Students: Part 1

Najah Ahsan

Najah Ahsan

My name is Najah Ahsan and I am a rising Senior in the Bioengineering Department at the University of Illinois at Chicago with a concentration in Cell and Tissue Engineering. As a Bioengineer, I am committed to apply my knowledge and experience in developing products that can improve the quality of life of people. It is imperative that engineers not only be able to design products efficiently, but also understand how each product functions in the environment for which it has been developed. Therefore, it is very important to understand the needs of physicians, patients and others involved in the treatment process for successful implementation of a medical device. The Clinical Immersion Program is an unique opportunity to observe clinical environment, participate in discussions with physicians, patients and other caregivers, and observe surgical procedures. The hands-on experience involving examination, diagnosis, and treatment provide insight about the needs of physicians and patients, and the participants gain invaluable knowledge about concerns that encourage them to start thinking about potential solutions. Please feel free to send me an email if you have any questions about my blog. Thank you!

Najah Ahsan Blog

Najah Ahsan Blog

Introduction To Program – First Few Days

Najah Ahsan Blog

The first few days of the Clinical Immersion Program have been wonderful. On the first day, I met the other members of my group (for the Pulmonary Critical Care rotation) and we were all introduced to the specific details regarding the program. We also went through a presentation discussing user-centered medical device designs. This was defined as being “an approach that brings the user’s needs into consideration at every stage of the design process of the project”. We also discussed how user-centered design and medical device development were different and that a good user experience could be reached at the intersection of technology, business, and human values. In order to better understand the design approach, we reviewed a case study about infusion pumps and answered the following questions in teams: “What is the systematic problem that needs to be addressed?”, “Who are the users?”, “What are the shortcomings of the existing design?”, and “How will the device be used?”. After lunch we went through fun exercises to bond as a group and discussed the aspects of the program that we were excited for and the parts that we were nervous about.

Najah Ahsan Blog

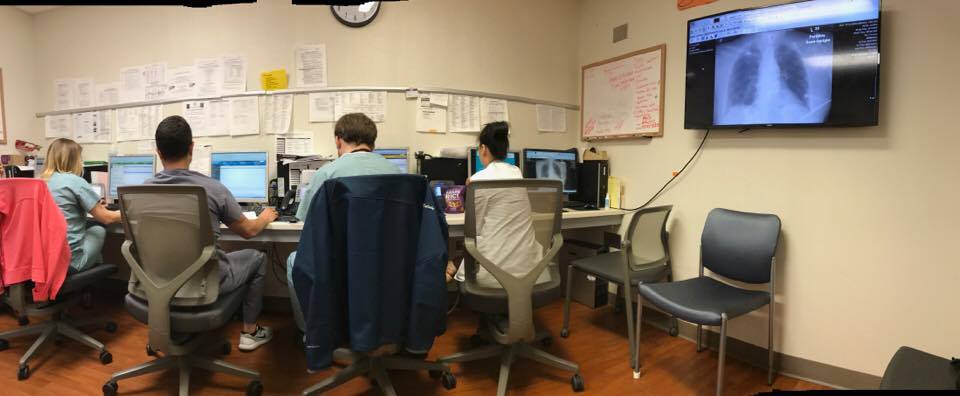

The rest of the first week in the Clinical Immersion Program has been very eventful. On Thursday (June 1, 2017), we went to visit the Pulmonary Hypertension Clinic. Initially, the team and I sat in a room where the Attending Physician (Dr. Machado) and fellows discussed patient symptoms and care plans. There were computers in the room for accessing patient information and monitors for viewing images. We were shown a patient’s CAT Scan of lungs (images showed heavy scarring) and then accompanied Dr. Machado when he went to check the patient. During the visit, we learned about a technique that is used to test for pulmonary hypertension called cardiac catheterization. It measures pressure in the lungs and can lead to a diagnosis of the condition. In addition, we learned that pulmonary rehab is an option for patients to strengthen their lungs. The physician mentioned that cardiac catheterization is preferred for diagnosis purposes because echocardiograms can be incorrect when determining the pressure levels in the lungs. Next, we went to visit another patient who had completed a six minute walk test earlier. The physician pulled up the patient’s previous records on his computer and compared with the most recent results for discussions. The third patient that we visited suffered from a rare condition called scleroderma and also suffered from pulmonary hypertension. It was explained to us that scleroderma causes hardening of the skin (texture becomes leathery) and arteries. Having both scleroderma and pulmonary hypertension is very rare. We went on to observe the visits of two more patients and observed the checking of their pumps and inhaler discussions.

During all of the patient check-ups, I noticed that the physicians were using the computer in the room (every room had a computer) to look up patient history. The patients were asked to sit on beds while getting their breathing checked. During one of the visits, the foot pedal was pressed to control bed position (move the top part forward), but the pedal/bed was not working. So, the physician asked him to raise his legs for observation.

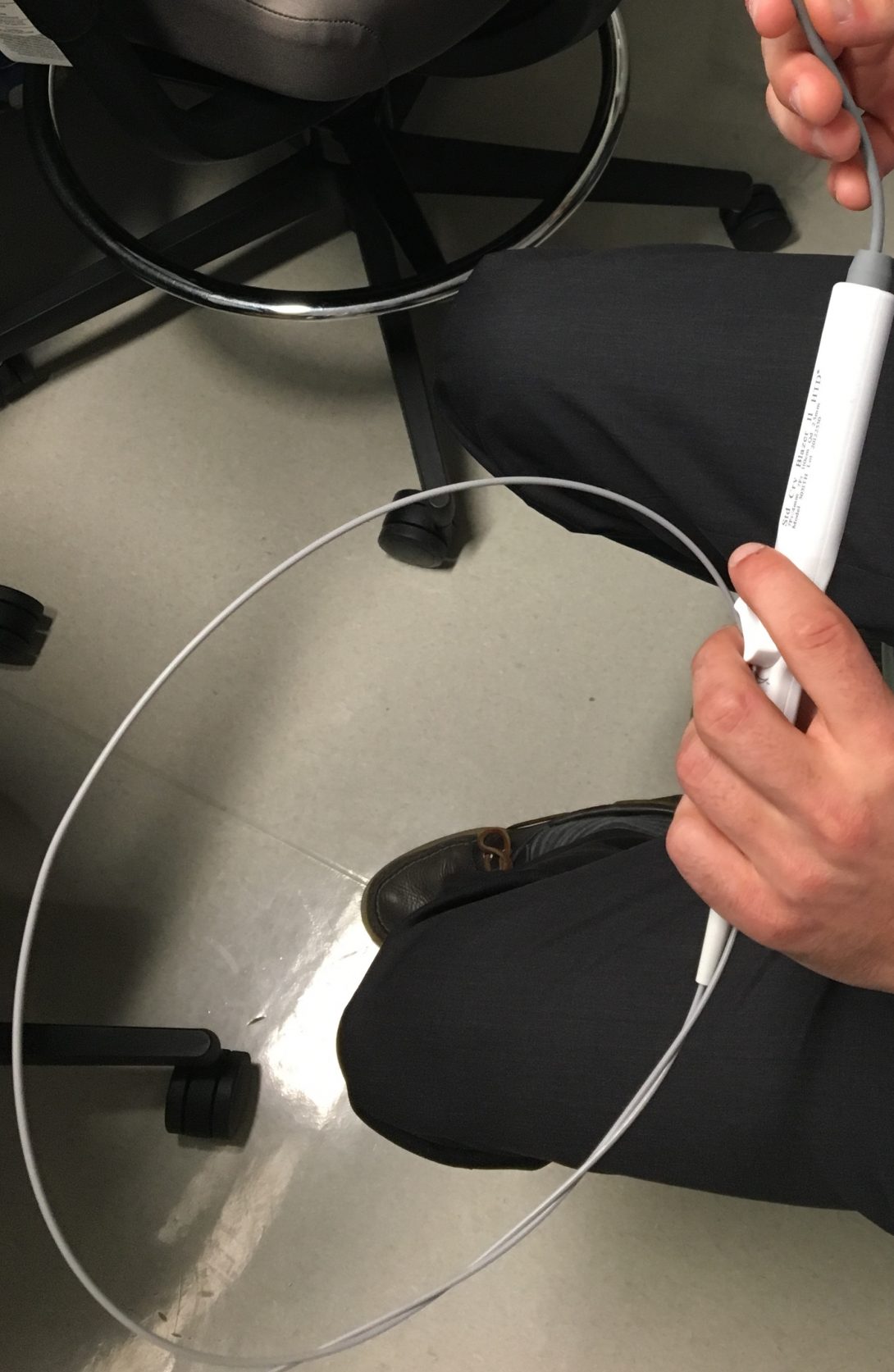

For the second part of the day, we went to the PFT (Pulmonary Function Test) Lab. The technician was using various machines to test the impact of a patient’s asthma medication. The software automatically converted the units of the measurements (example: inches to centimeters). The first machine was to conduct a spirometry test (patient breathed in and out in the machine) and the software was capable of allowing “good” data from various tests to be attached with the best version of final data. As a result, the technician did not need to conduct tests over and over to get a good overall data set. The second test, the “diffusing capacity test” determined the patient’s lung efficiency. The American Thoracic Society has guidleine for what is considered an acceptable result for this test. A small level of carbon monoxide is used in this test, so the technician had the patient wait two minutes before conducting the next test. In the third test “body plethysmography”, the patient sat on a glass box-type machine and the test run was pressure based. For this machine, the technician mentioned that it would be convenient if the microphone that she used would turn on when she was using the screen (currently she has to turn on the microphone manually). After all the tests ran the first time, the patient used his inhaler and two of the tests were repeated to determine if there was any improvement. At the end of the visit, a printout of all the results were provided to the patient.

The technician said that 10 – 14 patients visit the PFT lab on average per day. She stated that the changes in the health care system has led to a decrease in the number of patients coming in for testing. We looked at the mouthpiece used by the patients for the machines and it was explained to us that the piece had a built-in filter for sanitary purposes. In addition, the first machine had a rapid gas analyzer. In terms of the software, the technician mentioned that the equipment was based on Microsoft, so it was easier to learn about and train others about the new devices. Before our time at the PFT Lab ended for the day, the technician told us that a pre-registration system for patient check-ins would make the process much more efficient and less stressful for everyone.

