Students: Part 2

Celine Macaraniag

Celine Macaraniag

Hi, I’m Celine! I am a senior bioengineering student with a concentration in cell and tissue engineering. I am excited to be joining the Pulmonary Critical Care division this summer to learn more about current existing clinical problems in the hospital. I hope to enhance my knowledge about user-centered design for medical devices and patient treatments through this program and apply them to future projects and research.

Celine Macaraniag Blog

Celine Macaraniag Blog

Week 1: A little bit of everything

Celine Macaraniag Blog

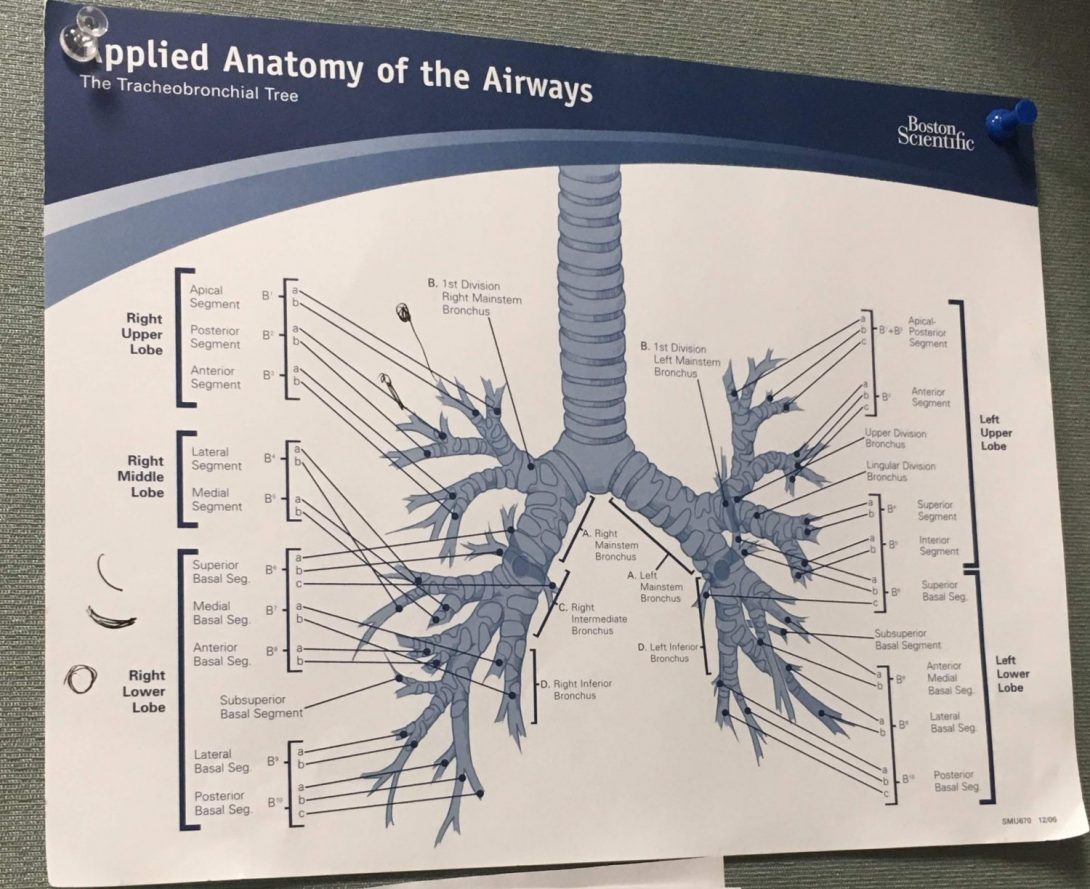

During our first week of clinicals, my partner and I got to see a little bit of each of the parts of the Pulmonary, Critical Care, Sleep, and Allergy Division. The division consisted of the intensive care unit, the pulmonary clinic, the pulmonary function test lab, and the sleep center. We went to all these different areas and met several attending physicians, residents, fellows, and medical technologists. On the first day of clinics, we got to visit the intensive care unit or the ICU, where we followed a team of doctors to each patient’s room and listened in on their care plan for the day. During clinics, we shadowed Dr. Jeffrey Jacobson and Dr. Dustin Fraidenburg and got to observe their workflows and interactions with different patients. We also got to witness a bronchoscopy procedure, specifically, a transbronchial biopsy and a bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). We met Dr. Muhammad Najjar in his sleep clinic, where we got to learn about sleep studies in patients who have may have sleep disorders. Finally, we got to visit the pulmonary function test lab where pulmonary function tests or PFTs are performed.

While we saw many important areas in the division, I will focus on the pulmonary function lab for this blog. In the pulmonary function lab, the PFTs are conducted by a technologist to measure a patient’s lung volume, capacity, and other flow rates. Ryan and I were lucky enough to get to try this test out ourselves. We agreed that the test went well for the both of us. The equipment used, called body plethysmograph, was comfortable for both of us, since the equipment was adjustable to accommodate the user. In the end, we even got to review our measurements and determine that the health of our lungs!

Another test they do is what’s called a six-minute walk test. This test is used to measure a patient’s walking distance in 6 minutes. This helps the pulmonologist to determine if the patient needs some oxygen help from an oxygen tank. During our observation, Ryan noticed that there were several obstacles in the hallway where the test was taking place. Several objects were placed by the sides of hallway such as a hospital bed, some cleaning supplies, a wheelchair, etc. This was the perfect opportunity for us to apply the AEIOU framework:

- A- Activity: The walking test. Technologist walks patient back and forth the hallway for 6 minutes.

- E- Environment: The hospital hallway. Other people in the hallways interrupted the test (other patients being wheeled in and out of rooms).

- I- Interaction: Technologist walks with patient during the test while wheeling around a monitor and an oxygen tank.

- O- Objects: Monitor, oxygen tank, wheeling device, clipboard, stopwatch. Other objects not used for test: bed, chair, cleaning supplies.

- U- User: Pulmonary technologist and patient.

This test fits perfectly in the AEIOU framework and it helped us identify problems in the activity; for example, the objects in the hallway and other people walking in and out of rooms interrupted the test several times which made the test less accurate. I also noticed that the tech had to bend lower to reach his clipboard to write while also walking; this can potentially cause some handwritten mistakes. The test can be improved by either the following: 1) switching to a different location where no objects/people will interrupt or 2) find a way to get rid of the extra objects that act as obstacles and alert people walking in the hallway that a test is being done. In this way, people will know to avoid blocking the way where the patient is walking. The main goal is to make the test as accurate as possible so that proper assessment can be done.

Week 2: PFT Lab

Celine Macaraniag Blog

We had yet another insightful week at the Pulmonary Critical Care unit! Ryan and I got to see a lot more of the pulmonary clinics, the ICU, and the sleep clinic. For this blog, I will focus again on the Pulmonary Function Test (PFT) lab; it seems that my partner and I have found another element to the PFT lab that may need some more improvement.

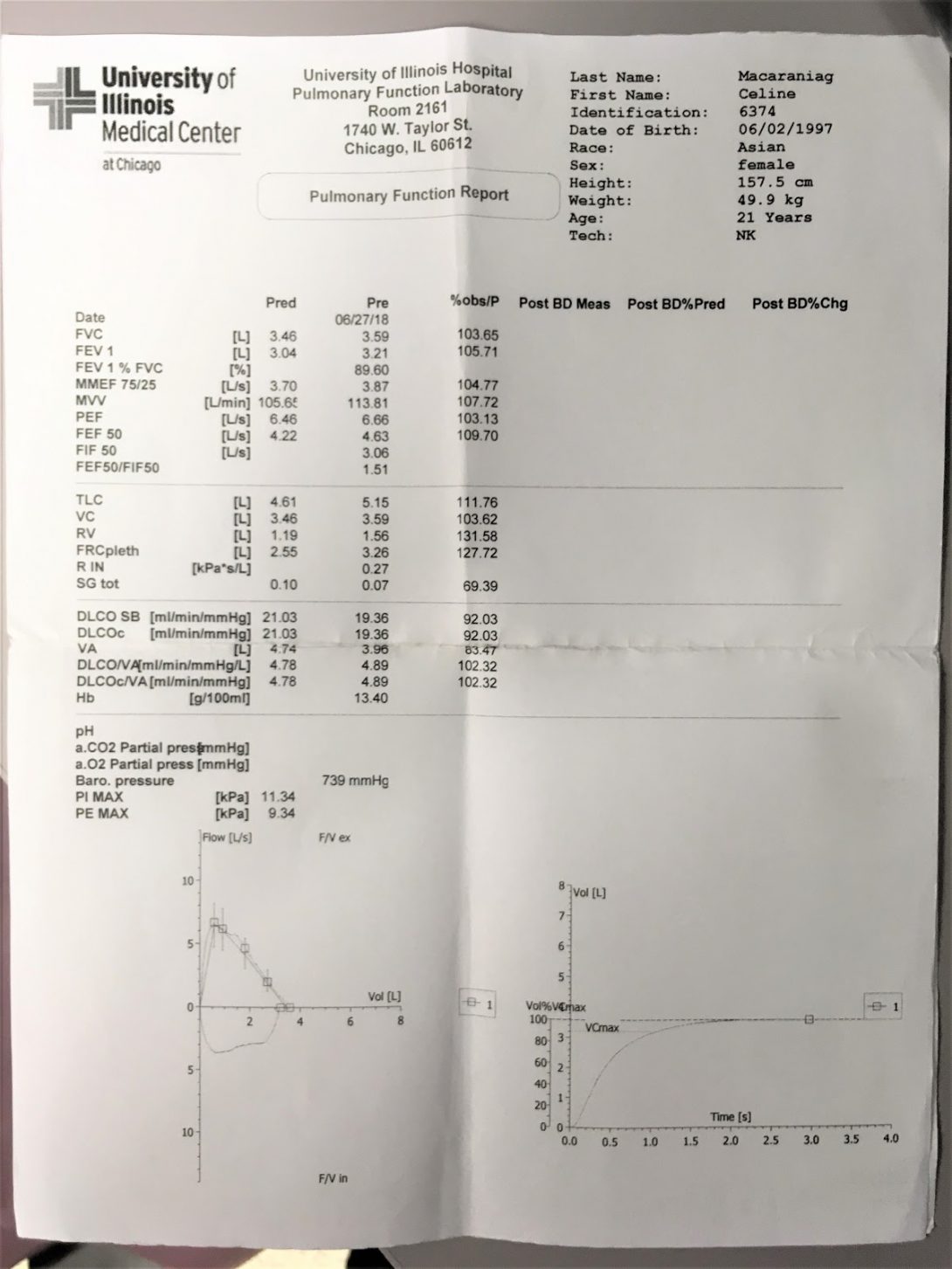

After PFT sessions are completed, patients are usually given a sheet of results listing multiple PFT values for the patient’s physician to read. However, the patients do not necessarily understand these results. I certainly was unable to interpret my own results. I did not know what most of the values on the page meant; there were acronyms next to these numbers as well, and I was only able to recognize those that I had previously learned from an old physiology class. Ryan was able to explain some of them to me, but, he also thought that it would be much better if there was a way to communicate the PFT numbers to people like me who aren’t familiar with them. This led us to try to investigate the PFT lab further to better understand the process.

