from an anatomy/surgery standpoint and also an engineering (biomechanics) standpoint. Furthermore, in between patients he even had time to intermittently educate us on small details in the field, his experiences, and advice, Overall, without the rush of a high volume clinic, both Dr. Gonzalez and his resident had time to spare in being more attentive and social with patients.

The view was worth the wait anyway.

Notable Observations:

- With a lower than anticipated volume of patients, residents are left with basically nothing productive to do for more than an hour.

- Very few hand sanitizers in the IBJI clinic relative to the University of Illinois clinic.

- The IBJI clinic has more sophisticated flag system (includes room order like Dr. Mejia’s magnets and also includes whether or not an injection or x-ray is needed). However, this system is rarely used in a sophisticated manner, the flags correspond to the order patients came in–not their classification (post-op, follow-up, workers compensation, or new patient).

- There is only one resident at IBJI compared to ~9 at University of Illinois Hospital depending on the day.

- Where special cases arise, Dr. Gonzalez uses is experience to make a call on how to go about modifying an implant to meet the new needs of the given special case. There is not an objective analysis that an be done in a timely manner; Dr. Gonzalez creates a model of the unique region he is attempting to implant into and decides how much to modify the dimensions and angles within an implant to accommodate the special case.

Thoughts:

It is my guess that there is less hand sanitizer at IBJI because it only really needs to be in one place and can still be efficiently used before and after seeing a patient whereas at the University of Illinois clinic this would be impractical as too many residents would be in need at the same time. This must be an advantage of a low volume clinic.

Again, the low volume of patients at IBJI is likely the reason the advanced flag system used is not fully implemented as there simply is not a need for it at IBJI whereas there might be a need at the University of Illinois Chicago clinic.

I noticed a dramatic difference in patient enthusiasm and response in at the IBJI vs what I have seen at the University of Illinois Hospital. This could potentially be due to the nature of appointments at IBJI compared to those at the high volume University of Illinois clinic–to confirm this I will need to compare it to the clinic run by Dr. Gonzalez tomorrow at the University of Illinois. The aforementioned low volume likely is the reason the attending physician could spend more time with a patient in a non-rushed manner and this is probablywhy patients seemed more upbeat. However, I would like to stress again it also very well could be due to the nature of their appointments as opposed to those at the other clinic and is very unlikely due to be dependent on the residents and attending physicians themselves. Again, this will be made apparent in tomorrow clinic with Dr. Gonzalez as the attending physician with an expected 60-70 patients scheduled.

Not sure if Surgeon or Very Specialized Engineer… [Ortho W2 2/2]

Mohi Ahmed Blog

[The following is about July 13th and 14th; Dr. Gonzalez and Dr. Marcus were the attending physicians, and Dr. Gonzalez was the surgeon on the 14th]

Summary:

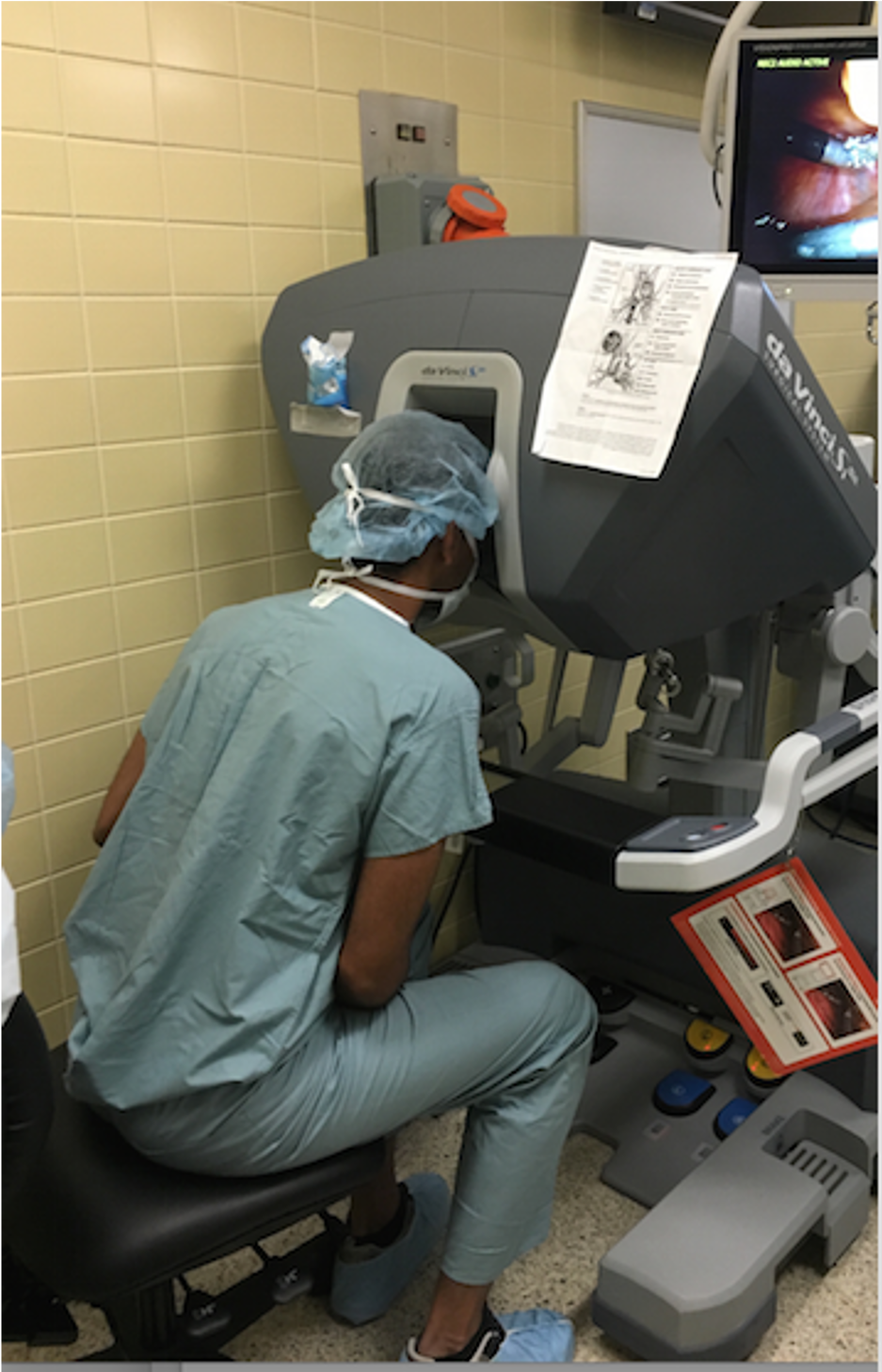

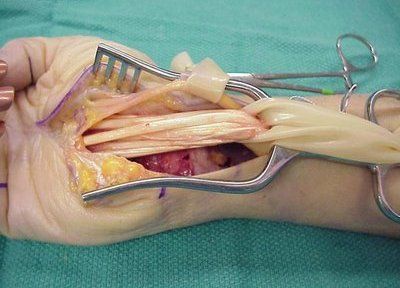

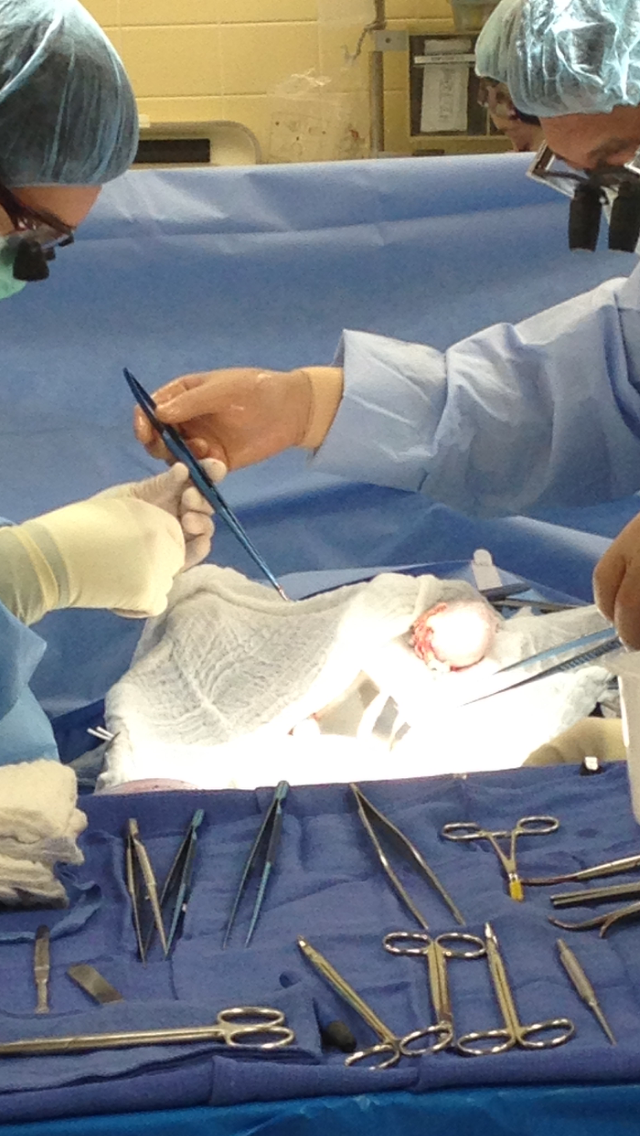

We officially cycled through all attending physicians in clinic. This may or may not actually be true, but it seems that residents are not as lost when looking for Dr. Marcus or Dr. Mejia. This is simply an observation and may only be true on a given day and not generally true. It is at this point we have generally seen what weeks are typically like in clinic for the residents and attending physicians. We finally got to see surgery and wow was this a completely different experience. We started off by seeing a cyst get removed from a wrist which was a rather quick surgery. This was followed by a knee implant revision which was rather long (several hours) and then two knee replacements (arthroplasty). The last scheduled procedure was a hip replacement, but Dr. Gonzalez said it would be a long night if we stuck around for this and recommended we go home as it was already past our official “end” time. To briefly summarize my thoughts on surgery, and intended solely as a compliment, there is a point during fitting, adjusting, and installing knee replacements/revisions where it appears Dr. Gonzalez is not even a surgeon anymore, but rather an incredibly specialized engineer. It is as if he is just building a joint and installing it into a machine.

Notable Observations:

- Name tags on rooms are swapped out every morning depending on who attending physician is–for physicians such as Dr. Marcus this means the rooms he uses change a lot to the point that he has a special set of rooms he likes to use when he can to stay away from clutter and traffic.

- Suture removal is not worth numbing and pain depends on where sutures we embedded.

- There are times where there are a lot of residents waiting for patients, but everyone is still behind schedule.

- Residents do dictation every 3 to 4 patients. If done more frequently than that they are not seeing as many patients as they should; if done less frequently than that they do not remember the patient well.

- Special printer needed for printing prescriptions because of special paper.

- During surgery, the table the limb is on can move when bumped during sudden motions and can interfere with delicate operations.

- Metal prong/spoon to hold skin back must be held by someone.

- Extensive procedure undergone by those who “scrub in” to work very closely during surgery including lengthy sanitation prep and more materials worn to avoid spread of disease.

- During surgeries involving the knees, residents spent a lot of time just holding the leg up and moving it around for whoever is actually operating.

- Tools covered in blood slip out of hands during surgery.

- Delayed plate arrival seriously interfered with surgery.

- Rare, but still happens: gloves are hard to get onto the recently sterilized Dr. Gonzalez even with assistance.

- Relaxing music playing in the background during operations.

- During knee implant revision, cement used to put implant in must literally be hammered/chiseled out.

- Operation table cannot go as low as operating personnel would prefer–eventually end up using stepping stools.

- Sales representative from company that manufacturers implants is present to tell Dr. Gonzalez how to combine pieces to get what he wants and everything he needs to know about every component.

- A lot of guess and check for fitting knee implant in before making a final choice and permanently implanting.

- Dr. Gonzalez mixes cement to implant knee–someone else mixes a second batch as a reference for time until the cement dries.