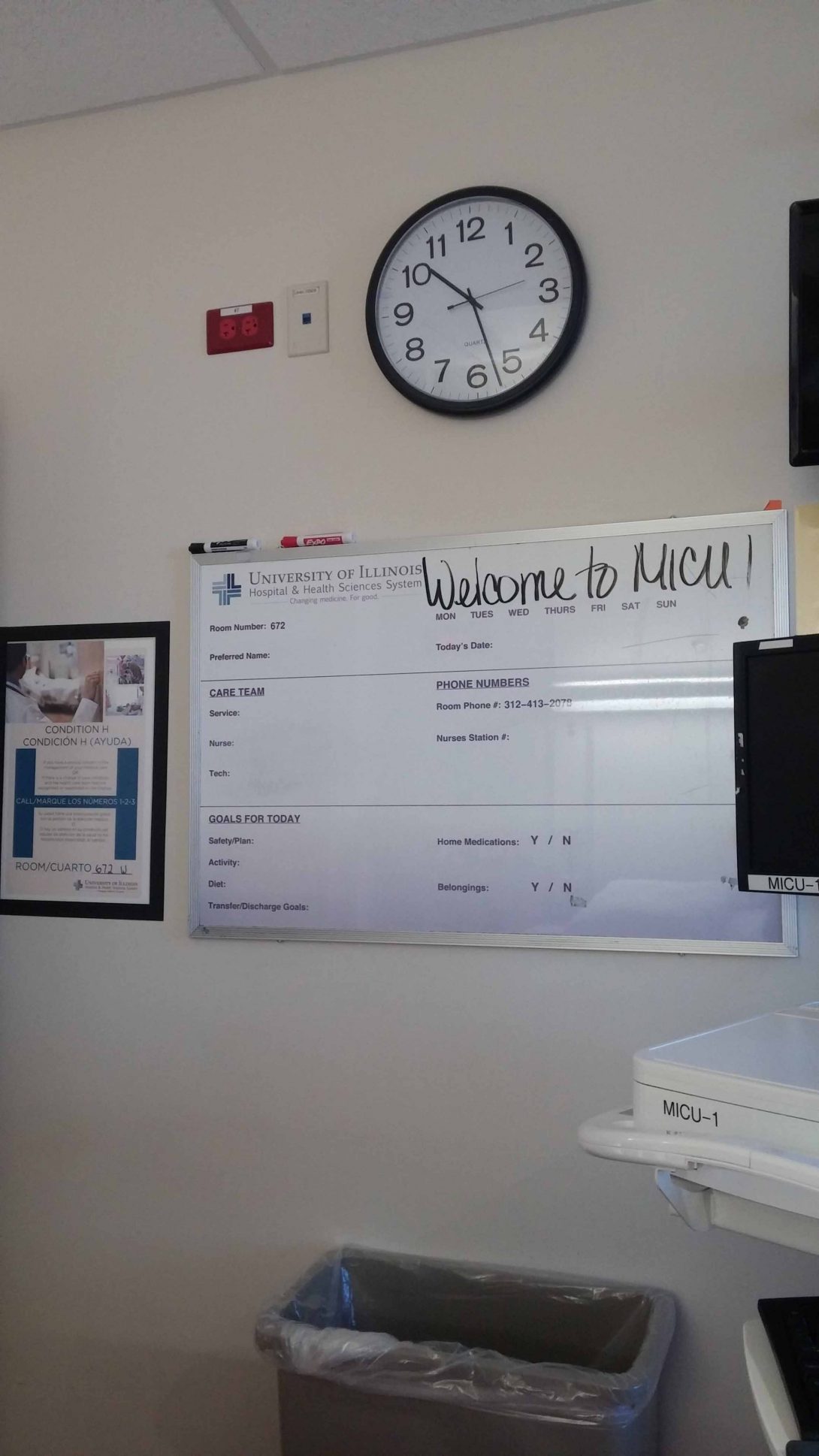

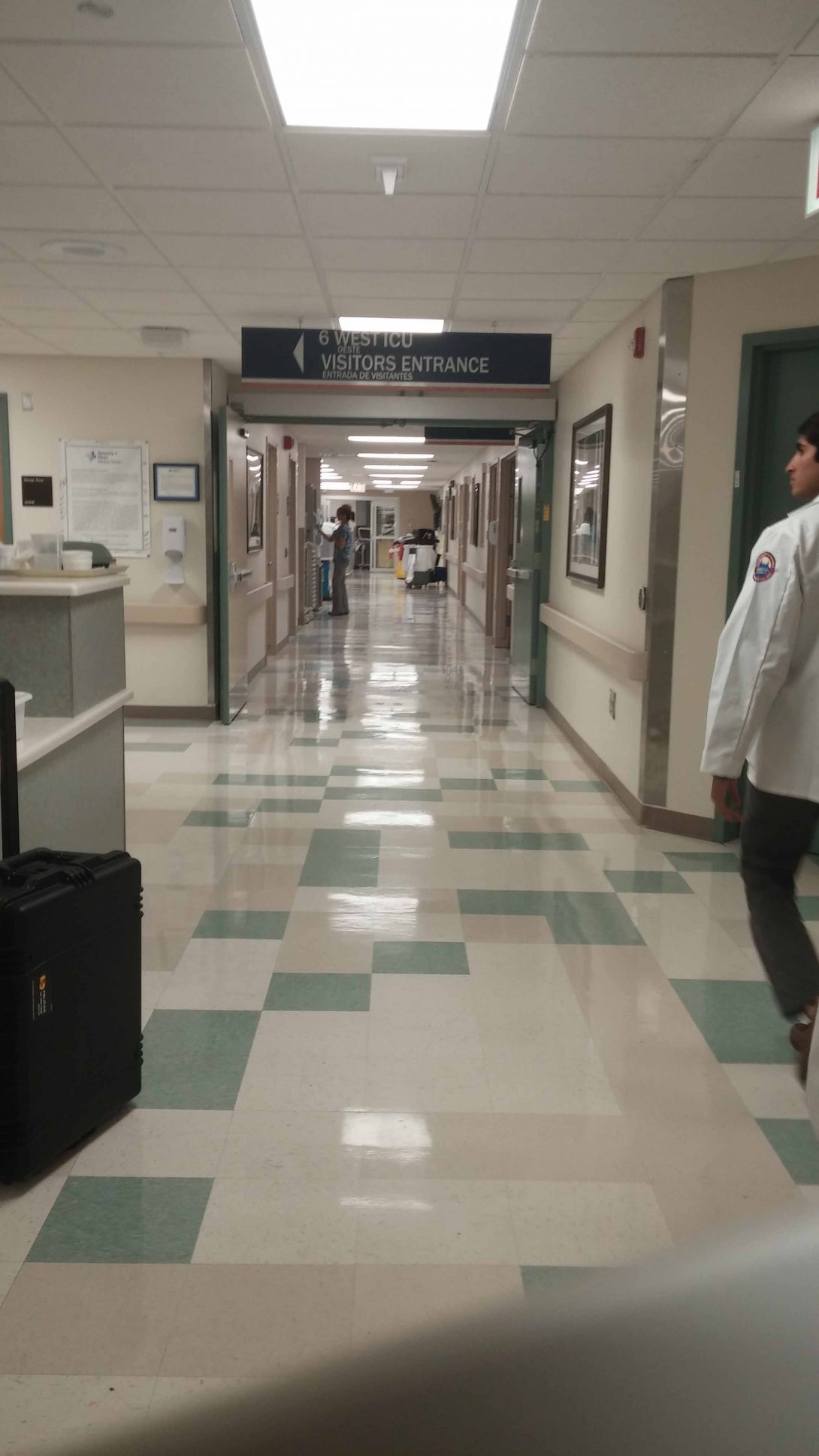

On Friday (June 2), our time was split between the MICU and the Sleep Clinic. In the MICU, we observed the morning rounds. A large group of interns, nurses, and fellows (at least 10 people) gathered in front of the patient room and Dr. Machado listened to the patient details and care plans that were being summarized. A nurse wheeled around a computer and Dr. Machado used a small table to write his notes on. I noticed that those listening to the discussion in front of the patient rooms frequently took notes (everyone was provided a printout of the patient information based on data from 6:30 AM). We went around the floor and the time spent on each patient seemed to vary based on the severity of each case. After discussion, Dr. Machado and a few others would go into the rooms to say hello to the patient. Each patient room had a window, TV and glass doors. Two monitors were placed on the wall for both sides of the floor and had all of the patient heart rate information displayed. The nurses’ station was located in the middle of the floor and the patient rooms were around it. A large screen behind the nurse station had the patient contact status listed (contact, non-contact, etc.) It was a little difficult at first to differentiate the nurses and interns because they were all dressed similarly. After visiting the patient rooms, the entire group went to a room to view the scans of patients on a big monitor. It seemed like they were unable to watch the Echo video because the computer did not have the required software installed. It appeared that the patients were assigned to one of two teams and kept track of that way (in terms of deciding whether they leave or stay in the MICU). Overall, the MICU was fairly noisy and I could hear the phones at the nurses’ station ringing at almost all times. In addition, there were always discussions happening during rounds and various alarms and beeping sounds coming from the rooms.

The Sleep Clinic was a very different environment from the MICU. The office and rooms were very quiet compared to the MICU, and there was much less traffic in the hallways. The clinic runs nine rooms at a time and the exam rooms are used as sleep study rooms at night. Each room has a TV, bed, computer, bathroom and equipment for monitoring the patients. For testing, the EEG, EKG, and EMG wires are connected to a headbox which is connected to a base station.Two patients are assigned to each technician. We met with Dr. Najjar and he mentioned that the Electronic Medical Record was not very good and that there was a lot of room for improvement. For example, it was slightly inconvenient when Dr. Najjar was looking at his schedule, he needed to manually extend the columns to view his whole schedule. Our group of four was split in half and each group went with a fellow. There seemed to be a consistent routine where the fellows would meet with a patient, record new information on the computer in each exam room, then the fellow would meet with Dr. Najjar to discuss the plan. Then the doctor would go to have a conversation with the patient. I thought it was amazing how the sleep studies provided data that helped the physicians accurately diagnose issues like sleep apnea and narcolepsy.

This week was filled with new experiences and I am excited for next week!

Week 2 – Part 1

Najah Ahsan Blog

On Monday, each group gave a presentation about their rotations. It was a great opportunity to learn about their experiences in different environments. Later in the day, we completed an interview activity where we asked a partner to describe their perfect day. The last task on Monday was to use post-it notes to write down our observations and put them on a large white foam board. My group divided our notes into two categories, observations and suggestions, and divided the board into sections based on the various clinics and floors we have visited. I know this method will be extremely useful to maintain our notes in a more visual way.

On Tuesday morning, we visited the MICU. I could immediately tell that the group going through rounds was smaller than the group we had seen last week (it seemed like only Team 2 was doing rounds with the Attending Physician this morning). This allowed the group to move more quickly from room to room. All of the team members were once again taking notes on their patient sheets. This practice caused me to wonder if using technology such as iPads or tablets would make referencing patient sheets and note-taking easier. Some of the rooms being entered were “Contact Plus” rooms and I noticed that each of these rooms had a chest with gowns, gloves, masks and disinfectant wipes. The individuals entering these rooms would discard these items in the trash inside the room. Also, there were stethoscopes hanging above the beds in these rooms for physicians to use. I noticed that those entering the patient rooms carried a blue mask with them from room to room(some had it wrapped around their elbow). After rounds, we looked at the scans on the big monitor in the room where Team 2 sits. While talking to the Attending Physician and the Pharmacist, we learned that a new system that connects the electronic medical record to the infusion pumps will eventually be introduced to the MICU. The system will allow infusion pumps to control dosages automatically based on values changed in the record. This will help prevent medication mix-ups and human error in dose control. The Attending Physician also made an interesting prediction, stating that with the way that ultrasounds are used to get information, the stethoscope may eventually be replaced with hand-held ultrasounds. The last procedure we observed was a Diagnostic Thoracentesis where fluid was being drained from around the lung. An initial ultrasound was important to complete to get a good visual on the area so that the resident and fellow could avoid hitting an artery. The needle being used for the procedure was blunt to avoid puncturing the lung.

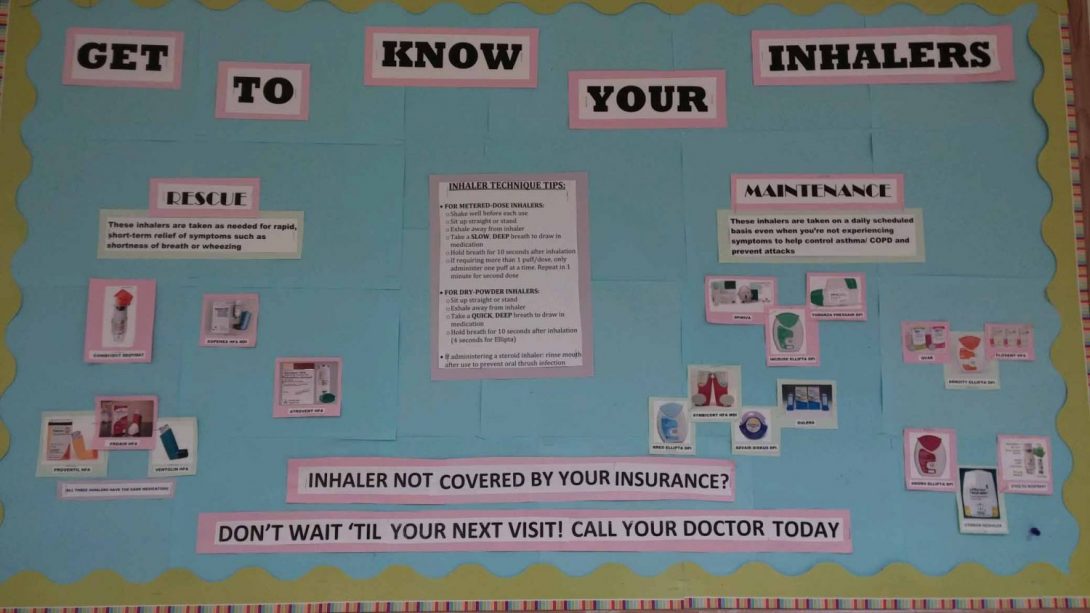

The second half of Tuesday was spent in the Pulmonary Fellows Clinic. The first patient we visited mentioned that her oxygen tank was inconvenient for her to carry. Unlike the oxygen tank that could be rolled around, the patient had to carry the smaller tank in a side bag. The patient also mentioned that the oxygen tubes got tangled fairly easily. Overall, it seemed that inhaler discussions were the most common in the clinic. A major issue that the Nurse Practitioner told us about was that many of the patients mixed up their inhalers (they would exchange the controller and rescue). In addition, she mentioned that it was important for patients to understand that they need to take care of their heath consistently. I noticed that a lot of documentation was involved in the patient care process (seemed that just as much time was required for documentation as for the patient visit), and the physician mentioned that these requirements were being increased.

On Wednesday, our time was split between the Pulmonary Function Testing Lab and observing procedures. We visited the other PFT Lab and it was smaller than the other PFT lab room. There were fewer piece of equipment, so there was enough room for the technician, patient and our group. The technician was running the same tests that were done last week (spirometry, diffusion capacity, body plethysmography, etc.). In this room, instead of using two different machines for the testing, only one was used (door for the Masterscreen Body Device was left open for first part and closed for the second part). The technician explained the tests as he did them and also stated that he has to adjust the ambient conditions for calculations and calibrate the machine every morning. This device is older than the one in the other room and does not have a sample tubing component. In the afternoon, we observed a bronchoscopy (BAL) where the physicians wanted to check a small nodule in the lungs. The tip of the scope for this procedure was able to move up and down with a button, but the doctor needed to physically turn the device if they wanted to move it left or right. The scope itself had a lens and another part that could take in and shoot out liquids (such as saline or numbing medication). The physician and technician mentioned that one of the other scopes, the EBUS bronchoscope (utilizes ultrasound), was leaking. As the department only has one EBUS scope, all the procedures using the device needed to be rescheduled.

Week 2 – Part 2

Najah Ahsan Blog

The majority of time on Thursday was spent in the Pulmonary Hypertension Clinic. Each patient visit consisted of a visit from the Pharmacist, Fellow, and both the Attending and Fellow. When talking with the Pharmacist, we learned that she goes to talk about the medications with the patients and tries to make sure that they know how to take them correctly. She follows a template so that she is able to maintain ten minute visits with each patient. When looking up patient information/records, the Pharmacist mentioned that it is much easier if they get all of their care at UIC (as records are easily available). The last patient of the day required a translator and the Fellow used the phone located in the exam room to call an interpreter. The interpreter translated for both the patient and physician and was heard via speaker. Overall the call worked, but I noticed that it was a little bit difficult to clearly hear what the interpreter was saying because of background noise coming from his office.