We came up with a storyboard that details the step-by-step process of a complete PFT. We also identified potential pain points that may complicate each step.

PP = Pain Points

- Patient visits PFT lab.

- PP:Many patients usually cancel their visit; this may be due to weather conditions (i.e. too hot or too cold outside).

- Tech generates PFT report after tests are done. Tech gives hard copy to the patient.

- PP:Tech would have to scan the report and it would take about 4 days for the report to get into the system.

- Patients try to decipher their PFT report.

- PP:Patients may not understand what their report means.ÂÂ

- PP:Independent research may lead to more confusion.

- Patients give their hard copy of the PFT report to their physician.

- PP:Patients may lose their hard copy of the report. Or they may forget to bring the report to their visit to the clinic.

- Physician reads PFT report.

- PP:The physician only sees most recent PFT, but may want to see progress of patient and would need to find PFT reports from previous visits.

- Physician educates patient about their lung health.

- PP:Patient may still not fully understand. Physician may educate patients about essential details, but miss out on an opportunity to build patient understanding of their condition.

Identifying these potential pain points was beneficial in trying to learn more about how PFTs are conducted. We wanted to fully understand the process to try to come up with ways to better the system so that patients can have more insight to their own lung functions and therefore have a more active role in their health care.

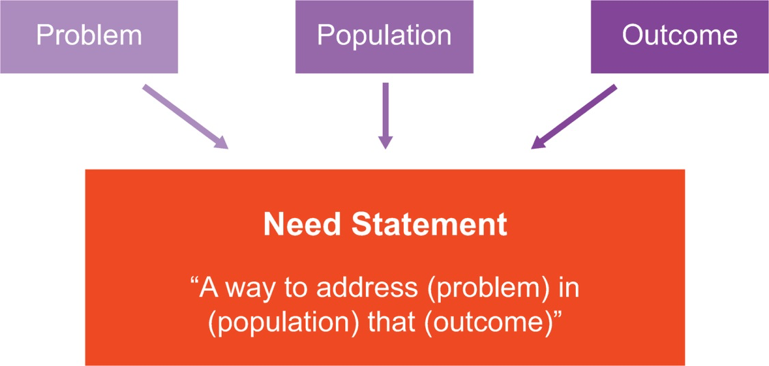

Week 3: Needs Statements

Celine Macaraniag Blog

This week, Ryan and I went back to all the parts of the Pulmonary Critical Care unit to find more potential areas of improvement. We also started coming up with different iterations of needs statements for our initial idea on improving the layout of pulmonary function test (PFT) reports.

To recap, the PFT reports, generated by the pulmonary technologist, consists of several values that determine a patient’s lung function. This document can be very confusing to the patient. Â An image of the actual PFT report can be seen below.

Celine Macaraniag Blog

Image

Celine Macaraniag Blog

This week, we tried to focus on finalizing our needs statement and developing some high-level specifications for our project regarding the pulmonary function test reports.

After talking to our mentor, Dr. Dudek, we found out that UIH is beginning to integrate a new electronic medical record system. This means that the current the electronic system for medical records will soon be replaced. Because of this, making changes to the current system will be rendered useless. However, we would still like to create something that improves patient education about their lung condition.

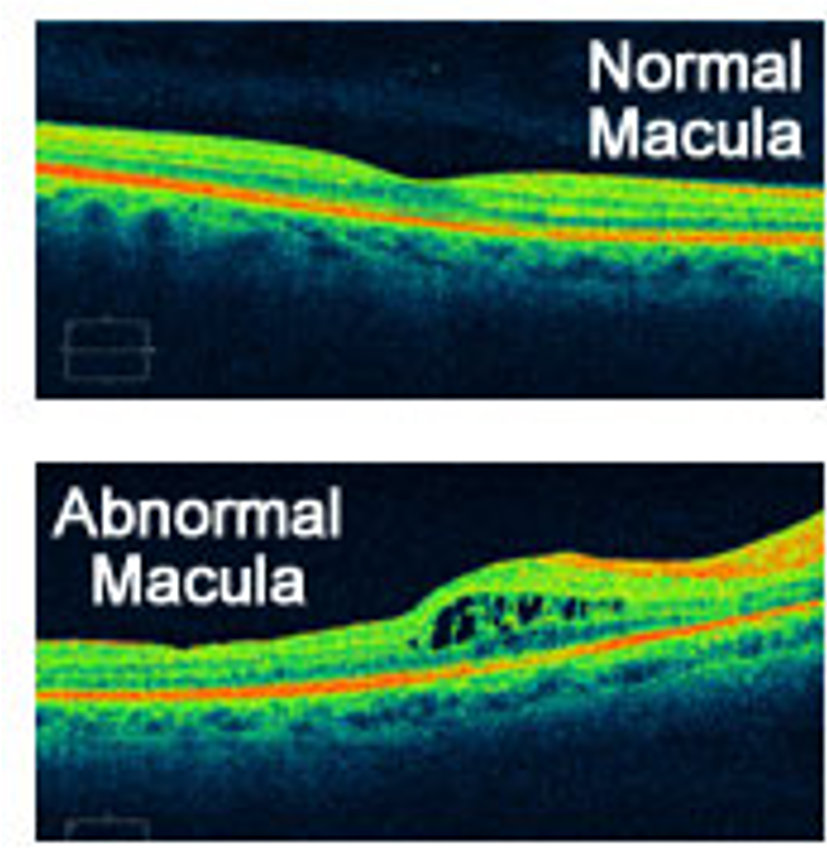

We brainstormed on different concepts for improving PFT reporting and came up with these specifications: intuitive, appealing, easy to implement, and effective. To better communicate patient PFT reports, we thought that a more intuitive and appealing method should be used so that patients will show more interest in the otherwise very intimidating set of numbers. The PFT values aren’t actually difficult to grasp; for example total lung capacity is the maximum amount of air contained in the lungs after taking a deep breath; and this number can determine lung restriction. Simple definitions like these are great for all patients to have a better idea of what their PFT reports mean. A good example on how this can be done is shown in the graphic below.

Week 5: Last Days

Celine Macaraniag Blog

Image

John Marsiglio

John earned both his B.S. and M.S in Chemical Engineering from Northwestern University. His interest for innovation was first sparked by an internship at a speciality chemicals company in the Joliet, IL. Before coming to medical school, John worked in drug product development at GlaxoSmithKline’s global vaccines R&D center in Rockville, MD, while spending his weekends backpacking in the Mid-Atlantic. In the IMED program he hopes to leverage his knowledge of transport phenomenon, materials science, and process design to produce innovations that could be clinically relevant.

John Marsiglio Blog

John Marsiglio Blog

ABCs and AEIOUs of Anesthesiology

John Marsiglio Blog

My first day in the OR began bright and early at 6:30 on a Tuesday. I met with Austin Buen-Gharib, a senior in bioengineering to begin our clinical day in the anesthesiology department. From an outsider’s perspective the OR is a buzz of activity, everyone moving quickly to complete their tasks, kind of like a bee hive. We met with Dr. Nishioka, medical director of the OR and anesthesiology attending, and he wasted no time bringing us to check in on a resident doing the anesthesiology for a coronary artery bypass graft. From a lay person’s perspective anesthesiology is often an afterthought. Patients are far more focused on the surgeon than the anesthesiology team. Seeing the anesthesiologists view of the surgery it quickly became apparent to me that the anesthesiologist does a lot more than the patient might expect. Throughout general anesthesia the anesthesiologist must pay careful attention to the patient, and anticipate all possible risks to the patient’s vitals that surgery may entail. The anesthesiologist must also interpret screens of readings, and be able to make adjustments to various instruments to keep all vitals within range.