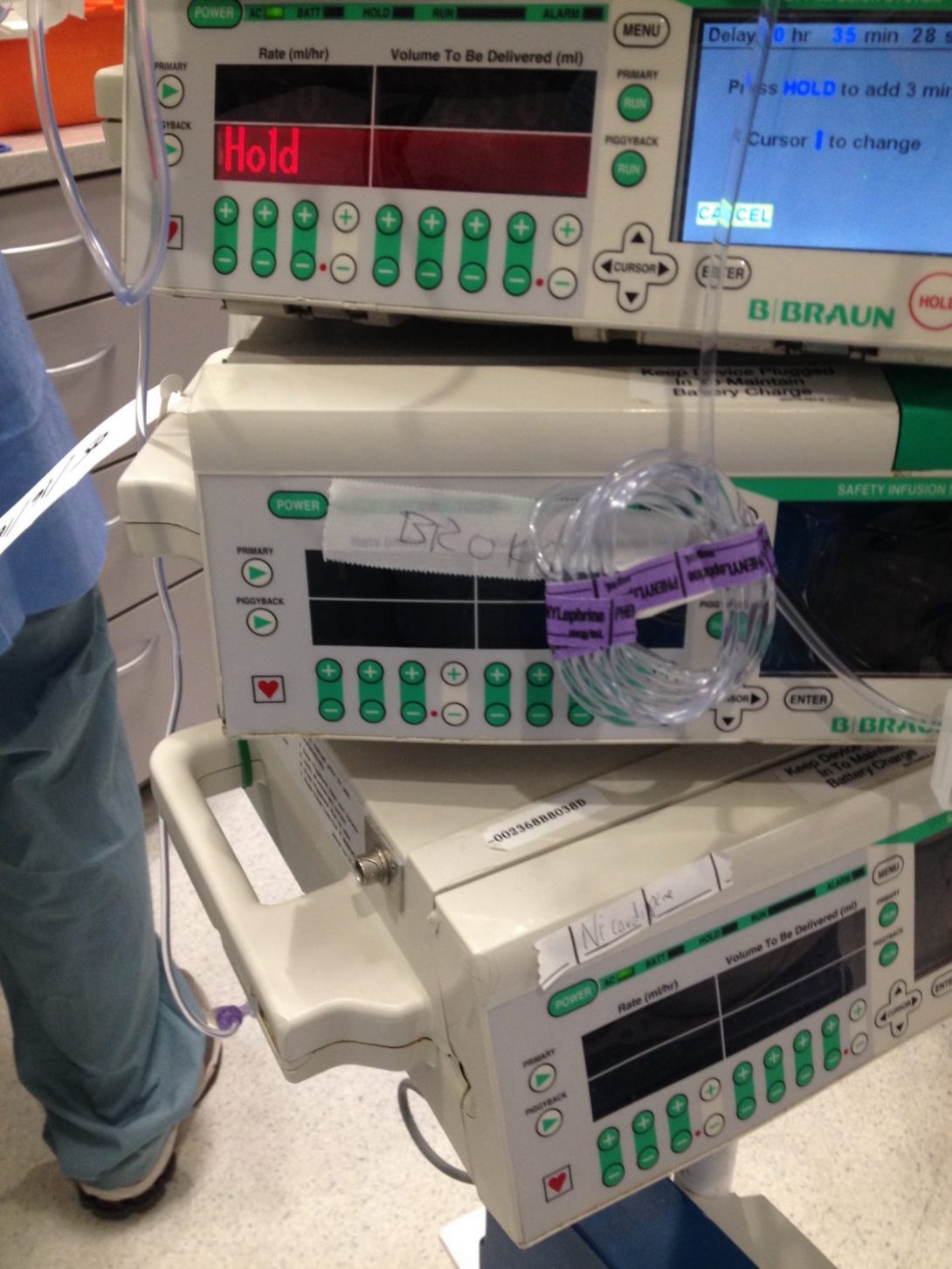

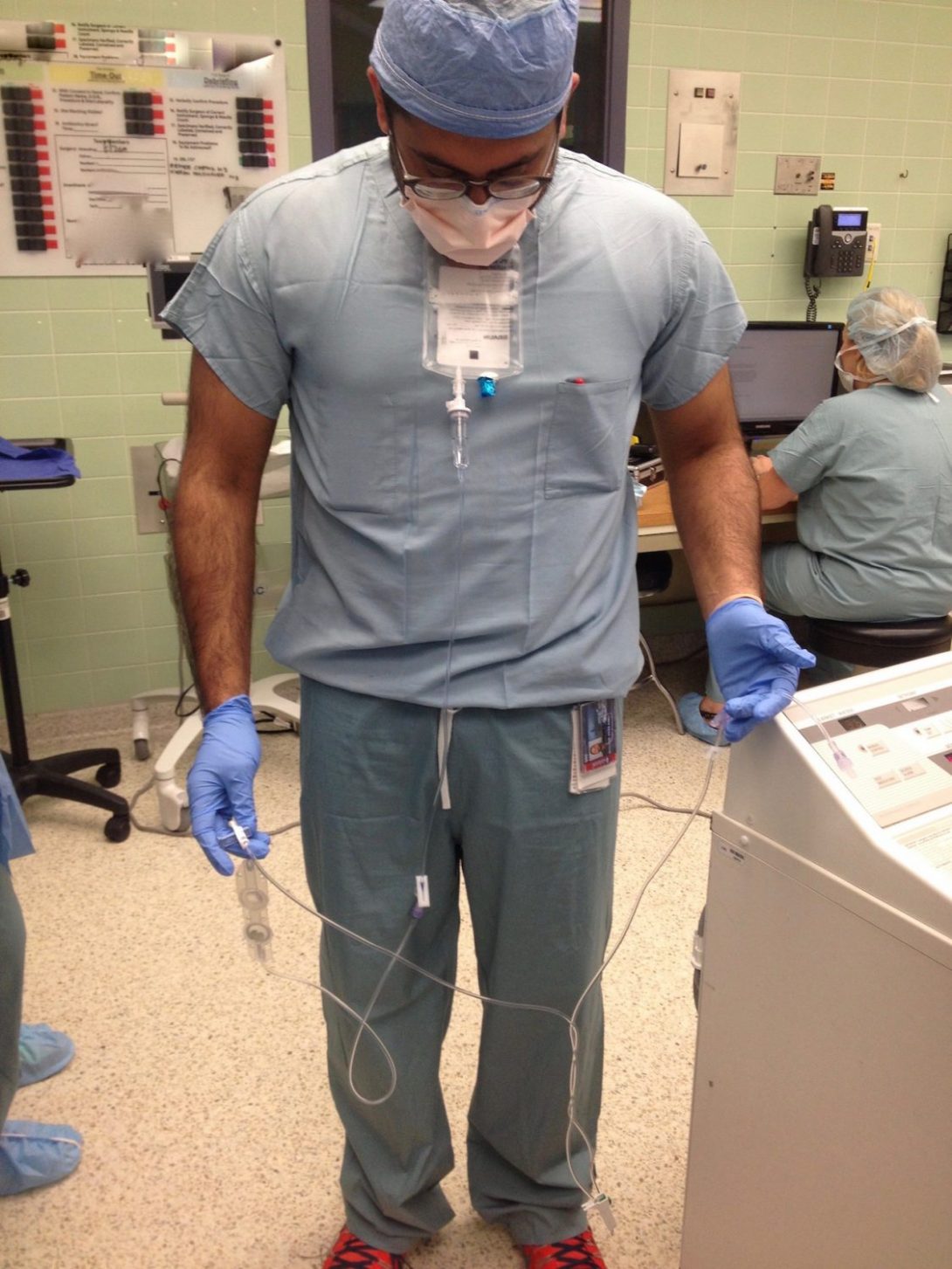

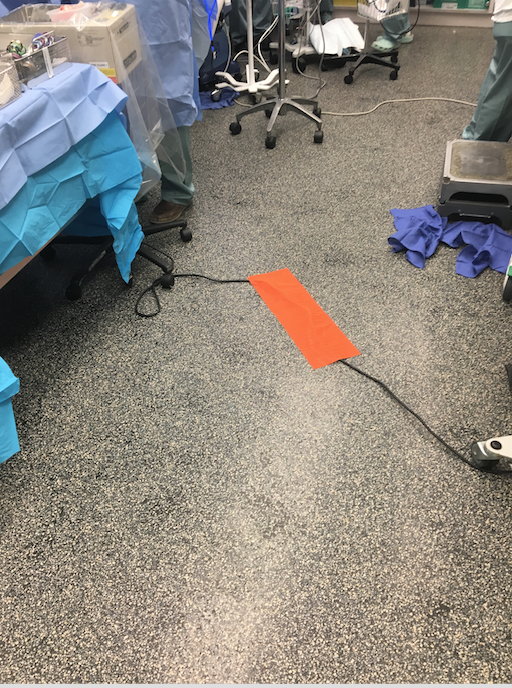

- Extra IV drip bag used to hold cords up so nurses can walk under safely when cover is not available for them to placed on the ground.

Thoughts:

Perhaps a system can be in place where cords connect from their respective machines and then run along the ceiling (or say a hook hanging from ceiling 6.5 ft from ground) to the wall where they plug in that way they could be walked under but still reached–this assumes most of the machines do not need to be moved in and out of the room a lot.

I think Dr. Gonzalez’s work would be made easier on knee revisions if he had a compound that would liquefy/dissolve the cement of the previous operation so the cement could be sucked up instead of taking up time being slowly chipped away.

Perhaps a brace or locking mechanism could hold a patient legs in place temporarily instead of having a resident hold a leg for hours. This would have to be easily disengaged to move the leg around as needed.

Maybe tools could have a revised handle/holding point design to make it easier to hold when covered in blood. The metal prongs/spoons used to hold skin/muscle back could have a means of being secured to the table so that more hands are free and arms are not in the way of those operating.

I eagerly await the next and final day of surgery and hopefully I can I see a hip replacement like I wanted to. Surgery has definitely been the highlight of this experience thus far.

Winding Down [Ortho W3 1/2]

Mohi Ahmed Blog

[This post covers July 15, 18, and 19; Dr. Gonzalez was the attending physician]

Summary:

The orthopedic rotation is winding down. UIH (University of Illinois Hospital) clinic is getting very routine. Obviously the cases very, but it generally is composed of the same observations. We have begun work on our presentation and report about our observation, what we have learned, and what we think could be done. We also attended the Illinois Bone and Joint Institute (IBJI) for the last time and had a busier day than the last week. The patient volume was slightly increased, but the mood was still very relaxed relative to UIH clinic. I especially am excited about our final day observing surgeries as many different types are scheduled and this will be my last chance to see these procedures unless I am on the receiving end of it.

Interesting Thoughts:

- x rays are at one clinic, but not the other for a certain patient and must be sent over.

- x ray at IBJI has security feature that locks screen if a resident/technician/attending is not near.

- Dr. Gonzalez has patients call him to touch base with how they are doing.

- Cyst can only be removed when full, if drained must return before surgical removal–procedure is quick and takes a few days to heal.

- Cyst fluid can be thick and is difficult to remove, bone starts growing as well which needs to be shaved to prevent it from coming back. However, patient can refuse this and opt for repeated draining.

- Resident writes additional notes on each patient’s file and carries them with throughout the day until they can be transcribed via dictation (audio recording of patient interaction and details of diagnosis).

- For severe osteoarthritis, a certain amount of steroids can be used, but cannot exceed use in a given timeline. The alternative at this point is an injection of what is essentially synthetic synovial fluid into the joint.

- There are multiple injection sites in the knee.

Thoughts:

Up until now I did not even consider the existence of synthetic synovial fluid. Apparently the injection is very general, essentially all of a given dosage is injected into a joint. There is really nothing precise about it, but perhaps it does not need to be. It’s as simple as entering an appropriate location into the joint and dispensing the fluid.

Most of these days were routine so my final thought is an afterthought on Dr. Gonzalez following up with a patient via phone call. With insight from Dr. Chmell, our group thought of designing an app as a means of patients being able to easily interact with their doctors. The idea would be for post-op patients to get the app and essentially update their doctor and milestones they have achieved since surgery to determine if they are on track. The idea would be to eliminate unnecessary appointments that only involve 30 seconds of interaction to say something along the lines of “everything looks great, see you in 6 months.” Also it would provide doctors with data on how long after surgeries patients are achieving certain milestones such as walking again, climbing stairs, etc. This way, doctors know if a patient should come in sooner because they are not progressing as fast they should. This could help patients come in sooner rather than later if something is wrong.

I eagerly await my final day observing surgery–there is a lot of hand procedures scheduled along with hip procedures. I will be getting a great mix and be able to compare the similarities and differences of procedures to different areas of the body.

The End of Ortho, But There’s Still More To Do [Ortho W3 2/2]

Mohi Ahmed Blog

[This post covers the last few days of my orthopedics rotation; Dr. Gonzalez and Dr. Goldberg were the attending]

Summary:

We experienced a couple more hectic days in clinic at the University of Illinois Hospital (UIH) followed by our last day in the OR with a plethora of surgeries lined up: anterior and posterior hip arthroplasty, endoscopic carpal tunnel release, knee fusion, and several other hand surgeries. Overall in clinic I saw most of the same, delays for everyone caused by little nuisances that added up. Specifically, the clinic was backed up for at least an hour because 4 consecutive patients had to be sent to x-ray–and that was for just one resident, let alone the other patients from other residents. Getting sent to get x rays continues to clog up patient flow and is what many residents told me they’d like to get resolved. In only my 2nd and last time in the OR for orthopedics I saw multiple compensations that were not present the first time–more on this later. Clearly, there’s still more to see.

Interesting Observations:

- several patients had waited weeks after their initial injury and had made their situations much worse because of it–the afflicted area had healed improperly.

- A hip replacement where the patient was already able to comfortably walk and around and even dance just 4 weeks post surgery.

- Implants for surgery arrived well before start, but the company representative was not available and therefore surgery could not start on time–no point in equipment being there if it cannot be used by company rep.

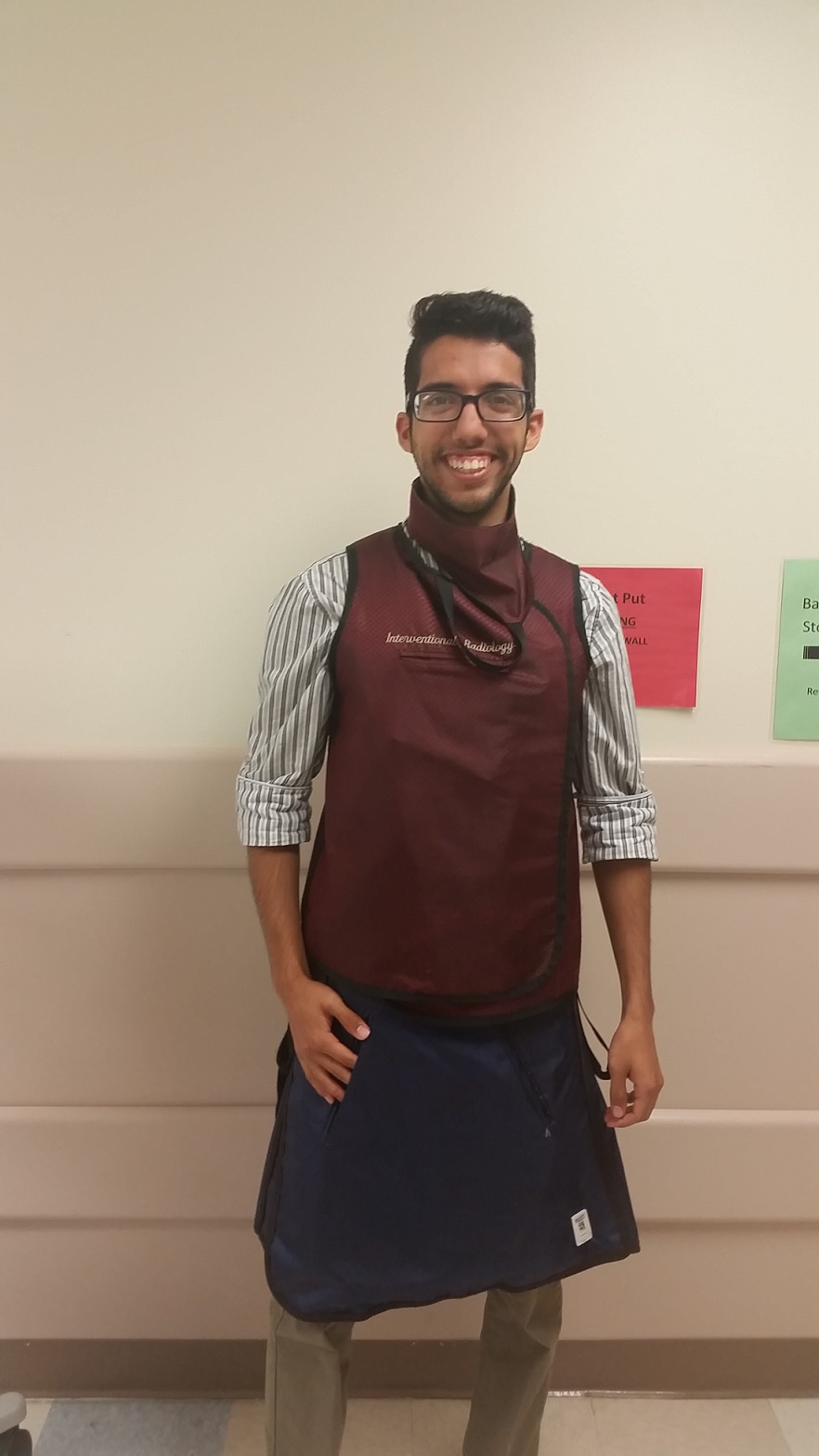

- Lead vests and neck covers (for protection from radiation) are simply placed on a couple of racks throughout hallways. Lead vests can be taken at will, many neck covers missing.

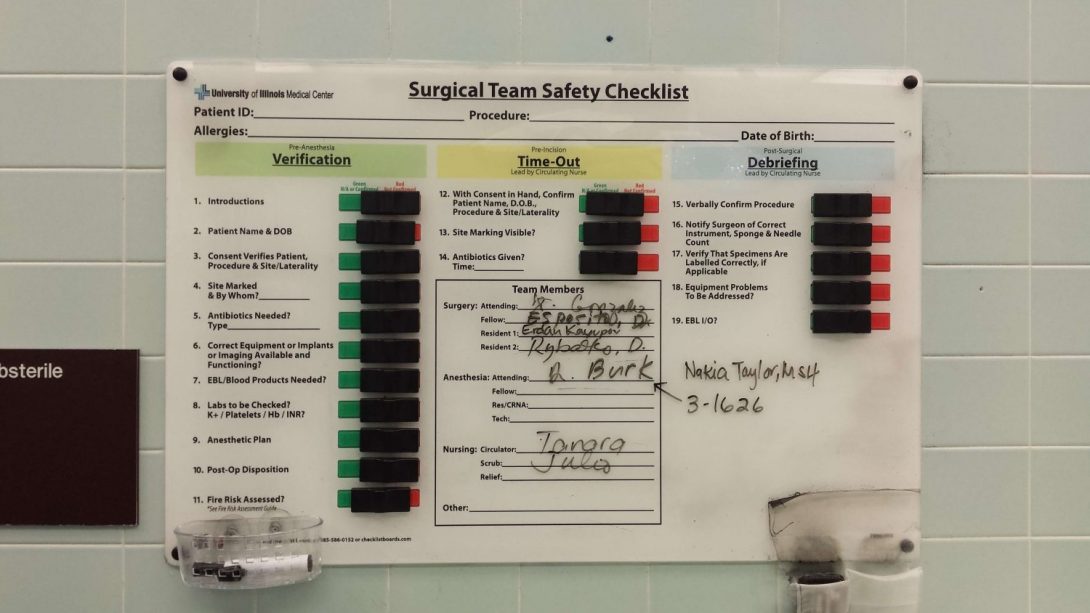

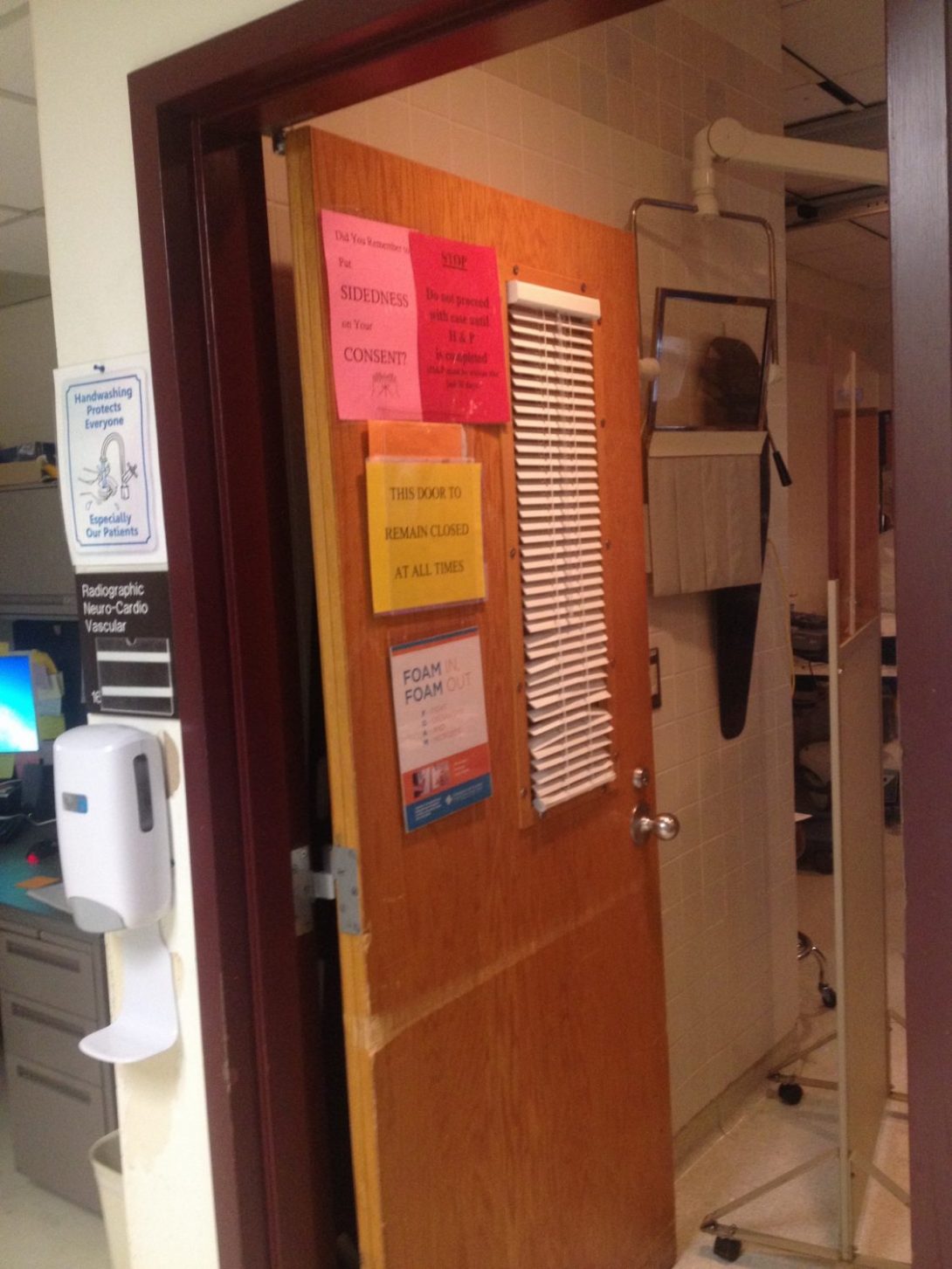

- Checklist procedure followed before, during, and after procedure to ensure right operation is happening.