On Friday, our first stop was at the MICU. During rounds, the Residents, Interns, Nurses, Fellows, Attending and Pharmacists discussed the patient care plans for each patient. The Clinical Pharmacist made an announcement to the group about a new Nanosphere DNA Detection device in the Microlab that could be used for testing patients. We also observed the ventilator system and an ultrasound being conducted on a patient. The ventilator is an important part in Pulmonary Care and uses positive pressure for treatment (as opposed to the negative pressure the body uses for breathing).Within a few days, the ventilator system can cause issues for the patient.

In the afternoon we went to the Sleep Clinic. We were given the task of obtaining background information about the patients, their reason for the visit and completed the Epworth Sleepiness Scale form with them. We asked patients about their sleep schedules, snoring, breathing, etc. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale is a form with a series of scenarios that the patient ranks from zero (would never fall asleep) to three (high chance of falling asleep). The total score helps the physician evaluate their tiredness. After gathering the information, we reported our notes to the Fellow, who then went to see the patient for their exam. It seemed that the patients liked talking to us. This was a great experience and I enjoyed being to talk to patients and listen to the physician use the information to find a plan to help them.

Week 3 – Part 1

Najah Ahsan Blog

On Monday we listened to the presentations given by each of the groups about their rotations. It was interesting to hear about the patterns and issues that they were all observing. Everyone seemed to have a great time observing the surgeries and learning about devices that were being used. Afterwards, we learned about the components of a need statement and reviewed examples of underdeveloped and revised statements. Lastly, we went back to our observation boards, added more notes from the week, organized our post-its by category and wrote a few need statements for Pulmonary and Critical Care.

During our time in the MICU, we focused on asking the residents about ICU delirium. They stated that ICU delirium can occur in patients when they have been in the hospital for an extended period of time and seems to occur more frequently in elderly patients. The delirium can change on an hourly basis and patients can become especially confused during nighttime. To help prevent delirium, the residents mentioned that it would be beneficial if a good sleep/wake cycle could be maintained (such as by keeping blinds open during the day and closed at night) and patients feel as comfortable as possible (for example, sometimes it is helpful if the patient’s family would bring pictures from home). In the ICU, regulating the sleep/wake cycle is difficult because patients need to be woken up for testing early in the morning to have results for rounds at 8 AM. In addition, the IV poles beeping sound and bed alarms can wake patients up or prevent them from being able to fall asleep. One of the residents made it very clear that benzodiazepines were not good treatment options for delirium. She said that many professionals still used benzodiazepines because they were not well educated on the patient delirium issue and are unfamiliar with the treatment. When patients, especially the elderly, are treated with benzodiazepines they have a higher risk of falling. One of the other residents mentioned that another hospital that he had worked at had signs such as “Call, Don’t Fall” in the rooms and above the patient beds to remind confused patients that they need to ask for help before trying to go anywhere.

During our time in the Pulmonary Fellows Clinic, we went to see patients with both the Nurse Practitioner and Attending Physician. The issues that were addressed in the clinic included possible sleep apnea, problems related to COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease), and sarcoidosis. For the patient with the suspected sleep apnea, the Nurse Practitioner mentioned that the patient would have to undergo a sleep study, but that it would have to be scheduled in two months because the clinic appointments are booked until then. It seemed that this could be related to the fact that the clinic only has nine rooms for the sleep studies that happen each night. One of the other discussions that appeared to be fairly common was the patient wondering which medications insurance would cover. In one of the cases, the inhaler that one of the patients had been taking (that had been benefitting them) had a significant price increase and he could no longer afford to purchase that brand. The physician and nurse told him that they would see what they could do in terms of getting the same medication or maybe seeing if there was another type that they could give him. Needing to check which of the inhalers or other medications were covered by patient insurance seemed to be a consistent part of the routine for the pharmacists and physicians.

We also had the opportunity to listen to one of the Fellows explain symptoms of Pulmonary Hypertension in more detail. To diagnose Pulmonary Hypertension, a right-heart catheterization needs to be done and the mean pulmonary artery pressure would greater than 25. Other tests to be done are: cardiac output, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, pulmonary artery wedge pressure, resistance, and pulmonary vascular resistance. We then learned about the five pulmonary hypertension groups and the risks and test results associated with the conditions. The Fellow later explained that it is important to diagnose Group IV because it is treatable and can be cured. It can be treated through a procedure called a Pulmonary Endarterectomy or a vasodilator (for those unable to undergo the procedure). Group I (Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension) was also further explained to be associated with drugs, HIV, congenital disorders, collagen vascular disease (such as scleroderma), and cirrhosis. It was also surprising to hear that on the west coast, the most common drugs to cause pulmonary arterial hypertension are weight loss drugs. In terms of the pathophysiology of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension, the Fellow explained the associated causes are nitric oxide deficiency, increased endothelin and prostacyclin reduction. The issue with the drugs being used to treat these conditions have not shown to improve mortality. Also, trying to conduct a large study for Pulmonary Hypertension is difficult because it is a rare disease.

Week 3 – Part 2

Najah Ahsan Blog

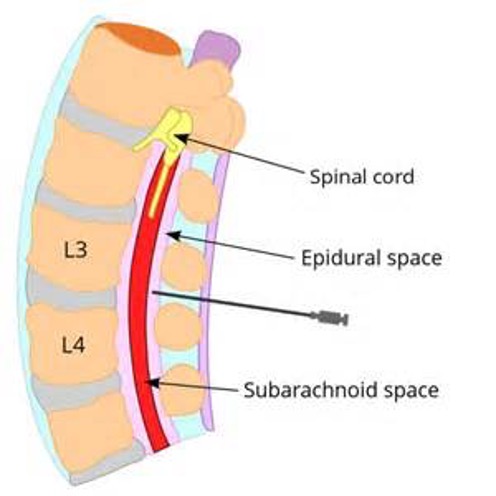

In the Pulmonary Hypertension Clinic, we saw a few patients suffering from various symptoms related to pulmonary hypertension. To fully diagnose and understand the level of pulmonary hypertension, patients need to undergo a test called right heart catheterization. The patients that needed to go through this procedure prior to their visit said that it was extremely painful. One of the patients also said that she had pain in her arm for a couple of weeks after it was done and felt that a few of her fingers were numb for that time as well. This was the first time in the clinic that I had heard patients complain about the pain associated with the test. While discussing with the nurse, we learned that anesthesia is not used for this procedure and patients can experience pain/discomfort.

During one of the appointments, the physician reliance on technology was clear. The patient in the room needed to discuss her recent test results with the physician, however while the physician tried to pull up the records on the computer, the machine turned off. The physician tried to fix the computer but was unable to turn it back on. As a result, he had to go find an empty exam room and move the patient there to complete the conversation. This made me wonder what would happen in the event that a backup computer in another room was not available and felt the need of a contingency plan in case all rooms were occupied. Once the computer dilemma was quickly resolved, the nurse came to demonstrate how to use an inhaler system for Tyvaso (prostacyclin). The nurse explained how to assemble the system and how often to administer the medication.

During our second visit to the MICU for the week, we listened to a presentation given by one of the Fellows about “Surviving Sepsis Guidelines”. We also talked to an anesthesiologist about her work and what she has seen with patients suffering from delirium during her time in the MICU. Similar to our conversation with the other residents, she mentioned that benzodiazepines could negatively impact the cognitive function of the elderly in particular. She also said that getting the patients out of the ICU, bringing family, regulating the sleep/wake cycle and re-orientation of the patient would help decrease the delirium.

The last stop on Friday was at a clinic where we were able to follow the Attending and Fellows for their patient visits. The physicians were extremely welcoming and explained each patient’s condition and scans with us. On the topic of ICU delirium, the Attending told us that when he was an intern forty years ago that the lights would be turned off and the nurses were very serious about making sure everyone was quiet and keeping doors closed so that the patients could rest.

This was an eventful week where we learned quite a bit from our rotation and look forward to the next week.

Week 4 – Part 1

Najah Ahsan Blog

We started off this week learning about the needs that the other groups had identified during their rotations. It was really exciting to see that our weeks of observations have allowed us to identify potential improvement that we could begin to address. Our team initially identified four areas of need related to MICU delirium, patient inhaler usage, physician time with patients, and physician visibility during pulmonary procedures. Although these are all extremely interesting topics, we felt that it would be the most feasible to focus on two topics instead of attempting to address all four of the identified needs. Therefore, our group decided to focus on patient delirium in the MICU and patient inhaler usage. In terms of patient delirium, we would like to find a way to decrease/prevent delirium in order to positively impact the patient’s recovery. For the inhaler use, we would like to educate patients on the proper way to use their medications to allow them to receive the most benefit from their treatments.

The first clinic that we visited this week was pretty busy. There were three Fellows, a Nurse Practitioner and an Attending seeing patients. The majority of patients that I observed had a history of smoking and were visiting the clinic due to issues such as shortness of breath, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome, and asthma. One of the first patient for the day was a first time patient and the physician needed to ask a series of background questions to establish a record for the patient. I noticed that she explained why she was asking each question and how it related to the patient’s care. The physician later explained to me that she did this to make the patient feel comfortable. She said that when asked personal questions, some patients feel that the physician is judging them for their choices and she wants them to know that these questions are necessary and that she makes no judgment and wants to help them. A few of the patients required oxygen tanks, but did not bring them to the office and admitted that they do not like carrying around the tank. the large rolling tanks seemed to cause more inconvenience, but the smaller tanks need to be refilled more often, which is also a source of inconvenience. A patient who were still smoking were made aware of the Smoking Cessation Clinic and offered help to quit. the physicians tried to convince them to stop smoking as it would greatly help in preventing further damage to their lungs. The patient seemed interested in the clinic, but wanted to try to quit by himself before coming back to seek their professional help.

In the MICU, we focused on looking further into the environment and noise levels. The first thing we noticed was the doors to the MICU were wide open. We entered an empty patient room and tried to determine what the patients would hear from the outside. When the door was closed, the noises from the hallway were significantly muffled. In the hallway in front of two empty rooms, we tested how far noise could travel by having one part of our group discuss in a normal tone of voice and the other part of our group walk in the opposite direction and they reported that they could move 15 – 20 feet away and still be able to hear us vaguely. This indicated that patients in the MICU who have their doors open during rounds would most likely be able to clearly hear the physicians and nurses discussing in the hallway. I also noticed that one side of the MICU floor had sliding glass doors while the other had regular wooden doors. The glass door rooms allowed light from the hallway to enter the rooms and had curtains that surrounded the patient bed for privacy. The curtains were not open around most of the patient beds and the doors were kept open in the majority of the rooms. I wonder if there is a reason that the curtains are kept just around the bed and not just in front of the door (seems like it may be easier if curtains were placed in front of the door). The majority of the rooms seemed to have their lights off. It was interesting to see that there were new observations that we were able to make about the MICU environment once we focused in on one particular topic in that area.

I look forward to the rest of the week!

Week 4- Part 2

Najah Ahsan Blog

During the second half of the week, I paid close attention to the environment in the clinic. In the Outpatient Care Clinic, I noticed that the hallway had lots of natural light and the hallways were very wide. There is also seating available in the hallway in addition to the seats in each of the clinic rooms. The clinic room that we visit each week is located in 3C (the Pulmonary and Allergy Clinics are held here). Along the hallway there are multiple clinic rooms/offices and are labeled 3A – 3F. Overall, I noticed that the building was very well organized.

We spoke with one of the Fellows about the topics that we have identified as potential areas for improvement. On the topic of MICU delirium, the physician mentioned that in terms of treatment, he believes that most people should know not to treat patients with benzodiazepines. He also thought that our idea to have family pictures in the patient’s room (to make them feel more comfortable) would benefit the patients. He also suggested we look into the impact of calming music on patient health. When we discussed regulating the sleep/wake cycle for the patients, the physician mentioned that lights are generally turned off at 7 or 8 PM and they are not so good at turning them back on during the day. To prevent noise disruption for the patients, we discussed with the Fellow about the possibility of providing the patients with ear plugs. He thought that this was a good idea, but cautioned that they would need to be visible to the physicians to prevent any confusion about the patient’s responsiveness.

With respect to the need for better patient inhaler compliance, the Fellow mentioned that one of the pharmacists in clinic demonstrates proper inhaler technique to patients. However, the pharmacist is only in clinic on Friday, so not all the patients are able to benefit from their demonstrations. The Fellow mentions that he plays YouTube videos for his patients about proper inhaler technique in their exam rooms while they wait, but he is not sure if other physicians do this. He thought a box to store inhalers would be beneficial (similar to daily pill boxes) and also thought our idea about labeling Controller and Rescue inhalers with a “C” and “R”, respectively, would be very helpful to prevent confusion. We also met with our mentor, who had a positive response to our ideas. He also mentioned that education was important in terms of letting patients and physicians know about the inhalers and delirium issues.