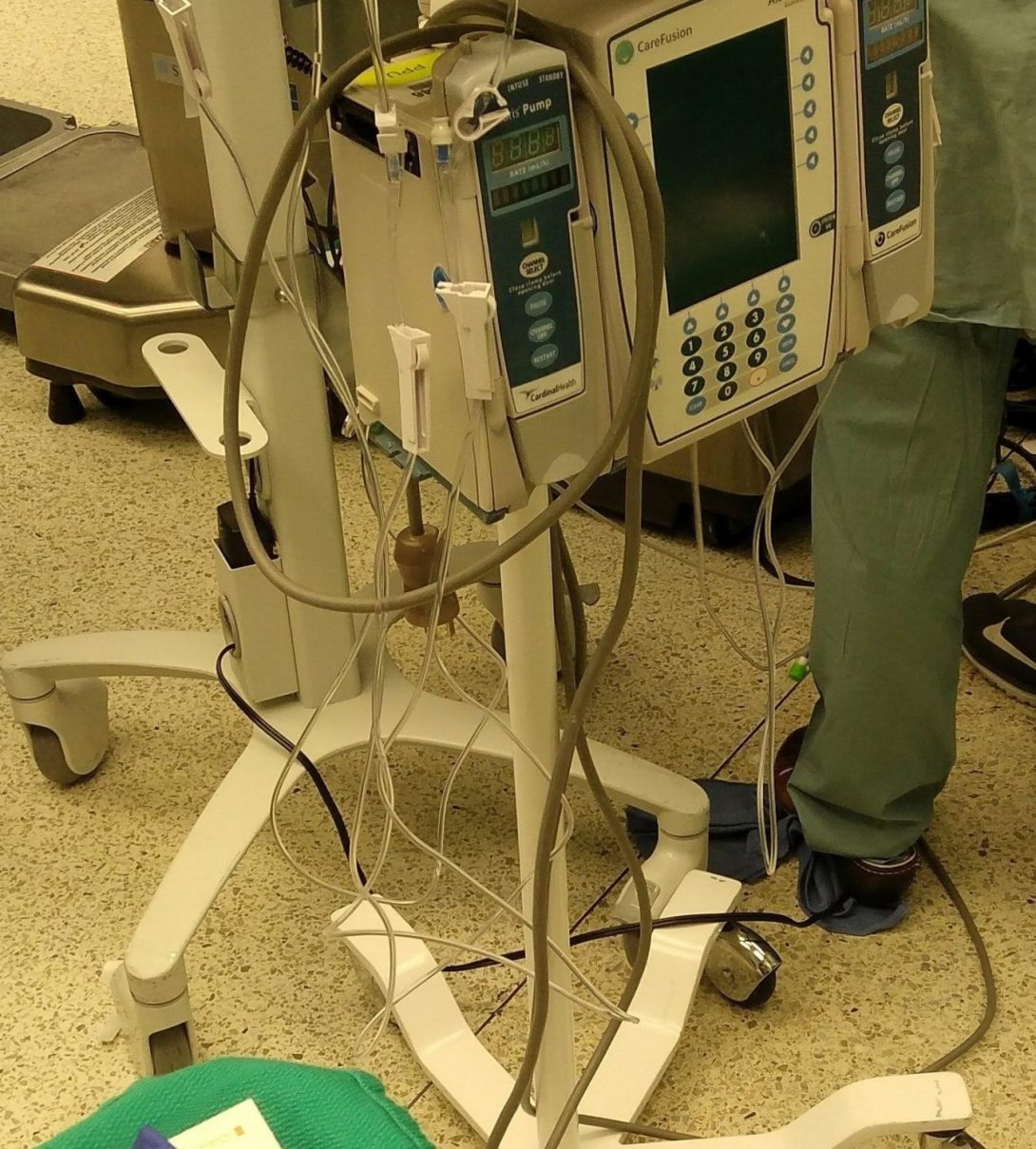

Austin and I are lucky to have Dr. Nishioka as a mentor. He’s happy to spend the day with us, patiently answering our questions and guiding us through the different OR’s. After a few days Austin and I began to generate some ideas that could fit into the AEIOUs of our design framework. One of the first things we noticed about the OR was the mess of cords everywhere. There were many times when OR staff struggled to roll equipment over the mess of cords. We thought surely there could be a better way. Another idea we liked talking about was how the different anesthesiology attendings communicated. Dr. Nishioka carries at least 2 phones at any one time, and if he’s the case board runner he’ll carry 3. There have been a few times where he’s had to talk on two phones at once. As a first pass at applying the AEIOU framework to the latter situation:

- Activities – Communication between different attendings on OR statuses

- Environment – OR/recovery room/pre-op

- Interactions – Physician-Physician Interaction

- Objects – phones, texts and visual displays

- Users – Attendings, residents and anesthesiology technicians

For our next steps we will have to consider other inefficiencies in the OR, along with their impact on patient experiences and physician time wasted. We will also have to consider what sort of issues are the cause of the problems, and what other factors are at play. We realize that some issues we see may be due to structural problems with the hospital that we might not be able to change, while others we might have a good chance at taking a stab at a solution. We look forward to the next few weeks of refining our ideas and moving forward to address one of many clinical needs.

Problems abound!

John Marsiglio Blog

I think after two weeks in the OR with anesthesiology what astonishes me the most is how many inefficiencies could be streamlined. I think the average person has the impression that an OR is this kind of sleek assembly line- staff moving from patient to patient in a calm, cool way, just like on the TV shows. In reality, like any job environment, there are any number of things that impede smooth workflow, and of course act as stressors on the staff.

From our perspective these inefficiencies represent opportunities for innovation. Offhand Austin and I have begun noting all of the potential problems our project could tackle. One piece of wisdom Dr. Nishioka gave us was to also think about the impact of our project, while something that benefited UIH would be nice, something that could benefit all hospitals would be even better. A good example of this is the cords in the OR. While many of UIH’s ORs have a jumble of cords on the floor, one OR we visited had a disposable strip (photo above) that immobilized the cord. While cords in the OR is still a problem, it’s clearly only a problem in some of UIH’s ORs, so it would be a very narrow problem. He also pointed out that another common problem innovators run into is failure for the intended populations to adapt, citing a recent program UIH had implemented that had low compliance. Our next steps will have to involve taking all the opportunities we see and narrowing down on them based on their clinical impact, staff interest in using that innovation, and of course how feasible it’d be for us to complete in the remaining few weeks of clinical immersion.

In the next week we hope to set aside some time to get our ideas out, start considering how they fall based on impact, interest, and feasibility, and storyboard a few to further ratchet down on the meat of the issue.

Needs and Problems

John Marsiglio Blog

This week our topic on needs statements really got Austin and I thinking. We have seen so much in the UIH OR’s so far, and frankly there are just so many needs. This week one case that really stuck with me was following Dr. Nishioka while he was board runner for the day’s anesthesia cases. The function of board runner is to basically track all the surgeries going on in all OR’s, trying to give residents and attendings breaks when needs, and working to balance add-ons and other changes to the schedule. While it doesn’t sound terribly overwhelming, it does boil down to Dr. Nishioka running around the different ORs from 6am-6pm. This job is so stressful for a few reasons. There’s the problem of the add-on, where a case comes in that does need to be done that day, like an appendectomy, and there’s the problem of an emergency, where a room needs to be opened right now for a patient in need. The latter was the case when a woman came in with a ruptured uterine cyst. These emergency cases obviously can’t be helped, and there isn’t much to do for the add-ons either to make it easier on the anesthesiology team. However, while an short term observer may think that these two things are the source of most of the stress for the board runner, as a long term observer I’d disagree. It seems to me that the most stressful part is that cases aren’t starting on time, which leads to delays snowballing, and trouble staffing. There are many reasons why a case doesn’t start on time. Some aren’t things we can control, like a patient being late, or another case lasting too long, or even a more difficult than anticipated procedure. However, reasons for delays are most often something we can fix, like patients not being brought to the room on time, surgery delays, or anesthesia delays. Dr. Nishioka’s project, the iShuddle, seeks to help address these problems by having the charge nurse announce at the end of each case when staff need to be back in the room, and before beginning the next case announce if there is a delay and what is the reason.

The only problem is that we’ve rarely seen this system used. Yes everyone has been trained and they are supposed to use it. We’ve conducted some interviews and staff seem to not use it for many reasons, it being another task to manage, being too busy, or thinking that it might become a blame game. Austin and I have heard a lot about the issues with the iShuddle and the issues it seeks to address. We spent a lot of this week drafting needs statements, and found it more difficult than expected. We’ve also been wondering what exactly is the problem with the iShuddle? Is it not a good system, is it too cumbersome, or is there something about the culture or maybe incentives that could need to change for it to be effective? We hope to further explore these questions next week.

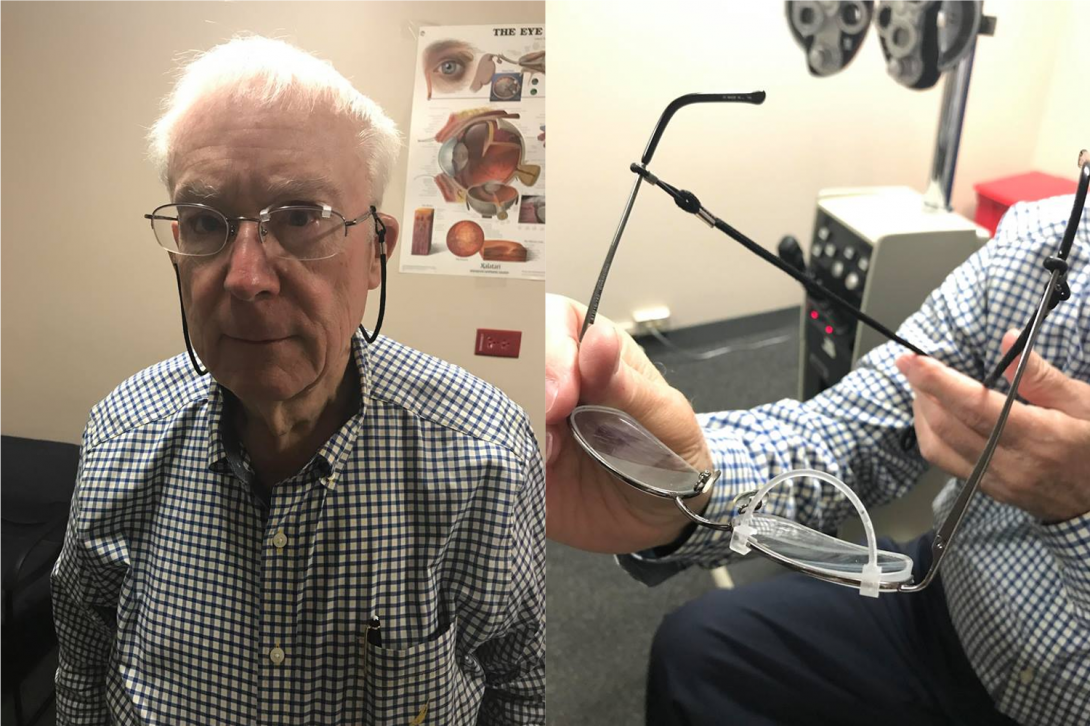

Spectacles and Specifications

John Marsiglio Blog

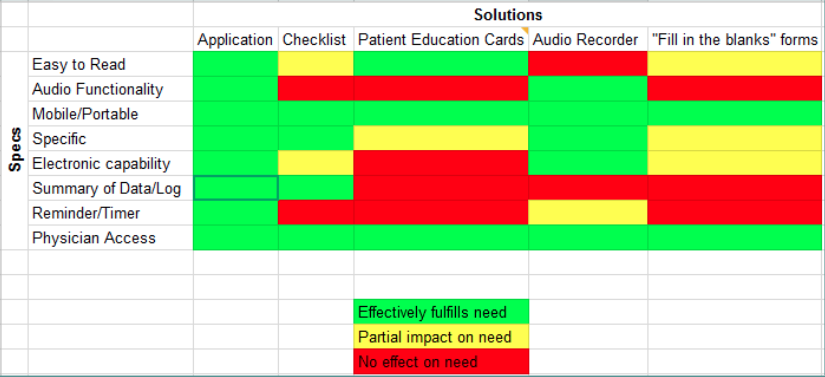

This week in the OR Austin and I spent considerable time discussing what specifications will help improve turn over time. I think we’re beginning to appreciate just how difficult a problem this is to tackle. It seems like with each person we talk to about turn over times we get a new reason for why they are consistently behind. From these different conversations we tried to hone in on the broader problems, and from there took a stab at thinking about what kind of improvements would eliminate that problem. Moving forward we generated a list of specifications.