- Equipment counted before and after operation to ensure nothing was accidentally left inside patient.

- Lots of equipment in the OR is on wheels and actually makes components difficult to move when other pieces of equipment are in the proximity. (Chairs and IV bags getting stuck together at the base because of how the wheeled-base is designed.

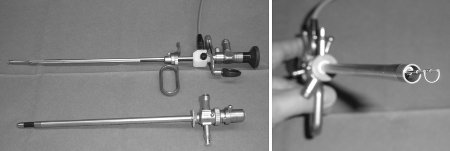

- no potentiometer for light on endoscope–because of lighting in OR, the available light is too bright.

- power supply for endoscope lights up tubing when in use.

- final drill guided by a guide-wire from previous, smaller drilled-hole.

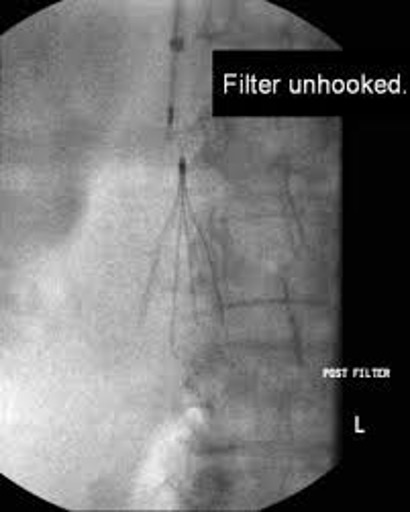

- x ray guidance used when something like a pedestal (bone growth) is in the way of drill.

- Bed was in the way for a lot of x rays and required the x ray to be repositioned several times. This becomes increasingly difficult when a patient has a large leg as well.

- Doppler device used to audibly hear blood flow into area that was previously under tourniquet for blood flow restriction.

- Prep for an OR is essentially wiping down everything and disassembling operating table when a new one is needed. After one surgery, prep took 40 minutes.

- x ray covered in plastic wrap that protects the x ray from getting blood on it, but also makes it hard to see around and the covering wrap routinely gets in the way.

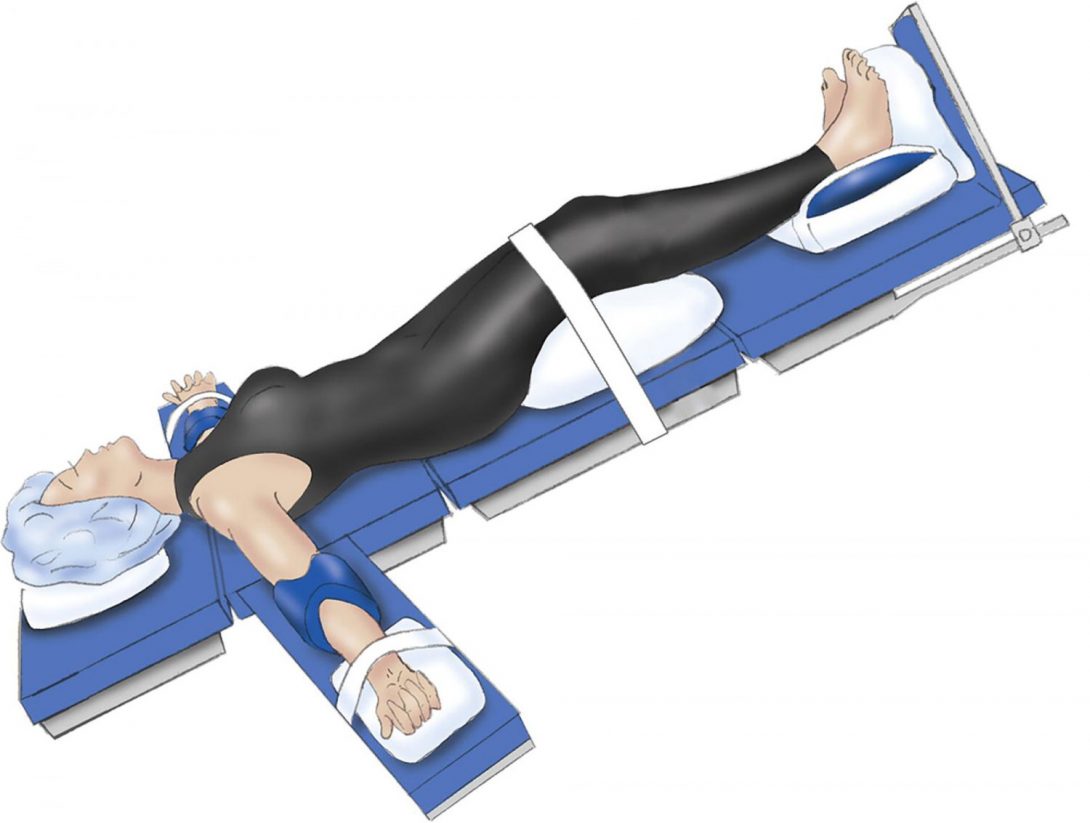

- special table was developed for certain operations that lets a nurse rotate legs and move them around without moving other parts of the patient or simply holding these body parts up themselves.

- Extra plastic shielding was used everywhere when the room needed special protection from blood (work-arounds seen here as well, described later).

- During surgery, an x ray of the ankle was needed while the leg was straight and elevated–because of the x ray, this required a resident to essentially hold up the leg with their sternum so as to get out of the way of the x ray.

- hammering pitch increases when a component is fit into proper place (components hammered into place).

Thoughts:

As far as delays go, addressing the x ray back up in clinic appears to have the most impact on patient flow.

A potentiometer in equipment involving a light in my opinion should be the standard as conditions from OR to OR can vary.

Lead vests could definitely be better designed to shield the user, but also not be as uncomfortable to wear for extended periods of times. Furthermore, a simple checkout and return of lead vests/neck guards could be implemented so that shortages do not occur at critical times.

I do not have all the facts, but perhaps when equipment for a surgery arrives it could be sent to the OR it is needed at with or without the company rep. What I saw was that the equipment for a surgery was in storage and unable to be moved by other people to the OR simply because the company rep was not there. When such a delay occurs a company rep must arrive, go to where the equipment is located, and then bring that equipment up to the OR causing further delay. If the equipment was already at the proper OR, time could be saved. I am uncertain as to how often this happens and if this type of delay is typical as I have seen other equipment sitting ready at the OR prior to surgery.

These plastic wrappings around x ray equipment could definitely be redesigned and vacuumed sealed as they otherwise obstruct the view of the surgeon and residents on top of just being in the way:

There could potentially be an extension added to surgical tables or something hanging from the sealing to attach covers onto when extra shielding from blood is needed instead of this:

Overall, if anything my last visit to the OR taught me, it’s that I have seen a lot these past few weeks, but there is definitely more to see and more that can be improved than just what I have noticed.

Rotate 180 Degrees Onco W1 1/2

Mohi Ahmed Blog

[This blog covers the first few days of the radiation oncology rotation; attending physicians are Dr. Koshy and Dr. Howard]

Summary:

This week specifically covers radiation oncology as hematology/oncology is potentially the next two weeks. We began observation of an entirely new department with a new group this week. We got a rundown of the typical happenings in this radiation oncology clinic and what to expect; we saw a few patients and attended some extra discussions. We experienced some hard talks to family when dealing with cancer and got to see just how tech heavy this clinic is compared to orthopedics. Overall, we got to see just how much contrast there was compared to the previous rotation.

Interesting Observations:

- The term for new patients is “consults”

- This clinic deals with planning radiation treatment, the diagnosis of cancer is usually a few weeks old by the time a patient is sent to radiation oncology.

- This entire clinic deals with coming up with a thorough and customized plan if radiation treatment is the designated means of treatment.

- Molds are used so that as a patient comes in for their daily treatments of radiation, they are lying down in the exact same position as every other day of treatment.

- Consultation takes 1 day and then planning (which usually takes a week more) cannot start until insurance is taken care of (usually a few extra days).

- Interestingly enough, in most cases there really is not an economy to treating patients a week sooner or later (according to the literature).

- CT, Pet, and MRI scans used extensively whereas Ortho used x rays and–to a lesser extent–MRA’s almost always.

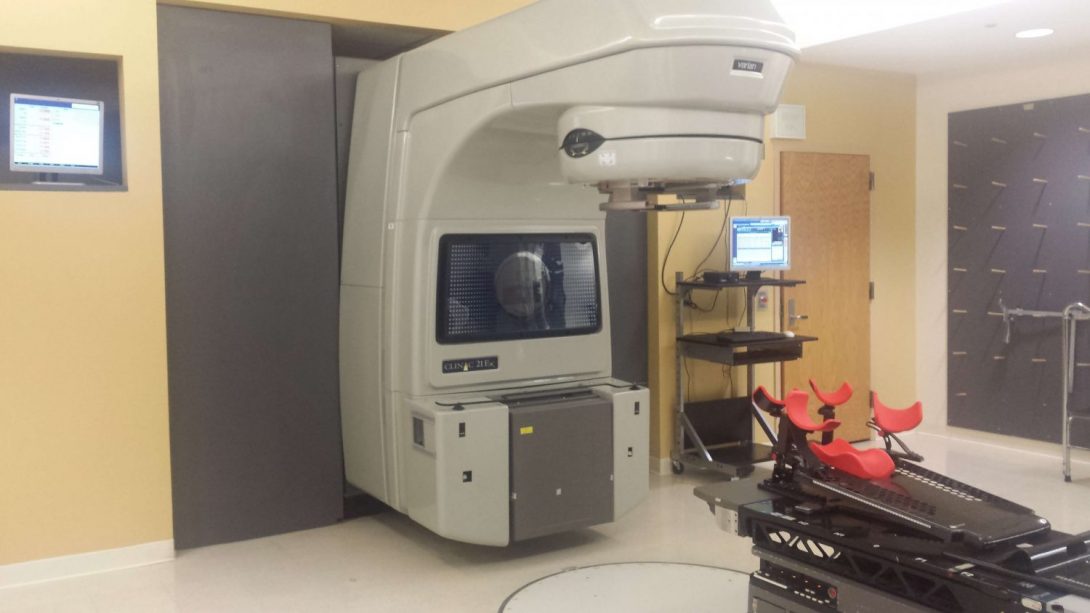

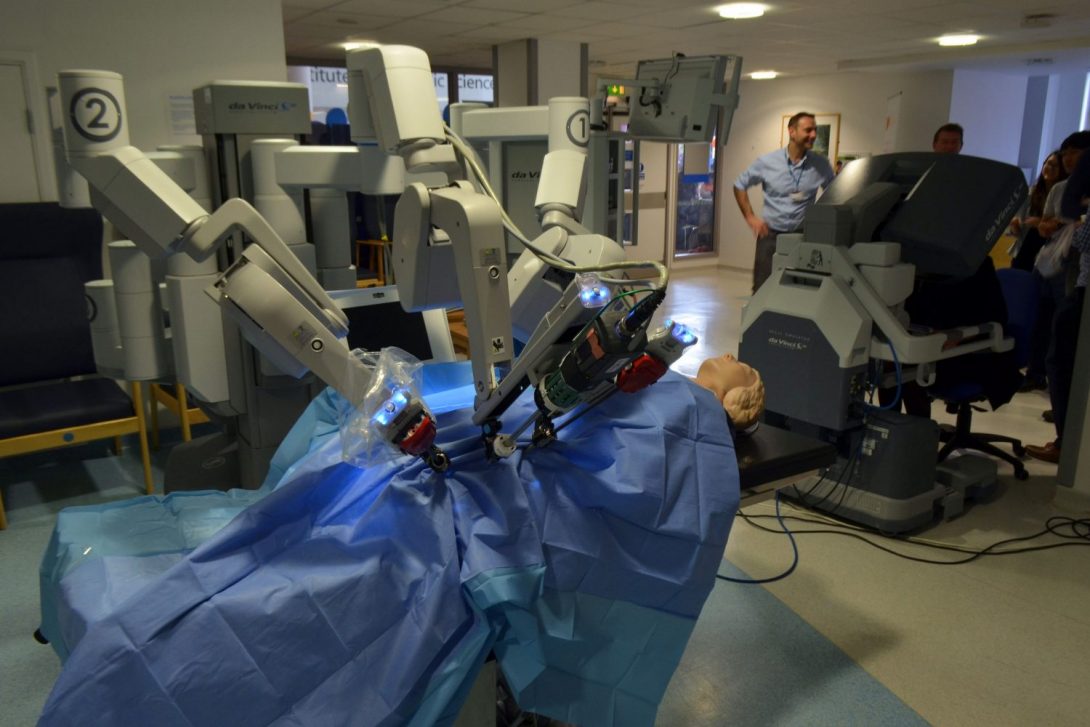

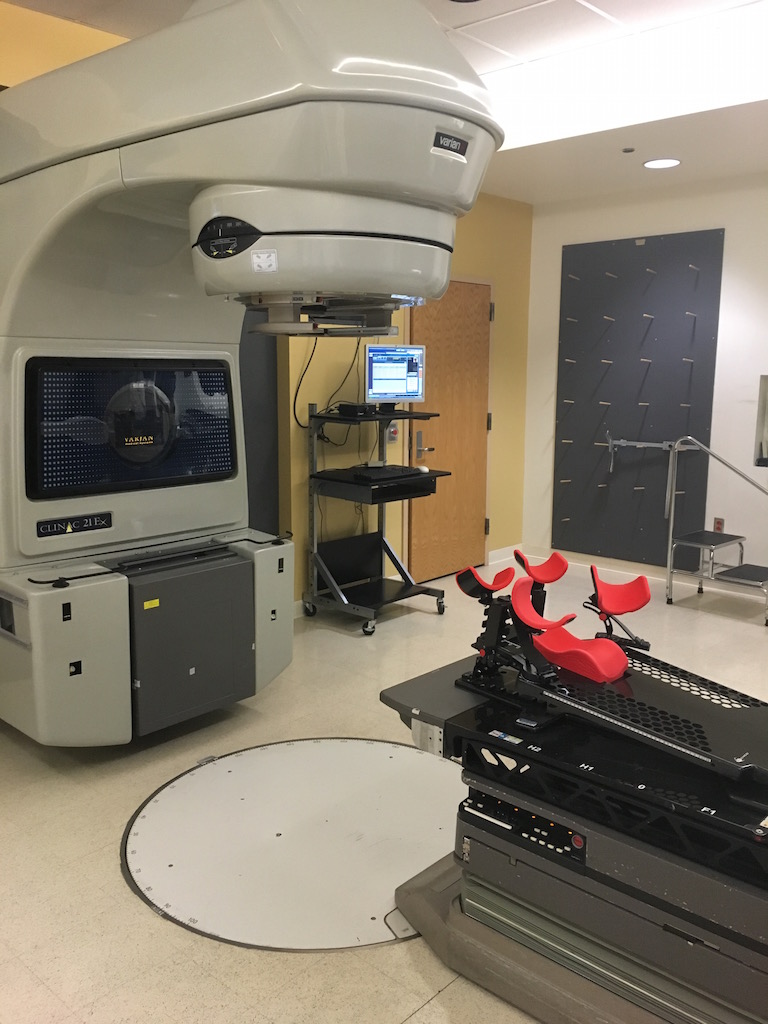

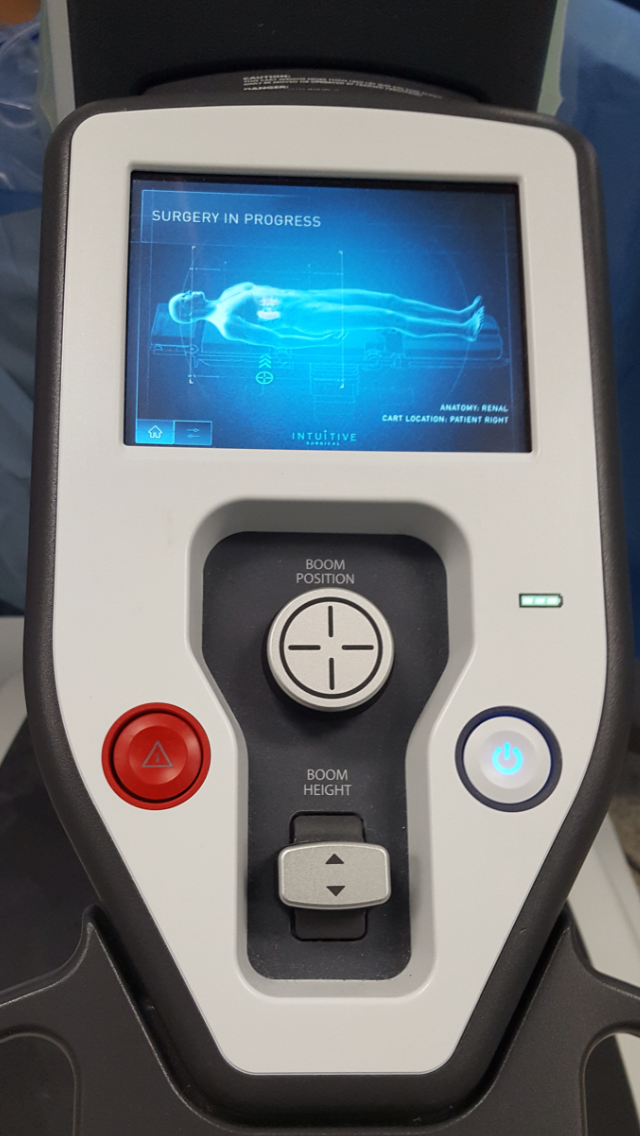

- Treatment is done via a complicated software and an even more complicated machine. Essentially a tumor is seen on a scan, a resident will draw in on all relevant “slices” of the scan the boundary of the radiation. They will also include an additional few cm’s expansion of the original trace to include cancer cells that are beginning to spread, but are not appearing on scans. Finally an additional expansion is put in to account for movement of the patient.