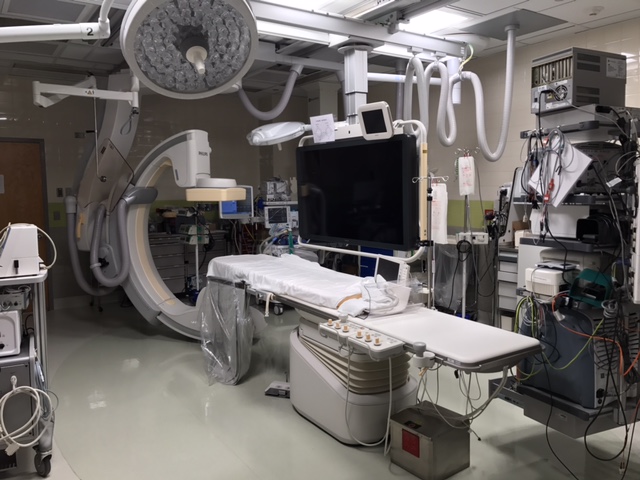

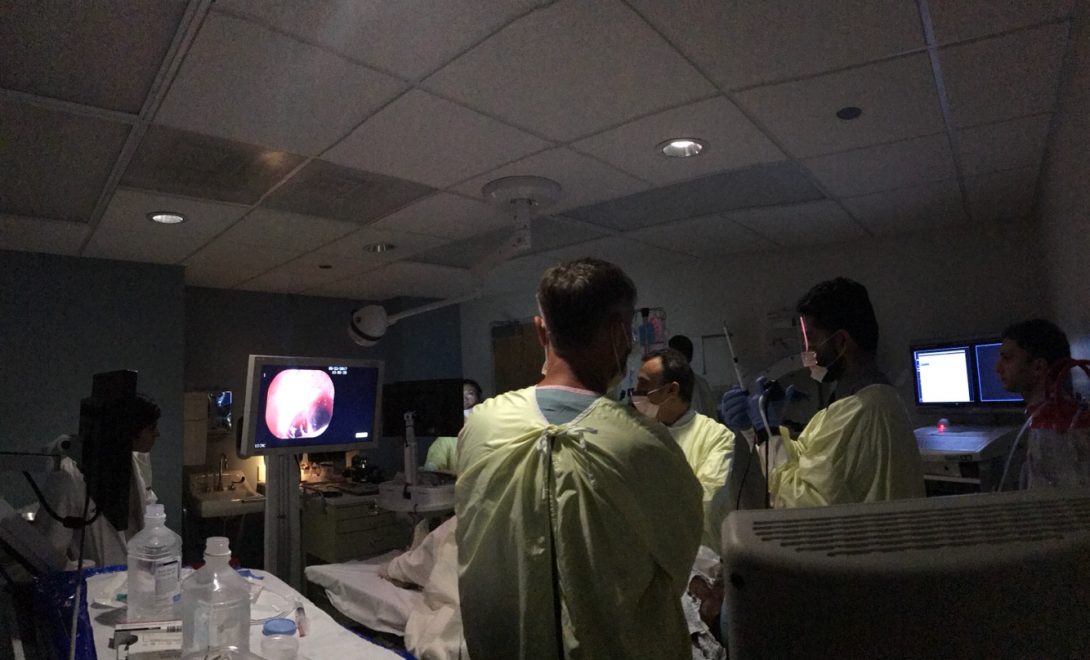

We were able to watch a procedure where an Endobronchial Ultrasound (EBUS) was used to identify lymph nodes for biopsy. This patient had previously had a biopsy done on a tumor in one of his lungs, but it only brought up dead cells. Therefore, the lymph nodes were being targeted this time to try to get a better biopsy. I noticed the ultrasound monitor was placed behind the physicians which seemed a little inconvenient (they needed to turn their heads while holding the scope).

I look forward to the next week and further developing our ideas.

Week 5 – Part 1

Najah Ahsan Blog

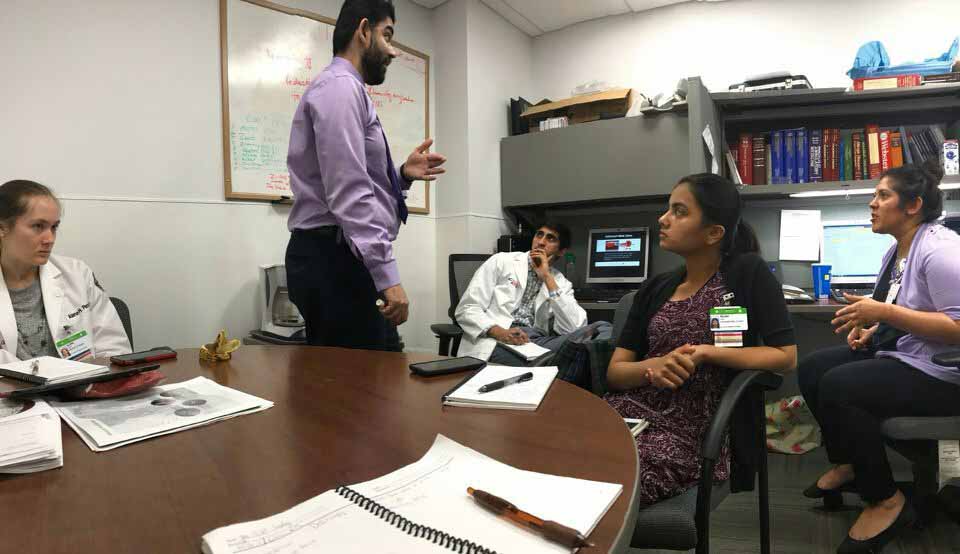

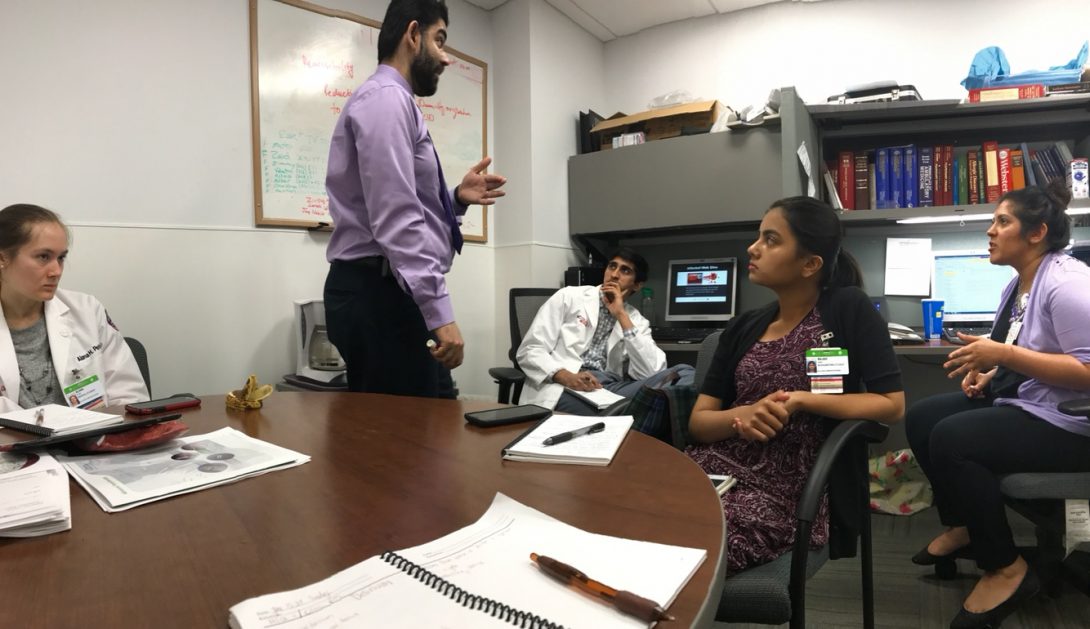

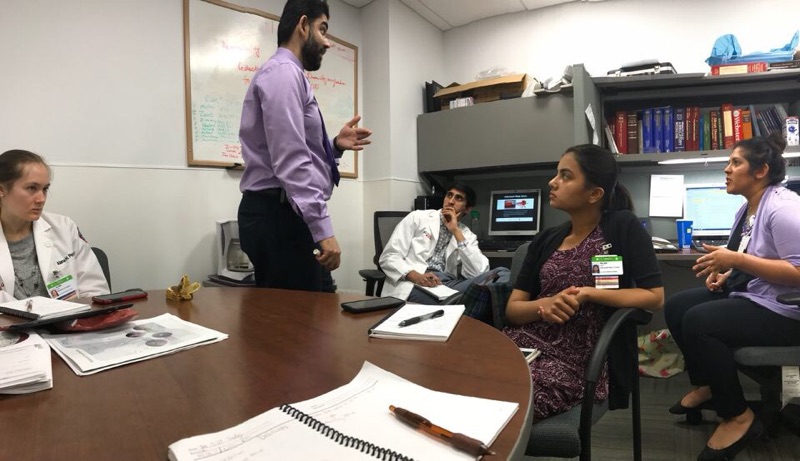

As our time in the hospital is coming to an end, this week was important to make our last observations and analysis in our rotations. The importance of communication between the Fellows, Residents, Interns and Medical Students (Fourth Year) was extremely clear. I have noticed that the “Fellows Room” is an extremely important place for them. They discuss every patient, ask questions about care plans, discuss with other departments via phone and fully discuss the patients prior to seeing them for consultations. This is also the area where the Fellows explain various concepts and field questions from the Residents, Interns, and Students. Throughout this week so far (as well as in other weeks), I have observed that the Fellows gladly answer any questions and make clarifications, and are able to do so in a more relaxed environment in the Fellow Room.

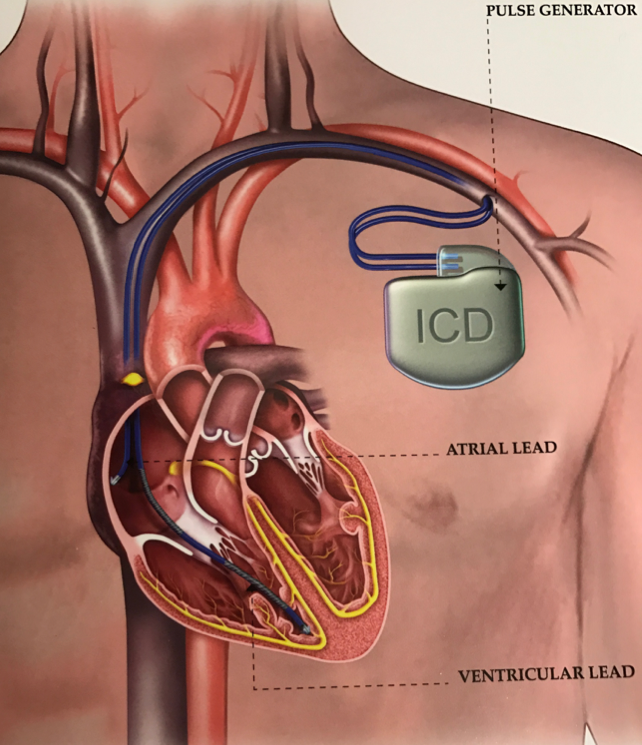

In the first clinic, the Nurse Practitioner suggested a color scheme for the inhaler stickers that we mentioned last week. She mentioned that it may be nice to have the Controller (C) stickers to be green and the Rescue (R) inhalers to be red, for it to be easy for the patients to identify the color and letter on the side of their inhaler. She also told us about a “smart pill” that has begun to be offered at Rush University Medical Center that alerts the patient when they forget to ingest a pill. It was interesting to think about the possible elimination of patients forgetting to use their inhalers or other medications if such a technology were introduced to UI Health System. One of the Fellows showed us how to tell the difference between an ICD and pacemaker on a scan as it is important to be able to determine which piece of equipment they have before treatment or further tests. During one of the patient visits, we were able to observe a different type of translator. During Week Two of this program, we saw that the physician called a translator and the patient spoke to him on the phone. This week, an “In-Demand Interpreter” system where a translator was video-called was used. This system took a few minutes to get and setup, but the video and sound quality was very good. The patients seemed very comfortable as they were able to see the translator. Overall the conversation flowed much better than the phone conversation that we witnessed a few weeks ago. The aspect of the conversation that seemed a bit confusing for both the physician and patient was the medication review. It was hard for the patient to understand the medication names. So, the Pharmacy students were given the task of reviewing the medications with the patients after the Fellow visit (this is normally the case).

Similar to previous weeks, scheduling and appointment/procedure times seemed to be difficult to predict. While reviewing consultation times, a Fellow noticed that a patient who would require a translator was only scheduled for a 20 minute slot. However, patients requiring a translator should be given a 40 minute slot. The Fellow then requested that the appointment be updated to reflect the time required. I thought it was very helpful that the appointment durations could be selected to reflect the need of the patient. Also, the procedures (such as bronchoscopies) often run later than scheduled due to factors often outside of the physician’s control (patient arrival time, preparation time, etc).

I look forward to the rest of the week.

Week 5 – Part 2

Najah Ahsan Blog

During the second half of the week, in one of the clinics the physicians and nurses were mentioning the importance for patients to understand that they need to take control of their health. During one of the appointments, a patient mentioned that he had stopped taking his medication, missed his scheduled tests, and had not seen a primary care physician for some time. This particular interaction stood out to me because it was very clear that the physicians were concerned about this patient and were trying their best to convince him to be more involved in taking care of his health (especially to avoid a previous health issue from happening again). Although the patient said that he would start going to a doctor regularly and taking medications, it was still a worry that he would not. In general, the physicians were concerned that the patients were not following instructions in their care plan.