From this list of specifications we decided that some were much more important than others, especially considering the difficulty there has been adopting the iShuddle system. Austin and I each assigned weights to the specifications, and we can broadly place them into three categories: very important, moderately important and not very important (the “would be nice” category”). We identified predicted impact on turn over time and willingness to adopt both as very important. This is because turn over time is our goal, and willingness to adopt is a huge struggle for the current system. This brings to mind a past lecture where we went over that something cannot be considered an innovation unless it is adopted and used. Secondly we identified ease of implementation and ease of use as moderately important specifications. Both are important as they would be big factors the hospital administration would consider when asked if they’d adopt a new system. Finally we thought a few other specifications would be good to include, but that they weren’t super important. These were cost, time to implement, and finally safety. While all variations we thought of were very safe, we felt that safety should always be a consideration in healthcare.

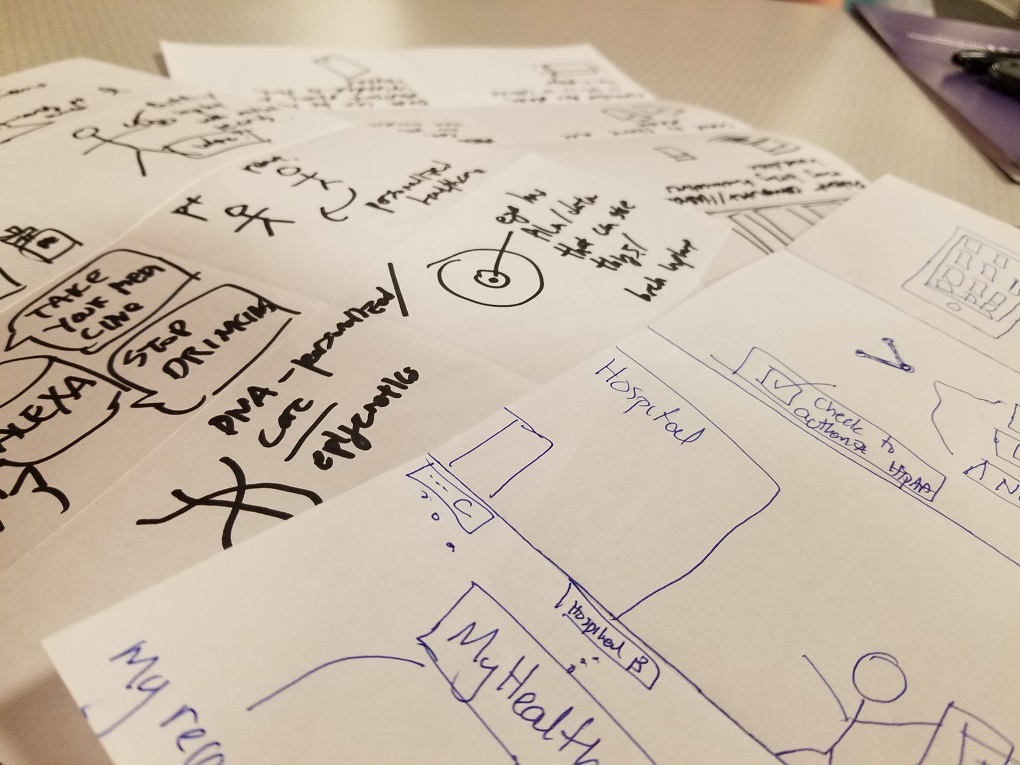

We applied this list of specifications to the different ideas we brainstormed in class the past week. I thought we had some good ideas, from an alexa integrated mobile app, to a buddy system, to getting more patient involvement. The ideas that shown through were the integrated mobile app, an alexa feature, and finally using a team system for staff between the OR’s to try and drive turn over time. In the final two weeks we hope to refine these ideas into a single valid concept that could have a big impact on UIH turn over time.

Adieu to Anesthesiology

John Marsiglio Blog

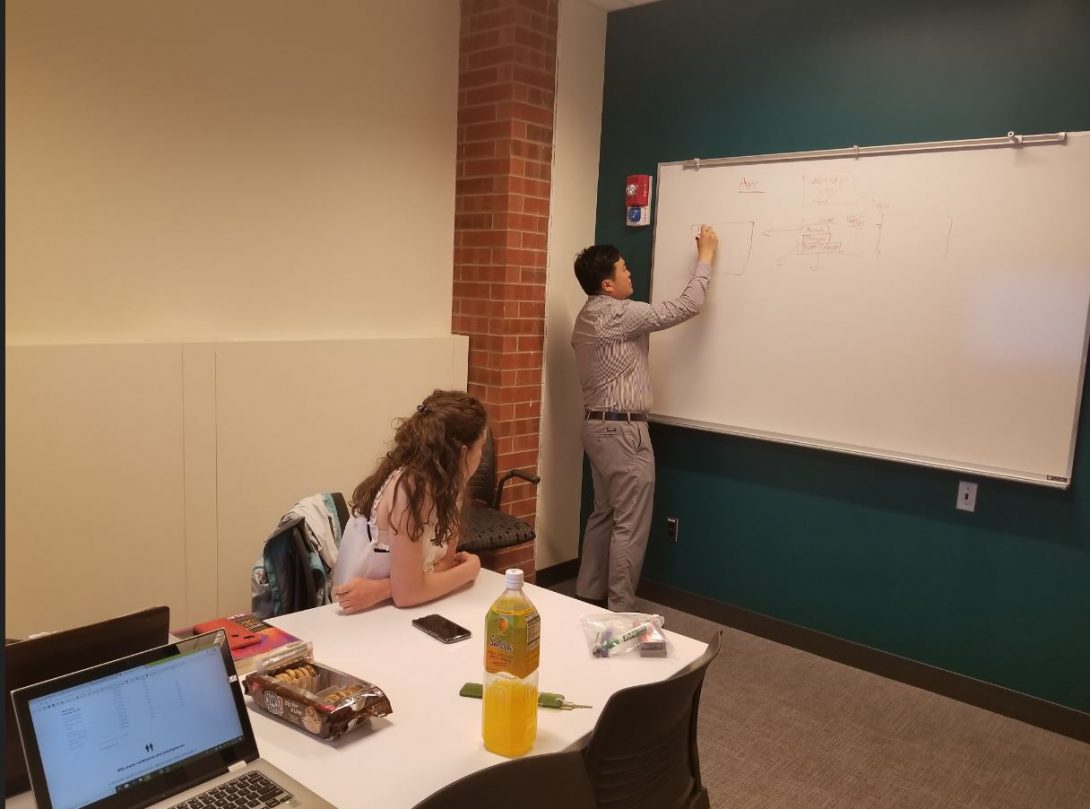

In our second to final week in anesthesiology Austin and I set out to hone in on how best our final project could help the anesthesiology department. This involved taking our list of specifications and figuring out how features of a mobile app (our highest rated idea), and an alexa app (our second highest rated idea) could address these specifications. We started out with about 8 core app features. These included ToT trackers, patient tracking, pre/post op task trackers with alerts that would be able to also keep track of time to return to the OR, and a feature to keep track of the ToT cause of delay. These features succinctly addressed the core specifications of our project. However, after more talking our list began to balloon to around 30 items. These extra 20 or so features didn’t directly meet the core specifications, but were all items that we thought “would be nice” based on the conversations we had with nursing and other OR interest groups.

We took this list to Dr. Nishioka and he gave us some really good advice. While it may seem to us that these extra 20 or so features would be nice, they could hurt the app. There are many people would have trouble adapting to new technologies, and more features doesn’t always make something better. Too many features will clutter the app, and make it more difficult for people to use. This was fantastic advice. Taking that in mind, Austin and I went back to the drawing board and talked about what were must haves in an app to address our core specifications, and what features, while potentially nice to have, would clutter up the app. Moving in that direction we cut back on our list of features to around 15 key features. Moving forward Austin and I hope to conceptualize our mobile app, along with it’s alexa capabilities, and present to Dr. Nishioka and members of the process improvement committee at UIH.

Closing thoughts: Overall CI has been a great experience and I’d like to thank Dr. Nishioka for being a fantastic mentor, Dr. Felder, Susan Stirling, and Kimberlee Wilkens for leading a great course, and finally my partner Austin Buen-Gharib for all his hard work, dedication, and being an all around great partner!