- The residents plan of action is then reviewed and edited by the attending, this new plan is then double-checked that the plan will not make the robot possibly impact the patient while trying to target the tumor or other perceived issues.

- Finally, a team of physicists will look at the plan to ensure that the goal is being achieved and that the goal is feasible in the first place–if not the plan is edited again.

- Overall a plan takes a week per patient’s radiation treatment.

Thoughts:

I simply cannot get over how different a clinic this is compared to Orthopedics. First of all there’s 10ish patients a day as opposed to 60-80. Each patient encounter or talk is far more intimate than a quick 30 second follow-up. Whereas the tools and techniques in orthopedics can at times seem medieval, I was genuinely made to feel that in radiation oncology the devices and treatments are truly space age material.

I may as well be at NASA or CERN or Fermilab. Or at least it feels like it tech-wise.

We have seen a few areas we think we could improve and I will expand upon this in the next blog post. Pictures are coming.

Hint: It is notpatient flow.

Why Do You Put Up With This? [Onco W1 2/2]

Mohi Ahmed Blog

[The following covers the latter part of my first week in radiation oncology; Dr. Koshy and Dr. Howard are the attending physicians.]

Summary:

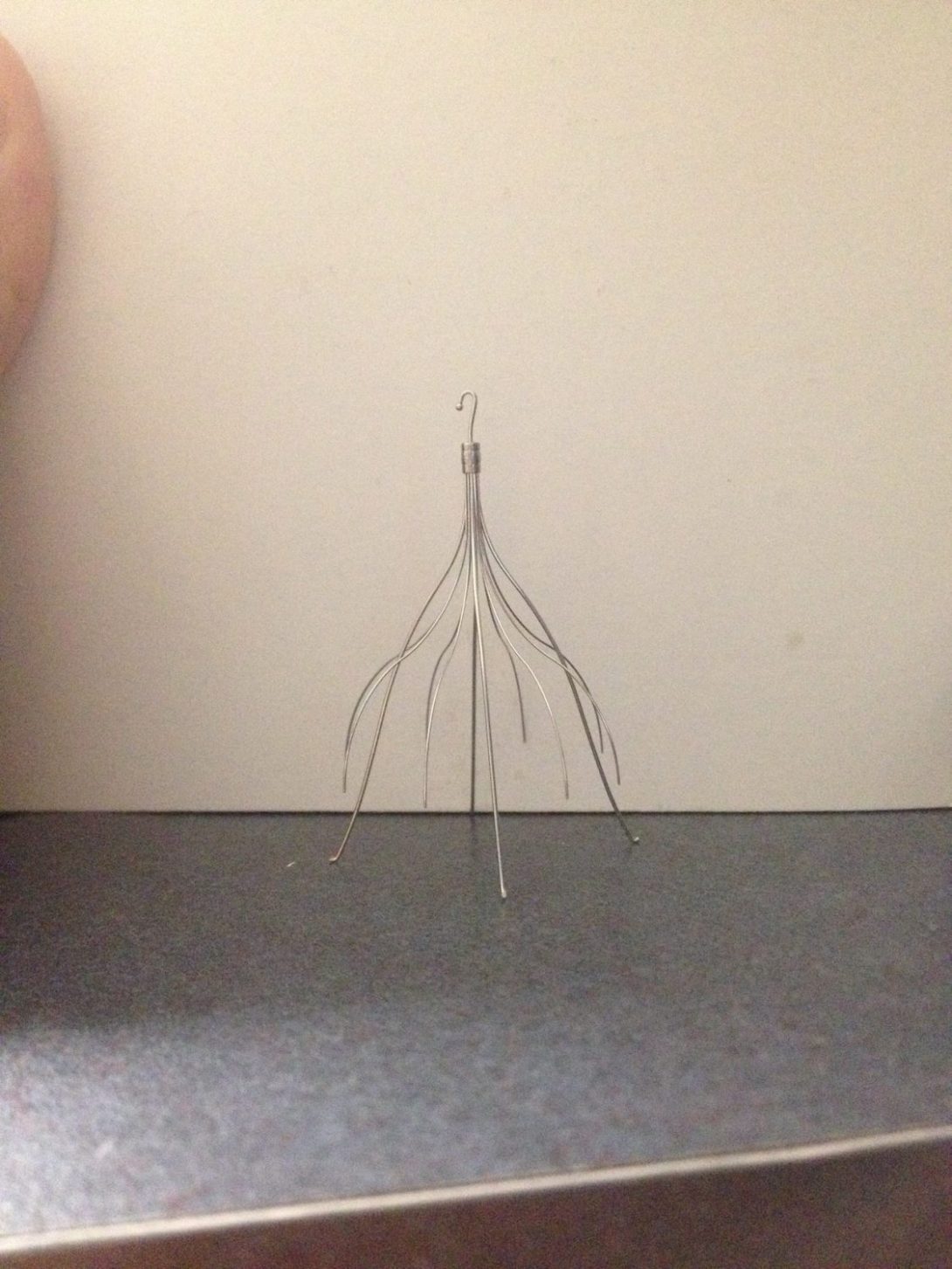

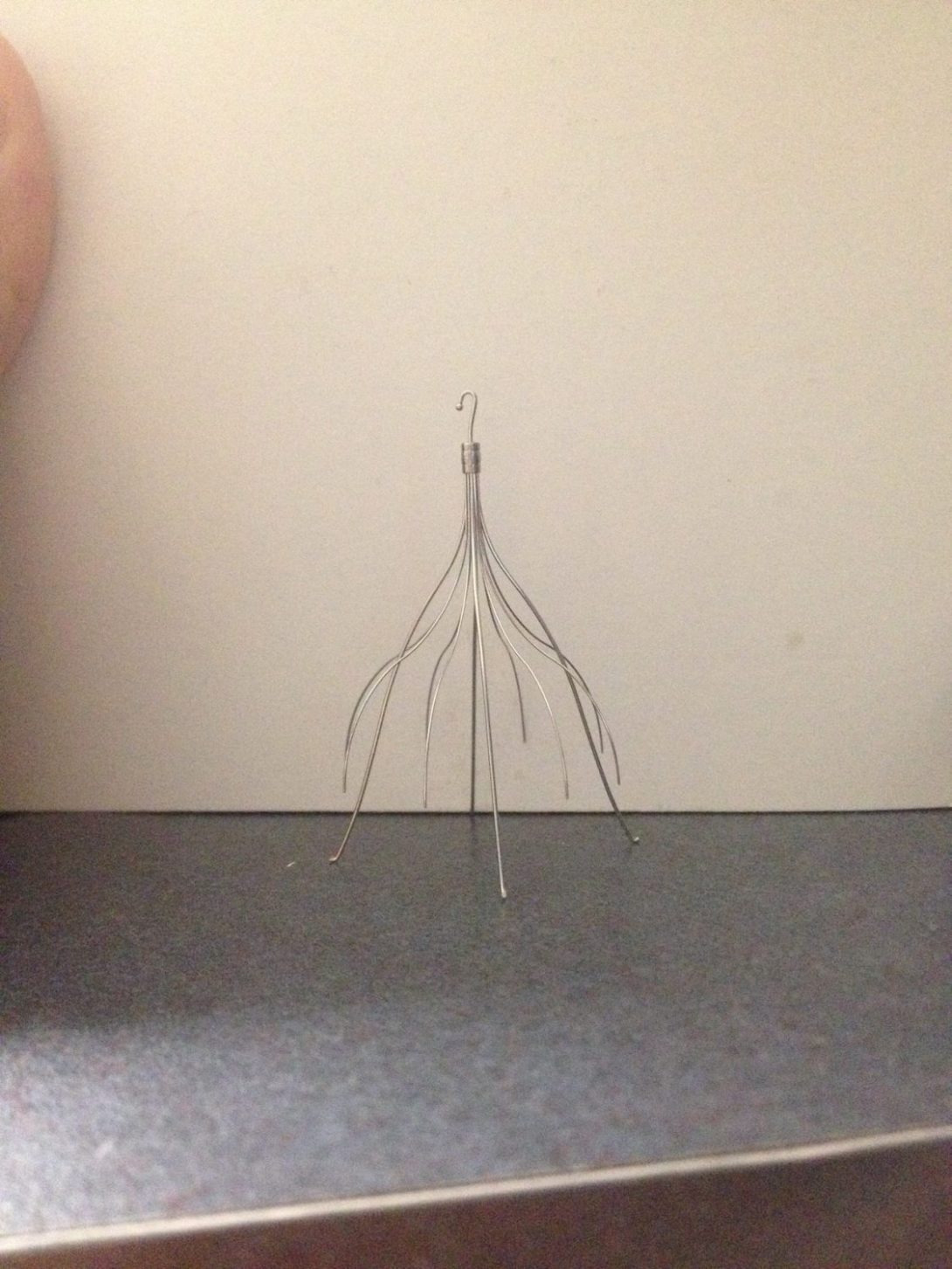

After we saw the brachytherapy of a tumor we were shown a sterilized toolkit used to spread open the human vagina and deliver a dose of radiation to tumors in certain areas while minimizing surface toxicity to surrounding tissues. Brachytherapy essentially involves a wire being strategically placed near a tumor where it can then deliver a radioactive isotope and then withdraw that isotope after the allotted treatment.Upon examining this tool, we noted complaints the residents had of using this device as it spreading mechanism and assembly appears flawed. It is difficult for the residents to lock the device into a certain position. Furthermore, it is uncomfortable for the patient as a certain component of its spreading mechanism pokes the inner thigh of the patient and is evidently very uncomfortable. To combat this outcropping piece and also make sure the tool holds properly, the residents wrap tape around this section. The disappointing part is that this tool is fairly recent in design.

Furthermore, during this brachytherapy, in order to keep radiation away from the thigh, the wire where the isotope travels through is kept away from the legs with just some sheets/padding with the intention of using the inverse square law to their advantage. At first I thought this was a significant workaround the residents were performing, but it almost appears as though unless the tool itself is redesigned, this problem is not economically worth solving with some kind of holding mechanism.

We also got to see a patient get radiated as a means of compromising the patient’s immune system and degrading the bone marrow in order to be more accepting of a relative’s bone marrow transplant. This procedure was essentially placing the patient in a secure room, blasting them with radiation of a specific dose and at a certain distance away for a certain time as they lay in a glass box. Blocks are strategically placed around the patient to trick the computer software into thinking the patient is shaped like a perfect rectangle to ensure no area of the subject is missed.

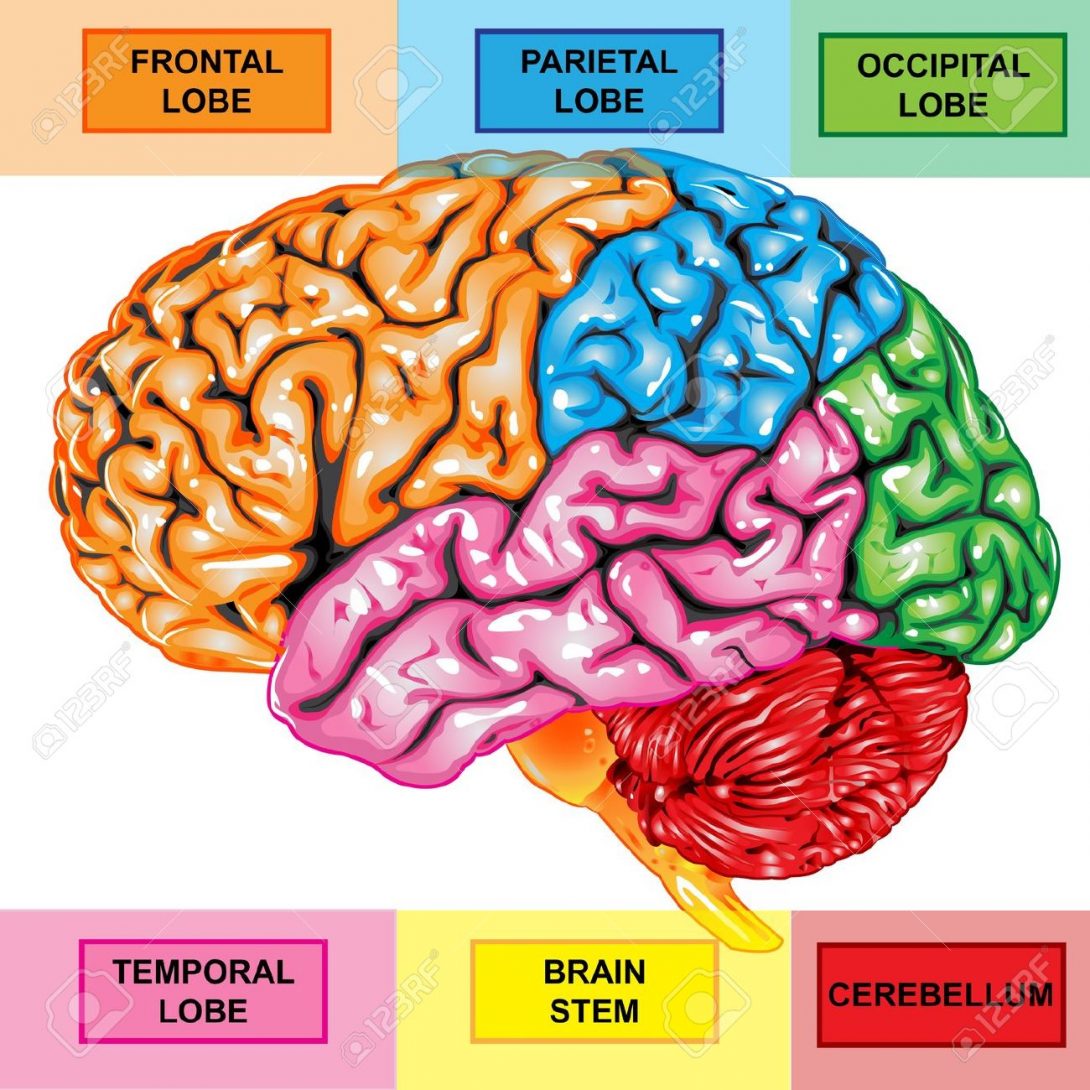

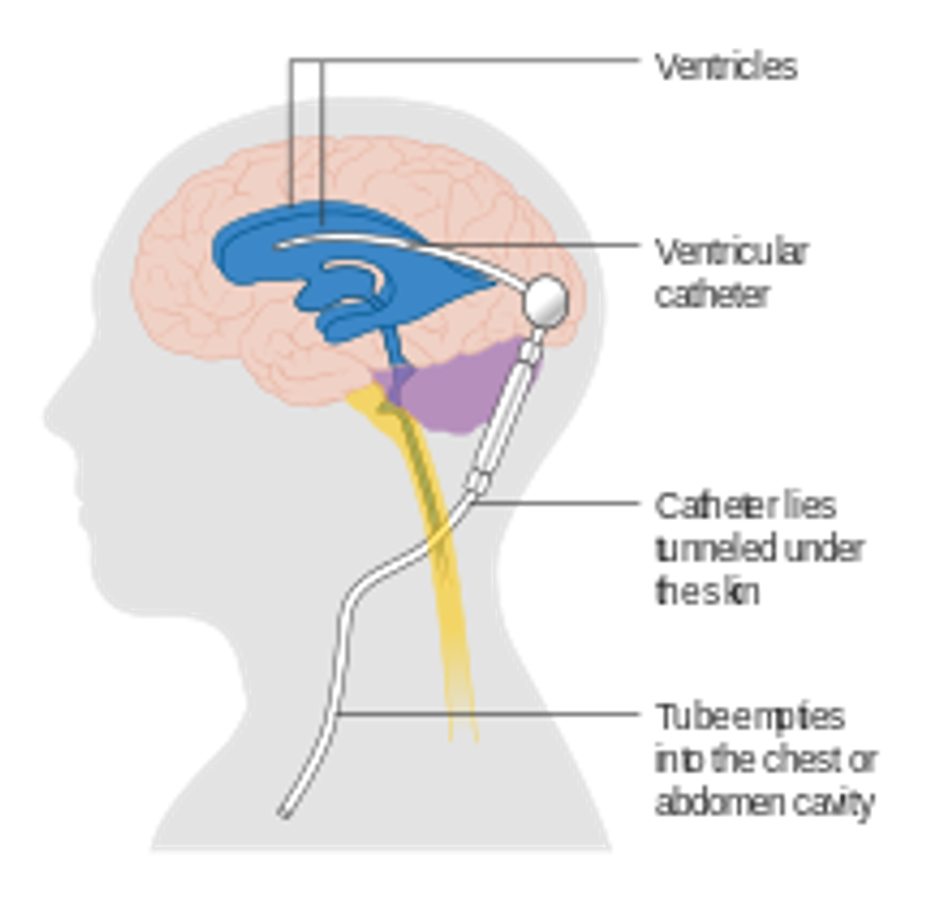

We also sat in on a Cerebral Spinal Fluid tumor board meetings. Like the previous tumor board, this meeting brings physicians from any related area regarding a tumor so that its treatment can be agreed upon by consensus. For example, a tumor in the brain requires that radiation oncology is present alongside neurosurgeons and other specialists to truly determine what the best course of action is for a given patient. This is only possible because of the low patient volume. However, some patients can be addressed at all if certain specialists are missing or if whoever is to be presenting the patient is unavailable. This happened a to certain extent at the meeting we went to and if it was any worse, there most likely would have been no point to the meeting in the first place.