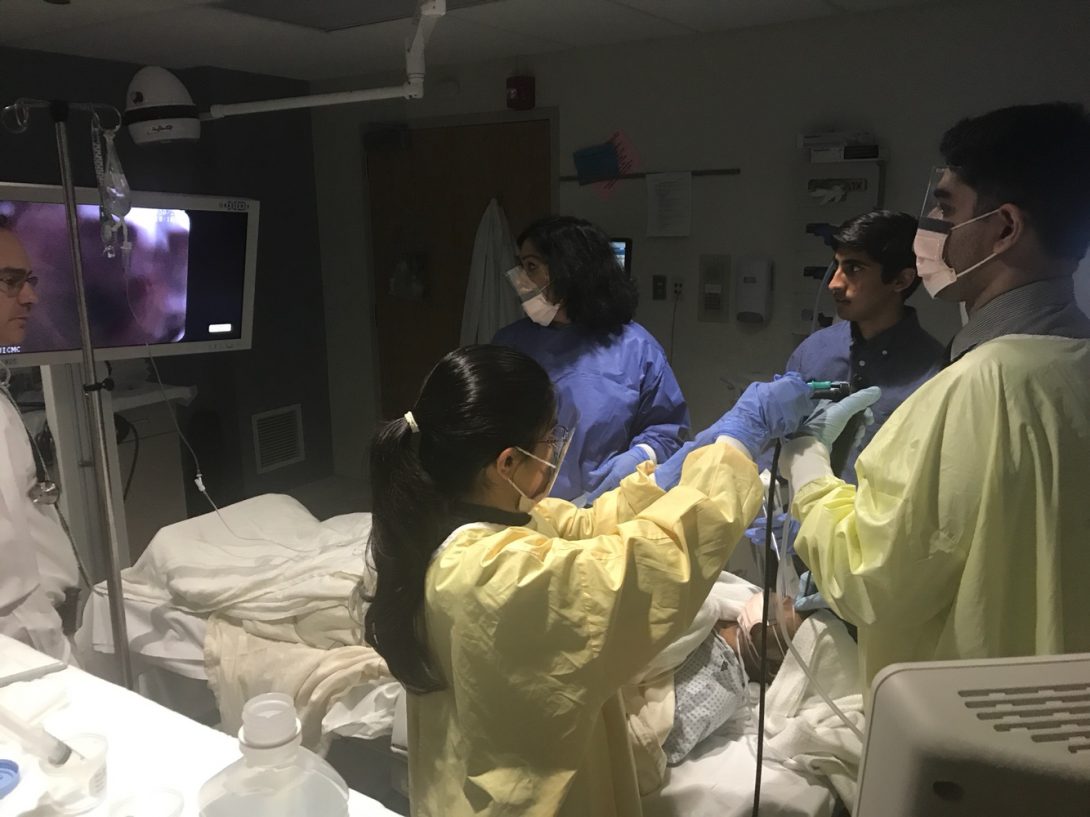

During the procedures for this week, we were given an opportunity to assist the physicians a little bit during one of the bronchoscopies (filling syringes with saline, lidocaine). It was a great opportunity to be able to be a little involved in the procedure and help the physicians with a procedure that we have seen so many times during this clinical experience. The Attending and Fellow were extremely clear with what they wanted prepared and showed me exactly what was needed prior to the procedure itself.

I look forward to preparing our final presentation and appreciate the clinical experience.

Thank you

Najah Ahsan Blog

I feel truly grateful to have been able to be a part of the Clinical Immersion Program. Everyone we encountered in our Pulmonary and Critical Care rotation was extremely welcoming and accommodating. This was such a wonderful opportunity to be able to shadow the physicians and identify potential solutions to improve the patient care in the hospital. Our final presentation to our mentor and to the rest of the members of the program was very successful and we were excited to share our observations and solutions. We look forward to continue this effort and implement our designs.

Usman Akhter

Usman Akhter Blog

Usman Akhter Blog

Wednesday 05/31 Week 1 Blog post 1

Usman Akhter Blog

Wed. 05/31 – Week 1 blog post part 1

These first few days of Clinical Immersion have been eventful. Day 1 at the Innovation Center was introductions to our new teams and discussions of what to expect. I am in Urology with Ben and Shana. We talked about design and went through examples of hospital waiting room designs. Seeing waiting rooms with activities for children and iPads was nice, but most of us agreed these things are probably too expensive for hospitals. I also think it’s a problem of hospital management time and prioritization. When building a hospital, CEOs probably find a mentor/advisor who built a successful hospital and copy their actions, including the building blueprint and interior design. Going back after the fact to renovate individual hospital sections might be low priority compared to managing insurance, for example. A 2005 studylooked at hospital design effects and frictions, and they found that, among other issues, there is insufficient compelling evidence of evidence-based hospital design benefits. Being honest about whether we’re going to make any substantial impact is probably one of the hardest parts of design thinking.

On Wednesday, our first day of actual immersion, we went to Mile Square and did not find Dr. Niederberger, but fortunately, Dr. Kocjancic and his team took us under their wing. They sit in an open room with computers against opposite walls, then a hallway further down, then another identical room of people. They don’t know each other despite sitting so close. The team is Dr. Kocjancic, 2 residents (Niki and Ryan), and about 5 MAs (medical assistants; Marisol, Gaby, Mario, and others). Doctors get 3 rooms in the clinic and variable residents per attending. They had 37 scheduled patients, and the nurse handles walk-ins as feasible. It looked like Dr. K spent over an hour signing EHR messages. This entailed repeatedly copy-pasting “I saw the patient and confirm…” and hitting sign, patient after patient. They use Powerchart EHR. One resident says the “templates suck” and are clumsy when loading lab data and so prefers EPIC. Most of the team speaks Spanish and made several phone calls to patients in Spanish. In general, I notice everyone seems pretty happy and relaxed, at least compared to my hospital visits earlier at UIH in internal medicine.

The first patient I saw had a right kidney complaint. The MA took vitals, and if patient asks, resident then comes in to get a urine sample, but the patient didn’t ask for it, so she left. The next patient had a ureteral stent for kidney stones, but the flimsy string part hanging through the urethra came out. She had to go to the ER w/ a 103 fever. Niki says this can be common because the string is so flimsy. People often forget to call for a follow-up appointment after a few months to remove the stent. Gaby says it’s not usually an issue because if the patients forget, the team will catch it and contact them.

Niki showed us an IPP, inflatable penile implant, and we noticed the pump part is very hard to press. Still, malleable implants, which stay the same size and just get bent as desired by the patient, are less frequent despite seeming easier to use in my opinion. Implants are used only after pharmaceuticals like Viagara and Cialis are tried. We learned sexual dysfunction is an ambiguous, hard to measure, quality of life issue, so a questionnaire is necessary to quantify satisfaction in some way to get insurance coverage. For whatever reason, a female questionnaire does not yet exist. We learned that psychological basis for dysfunction is uncommon, but when it exists, it’s much more prevalent in males than females.

When looking at MRIs/CTs, the team finds prostates hard to find because they need to look for darkness/shadowing. During a prostate exam I saw, Ryan couldn’t simultaneously hold the man’s penis while adjusting the flexible cystoscope, so the nurse had to help him. Another patient had pilonidal disease. Dr. K injects collagenase, which he said is very expensive, and asks the patient to physically contort the penis to make the calcification dissolve and break apart. The last patient was female and was probed to check if past surgery was successful. They usually keep the lights off to see the monitor for the cystoscope better, but this time had to turn all the lights on to get a better view of the urethra. The nurse says the tools for water in injection/release on the cystoscope and general communication with her team are great and she doesn’t run into any problems or have any complaints.

Fri 06/02 – Week 1 blog post 2

Usman Akhter Blog

On Thursday, we went to the surgical center downtown. We immediately noticed it was quite fancy and swanky. The men’s changing rooms were a bit cramped. The first surgery was a varicocelectomy, with FSH/LH levels around 16, way above the threshold of 4.

After wheeling him into the surgery room and putting him under the anesthesia, the residents shaved his hair. There weren’t enough chairs so they brought one in. They must attach to these large black pads sideways from the table so that the residents/doctor and have arm support as they’re working. I noticed before Dr. Neiderberger walked in that everyone seemed a bit worried about what might make him upset. Dr. Bakare insisted it was just kindness for others, but I suspected it had to do with him leading the surgery. They had to undo all the straps around the patient when Dr. N said the patient was about 1.5 inches too high. They unstrapped him, pushed him down the bed a little further, and re-strapped him. I wondered why they didn’t use the button to lower the bed level. Dr. Bakare was too short to properly maneuver the big head lights on top, so someone helped her. There was no space on the tables for Dr. N’s laptop and camera, so they had to clear stuff up. The anesthesiologist put a large inflatable air bag over the patient’s head. Dr. N mentioned in a past surgery the lights failed, so now they do light checks.

I noticed just set up for surgery (sterilization, placing sheets, strapping patient) takes a long time, at least an hour, though they weren’t in any rush. When scrubbing in for the surgery, you can’t touch anything in the room before getting your gloves and lab coat on, so I imagine it’s easy to accidentally contaminate and have to re-scrub again. Also, you need someone to help you with your gown so that the part you touched with your hands gets covered up as you tie up your gown. We were told to watch out for the wires on the ground sticking up a bit, because we might trip. They placed lines with a marker on the patient’s stomach where they wanted to cut. I wondered if they used permanent marker and what happens if they make a mistake. Do they have erasable markers? As the surgery started, the anesthesiologist kept her hand on the green air bag to monitor patient breathing and checked vitals once in a while. She had a lot of downtime and spent it doing a crossword. I noticed Dr. N get a little frustrated when they wouldn’t get him the right utensil during a particularly tricky, time-sensitive position. Clear communication was important. I also noticed Dr. N’s hands shaking when using the microscope – maybe because the microscope distorted his vision and orientation. The second surgery was testicular sperm extraction and went much faster. The anesthesiologist places tape over the eyes to prevent the cornea from drying out, which I thought was a pretty neat, easy solution.

On Friday, I watched a prostate surgery with a daVinci robot by Dr. Abern. The patient had to scooch from the rolled-in bed to the surgery bed, which looked a little difficult for him. The anesthesiologist had to keep a mask on him tight around the mouth with both hands, leaning back with her back to hold it tight. She got worried because she switched to intubation but forgot to switch off the ventilator because it was in the back and the switch is not easy to see. Another doctor came in and showed her what happened – she says this happens occasionally. She also mentioned that patients without teeth are sometimes harder to intubate/ventilate. I overheard the doctors talking about a recent case complication where a pubic vessel and artery got mistaken for one another because there weren’t clear landmarks on the body. I overheard Dr. Abern mention this a couple times during our surgery as well. I wonder what doctors do in tough-landmark cases. They were missing a razor in the room and had to go get one. While chatting with me, the doctors talked about how some random people will walk in to the hospital with no credentials and start interviewing people or sometimes to steal babies, which I thought was crazy.

I learned the scrubbing process is very specific. You must wash both your hands, then use your back to push the door open, otherwise your hands might be contaminated by the door. I noticed a ‘Stryker’ on-site vendor specialist for machines in the room. I wonder what he does and if he’s in the room for all surgery set-ups. Setting up took about an hour, the same as yesterday. When cutting open the stomach, the doctors/residents used metal clips to pull on the sides of the cut – it looked like it could be somewhat annoying. After another 45 minutes of surgery set up, they pulled up the da Vinci robot and spent the next 3 hours cleaning out adhesions. Apparently, this guy had so many surgeries in the past, that adhesion connections formed and they had to spend 3 hours removing them. During surgery, nurses had to replace the arms of the robot with the necessary utensil. Once they finally got to the prostate and found the cancerous part, they cut it with some tools and used this cool internal bag system that bagged the cancer and sucked itself dry around the cancer. The nurse told me they remove the bag last at the end of the surgery. I noticed the doctor having to point to a monitor next to the resident using da Vinci. He occasionally had trouble explaining the angle he wanted him to point the cutter or probe with his fingers. I wonder if you can draw on the screen like ESPN to show the person on da Vinci on their screen where to probe/cut.

Wed 06/07 – Week 2 blog post 1

Usman Akhter Blog

Wed. 06/07 – Week 2 blog post 1

Our first Monday after shadowing was presentations and group exercises. I noticed Interventional Radiology and our team both recognized difficulties identifying things on MRI/CT scan due to black/white imaging not being clear enough to identify some organs. We did group brainstorming of how observations fit into categories, and our peer practice interviews were a fun practice for when we do the same on our rotations.

On Tuesday, we were at the Urology clinic at Mile Square. There were 26 scheduled patients, way less than the 37 last week. 6 were no-shows, and 6 were seen/complete by 11 am. Nadine, a nurse, told us how important it is to start a new patient with good notes, because later all the doctors are relying on that to get a baseline understanding of the patient. Sometimes, the team forgets to make prescription orders. The lab calls later because the patient shows up, but I imagine there might be times when both sides forget. It looks like residents/fellows take patients first-come first-serve and initial their name on the list of patients so the others know who’s taking that one. Occasionally, I hear grumbling about taking a patient based on their condition or because the resident remembers them being annoying last time, but besides that, it seems like an unbiased fair system of patient assigning. I’m curious if there’s evidence of improved outcomes for randomized patient assignment, but I think it would slow down workflow because no-shows and longer-than-expected visits would screw up any pre-assigned ordering.