Asra Mubeen

Asra Mubeen Blog

Asra Mubeen Blog

The Beginning of my Journey

Asra Mubeen Blog

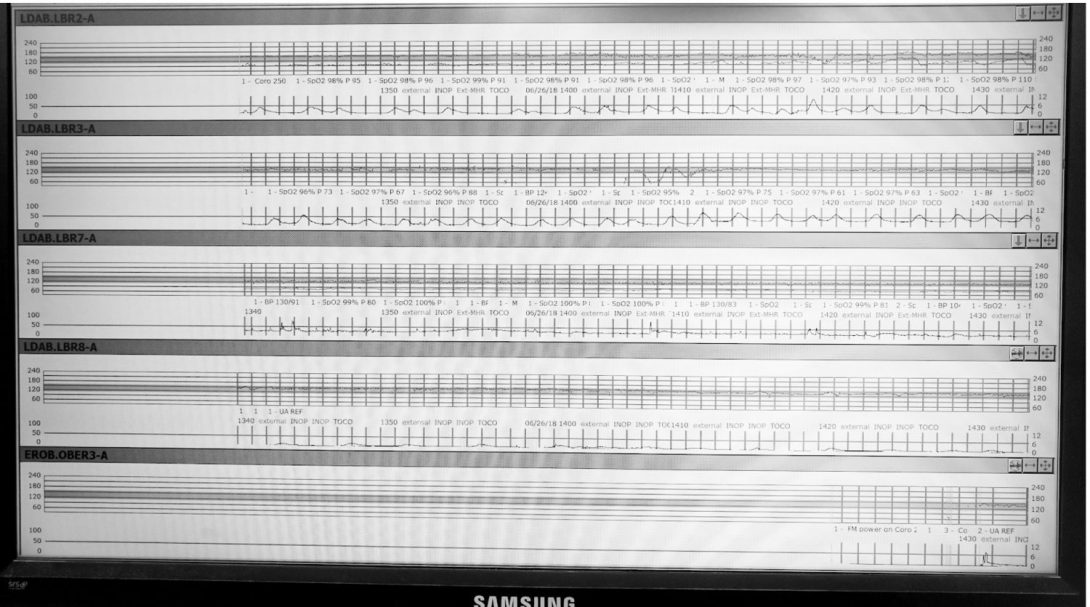

Wow! My first week at the OB ER was a very unique experience for me. We were observing Dr. Aparna Ramanathan and I had the opportunity to oversee some of the procedures. Dr. Ramanathan was very sweet in explaining to us the general medical terminology used in the OB ER. She showed us around the ER the first day and also the physician’s room. I noticed that in the physician’s room where the medical students, attending physicians, and residents were staying there were a lot of charts and dashboards posted. A white board covered with charts particularly stood out to me. These paper charts tracked the size of the cervical expansion during labor were heavily used by the entire medical staff in the OB ER. These contained helpful information but also since there were many users, it became unclear as to who was tracking what on the charts. I was also shocked that all these charts were on paper! I thought everything would be digitized by now.

Good vs Bad Design

Asra Mubeen Blog

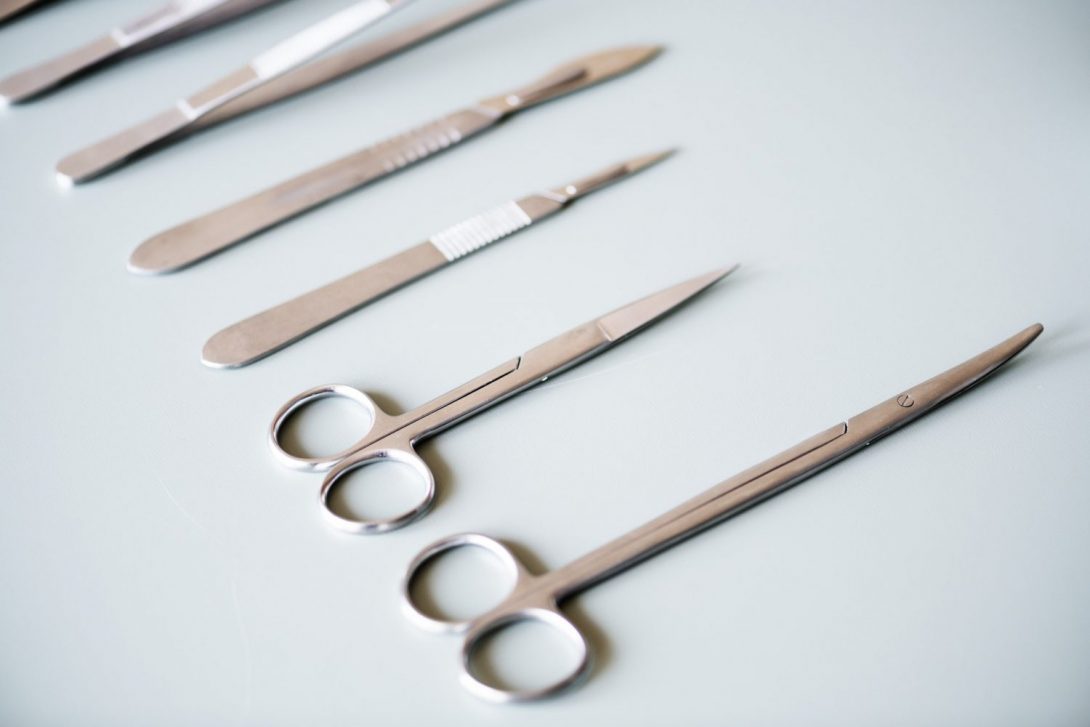

The next day at the clinic I had the opportunity to see Dr. Ramanathan perform a biopsy on a patient. At first, I thought the biopsy would be a long procedure but it turned out to be about 10 minutes with the help of the efficient tools the doctor was using. A particular tool stood out to me which was the punch tool (picture taken from Google Images). This tool was small enough to help with the biopsy of the pubic area. Instead of using scissors to make an incision in the skin to remove a fragment, the punch tool easily marked the skin area for the biopsy and with one easy insertion into the skin the circular skin fragment was removed for biopsy. The doctor did not need to use tweezers to hold or position the skin for the scissors to cut through. And of course, Lidocaine was used to numb the skin and silver nitrate was used to clot the blood from the incision. After the procedure, I asked the doctor more about the punch tool. She told me it was very simple for her to use and this tools also comes in different sizes for different types of biopsies.

My next shift was a night shift at the OB ER. During this shift, a medical student joined Dr. Ramanathan to help with the examination. I was able to watch the medical student perform a cervical speculum design. After the exam, the doctor gave me a brief history about speculums. Before plastic speculums metal speculums were used and even in some clinics today metal speculums may be used. The speculums used at the OB ER at UIC are made from clear plastic and have a built in light source. Instead of an on/off switch, the built-in LED turns on with the easy removal of a red tag. The plastic speculums are also disposable as compared to the metal speculums. The clear plastic helps examine the inner structures and it is also easily adjustable.

During night shifts, Dr. Ramanathan introduced us to “mini huddles”. I found this idea very interesting because these huddles helped the physicians and residents relieve stress and team bond. They switched off shifts and updated each other about the current patients in the room. They used one typed sheet of paper with a summary of all the patients in the OB ER during the huddle. These huddles were an excellent place where I applied the AEIOU framework.

A = Activities: Physicians provided patient summaries such as complications/risks, history, chronic illnesses, labor progress, and tests completed.

E = Environment: Resident’s staff room

I = Interactions: Physicians and residents update their charts and then sign off.

O = Objects: Charts created from Excel were shared and provided to physicians to quickly write down any notes.

U = Users: Physicians, nurses, midwives, and residents.

One particular bad design that stood out to me was the user interface of the ultrasound machine in the patient exam rooms. The controls on the ultrasound machine were disorganized with a tiny keyboard that made it hard for the doctor to type while wearing gloves. However, I was told by the medical staff that there are other ultrasound machines they use in the OB ER that work better and are easier to use.

Overall, I think this week was a blast! I really liked following Dr. Ramanathan around and she did a nice job explaining things around. I also met with my amazing partners to summarize some good and bad designs explored this week. I look forward to working with the team and coming up with a project design.

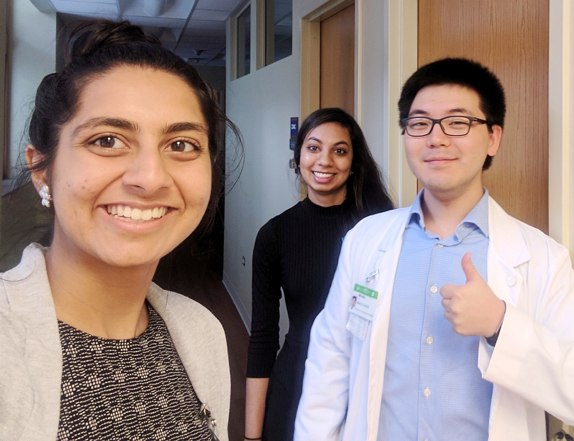

My First C-Section

Asra Mubeen Blog

The next day was a very eventful day for me. My teammates and I were each assigned a resident or physician to follow during the day so we could each see new procedures. I was in Labor & Delivery, Haley was observing D&E procedures, and Michael was at the OB OR. During the first third of my shift, I was called to watch an unscheduled c-section. When I was called by the physician, I was not prepared to see a c-section and when I was called I became a bit scared only because I did not know how to get ready for it! Luckily, a medical student took me under her wings and took me to a closet full of gear. I quickly put on the cap, shoe covers, and mask and then literally ran to the OR. I did not want to be in anyone’s way so I chose a corner to stand near the newborn baby’s bed. The surgery immediately started and within three minutes the baby was out! I was literally shivering when I saw this all happen four feet away from me. The baby was handed to the pediatric fellow and then placed onto his bed. The fellow was sucking the fluid out of the baby’s body when I noticed one of the nurse’s rummaging through the bed’s drawer. My eyes were on the patient as the resident was suturing the uterus. I heard the nurse say “we’re missing a small mask for the baby”. I faced the nurse and she asked me to quickly run to the other room and grab a small mask. I did not even know which room she was talking about but all I knew was the small mask was needed immediately for the baby. So I sprinted out of the OR and entered the nearest empty room I could find. I found the exact table drawer they were rummaging through, grabbed the mask, and ran out to the nurses. The baby was healthy and soon enough the father came to see his newborn son with tears in his eyes. I had mixed feelings as I stood there still watching the suturing. The suturing took the longest and overall the procedure was about 40 minutes long. Lastly, the mother was transferred to another bed and transported to another room. I walked out of the room and turned on my phone to check the time only to see many messages from my teammates about another cool procedure starting in about ten minutes. I knew this day would be eventful and busy at the same time and I loved it. (Photo courtesy of Michael Zhao)

Oophorectomy (story)

Asra Mubeen Blog

The procedure my teammate Michael called me down to see with him after my first c-section was an oophorectomy (ovary removal). This was the longest procedure thus far that I had watched. It was more than two hours. Michael handed me my gloves and shoe covers so I could quickly wear them and immediately enter the OR. When I entered the room, the general surgeon was there checking his laparoscopic equipment. We had about 15 people in the room including many medical students. For the first half of the procedure, the general surgeon would remove the gallbladder then the gynecologist fellow would remove the ovaries. The surgeons and the fellows were set up and the surgery began. The screen was turned on and the general surgeon explained to the students the major structures in the abdomen shown on the screen. Next, the general surgeon located the gallbladder and cut through the adhesions to remove it. Cutting through the adhesions was a slow process because the surgeon had to make sure that the correct adhesions were being snipped. During the surgery, Michael and I did observe a bit of a snafu. In the midst of cutting through the adhesions, the fellow from general surgery froze for 20 seconds. The attending turned his gaze from the screen to the fellow as she muttered “why is the gallbladder moving?”. The attending then looked down and yelled “the patient is sliding off the table!”. The attending covered the patient and the equipment with new drapes and within seconds almost everyone in the room was crowded near the patient to help adjust the bed. Meanwhile, Michael and I scribbled down notes as we watched the chaos in the OR. After ten minutes of adjusting the bed and scrubbing back in, the cholecystectomy resumed.