We also got to see the translating service IVAN in use and simply put: it’s terrible.

Notable Observations:

- Ivan translator, press a number if language is not commonàgets outsourced to another translating service with same dialtone and again asking for common languages àselect uncommon language again àget connected, immediately disconnect and need to restart completely before finally getting a Ukrainian translator. Essentially the first 9 languages for the hospital’s translating service and the outsourced one is the same yet this is not taken into account when the call is outsourced.

- Login in time for residents is a redundant process that takes a full 2 minutes. This login is done fairly frequently as the computer logs out during the duration of each consult. There can be approximately three consults an hour which is 6 minutes spent logging in per hour. Over the course of an 8 hour day this ends up being ~48 minutes a day spent logging on to a computer through a very redundant process. This process involves signing in to several locations through software in order to have access to the next/current patient’s entire file and scans.

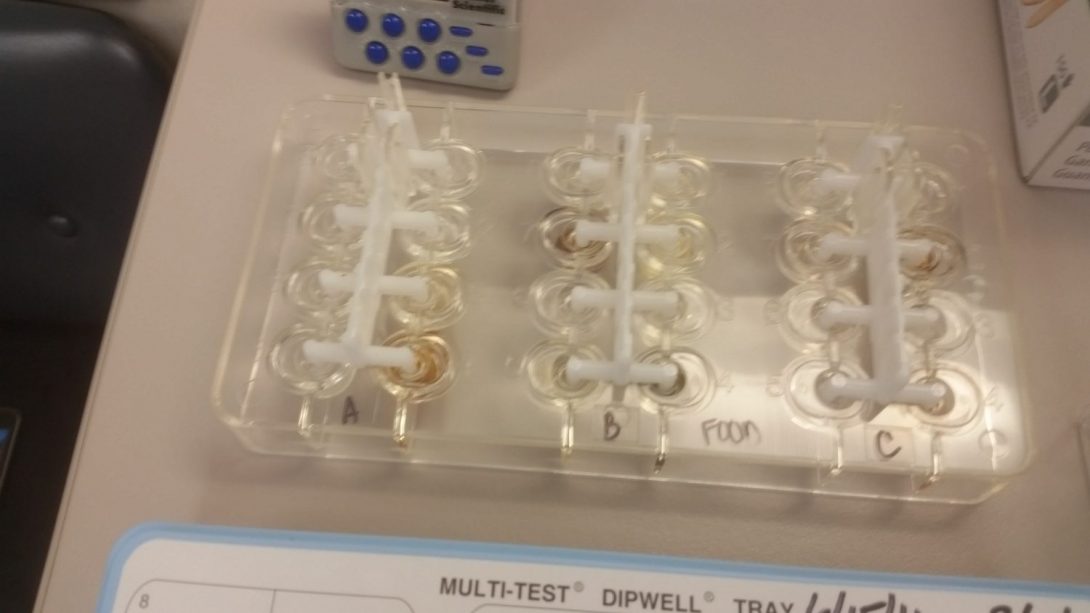

- The aforementioned spreading tool used with radiation has caps at the ends to prevent radiation build up. These are tan plastic caps that insert into a grey metal tube. They routinely get lost and are hard to see due to their lack of contrast.

- In consulting rooms, there are curtains used for what I assume is privacy if a patient needed to change into a gown. This curtain is position so that it can cover half of the room when fully opened. The location of the track these curtains follow however goes from a patient chair to the exit door. When not in use, this curtain always gets caught in the door.

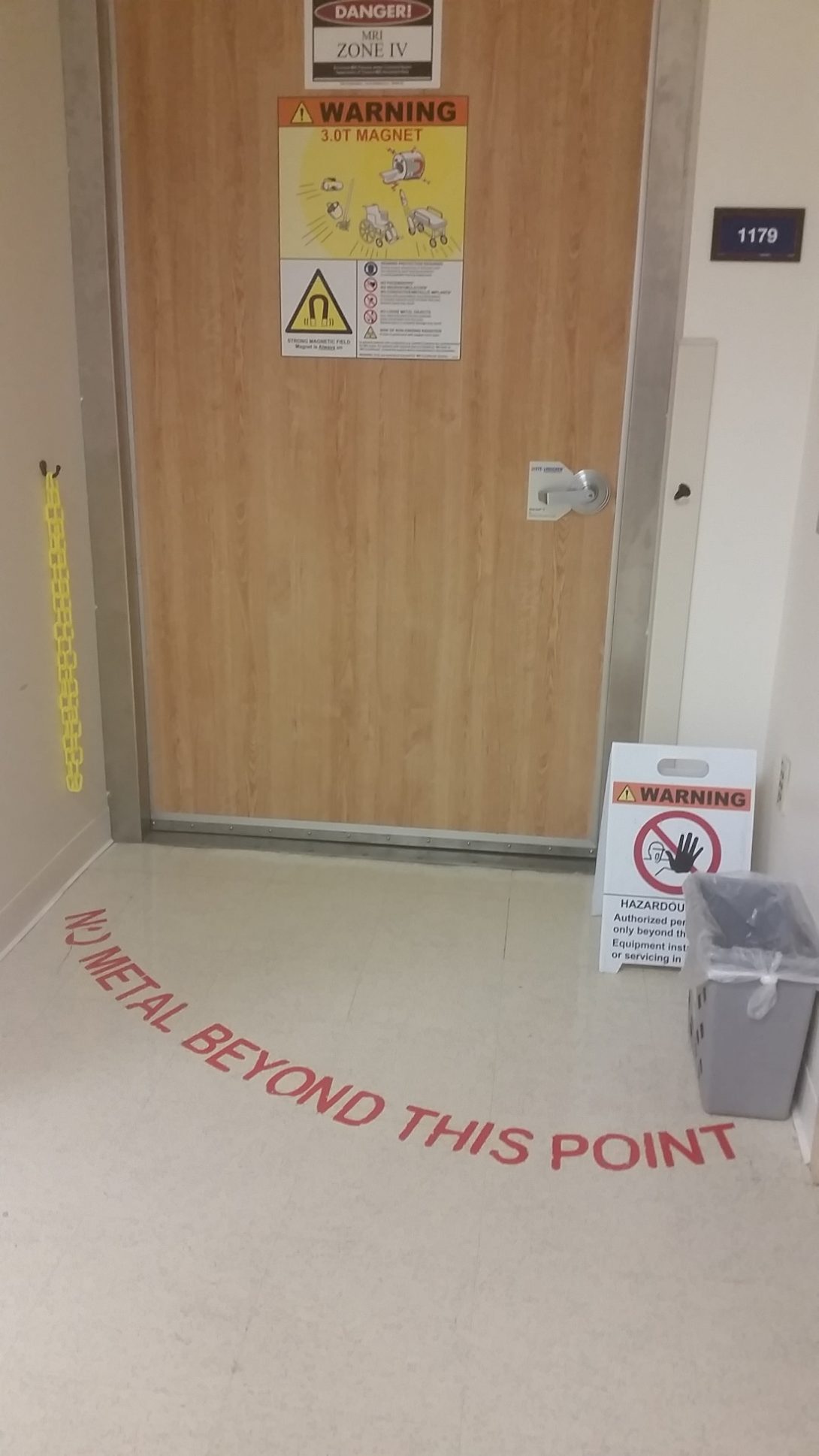

- The room with the linear accelerator has a vault door and lead shielding built into the building. The radiation cannot be turned on if the vault door is not closed.

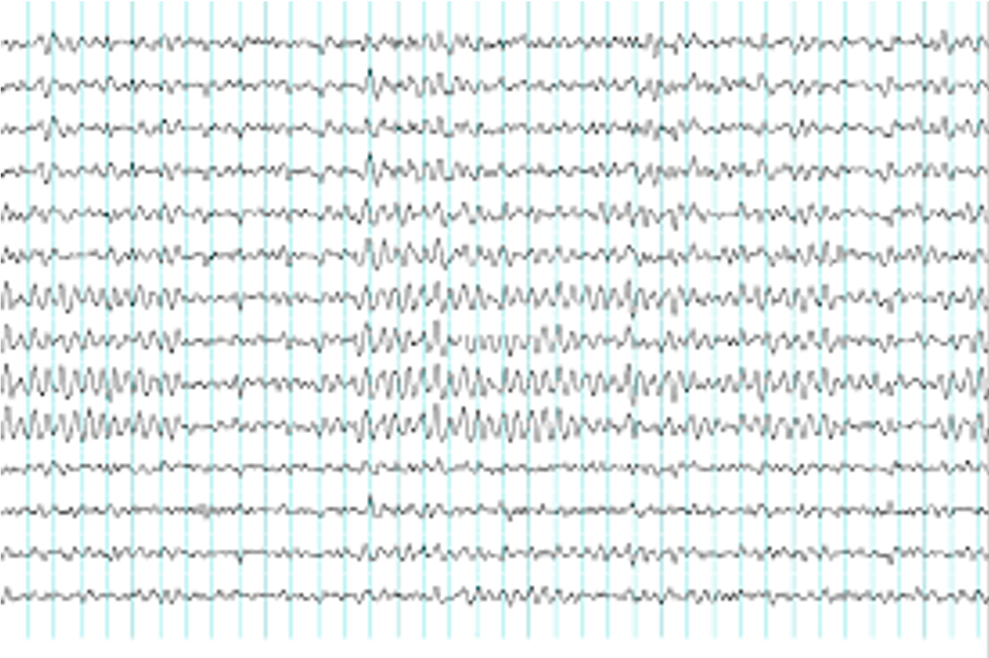

- For radiation oncology, residents and the attending physicians spend a lot of time looking at different scans as they search for tumors and whether or not they have metastasized. They look through a human slice by slice and also sometimes inject a dye or a substance that shows up on scans to track if a certain fluid is moving where it should or if sugar is being metabolized where it should. I noticed that both the attending and residents spend a lot of their day scrolling due to the nature that the images are taken in slices.

- The scans are observed a large greyscale monitor. Why this monitor is in greyscale is unknown.

- Some scans are meant to be in color, but are again viewed on a greyscale monitor such that the high and low ends of the images color scheme or both dark grey—these scans require that the resident or attending view the images on a different screen.

Thoughts:

I’ll have to ask an attending next chance I get as to why these monitors so routinely used for scans are only in black and white when one fairly common scan, specifically of the brain, needs to be in color.

I believe the aforementioned tool used to treat tumors throughout the female reproductive system is flawed and rather than attempt to fix something in the clinic as a whole, this is one component that is routinely used that our group could improve upon significantly by modifying the tools functional mechanisms. This too is another area we will potentially focus on improving. Monday begins the start of a related rotation through hematology/oncology. I will have to compare the two rotations to see if there’s a better focus for the group to pursue. However, I will have to return to radiation oncology as I intend to interview the final people in the radiation therapy planning: the physicists.

[Author’s note: This post is missing pictures, they will be uploaded tomorrow].

Red Blood Goes In, White Blood Cells, Red Blood Cells, and Plasma Come Out [Onco W2 1/2]

Mohi Ahmed Blog

Summary:

This week so far has left me dazed. After a quick week in Radiation Oncology we’re now with Hematology Oncology with various physicians and events to observe. I plan on returning to Radiation Oncology to interview the physicists and see their role in the radiation plan.

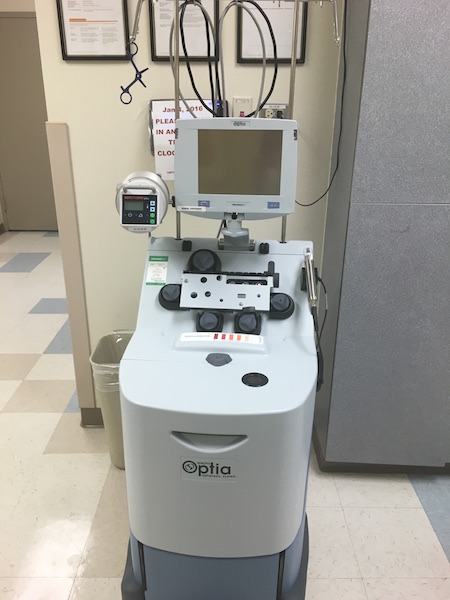

Thus far we got a crash course on hematology oncology specifically with leukemia and bone marrow transplants and got to see white blood cell collection and the machines used to accomplish this as well as the cell counting and freezing procedure for this inevitable transplant. Tomorrow I believe we will actually observe a transplant.

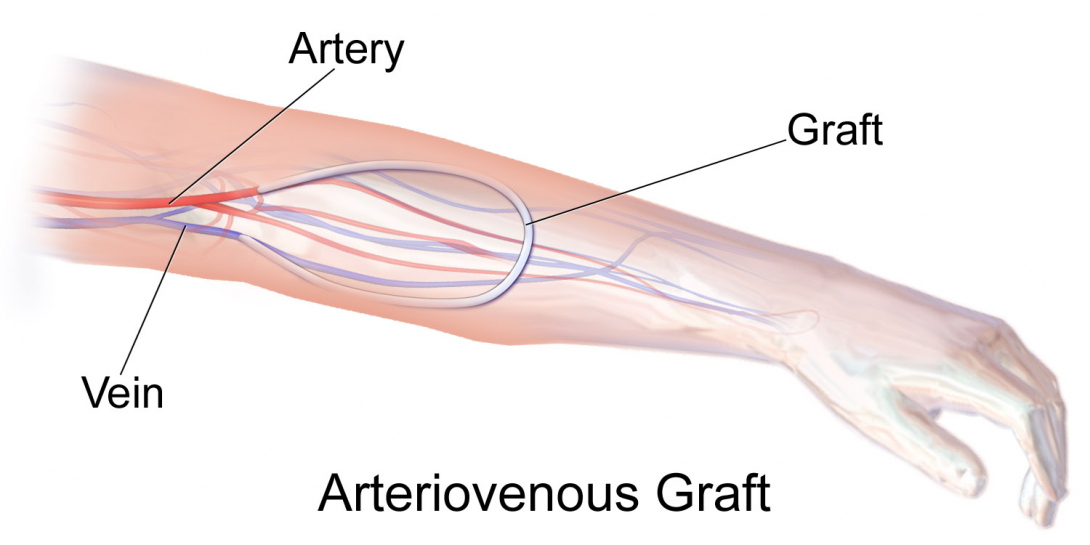

Notable Observations:

- Autologous bone marrow transplants is the transplantation of one’s own bone marrow. The initial collection is done right before chemotherapy which then destroys the remaining bone marrow. The collected bone marrow stem cells are then injected back into the original host. This bypasses the need of having a donor and the chance of rejection. Under certain conditions, an allogeneic transplant is still required and sometimes will be done if there is only a half-match between the donor and recipient.

- There is a 25% chance a sibling can be a donor to another sibling. In this case, this allows the chance of the only transplant procedure where the patient takes in a new immune system.

- The Graft vs Tumor effect is that donor cells attack a host’s cancer cells because they are viewed as “foreign.” The risk is that these donor cells also can go on to attack other cells in the patient’s body known as the Graft vs Host disease.

- Chemo doses are periodic in nature because a strong dose would completely destroy the bone marrow and potentially kill the patient. Chemo must be dosed and then allow the body to heal before taking another dose.

- New blood collection devices can continuously uptake and separate blood into its cellular components (red, white, and platelets) whereas not too long ago this was an interval process.