The first patient was angry because he came to see the doctor twice, and both times Dr. K was out, and he’s got to miss work each time. He claimed to Nadine that he never got a stent procedure and refused to talk to anyone besides Dr. K. When Dr. K showed up and spoke Spanish with him, his demeanor completely changed and he admitted more symptoms. Nadine says you can note “only wants to see Dr.” in the patient notes so we know to only schedule him when the doctor is in. I imagine this can become a problem if it’s a pattern, because Dr. K can’t see everyone everytime. Plus, it might create longer periods between visits to fit them in the schedule, which might exacerbate their conditions. Wait times listed on the EHR seem to be underestimates. A lot of patients walk up to us and complain they’ve been waiting too long. The team uses MRIs on CDs the patient gets from their primary care physician. One almost didn’t work but after about 5 minutes of tinkering on the computer, we got it loaded up.

A patient with erectile dysfunction half-jokingly gave the idea of a remote-controlled penile prosthesis. The IPP has high satisfaction, but we noticed it’s pretty hard to pump, and a remote control would probably make things easier. Dr. Abern uses myprostatecancerrisk.com, which is supposedly a validated website, to justify biopsies. Nadine takes a long time to write personalized letters for patients explaining medical excuses or embassy permission so that their family can come visit them. She says she doesn’t do templates because each case is pretty unique, but I imagine I could come up with a general enough letter that could be useful. UIC does not use phone media, only mail and pamphlets for patients, but they’re hoping to work on it in the future. I asked Dr. Abern about if he can point things out remotely on daVinci, and he said there are dual control robots but they weren’t available that day in surgery.

On Wednesday, Shana, Ben, and I split up, with me staying at Mile Square. A man had no visible blood in urine, but some amounts were detected microscopically, so the man could have prostate cancer. It could’ve been easy to overlook it because he doesn’t see the blood, but when we found out his wife is a smoker, we realized it’s important to always ask and test. One man says his appointment was at 9 but our computers said 9:45 so he was waiting for an hour. Jelena schedules surgery appointments when anesthesia is involved. She says, understandably, patients often miss appointments for non-invasive, diagnostic procedures, but show up for cancer surgeries. She often gets finance phone calls and has to email Pat, an insurance lady in Indiana. It’s a problem because Pat has no phone number, so Jelena can’t refer patients to her directly. She isn’t allowed to talk about side effects and dangers of no-shows, but she says repeatedly calling people is pretty effective at making them come. She can tell by the tone of their voice whether they care or not about the appointment. I also learned that when medicare doesn’t cover Viagra, we use a cheap generic, sildenafil, from a California compounding company. Having read a bit about the insane patent protection practices on drugs, I wonder how people make generics and how they get approval to sell them in hospitals. The saddest part of the day was when a lady with a long history battling cancer was told her urethra was clear, but she needs CT scan and cystoscopy, because a cancer might be elsewhere in her urinary tract. She reluctantly agreed only to a delayed test because she didn’t want to hear any bad news. Dr. K and Dr. Niki spent about 10 minutes trying to persuade her to do the test before she finally agreed.

Fri 06/09 Week 2- Blog Post 2

Usman Akhter Blog

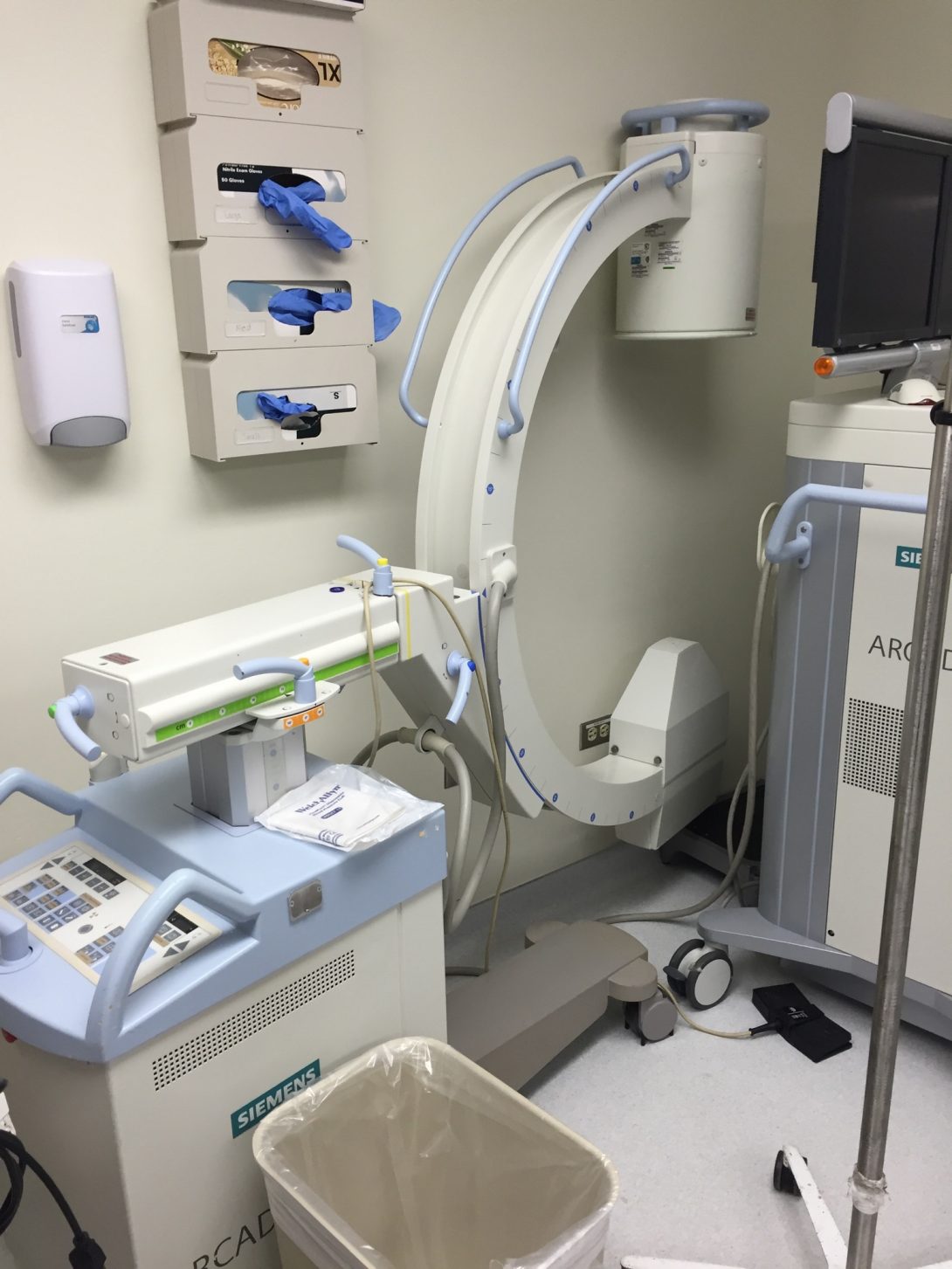

Thursday and Friday were both in the OR at UIH again. A nurse during the first surgery pointed out a few problems she runs into with the saline bag cart. Basically, there’s a large warning notecard that lies between the hooks, and when the button is clicked to raise the bags on the hooks, the bags get caught on the notecard and rip up, causing all the fluid to fall out. She said this has happened to her a few times. A radiation surgery was scheduled to obliterate kidney stones, but as they went in to find the stone, they couldn’t find it. A large X-ray machine was operated by a tech person and Dr. Abern had to regularly call out “spot,” after which the tech would hit a button to take an x-ray. They checked whether their uteroscope was properly inserted by double checking these x-rays to make sure they didn’t puncture through the ureter, which supposedly is quite common. Once inside the kidney, they couldn’t find the kidney stone, and said it might’ve gotten scooped out when they removed the stent. I was surprised that there’s no confirmation they removed the stone besides not being able to find it with the uteroscope.

96

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

X-NONE

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

On Friday we saw a prostatectomy with Dr. Abern, Tony, and Niki. Niki helped explain the actual procedure to me as they were cutting past the bladder to the prostate. When removing the prostate, a lot of care was needed to avoid the large arteries, external and internal iliac, and nerves in the area. I heard robotic surgeries might increase risk of cancer spreading, and Niki denied it. The nurse and Niki told me that the trochanter arms on the DaVinci often smack the doctors in the face as they’re working. I asked if the range of motion is limited by all the arms in the way, and Niki said it’s usually not an issue – you can just switch to another arm.

Wed 06/14 Week 3 Blog Post 1

Usman Akhter Blog

Monday at the Innovation Center we spent more time narrowing down our problems in Urology. Ben, Shana and I agreed that patient education regarding bladder removal/prostate cancer, inflatable penile prosthesis (IPP) design, ureteral stent design, and patient turnover in OR rooms were some of the most frequent and biggest issues that we want to address. We found it interesting to hear the pulmonary team talk about inhaler device use problems. By coincidence, we are interested in patient education more generally and find that inhaler technique is a common issue for patients. We wonder what sorts of solutions might work: better handout materials, take home videos, how-tos over text, or anything else.

I was sick on Tuesday but came back to the Mile Square clinic on Wednesday. I saw a patient using the IPP for the past 2 years with no success. He was upset and felt his urologist in Indiana did not properly do the procedure. The IPP didn’t wrap properly around the glans, but Dr. K said this is a common complication and not a mistake on the part of the surgeon. The patient appeared very disappointed and frustrated, claiming he got divorced, though Dr. K didn’t believe him. Nurse Nadine says it’s common to see wives leave due to erectile dysfunction. Regardless, the man didn’t seem to have much say in choosing the IPP originally. Dr. K gave him two options: fix the IPP so it wraps around the glans and improves erections or remove it and give him a malleable prosthesis instead. I could tell the man had in his mind this idea of a botched surgery (Dr. K was offering the man a 3rdopinion), and wanted someone to redo the surgery properly. Dr. K didn’t give that option and finally explained that he’d probably want the malleable. It seemed like a pretty spur of the moment decision where the patient just trusted Dr. K. I wonder if complications could have been explained earlier so the man could’ve understood his options earlier.