We noted that the bed was not really designed for an obese patient. When the general surgeon adjusted the bed to access the gallbladder, it was at a 45 degrees angle enough for the patient to slide down. The straps around the legs of the patient helped resist the patient from sliding left or right but not downwards. Some extra support right behind the hips or even behind the legs might have prevented the patient from sliding.

Later, the gynecology team took over. The gynecology procedure was shorter (about 15 minutes). They first had to identify the ovaries away from other structures. With our patient, only one of the ovaries was removed because the other ovary would require more adhesions to cut through. The attending identified the ovary as normal and recorded that cutting through the adhesions was not necessary. The other identified ovary for removal was then isolated from the internal structures by grasping it and pulling it away from the uterus. The suspensory, broad, and ovarian ligaments were clamped or ligated. The net pouch was inserted through the laparoscopic opening and the ovary was placed into it. The net pouch was then retracted and pulled out fairly easily. Errors could have occurred if the net pouch did not open large enough to fit the ovary. For this procedure this was not the case because the ovary is a small structure (about 1.5 cm in diameter). The other laparoscopic tools such as the grasper and camera were pulled out of the abdomen and the with the help of a medical student the fellow sutured the four laparoscopic openings. Local anesthesia was injected and the procedure was now over.

We walked out of the OR to hear the students and residents talking about the patient sliding off the bed. My next procedure would be another c-section in less than twenty minutes. I grabbed a snack on my way back up the hospital realizing that my shift would almost be over and I had forgotten to eat my lunch.

Second C-Section Observation

Asra Mubeen Blog

While observing my second C-section, I was finally able to put all my emotions aside and actually focus on the clinical environment and the medical device usage. This time during my observation of the C-section, I had an EMT student observing with me. The EMT student was not expecting to watch a C-section within the first hour of his OB ER shift. He was shivering because he was so nervous! I reassured him that it would be alright and that I will be there with him as well. This time I knew where all the gear was located for the surgeries and guided him to the closet full of masks and shoe covers. We got ready and walked in confidently into the OR. As soon as the fellow made the incision for the surgery, the EMT student turned to me and whispered to me that he was scared. I assumed that he was scared because he did not know what to expect and did not feel comfortable about what the surgery would entail. I explained to him that there was no need to be scared and that I will help explain to him what was happening. He felt a little relieved that he was observing with another student. I explained to him the steps of the C-section and pointed out a few things in the OR. Soon, the baby was out and he turned to tell me that he was no longer scared at all but super elated. I was happy that I was able to answer a few of his questions during the surgery. I did not get to finish watching the entire surgery because my shift had been over about an hour ago and my teammates were waiting for me.

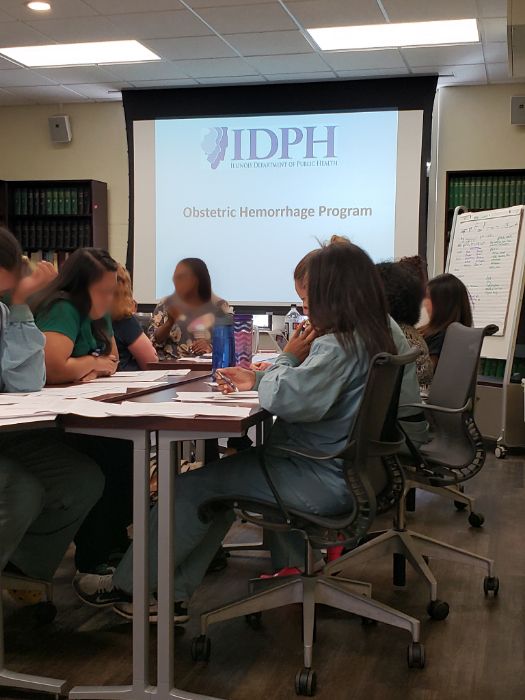

My team members and I have seen at least one C-section these past three weeks. One common thing that we noticed was that the residents and physicians struggle estimating the total blood loss at the end of the surgery. This was a rather lengthy process. After the surgery, the physician would count the number of laps used and their percent saturation. Next, they would read the amount of blood in the container (see picture) that they had vacuumed. Lastly, any blood on the drapes or dripped onto the floor was also accounted. One of the physicians told me that it was better for them to always “guesstimate” more blood loss than less. It was also difficult to truly estimate the blood loss because of other fluids like the amniotic fluid would also be factored into the calculation.

Our team began to discuss ways to make it easier for physicians to calculate the amount of blood loss. Dr. Ramanathan informed us that there was a postpartum hemorrhage program that the obstetrics department would be hosting. I volunteered to attend the program. Here, I learned more about the different ways the physicians handle blood transfusions at the hospital. I also got the chance to practice some suturing! At first, it was difficult for me to guide the curved needle with the needle driver. After I was taught a few techniques and how to properly hold the needle driver by a physician, my suturing improved and I was able to practice suturing on an artificial uterus. [I may have poked my finger with the needle during my first try ? ]

User Needs Identification

Our focus for this week was user needs identification. We found numerous areas at the hospital and clinic where we identified user needs. Our goal as a group was to address an observed problem among an audience in order to achieve an outcome. Continuing with the blood loss estimation process we can identify the user needs.

- A means of calculating blood loss during surgery for OR staff in order to avoid estimation errors. (very broad statement)

- A means of calculating blood loss during OB/GYN surgeries for OR staff in order to avoid estimation errors. (narrows down to type of surgeries)

- A means of calculating both accurately and efficiently the amount of blood loss during OB/GYN surgeries for OR staff in order to avoid future blood transfusion errors. (describes that calculations must be accurate and efficient and specifies future outcome)

Hysterectomy

Asra Mubeen Blog

We were scheduled to observe a 2.5-hour surgery with Dr. Ramanathan. However, this surgery ended up being about five hours. The surgery was a laparoscopic assisted hysterectomy. The resident informed us that it was not unusual to have a longer hysterectomy than expected. The patient was obese so it was difficult for the physician to access the uterus thus prolonging the procedure. We were able to observe the laparoscopic part of the procedure but our view was somewhat obstructed by the medical staff for the actual removal of the uterus. We did notice one recurring issue during the procedure. The attending used a weighted speculum that was difficult for the physician to position in the cervix. Also, the weighted speculum slipped out a total of four times during the procedure. Finally, a long arm weighted speculum was found in the other OR which was easier to position but even this slipped. Part of the reason for the slipping could have been the high BMI of the patient. Other than this issue the surgery was successful.