- For cryopreservation this lab uses a controlled rate freezer to purposely cool a collected sample by 1 degree Celsius a minute (varying) before ultimately freezing with liquid nitrogen to -180 degrees Celsius. This is done to avoid damaging the sample.

- Two machines in the lab use disposable kits that require a new kit perpatient. One kit for one machine requires an expensive reagent putting the kit’s price at around 4,000 USD and the other machine has a kit that routinely costs 300-500 USD.

- Companies that manufacturer these devices stop supplying the kits when they create a new device to force hospitals to buy their new device and respective new kits.

- Sample is counted multiple times throughout collection and freezing; if anything goes wrong they can look back at what part of the process caused an error.

- The lab is evaluated by an outside company that essentially sends them a sample to analyze and compares their results to predetermined values.

- Navigating through insurance is a common topic in meetings for nearly every single patient.

- 7-AAD is a nucleic dye used in this sample collection and stains dead cells which are important to account for when prepping a sample for transplantation.

Thoughts:

I am left feeling devoid of deeper thoughts; a major portion of the lab procedure and environment for cell collection, counting, and storing is something I am already very familiar with.

Keep in mind it’s only been a few days, but compared to radiation oncology, we have only seen the surface of a variety of different fields so I do not even have an inkling of a potential innovative space.

That being said, our schedule is packed this week so there’s still so much more to see.

Clinic & Chemo [Onco W2 2/2]

Mohi Ahmed Blog

Summary:

Towards the end of our week in Hematology Oncology we got to see the clinic run by Dr. Rondelli as well as the contiguous chemotherapy infusion clinic. This observation period was split in half by our group of 4 where we had two of us alternate between the two clinics as a means of tracking observations throughout the entire day instead of isolating them to a given time period.

Under Dr. Rondelli, I personally saw the follow-ups for routine bone marrow transplants as well as the rarer haplo-donor transplant. The haplo donor is used when options are limited and the donor selected only matches “half” the markers for an ideal transplant. These usually do not work as well and are likely more symptomatic afterwards–but they may be the only possible treatment.

We also viewed how a chemotherapy clinic is run by following the lead nurse in charge of infusions and scheduling. I saw blatant troublesome areas making this nurse’s life more difficult, but it appears among the frantic nature of clinic this nurse would rather just work with the problems presented instead of spending extra time looking for a preventative means.

Notable Observations:

Hematology Clinic:

- Majority of hematology clinic patients are follow-ups (at least for this given day).

- Conversations with patients are very long and intimate.

- The ability to speak Spanish helps tremendously in terms of patient flow–this is likely specific to UIH and not general to all U.S. hospitals.

- Follow-ups continue well after procedure and a good outcome is achieved; the haplo-transplant patient was in for a follow-up nearly a decade post-treatment.

Chemotherapy Clinic:

- Head nurse has a main chart with room number and time as the X- and Y-axis respectively. This chart tracks what patient is in what room, is highlighted if treatment is currently going on, or crossed out when complete or considered a “no show.” Quite often patients need to be moved around resulting in arrows all over the chart making it more akin to an American football playbook.

- Chemotherapy sessions take at least 30 minutes; some sessions take over an hour and for these patients a room with a bed is reserved. When a patient is late, that entire rooms schedule is delayed.

- As an obvious work around, the head nurse bought themselves a kitchen timer for cases such as when a patient is not responding well to pre-chemo drugs and needs extra infusion time. The alarm is set and goes off alerting the nurse that the extended time is up and the patient should now be ready to actually start chemo.

- There are 9 rooms for chemotherapy. Only a few have beds which can be used for patients requiring longer infusion time. If the patient is immunocompromised or an inmate, they must be in a room alone. These limitations must be concerned when scheduling patients for the day.

- When a patient schedules a chemotherapy session, they are simply placed into a room without the aforementioned constraints taken into account. The head nurse then must reorganize the scheduling to meet the constraints the night before the day in question–hence the football diagram chart.

Thoughts:

I was told the reason for this chemotherapy scheduling conundrum is that if scheduling was taken into account up front, many patients would need to be turned away. Even after several clarifying questions, I still could not deduce why exactly this system was set up the way it was. I will attempt to truly get to the bottom of this.

It was interesting to see that the ability to speak Spanish was important enough that Dr. Rondelli made active efforts to speak it. Coming from an Italian-speaking background, it appears he has picked up on words and phrases over the years and then used is Italian background to try and fill in the gaps. I have seen physicians appreciating the ability to speak Spanish through other departments as well. This looks to be about keeping patient flow fast and at least in other departments all about avoiding using translator services.

“It’s All a Part of the Plan” [Onco W3 1/2]

Mohi Ahmed Blog

[Authors note: this is going to be an irregular post compared the previous ones focusing on radiation therapy planning. I finally interviewed the medical physicists on hand and now had a complete picture of the entire radiation plan.]

Summary:

Our time in hematology oncology is winding down and I thought this would be a good time to note the radiation therapy planning when a beam is needed (as opposed to brachytherapy which involves a guide-wire and a radioactive isotope). We’ve seen a variety of patients in a variety of locations during various points along the combating-cancer timeline.

Content:

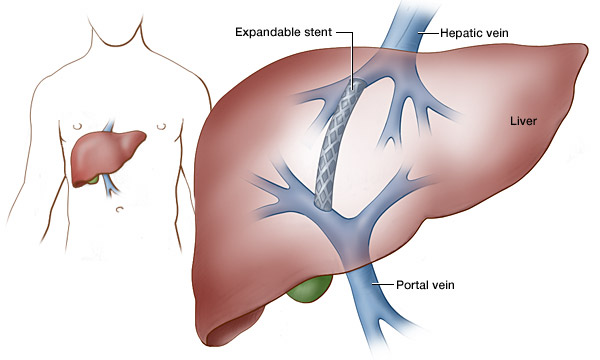

When it comes to radiation therapy involving a beam, the idea is to use a linear accelerator which in simple terms fires electrons at tissue, dislodging other electrons causing the release of photons in the form of high power rays that purposely damage cancerous/necrotic tissue with heat. The amount of radiation is measured in Gray’s (Gy) and is a measure of Joules per Kilogram. The a lethal dose to the overall human body is as low as 10 Gy with serious complication and poor outlook with as low as 2 Gy.

A radiation therapy is put into effect for a list of cancers too large to list here. At first a resident goes through CT/MRI/MRA scans of and highlight areas of the cancer to be treated with the radiation. In general, tumors are targeted with much higher than the lethal dose of radiation such as 30 Gy simply because it can be localized to a target area and the volume being radiated with 30 Gy can be comprised of 30 beams each dosing 1 Gy each.

Next the attending physician looks over the contour plan and usually increases the volume given radiation to account for microscopic spread of the cancer not showing up on scans. Furthermore, they double-check that the beams will not be radiating vulnerable tissues.

Following that, a dosimetrist figures out what amount of beams, at what angle, and at what duration the radiation must be given to achieve the desired dosage to a given tumor. Quite literally this person figures out how to achieve the dosage to a tumor that the radiation oncologists want. The dosimetrist essentially runs the contour plan on a “phantom” AKA a dummy that matches previously done CT scans.

The medical physicists is the last cog in the machine. These people look at the plan, the dosage prescribed, and figure out if this is feasible. They make sure the machine will not accidentally physically damage the patient. The dosimetrist is technically a part of the physics team. With the dangerous nature of radiation, the physics end of the plan is entirely about double-checking everything. The medical physicists independently look at the dosimetrist’s plan to ensure that the calculations and plans are all in alignment.

This entire process takes an entire week. This may seem long, but when radiation is in use, it is clear shortcuts cannot be taken.

Kushal Basnet Blog Heading link

-

Kushal Basnet Blog

First Day

Kushal Basnet Blog

If I am going to be honest, I was pretty nervous coming into this program. I did not really know much about it and I am not comfortable going into things I don’t know much about. I did have some friends in the program, so it wasn’t all bad.

Waking up was pretty much the hardest part of the day. I was accustomed to staying up all night and waking up late, because it was summer time. I put that all behind and headed to orientation. My heart rate started to go up as I entered the innovation center, but my nerves calmed down after I saw some familiar faces inside the building.

The program started and it went as I was expecting it to until the guest speaker came in. The guest speaker had us do various activities to warm up things. Most of the activities were rather odd, but they did have some sort of a purpose behind them. There was one activity where we had to get into groups of two and one of had to play the part of a time traveler and the other had to explain to the time traveler what a cell phone is. The purpose of this activity, I like to think, was to help improve our communication skills. I soon found myself enjoying the orientation and was a little sad when it ended. The Clinical Immersion program had officially started and we were sent off to our rotations.

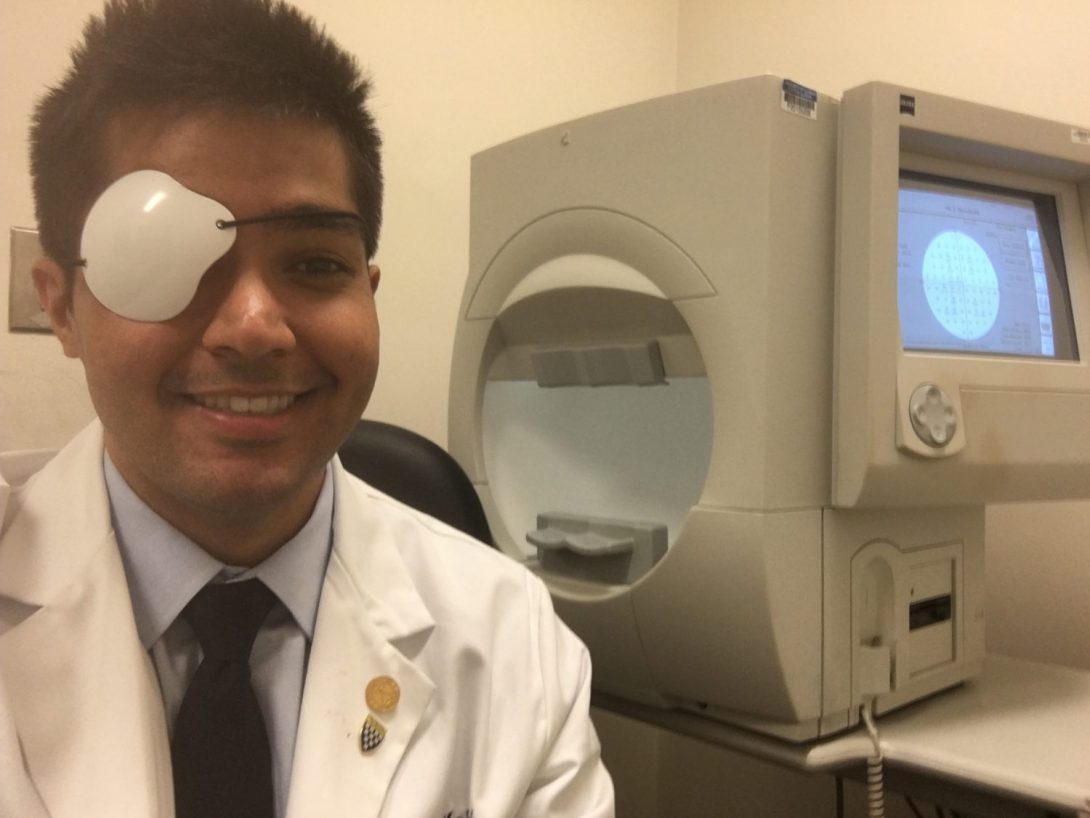

With my group of 4, I headed to the eye and ear clinical at UIC because I was placed into ophthalmology for my first rotation. We got to the clinical not knowing what to expect, but we soon found out Dr.Sugar, who is our clinical leader, is super nice and very willing to help. He showed us around the building and took us to each of the department of ophthalmology. The tour was very detailed and Dr.Sugar explained many of the equipments the doctors use at the clinic. He was also very much against the idea of taking notes during his tour, so I have to leave out much of the details. The whole thing took about 2 hours and after we were allowed to leave after.

My first day was full of nervousness and excitement , but I got though it and I found myself really enjoying my first day. I was so tired at the end of it I took a nap as soon as I reached home and before I feel asleep I thought about how much I am looking forward to the rest of the program.