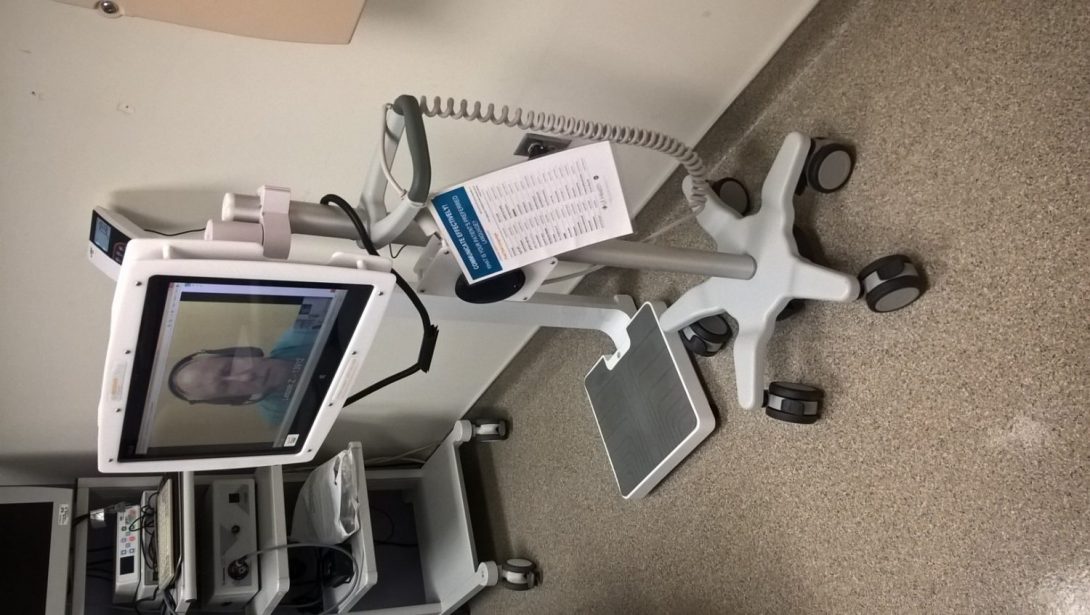

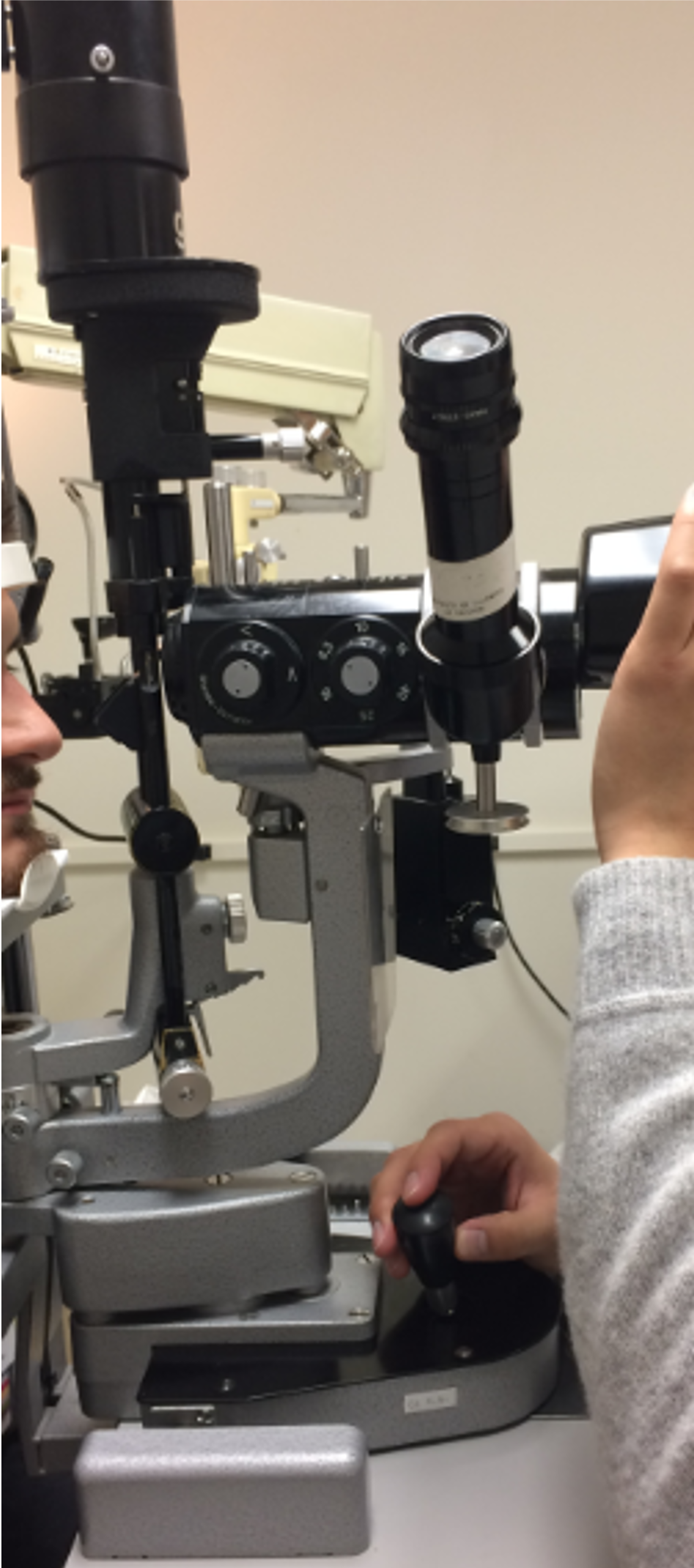

A Polish man with glioblastoma and kidney problems came in and needed a virtual translator. We had a pretty nifty monitor video system set up (pic attached) so that a translator could see and talk to him. It was a good communication exchange, but I’ve noticed that phone exchanges are much worse. The translator doesn’t know if the doctor is just making a quick comment or actually wants the comment to get translated. With multiple people in the room, it gets confusing, so the video facilitates better communication because everyone can see each other.

Fri 06/16 Week 3 Blog Post 2

Usman Akhter Blog

On Thursday we saw a urethroplasty, made out of some of the patient’s ileum. There were no issues, but I noticed sewing up the man’s incisions after surgery takes a long time. Usually, the doctors leave and let the residents do it. It took Niki around 30 minutes to finish up the suturing. I wonder if any portable sewing machine-like devices exist that could make this easier and faster. Essentially, they take a wire and snake it through both ends of the incision that they want to seal tight, just like with any sewing.

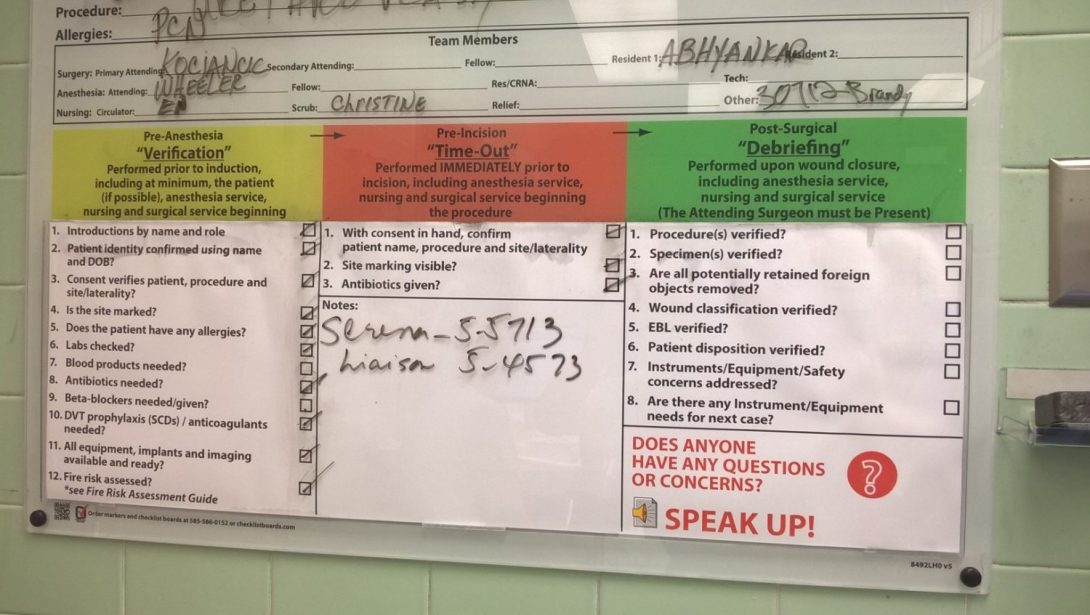

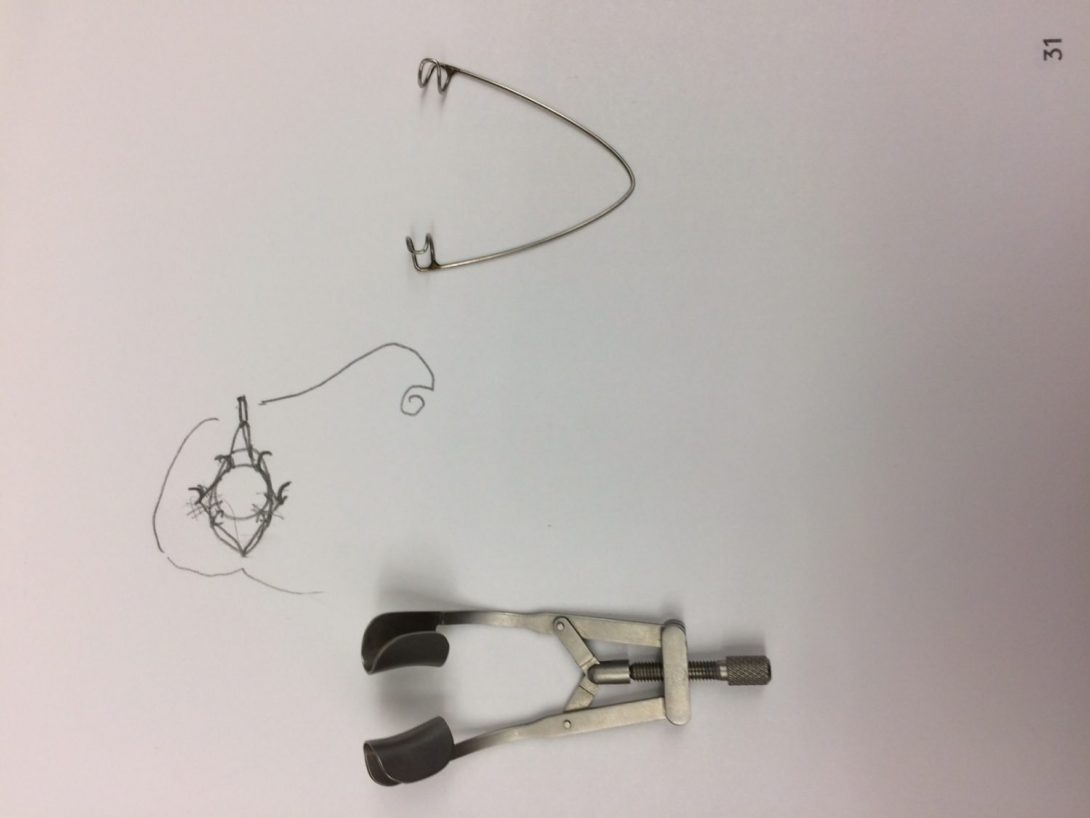

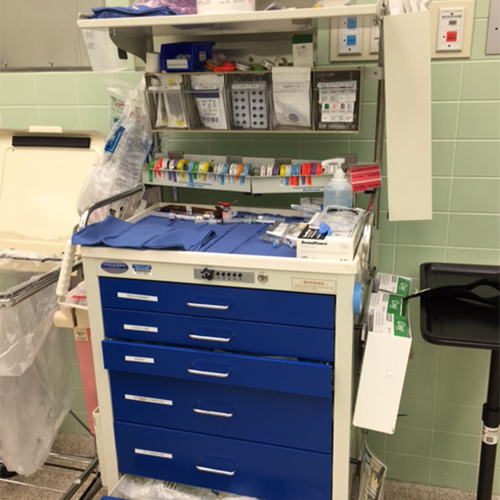

Surgery equipment checklists are a validated benefit, but I see it done inconsistently. It was done for the next Urolift surgery with the nurses checking that they had a kit and the Urolift box for surgery, but still we ran into the most time-consuming problem I’ve seen yet in the hospital. The Urolift box comes with the clipping tool to clip the prostate lobes but not the metal extender that actually enters the urethra, so UIC puts it in a separate kit. The nurses never did this surgery before and didn’t know which kit to get, so they accidentally got a similar but wrong one. The metal tool was too short, so we had to ask equipment offices to get a new one. It took no longer than 5 minutes for them to confirm they have one and are bringing it, but it took 45 minutes for them to bring it up for some reason, so we just waited around. Niki said we did the checklist at the beginning (called a ‘time-out’ – pic attached), but they don’t thoroughly check every kit and every material to make sure they have every item. They’re satisfied just knowing the box is in the room. In this way, the checklist system was flawed.

Another huge problem that day was that someone accidentally tossed a culture sample from surgery. Apparently, the nurse marked in the computer that she has it and has sent it before sending it. She then forgot to do it, and someone tossed it. Even if she did send it, there’s no step along the way to confirm it’s been properly transported and received. Without a confirmation and flagging system along each step of culture transport to the lab, it seems easy for this to happen.

96

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

X-NONE

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

On a side note, I’ve felt personally that the face masks are very annoying. I can’t see behind my head, so it’s hard to tie the straps and takes about a minute each time, and everyone’s required to wear it in the OR. During surgery, if it comes off, you need to get someone to help you tie it back on (I helped Dr. Garvey get one of his straps back on). I feel like Velcro straps would be way more convenient.

Wed 06/21 – Week 4 Blog Post 1

Usman Akhter Blog

On Monday, our team narrowed down our focus for needs assessment and settled on lab/drug ordering notification. Often, the doctors will get back to their computers and in the commotion of collaborating and addressing short-term needs, they forget to make the order for the patient who they just spoke to. The lab might eventually call when the patient shows up to ask what’s going on, but at that point, a lot of time has been wasted and the patient may be suffering as a result of their waiting. In response to this problem, we propose a voice transcription system that takes existing dictation software on phones and creates a note on the doctor’s desktop post-dictation so that they have a reminder to order and won’t forget at the end of the day.

In clinic Tues/Wed, we noticed a few more interesting cases. A Chinese man with high PSA walked in but we didn’t have clear info from his 20-page or so referral from his primary care physician. As a result, we sat there for about an hour in total just trying to figure out why he was in the office. Even with the translator, it was a huge struggle. Fortunately, his wife spoke decent English and cleared things up for us. Still, our time was probably tripled due to the language barrier. When reading through his referral packet, we searched for PSA levels due to the benign prostate hyperplasia consult, and after 3 of us searching thoroughly for about 15 minutes, we never found it. It’s a common problem that doctors are searching for 1 or 2 key facts from these packets amidst a lot of pages, and often never find it. We ended up having to call their office to get the information, which begs the question of why we have these huge referral packets in the first place.

Another issue we noticed when clearing the urine from a man’s catheter was that the urine jug can’t stand on its own. I’m not supposed to be stepping in as a helper, but the nurse and doctors often need me to do simple things like hold something in place. In this case, Nurse Nadine needed an extra hand while she used both of hers to open the tube for urine to leak out. I had to keep the jug steady. Only when the jug has urine can it stand on its own. This seems like an annoying problem that should be easily fixable.

In regards to Nadine spending lots of time writing letters, we asked her what notes she would most value if there was a template. She showed us the return to work/school form (pic attached) and showed us how the EHR lets you autosave some text in as a template. In this way, you can type up a sample letter for the patient and leave blanks where appropriate. We are considering writing up some short templates for work/school and embassy permission to speed up the typing process for Nadine.

Fri 06/23 – Week 4 Blog Post 2

Usman Akhter Blog

Thursday I went to 900 N. and saw another testicular sperm extraction surgery. Dr. Neiderberger was only briefly in the room to observe and give pointers, but it was entirely done by the residents. I took more careful time notes to keep track of time. Setting up utensils took 10 minutes, preparing patient before call-out took 20 minutes, more materials prep for another 10 minutes, and then the procedure started 40 minutes after starting set-up. I noticed an excessive number of people in a cramped area. Of the 5 people in a tight space near the man’s groin, 1 was a tech who helped pass out the utensils to the fellows, 2 were fellows doing the surgery, 1 was a resident to help with the watering syringe, and 1 nurse collected samples. I think 3 of those roles could’ve been done by 1 person (utensils, watering, sample collection). I met Dr. Shapiro for the first time, and he confirms the stereotype of Urologists being funny surgeons who make inappropriate jokes. I noticed suturing took by far the most time – 56 minutes in total. Some of this might’ve been slow due to training, but it’s remarkable how no one complains about this. Instead, I heard Dr. Bakare complain about the microscope adjustments required between users, which seemed to take at most 2 minutes per resident/fellow. I also noticed you can’t touch the large arms of the microscope because it is not sterilized – only the microscope part at the end and its handle arms are sterilized with the plastic-bag looking items around it (pic attached of Dr. Bakare almost touching the arm part).