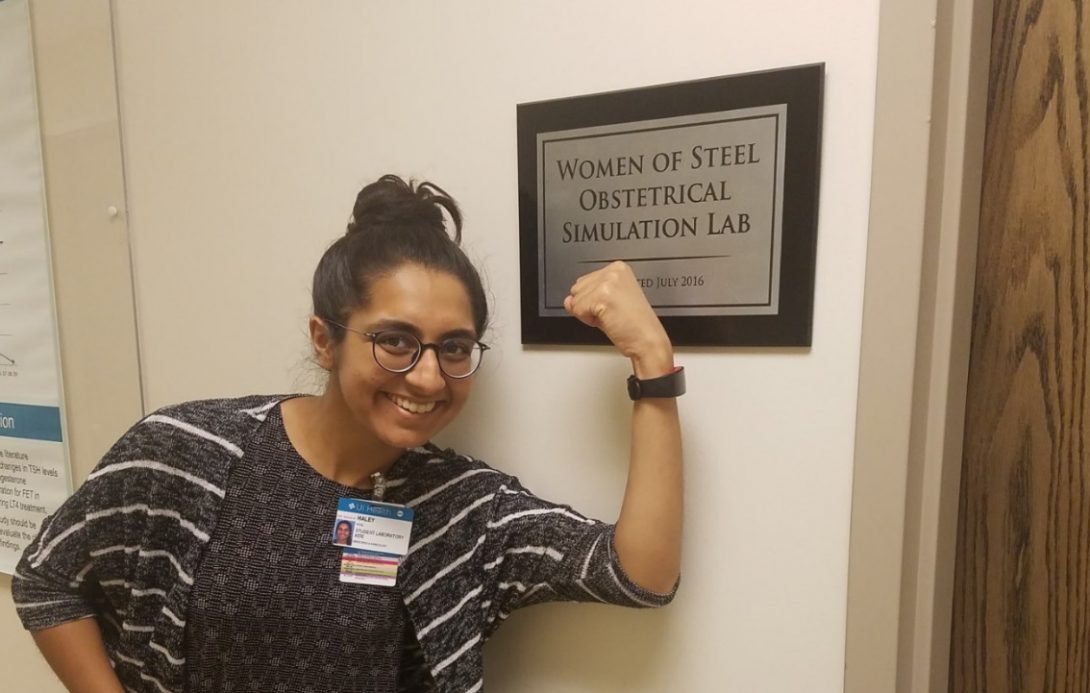

Obstetrics Simulation Lab

Asra Mubeen Blog

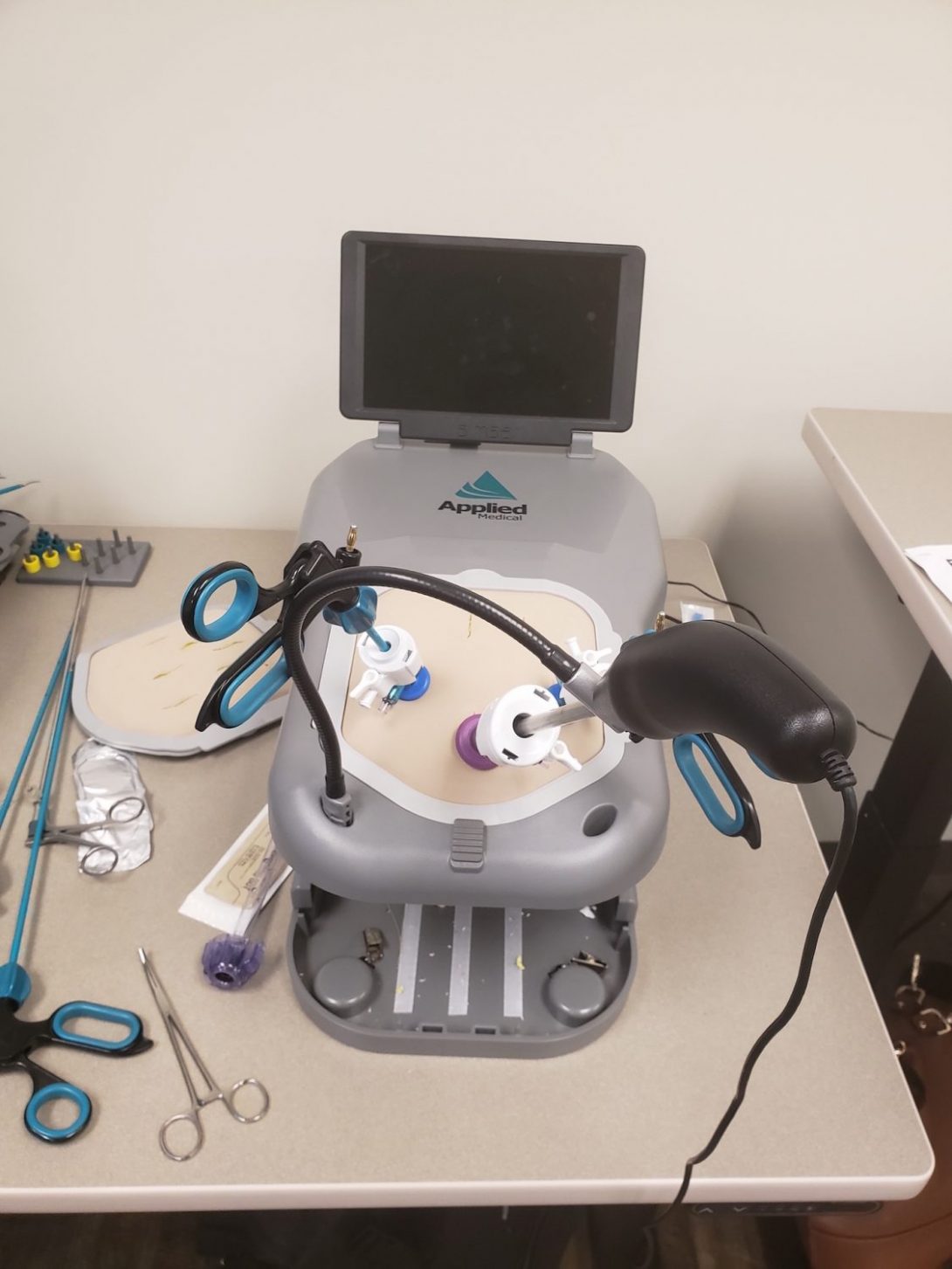

Dr. Ramanathan introduced us to a simulation lab across her office. Here, we had the opportunity to practice a few procedures with her help. My favorite procedure was using the laparoscopic tools to imitate a laparoscopic oophorectomy. The laparoscopy procedure was similar to playing a video game. You had to make sure that your hands and arms were really stable and your eyes were glued onto the screen. Even though when you’re observing a laparoscopic procedure it seems really easy but when you try it, you learn that it requires a lot of practice. In reality, you are conducting the procedure over a very small operative field and your dexterity becomes important. I really enjoyed this hands-on practice and it became addicting to keep trying until you had the perfect grasp.

Ultrasound with Dr. Zamah

Asra Mubeen Blog

Today at the clinic we were assigned to work with another attending, Dr. Zamah. He is one of the most energetic physician I have met so far. He was excited to hear that we were working on designing a project to improve the OB/GYN practice. He suggested many ideas to us for our project. We had the opportunity to observe a few SIS tests that he performed. I was surprised that a simple solution like saline was used during the test to help make the ultrasounds reports clearer to read and observe any abnormalities. Finally, it became easier for me to understand ultrasound reports after he pointed a few things to us.

Week 4: Design Specifications

Asra Mubeen Blog

This week we began to narrow our ideas to finalize one project we would work on for the remainder of this program. We had a meeting with Dr. Ramanathan at the end of the week where we presented our top 20 need statement ideas to her. She chose a few of those ideas that she preferred. Then, as a team we selected a need statement we were all interested on working.

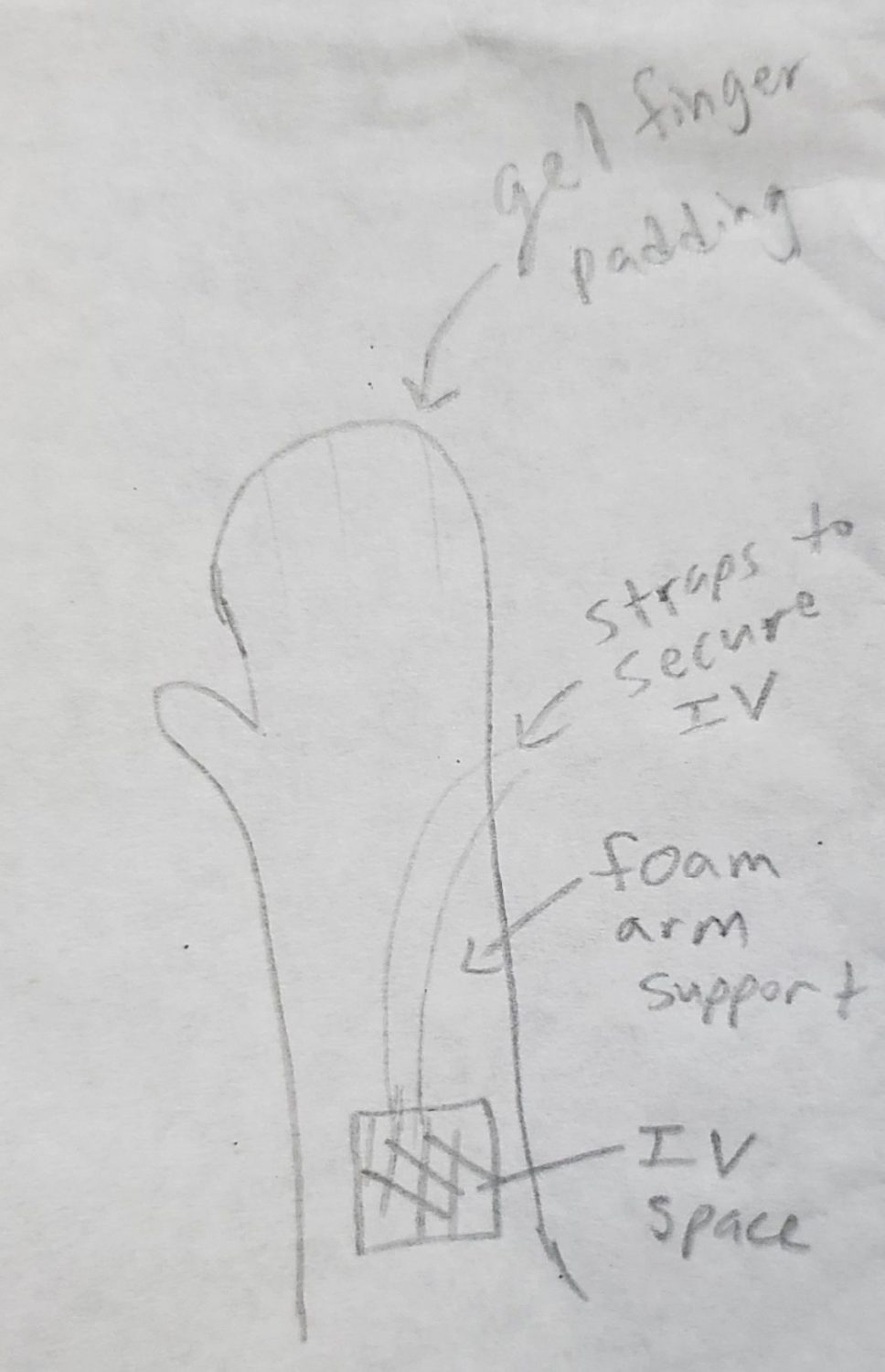

Typically, before a GYN surgery a few minutes are spent just setting up for the procedure. These valuable minutes can be used elsewhere during the procedure’s set time. The longest part of the set-up is the upper limb support. The medical staff wraps the patient’s arms with gel, tape, towels, and lots of egg-crate foam. This process is long and many different materials are used as listed. We also noticed that it is not always effective either. During the procedure, we have noticed that the wrapping unravels causing the upper limbs to slip off the bed.