The first week of Clinical Immersion Program

Kushal Basnet Blog

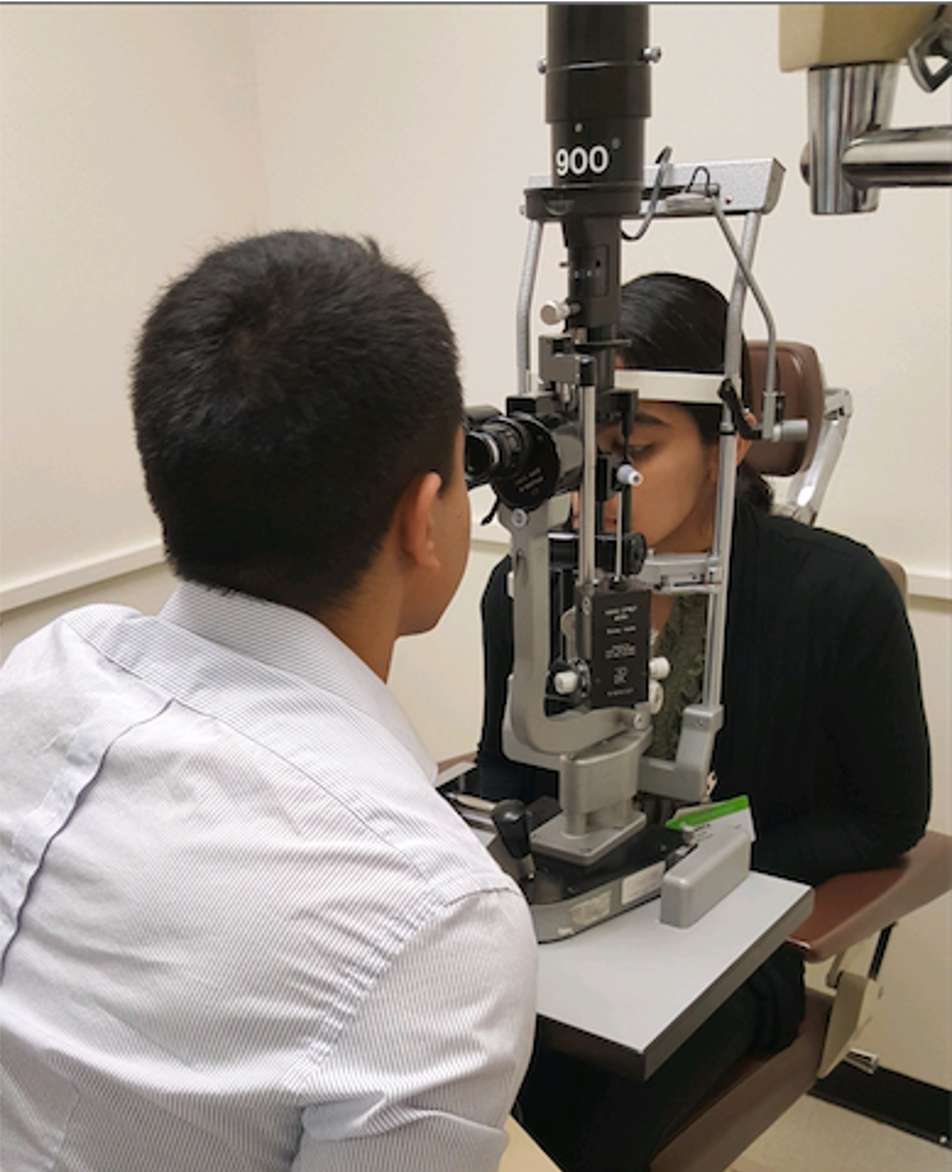

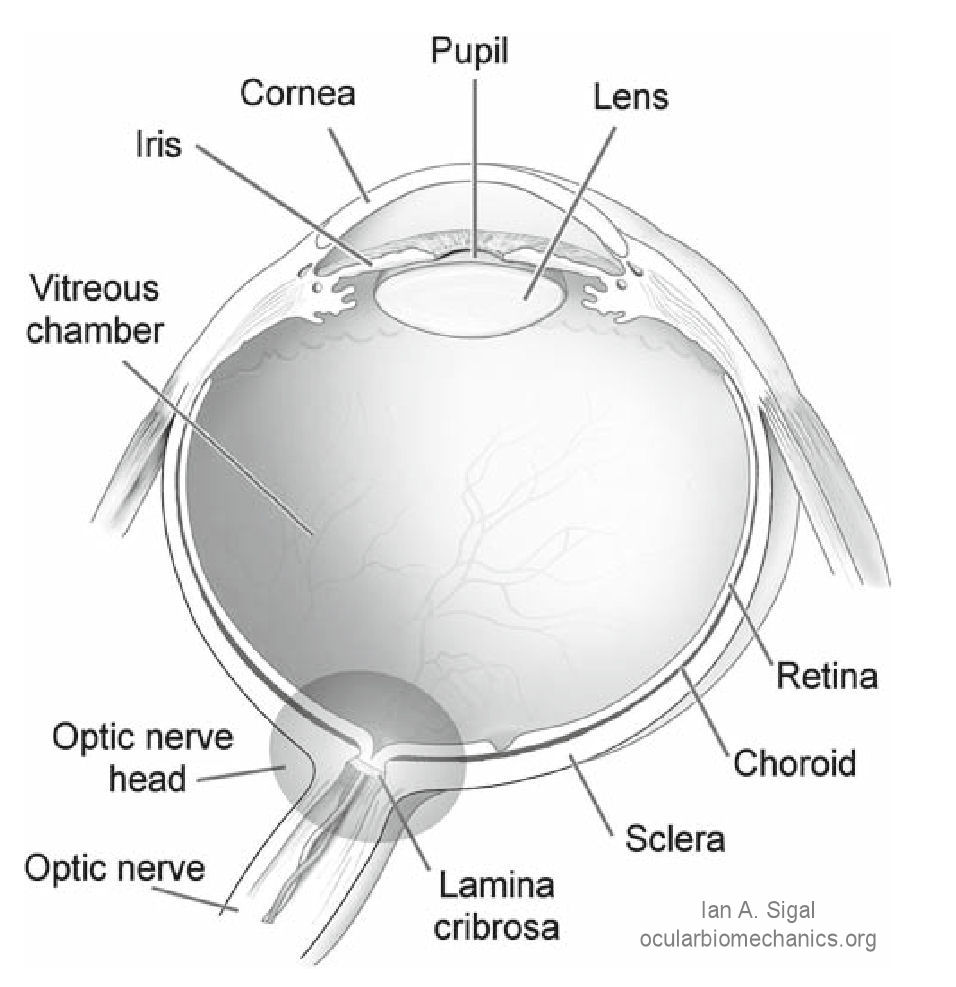

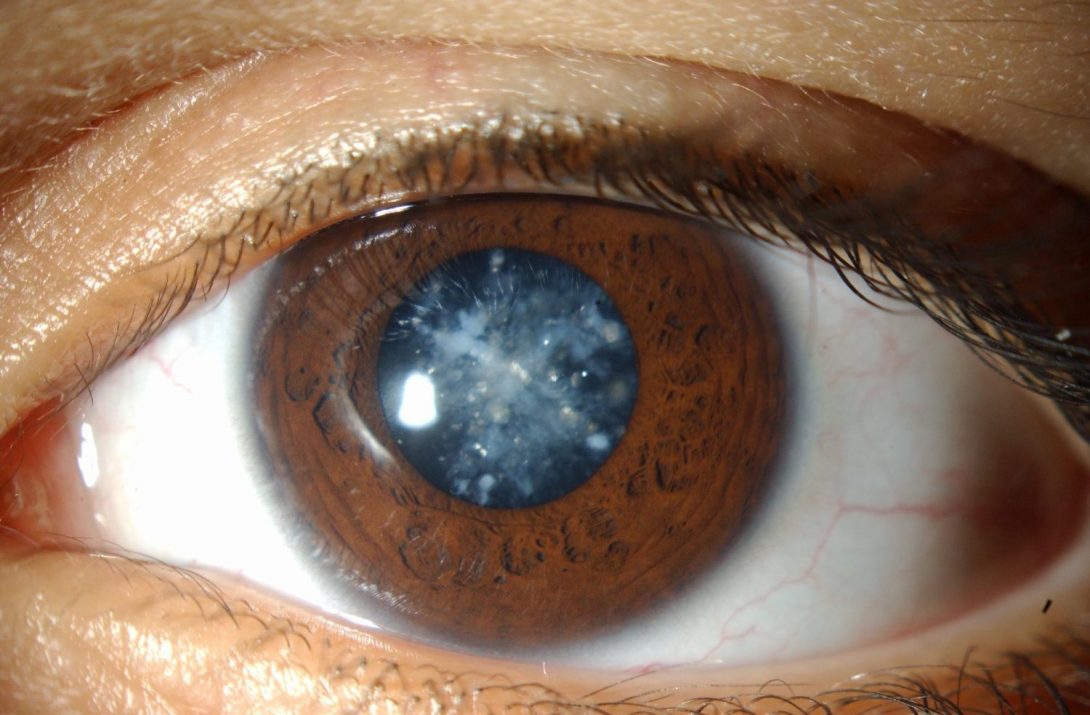

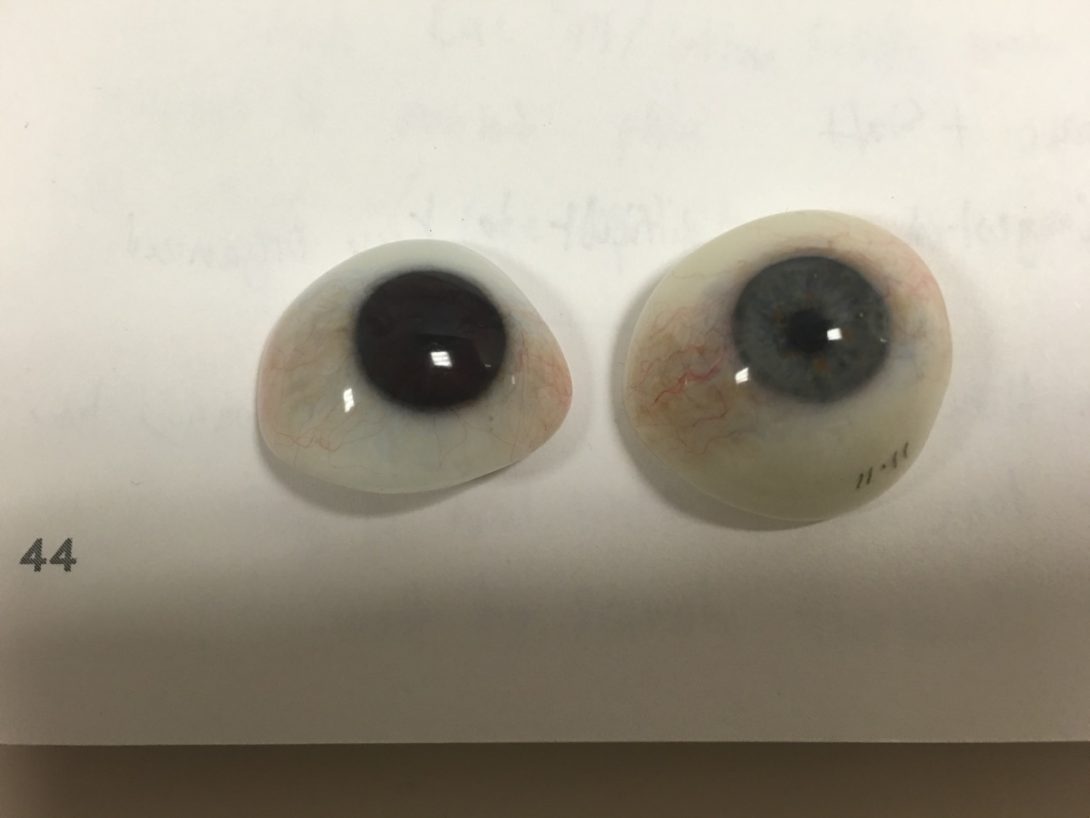

The next three days after orientation were rather hectic. I was put into the cornea department of ophthalmology with Dr.Sugar, who happens to be the head of the department, for day two of my internship. Before I go into detail about my time with Dr.Sugar, let me tell you that he might be the coolest doctor I have ever met. Most of the day I was in Dr.Sugar’s examination room observing the many patients that came in to get checked in. Almost all the examinations that Dr.Sugar did were through a medical device called a slit lamp, which is a lamp that emits a beam of light into the eye. This allows the doctor to view different parts of the eye and examine it for certain diseases and abnormalities. The slit lamp also has a side binocular; so multiple users can view through it. While Dr.Sugar performed examination of the many patients that came in that day, I got to view what he saw during the examination. It was a really exciting experience. I can’t go into much detail, because Dr.Sugar is very much against taking notes, but I ended up learning many new things. Most of the patients had cornea or lens replacement and you could see that using the slit lamp. If the patient had a lens replacement then a reflecting of light would emit from the eye when it was exposed to the light of the slit lamp. The whole day Dr.Sugar was very informational and sometime even threw in a joke or two. The whole day was a fun learning experience.

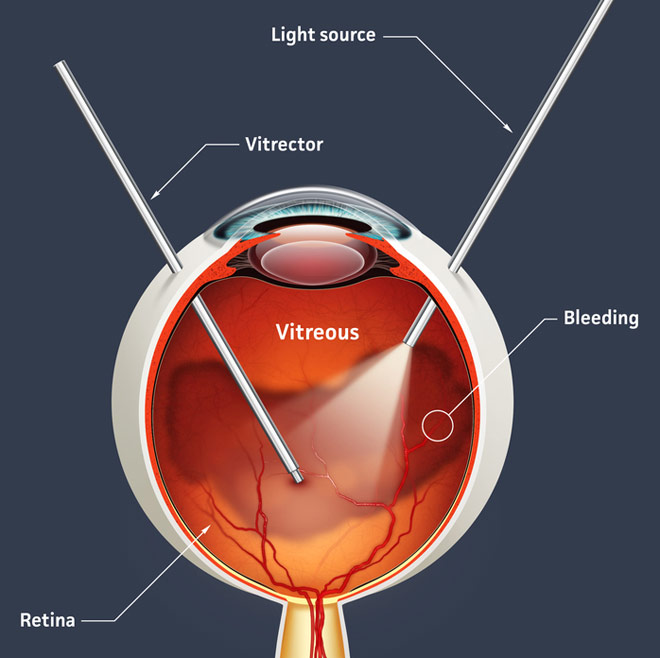

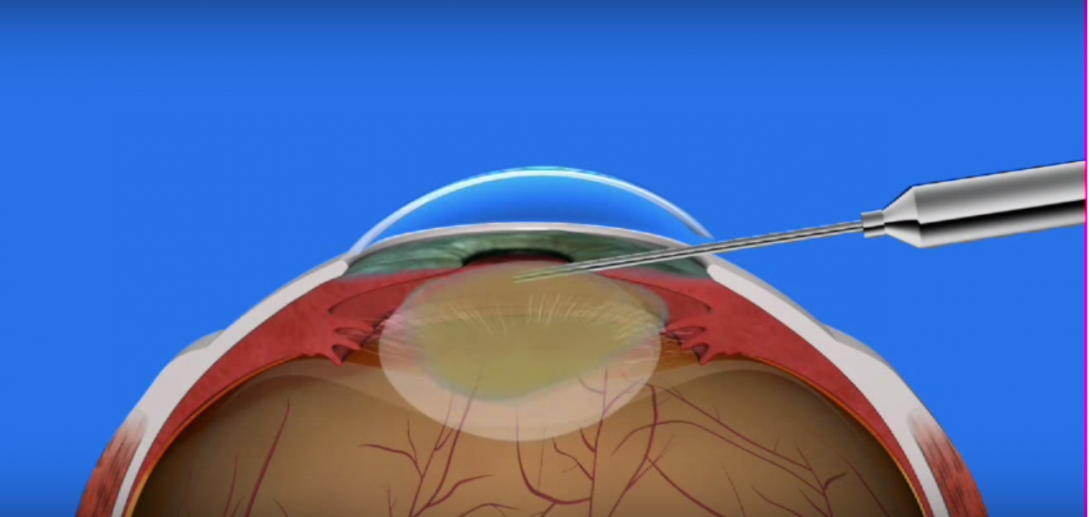

The next day my group and I had to go to UIC surgery to view different ophthalmology surgery that was taking place. I have never observed any sort of surgery, so I was looking forward to this. My group got a little lost inside the building, but we eventually found our way to the surgery floor. We got our scrubs and I got to try on scrubs for the first time in my life. They were not that comfortable to be honest. For the next five hours we watched Dr.Tu perform surgeries. He performed mostly cataract surgeries, which is a surgery to replace the lens inside the eye. The very first time I saw the surgery, I was mesmerized. Dr.Tu was very quick with his work and he would use all sort of tools to poke into the eye and replace the lens. While the surgery took place, I just watched the monitor tying to organize my thoughts. It was very interesting to say the least. Each surgery took about fifteen minutes and Dr.Tu performed six cataract surgeries. After the first couple of surgery it started to get repetitive, but it was still exciting to see how thing were done. At the end my feet were exhausted from all the standing, but I got to experience something that most people never get a change to see live.

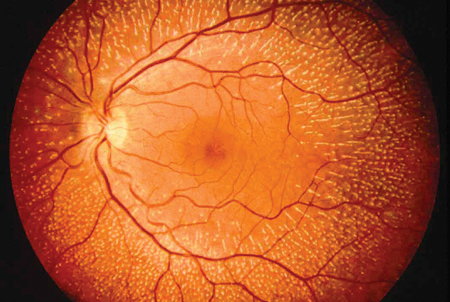

The last day was a half-day, thank god. I was pretty tired from the entire week. I was placed into the department of retina with one of my group members, Sarita. The doctor we were shadowing that day was Dr.Chow and he was also very nice. It was a very busy day, so Sarita and I just ended up followed Dr.Chow around different rooms as he took on many patients. We got to talk to him only when he was done with a patients and it was only for a few minutes. There isn’t much to say about this day because it was very busy at the clinic and we did not want to get in the way of Dr.Chow. We did get to observe how Dr.Chow handled various situations in an orderly and timely fashion. This skill is very useful in the medical field. After the clinic was over Sarita and I met up with our other two members and we did a debriefing of our week.

The first week was very fun and informational and I look forward to the rest of the internship and blogs.

Week two

Kushal Basnet Blog

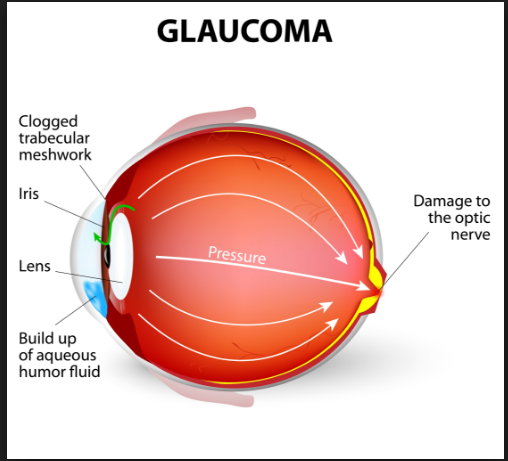

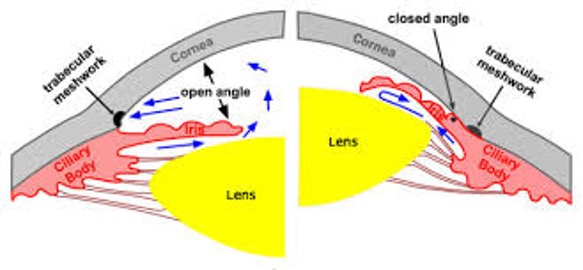

I was placed into the department of Glaucoma for my first day of week two. Glaucoma is damage to the optic nerve of the eye mostly due to high eye pressure. Dr.Sugar informed me that he did not have a set doctor for me to shadow in Glaucoma, so I basically had to walk around till I found a physician on duty. This was a daunting task because it was lunchtime and most of the physicians were out. I eventually came across Sofia, a technician, who allowed me to shadow her until one of the physicians was available. She was a bit skeptical about me after I introduced myself and told her why I was there, but she warmed up to me and was very willing to answer my questions. I asked Sofiaif she could identify any problems that she encountered in a day-to-day basis and she just started listing them all off. She was having problems with the slit lamp next-door, problems with her patients, and many more. I had only shadowed physicians before this point and after having met with the technician, I realized that talking to multiple personal, and not just the primary physician, can lead to better understanding problems that occur in and around the hospital.

After Sofia left, I started to shadow Dr.Wilensky and he was just as enthusiastic as Sofia about letting me know the problems he had. I didn’t want another long list, so I tried to limit my questions by asking him only his main problems. Surprisingly, patient compliance was a big problem. I wouldn’t think that placing eye drop was a big problem, but I guess it was. Many of the patients did not follow direction about the medication they were given, even when the instructing were clear. Dr.Wilensky said that as much as 40 t0 50 percent of the patients were not compliant and their recovery took a hit because if this. I spent rest of the day just following Dr.Wilensky around the clinic. I ended up with a long list of problems faced in this clinic and I was ready to come up with solution for each of them.

The following day was much more exciting than the day before. I was in the general eye clinic with Dr.Sugar. That day in the clinic was particularly slow because the old residents had left and the new residents had come in, so the front desk did not schedule many appointments that day. Dr.Sugar was doing a simple laser eye surgery today and I was really excited to see how that procedure worked. Unfortunately the machine was having a problem and we had to wait for the technician to come fix it. After an hour or two the technician found the problem to be some loose wires in the machine. I was a little surprised to see that such a small thing could lead to a big problem and that there wasn’t some notification on the machine letting the user know what might be the problem. After the laser was up and running, Dr.Sugar proceeded to use it on a patient. It was a fascinating process to observe. The laser was literally poking very tiny holes in the eye to remove small tissue. The patient didn’t feel and thing and the whole process took about 5 minutes. Dr.Sugar even let me use the machine to poke microscopic holes in a piece of paper, which was very cool in my opinion.

I identified many problems on the first two days of week two and I am looking forward to the rest of the week.

Code Blue

Kushal Basnet Blog

The OR is much different in real life than it is in the movies or T.V shows.