On Friday, I saw a vaginoplasty sex change from male to female at UIH. It was remarkable to see Dr. Schechter take the skin from the man’s penis and form a vagina out of it. In the surgery room, it all looks believable, but when I stepped back to think about what we’re doing, it was incredible to take it all in. I asked Dr. K what happens when the patient feels gender dysphoria after surgery. He didn’t quite know the answer and said that’s what the surgery is meant to address. Dr. Schechter said there is often some depression post-surgery but no significant gender dysphoria. For the first time, I saw the recovery room. It is just a separate room where we roll the patient and keep them there to recover with nurses assisting. I wondered if these procedures are covered by insurance, like Medicare/Medicaid, and Niki confirmed they are. Supposedly, these surgeries are most common in Iran despite the conservative religious culture, because it is done as a corrective measure (or maybe castigation?) for homosexuals. During the surgery, the skin of the penis needs to be plucked of all hair follicles so that it’s not hairy when re-inserted as a vagina. This looked tedious, time-consuming, and error-prone.

When I asked about clinical needs, Dr. Schechter mentioned the need for better retraction tools. They use a bunch of surgical instruments/scissor-looking clip devices to hold together sutures and keep the surgical area open without tying up people’s hands. Dr. C from Urology at UIC supposedly invented a suturing sewing machine device and won a prize for it, but Niki doesn’t know where it has gone since then. I hope I can speak to him about his progress on it. When speaking to some nurses, I also noticed them complaining about inefficient employee assignment. Nurses on flex were not on call during an overtime period, but the full-time nurse was being held overtime instead (they noted she probably gets paid higher and doesn’t want to be there overtime, so it’s a waste keeping her on call instead of the flex nurse).

96

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

X-NONE

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

Week 5 Blog Post 1

Usman Akhter Blog

At Mile Square, I took note of physician time per patient for Dr. C. He got through 10 patients between around 8:00 through 11:45. That’s 22.5 minutes / patient on average. 5 were no-shows, so 1 doctor can get through 15 ‘scheduled’ patients in 4 hours, or almost 4 scheduled patients/hour. I think that’s on the faster end, usually doctors can’t get through that many patients. In total that morning, the doctors got through 17 patients in the 4 hours of the morning. I didn’t track how many doctors/nurses, so this isn’t very meaningful.

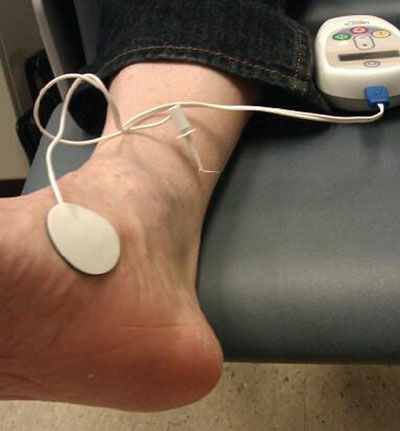

One woman had a neural issue with her bladder. No options exist besides using a catheter forever if neuromodulation doesn’t work (pic of device). She didn’t seem to fully understand that a ‘procedure’ still counts as a surgery, as they insert a pacemaker-like device to control bladder contraction. In general, I get the feeling a lot of patient knowledge comes from Googling stuff at home.

96

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

X-NONE

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

When we presented our voiding idea to Dr. K, he mentioned how volume is important in addition to flow. We’ll continue brainstorming our ideas.

Week 5 Blog Post 2

Usman Akhter Blog

96

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

X-NONE

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

We spent remaining time researching our ideas and would prefer to keep that research private. (pic of our brainstorming attached)

96

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

X-NONE

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

Week 6 Blogs

Usman Akhter Blog

Unfortunately, I spent less time in clinic this week and didn’t take thorough notes, so I have no updates to add this week. We spent time researching our ideas on our own as a team and following up in clinic to get feedback from Dr. K and the rest of the Urology team.

Bekah Allen

Rising senior in the bioengineering program with a concentration in neural engineering. My rotation for this program will be in cardiology. With a basic understanding of the heart, I am very excited to see what I can learn from medical experts in this area, and how I can apply my knowledge of engineering principles to this project!

Bekah Allen Blog

Bekah Allen Blog

Immersion

Bekah Allen Blog

This week has started with a lot of unknowns but an overwhelming amount of excitement for everything that this six-week adventure in the cardiology unit would entail! Our very first day of the program started how it will every Monday (except it was Tuesday due to Memorial Day); an entire program meeting to first give a run down of the program, and then guide us through different concepts in these initial stages of design. Although we will be in our respective units mainly observing, this, in fact, is the first stage of the design process, and a very important one at that. This is why it’s called a needs assessment. Designing devices that no one needs or would be able to use would just be a waste of time and money. We discussed the importance of creating devices that are desirable, viable, feasible, as well as having a human-centered design. Human-centered design is a term that is used often but is one of the reasons I am so excited for this program. Understanding how products I may potentially develop will affect and integrate into the workflow for the end users such as doctors, nurses, technicians, clinicians, etc, will give insight I might not have had otherwise.

For our first week in the hospital setting, the focus was to observe and get a better understanding of the cardiology unit, not to find opportunities quite yet. Our first day in the hospital on Wednesday started with a meeting with the chief of cardiology, Dr. Darbar. He explained his background, as well as his take on the ever-changing trend in technology, which was an interesting perspective to hear. He spoke of how the technology for mainly imaging has advanced greatly compared to when he had done his training. But he could also tell where the current trend in technology advancements are heading for electrophysiology (EP). The next part of our day was spent with Dr. Gans in the echo lab.He seemed to appreciate the technology that was used currently for his job and seemed content with his current workflow. Which was obvious after spending a couple of hours with him; I’m not sure an autonomous robot would even be able to examine 75 different images of the heart, to accurately update a patient’s medical record faster than Dr. Gans was able to complete one (when we weren’t asking ten questions per minute). The last part of the day was spent in the cardiology fellows room, listening to the senior resident present multiple patients’ cases to Dr. Stamos, Director of General Cardiology Fellowship. We actually then got to go on their rounds with them to the various patients. This wrapped up the day for us, with a lot of things to take in and observations to review.

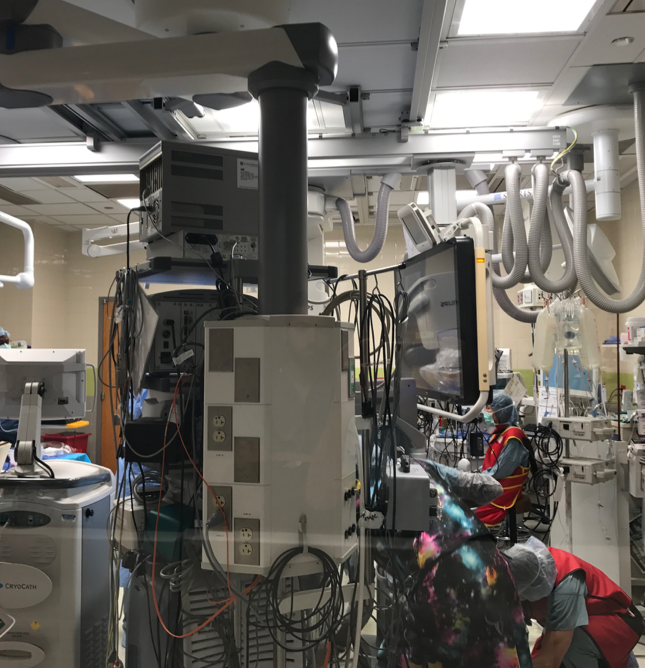

Day two came on Thursday, which was spent with Dr. Ardati, an interventional cardiologist. It was interesting to see the comparison of the two days, the first that appeared to have less obvious needs for innovation versus the second where there were immediate issues that were addressed for improvement. While this week was intended for mainly observation, it was hard to not immediately start brainstorming ideas.

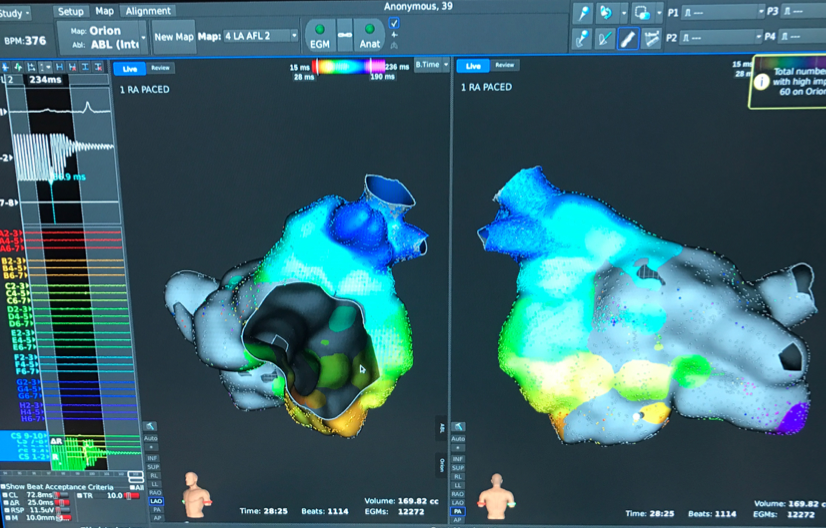

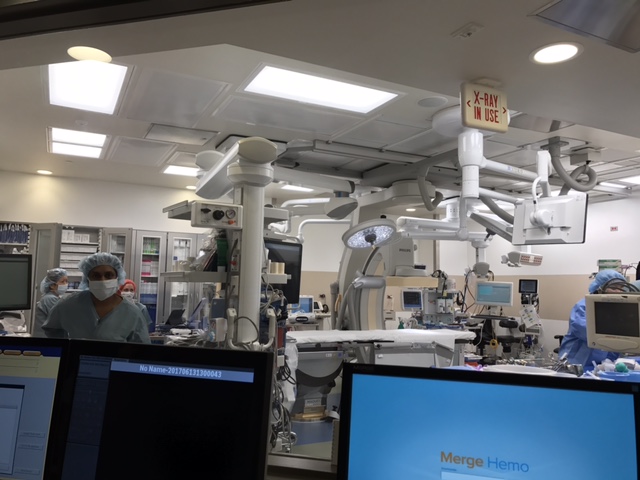

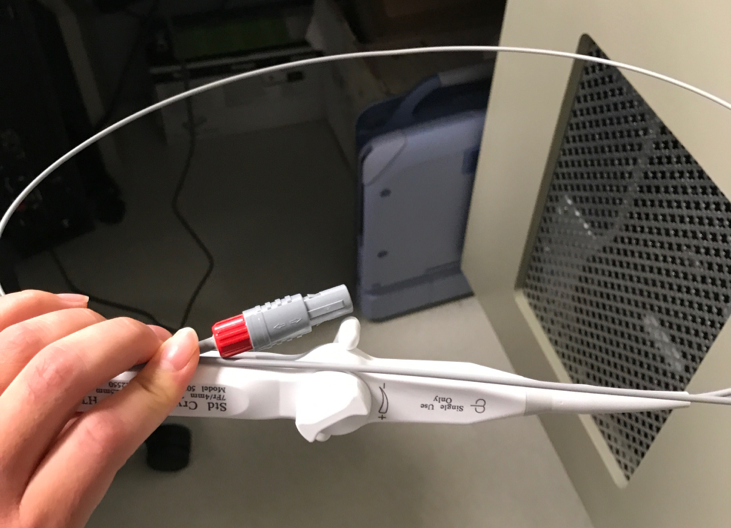

Before we knew it, it was already Friday and the last day of our first week in the program. Because our mentor, Dr. Wissner, had been out of town teaching medicine in Iran, this was the first day we were able to meet him. Immediately talking to him, it was clear he was passionate about this field, and thus I am very excited to have him as a mentor. He mentioned how there was a large amount of bioengineering possibility in ablation and catheters; whether it’s non-invasive mapping systems, catheter design, navigation, etc. One quote that Dr. Wissner said that stuck out to me was “Ablation is a cure”. This was interesting to me because this isn’t always something that is possible or true in medicine. Dr. Wissner talked of one patient showcased on the hospital’s wall, who benefitted from both the cure of ablation and the engineering of non-invasive mapping systems. She was a patient with a heart condition that had worsened with pregnancy, and could not receive the standard procedure with fluoroscopy for the safety of the baby. Dr. Wissner was able to utilize a 3D mapping system to safely ablate the areas of the patient’s heart and cure the disease! We then got to meet with Dr. Shroff, an interventional cardiologist, who was just finishing up a stress test for a patient needing clearance for a kidney transplant. He also mentioned that interventional cardiology is growing because of a true collaboration between clinicians, engineers, and pharmacists. After just a few days in the cardiology unit, I could already tell how true this was. I cannot wait to learn more while in the cardiology rotation for the next six weeks and hopefully can be a part of the equation that will continue the innovation that is helping patients like the one Dr. Wissner treated!

Scrub Up

Bekah Allen Blog