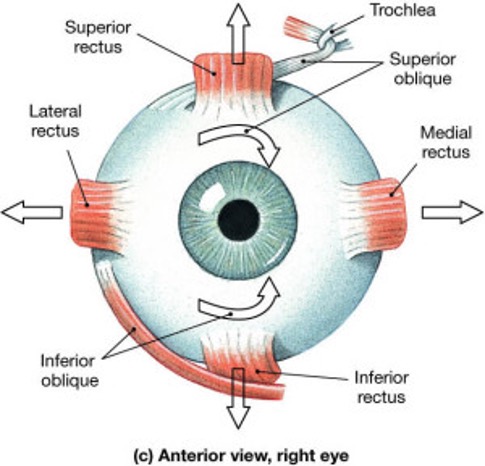

Dr.Sugar had made arrangements for our group to visit the OR this week. He wanted us to watch some pediatric ophthalmology and retina surgeries, so we can get the full scope of the department. We had gone to the OR last week, so it wasn’t anything new. My group didn’t get lost this time around and we made it to the surgery we were suppose to watch. The surgery that was about to take place was a Strabismus surgery, which is a surgery to fix a cross-eye or lazy eye. This was a routine surgery and the primary surgeon had done many, so it wasn’t very difficult for her. This operation was a two-man job, so there was another surgeon assisting with the surgery. The surgery started off great. The primary surgeon was singing along to a song that was playing and even teaching the resident how to perform the surgery. I was fortunate enough to get a spot right next to the primary surgeon, so I could see the full scope of the surgery. All the other surgeries I had seen were on a monitor, so this one was different experience for me. It was very strange watching someone dig into the eye with multiple tools and take things apart.

It was all very calm until the middle of the surgery. The primary surgeon heard a gurgling sound coming from the patient and asked the resident anesthesiologist to check to see if all the vitals were stable. As the anesthesiologist was checking the heart rate of the patient started to increase and the breathing stated to go down. The resident anesthesiologist realized that something was wrong and yelled at the nurse to get his primary attending. A code blue, which is an emergency, was called from the nurse and the room started to light up.

The patient started to flat line, so the primary surgeon and the other surgeon immediately stopped what they were doing and moved away from the patient. Ophthalmology surgeons are not trained to handle emergencies, so stepping away is the best option for them. Within seconds the room started to flood with other doctors and nurses. I made my way to a corner to get out of the way and was called out of the room by one of the doctors. The tension in the air was very high for the first few moments, because all the physicians didn’t know what was wrong. I was outside of the room and had no idea what was going on, but after a minute I could feel the tension fade away. Some of the physicians came out the room and the code blue was called off. It turns out the patient somehow was unable to breath during surgery, so his vitals started to drop. Thankfully at the end of all of it the patient was fine and the surgery was a success.

Something that I found interesting during this while situation was that even though the primary surgeon was a trained physician, there are times when even they must step away. Another thing to notice was the sheer amount of people that flooded the room after the code was called. I don’t know much about emergencies like this, but it seemed like there was more people in the room than that was needed. Most of the people were watching while a few were trying to fix the problem.

This week in the OR has been an eye opening experience and I still have another 4 weeks left to learn.

Second Last Day

Kushal Basnet Blog

Things have slowed down dramatically in the last week of this rotation. Most of the doctors in the Ophthalmology department are on vacation, so it is hard for Dr.Sugar to schedule us in with different departments. Thankfully I ended up getting placed into the Contact Lens and Oculoplastic department for this week.

I learned many things during my stay at Contact Lens. I shadowed Dr.Joslin, who was very friendly and was willing to answers any questions I had. That day I saw about 8 patients and gathered useful information from my observations. One of the patients that I observed didn’t find his new contact comfortable, but was willing to comply for the better vision it provided. The balance between comfort and function is an important aspect of engineering. After seeing this patient give up one for the other, it got me thinking about how many other patients have to do the same. Another patient that I observed was misinformed or not educated enough on how to put on his contact, so his contact ended up falling out and eventually broke. The lack of patient educating seems to be a prevalent theme in the hospital. It is mostly due to patient compliance, but there are certain cases where the patient really wasn’t informed on what to do. Coming up with solutions, like having a video instruction for each medication, could be beneficial to every aspect of the hospital. The rest of the day I observed many more cases and took notes of all the useful information that I could use to write my final report.

My time at Oculoplastic was more relaxed than Contact Lens. Raahil, who is a member of my group, and I were with Dr.Setabutr for most of the day. He was very intelligent and insightful on the problems he had. He was very busy so Raahil and I just sat around for most of the time, but every once in a while Dr.Setabutr would let us tag alone. One of the patients he was seeing that day had chronic muscle spasms in her eyelids, so she had to get 9 Botox shots around each eye. The patient also had to get those shots every 4 months. Raahil and I discussed potential ways we could help the patient. One thing we came up with was to create some sort of a device that has all the shots preloaded and with multiple ports. This way the patient only had to get one shot. We then spend the rest of the day identifying many more problems and trying to come up with solutions for each one.

I only have a couple of more days in this rotation and until it ends I will try to identify many more problems.

Overview of my first rotation

Kushal Basnet Blog

The past 3 weeks in the department of ophthalmology has been a great and fun experience. I learned various amount of things like the primary devices doctors use to examine the eye, how the hospital functions from an internal standpoint, and how surgeries operate. All of the doctors that I worked with were intelligent and they were excited to have me there. I got to experience things that most people will never get a chance to do.

The first week was a bit chaotic. I had never been exposed to the clinical environment, so I was very nervous going into the rotation. I started off in the Department of Cornea with Dr.Sugar in the first week. Dr.Sugar turned out to be one of the best doctors I have ever met. He was very helpful and very willing to answer any questions I had. He let me observe all the patients that he examined and taught me many things. Most of them were from the medical perspective, but he believed that learning things from the medical side would help me better understand the problems from the engineering side. The first week I also visited the OR for the first time in my life. As the days progressed through the first week, I adjusted better and better each day. I got used to being in clinic and by the end of the first week I had lost all of the nervousness that I came in with.

The second week was when I learned the most amount of information and identified the most amounts of problems. I was placed into the departments of Pediatric, General eye clinic, and Glaucoma. I gathered copious amounts of information from physicians and patients. Most of the problems had to do with ergonomics and patient flow. The devices that the physicians used were very staining to the body, which can lead to many physical problems in the future. Most of the patients complained about the wait time, but this is a universal problem. Things also got a little hectic in the OR. I witnessed a code and realized how stressful the hospital environment is.

The last week of this rotation slowed down by a lot. Most of the doctors were on vacation, so it was hard to be placed into a department. I still got to shadow doctors and see many more surgical procedures though. This week was more for reflection and analyzing the problems that I identified the first two weeks. Trying to sort out the main problems from the sea of problems to write in the report was the hardest part of this week.

Just when I thought I was getting in the hang of things, I will be placed into another rotation. The past 3 weeks went by fast and hopefully my next rotations will be good as this one.

Emergency

Kushal Basnet Blog

The Emergency Department (ED) at UIC is nothing like I was expecting it to be.

The first day started of with Dr.Gehm giving us a tour of the ED and I was overwhelmed by the amount of problems I saw during the tour. There were many small problems like, random carts and wheelchairs blocking the path in the hallway, random noises that seem to be going off for no reason, and many posters and signs on the walls. The structure of the department was not well organized. The hallways had sharp turns and not enough room for the gurney to comfortably move.

There were also some big problems like the supply cabinet in the hallway having a broken lock. The supplies in the cabinets were not properly organized and some of them were not properly sealed. During the tour Dr.Gehm mentioned that the lock had been broken for 6 months and they have even caught people trying to sneak supplies out. This shocked me because this problem is huge and it has a simple solution, but no one is trying to fix it. Another problem that was overwhelming was that most of the devices used in the emergency department was either outdated or broken. Some of the equipment were even ducked taped or had exposed wires.

The second day was a little different. Sara, my partner, and I decided to do a night shift to experience the full scope of the department. We started off talking to Dr.Lin and it turns out she is working on a medical device herself. She is trying to make a small device that can plug into any phone and it would take various vitals of the patient. The patient would use this device and then it would be relayed to their heath care provider. This idea was very interesting and I could see the usefulness of this device in the ED, where having a small portable vital reader would make a big difference.

Sara and I then went around the department to ask the staff about the problem they encounter in the ED. I will provide a list of complains below.

- · Lights were too dim. It was very hard to see the vain sometimes for IV

- · The room were too small and they didn’t provide privacy to the patients

- · There was too much noise and that could lead to noise fatigue

- · There was no place to hang the cords for the devices

- · The computers were old

These were just some examples of the complaints we got. Figuring out the good problems from the sea of problems will probably be the biggest challenge of this rotation.

The First Week of ED

Kushal Basnet Blog

The first week of ED was very interesting to say the least.

I had to move around quite a lot in the Emergency department, unlike my first rotation in Ophthalmology. It got pretty confusing at times on where to go, because there isn’t one physician Sara and I follow. We sort of just bounce from one physician to another while they go in to see a patient. We saw many patients this week and each of them had their own set of problems. Whenever I got the chance to talk to one of the patients, I asked them what sort of problems they encountered while they were at the ED and made a list.

- · Wait times. This was a big one and almost everyone said this

- · Space too small or not enough privacy

- · Beds were uncomfortable

- · Place was dirty

- · The lights were too bright or to dim in some rooms

- · There was too many annoying sounds

Sara and I also went around talking to the nurses on Thursday and asked them if they encounter problems. There were a lot of complains about how most of the equipment didn’t work. One of the nurses mentioned an interesting problem that caught my attention. Apparently a trend started at UIC ED a long time ago where when the nurses would draw up a patient blood, they would draw 1 or 2 more tubes than needed. This was done incase one of the primary tubes were lost or something. The nurses were suppose to leave the extra tube of blood on a tray in the room, but a big problem is that the tubes would always go missing or the nurse would place the tubes in random locations. So if you walk around the ED you would see random tubes of blood everywhere.

One of the other nurses was very adamant about how dirty the ED was. When Sara and I went to asked her to identify her main problem, she instantly said she couldn’t stand the filth. She talked about how many of the machine or chairs were full of dust. She told us about how many bugs or insects were in the lights or how all the curtains in the ED were never washed. At the end of her long rant she told us to just take a walk around the ED and look at how unclean the place was, so Sara and I did so. We did notice all the trash and dirt that was in the ED and we were shocked by the state of the curtains in the ED. There were many curtains in the ED and most of them were used to act like walls. We could see the amount of dirt that was accumulated on the curtains from use and we understood why the nurse was so adamant about the sanitation of the ED. If I were a patient in the ED I would have noticed the lack of sanitation and would have been very uncomfortable.

I identified many problems in the first week and hopefully the next two weeks will be just as informational.

Ultrasound

Kushal Basnet Blog

There really isn’t much to talk about from the first two days of this week. Sara and I were only at the ED for a couple of hours on Monday and we took the morning shift on Tuesday. It seems like the morning shifts are usually quiet, but there is an unspoken rule in the ED where no one talks about the ED being quiet or slow because of some superstition all the physicians seem to follow. It’s actually rather funny.

Sara and I did spend a considerable amount of time following one of the resident and a fourth year medical student, who were doing a ultrasound rotation in the ED. The ultrasound machine is often used in the ED because many patients come in with some type of a pain that was caused by impact and the ultrasound machine can be used to check for internal bleeding or damages to an organ. There are two ultrasound machines in the ED; one is new and one is not so new. Most of the physicians prefer the old machine for some reason. I speculate it has to do with comfort of using a machine that the physician has always used. The machine itself is rather old, dirty, and has a lot of cords and probes attached to it. However, the machine is decorated with lots of stickers and even bedazzled, so I guess it makes up for it.

We saw the ultrasound machine used many times this week. Every time the machine was used on a patient the resident would start off by scanning the patients bar code, then he would type out his name and the name of the attending on duty. The resident would have to do this every time and it didn’t take a considerable amount of time, but it did seem like a hassle. I noticed several things during our observations and made a list.

- · Lots of gel is used during the ultrasound examination. The gel would get all over the patient and would be wiped away with a towel at the end

- · After the machine is used, the resident would wipe down the probe with a sanitizing towel.

- · There was a basket that had many empty tubes of gel on the ultrasound machine.

- · Most of the wires hang out of the machine and it didn’t seem like there was a place to hold them.

- · The buttons on the machine were hard to press.

- · The probes are uncomfortable to the patients at times.

- The machine would have to be plugged into the wall after every use

I’m sure most of these problems have to do with budgeting and there are better ultrasound machines out there, but there doesn’t seem to be any direction on sanitation or maintenance of the machine. It’s hard to tell if that’s the physicians’ job or someone else.

One of the attending set Sara and I up with a bio-engineer that works at the hospital on Wednesday, so I am looking forward to that. Hopefully that will be informational and I will have more stuff to talk about on my next blog.

Bioengineering

Kushal Basnet Blog

Sara and I spent the whole Wednesday of this week with Sergio, a bioengineer that Dr.Kotini set us up with. We had some issue finding him at first because we didn’t know what he looked like and he didn’t know what we looked like, but we did end up meeting up. Sergio started the day by taking us to his office on the 7thfloor of the hospital.

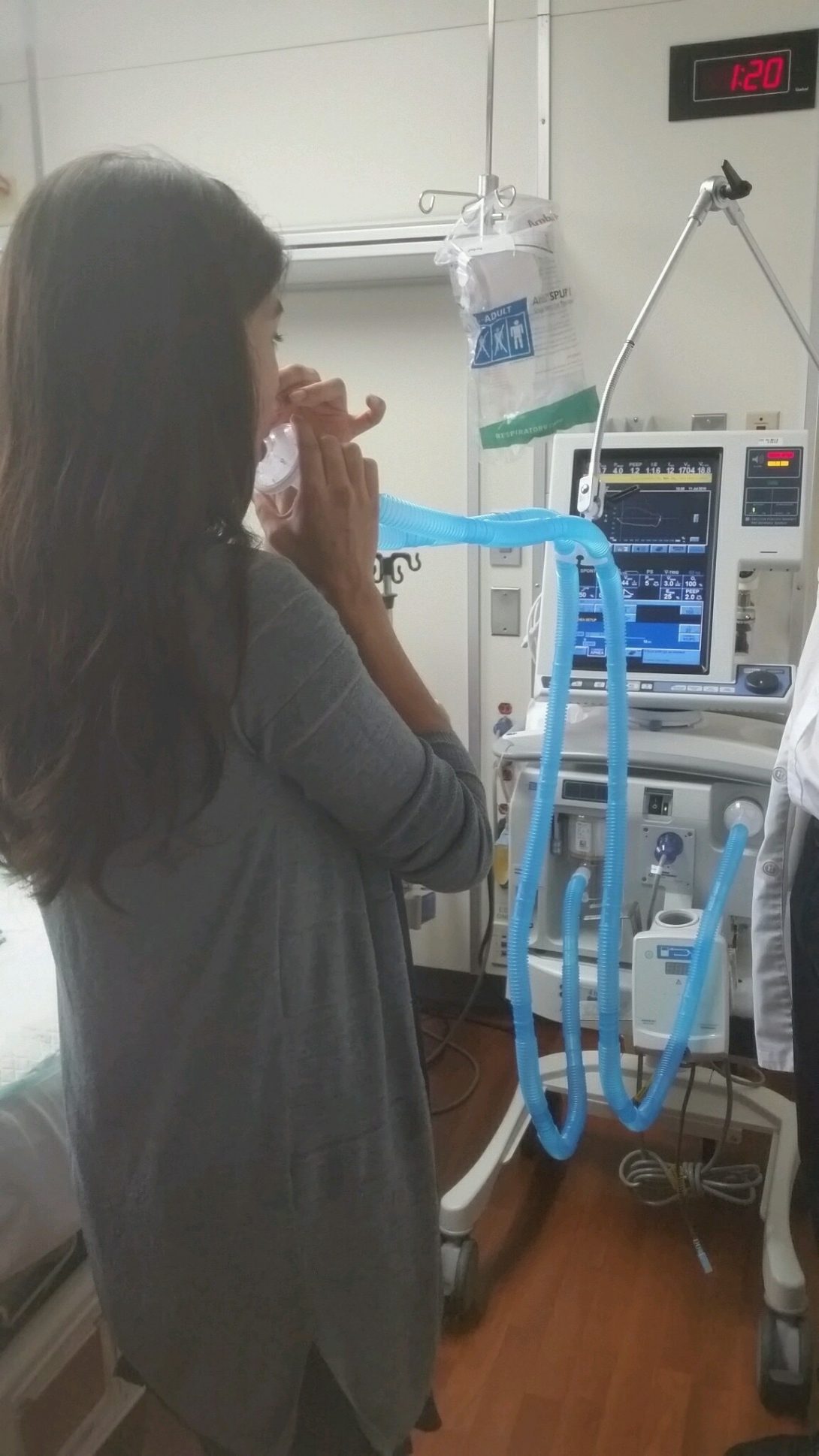

His office was very interesting, because it actually looked like an engineering laboratory and not a hospital room. There were many broken devices and many tools that were used to fix the devices. Sergio sat us down and explained the many things he does in the hospital. He told us that he is in charge of fixing many of the broken devices in the hospital, but he is also an on-call engineer, so whenever a device breaks down and requires an immediate fix he will be called in to fix it. Even though he fixes many of the devices in the hospital, he is mainly in charge of the anesthesia machine used in the ORs.