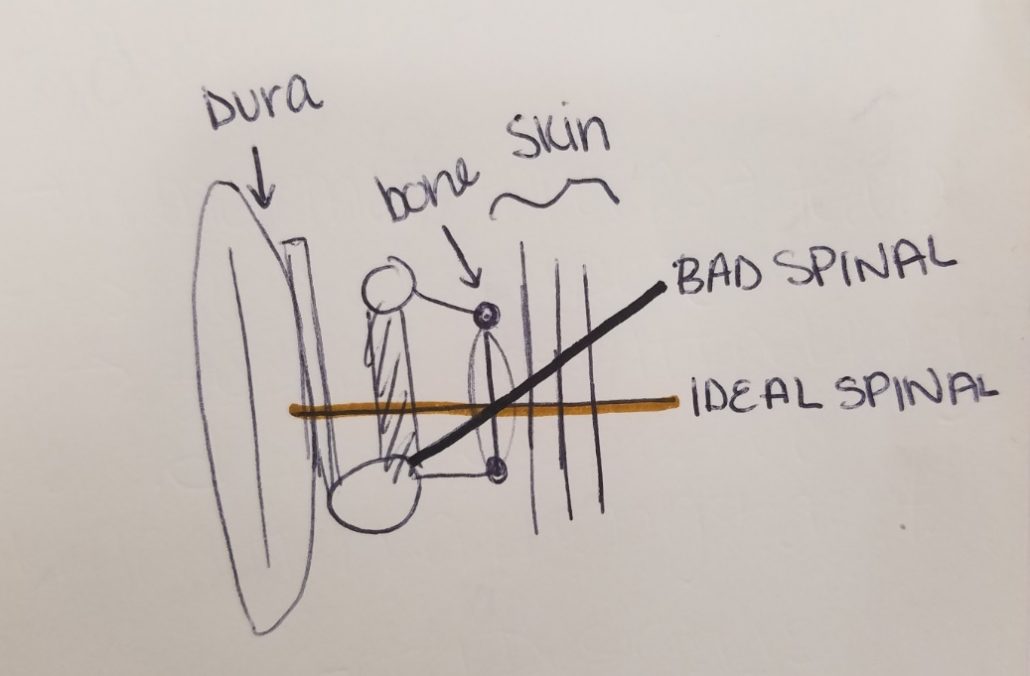

We discussed a few specifications as a group for this need. Our design should be unobtrusive meaning it should provide easy access to IV and is not an obstruction during the surgery. It should also be intuitive enough for a faster set-up. More importantly, it should be effective. The design’s purpose is to prevent skin injuries and minimize pressure points during lengthy procedures. We sketched a few designs and concluded that the mitt design would work the best. [see sketch for design]

Week 5: Conceptualize

Asra Mubeen Blog

Even though we have already decided on a project to focus our designing and prototyping, this week we still continued to shadow Dr. Ramanathan and kept an open mind. At the clinic, we noticed that the computers were unusually slow that was stressing Dr. Ramanathan. I remember her even muttering “they are painfully slow today and my patients are waiting for me”. I wish we could help out with the computer loading situation. It was a good thing that the patients that we saw at the clinic this week were here for quick visits. One patient just wanted a referral and another one wanted to discuss about a pessary (device used to help with uterine prolapse by holding the uterus up when pelvic muscles are weak–usually weakened by obesity or after many deliveries). I also got the chance to observe some LEEP procedures, pap smears, and colposcopy. From my observations, I can say that these procedures are very PAINFUL. I heard patients yell phrases like “I already want to quit” or “stop, please stop!”. The residents explained to me that only some anesthesia can be used because these are short procedures and sometimes it becomes difficult to reach certain areas of the pubic area to anesthetize. Lastly, Dr. Ramanathan taught me how they insert IUDs at the clinic using a demo kit. I then practiced on the demo kit a few times with the help of a medical student.

Our last day at the OR, we observed a tubal ligation. This was a 30-minute procedure and nine minutes of those were spent on setting up the upper limb support. Gel, blanket, and foam were used to wrap around the arm. They even had to redo the right arm because the first time it was not positioned correctly. This OR observation proved to us that there was definitely a need for our design. We spent the remainder of our week discussing about our project design and the materials needed for it. We went through a few iterations with Dr. Ramanathan before we finalized a design.

Last Week NOOO

Asra Mubeen Blog

Sadly, this is our last week of the internship. Our team spent most of the time in Labor and Deliver testing and adjusting our prototype. We discussed about the materials we would use and explored some material types at the innovation center. Our prototype is ready to be presented. I had an amazing time with my team observing procedures and identifying user needs in the OB/GYN department. I am really glad that I had the opportunity to be a part of this amazing program. Special thanks goes to Dr. Ramanathan for joining this program this year and having us join her! She has been really supportive and resourceful during this internship in making sure that we understand enough of the medical terminology to understand each procedure. Also, thanks to all the mentors of this program who were really helpful in teaching us about the designing process! (Photo courtesy of Michael Zhao)

Lara Nammari

Lara Nammari Blog

Lara Nammari Blog

Week One Notes

Lara Nammari Blog

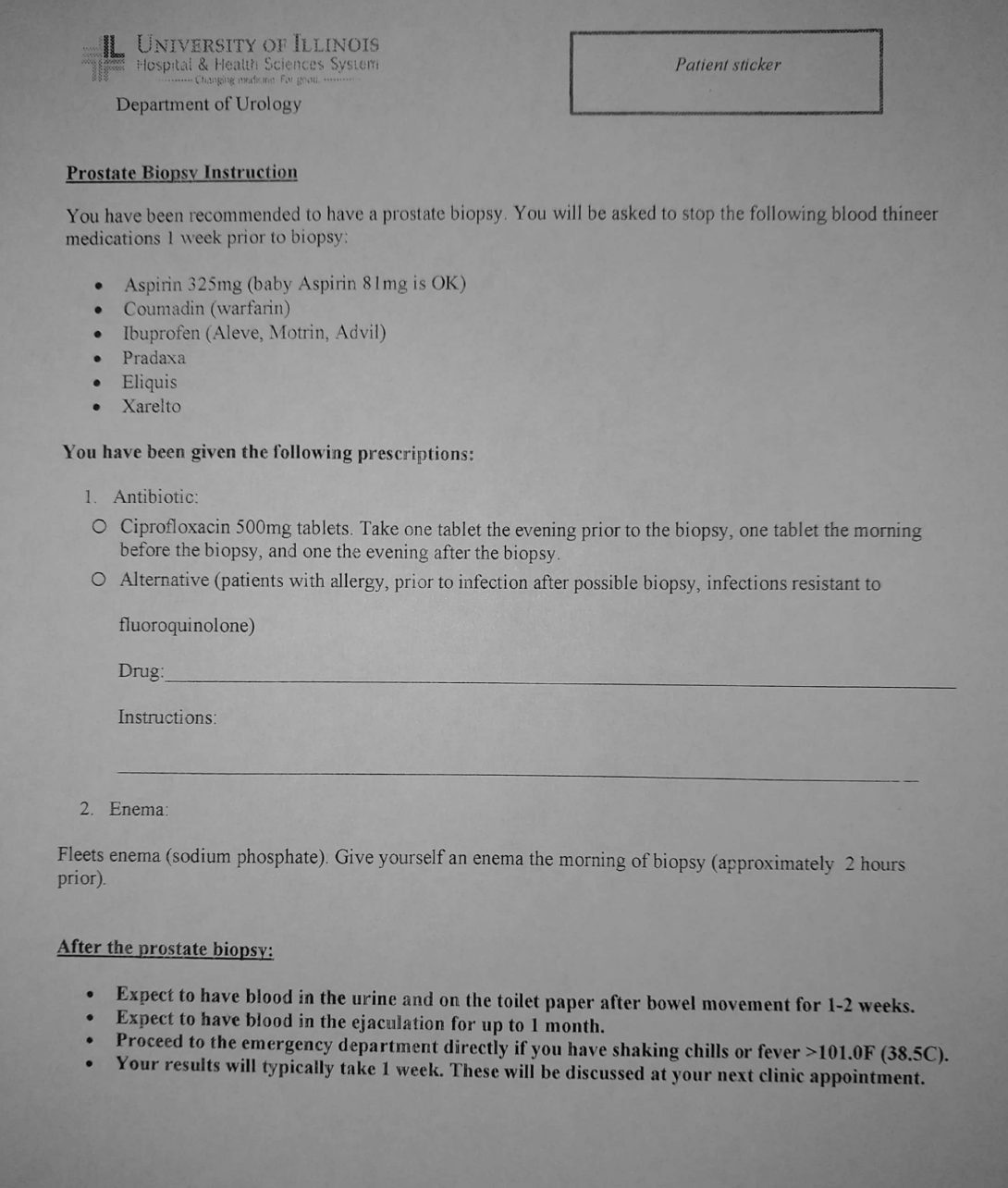

This week in Urology I spent most of my time in the clinic. There were routine procedures that patients weren’t properly preparing for. For example when a patient is scheduled for a prostate biopsy I noticed that they weren’t taking the antibiotics or preforming a fleeting enema. This causes delays in the clinic. The delays resulted in other patients waiting an hour or more to see a doctor, the doctors skipping lunches, and the waiting room being crowded. This can cause stress for doctors, patients, nurses and front desk associates.

The directions for the biopsy are written in bullet points. The patient is supposed to take one antibiotic pill the evening before the procedure, two hours before the procedure and the evening after the procedure. When I asked the doctors why the patients don’t prepare properly I was given a few answers.

- The patient forgets to pick up the prescription for the antibiotics

- The patient thinks that a prescription is needed for the enema and so does not get one over the counter

- The patient takes the incorrect amount of pills

- Ex. The patient took two pills the night before and one before the procedure, so there are none left for the evening of the procedure

- The patient forgets to take the antibiotics

- The patient has so many appointments they forgot why they have an appointment

This is just the doctors’ perspective. Maybe the patients were too uncomfortable using a fleet enema? In the next few weeks I will try to find out the patients perspective. I think there could be an easy solution to this problem that has the potential to make the clinic run more on time. Dr. Abern believes that a step by step animation would help patients better understand the instructions. We will try to create one and test it in the clinic.

Week Two Notes

Lara Nammari Blog

I noticed that during transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) surgery the attending alerted the nurse that the irrigation fluid bag was empty. This was a problem since TURP requires irrigation fluid on demand. After getting feedback from a surgeon, he felt that the nurses should pay more attention to the level of fluid in the bag. However, I want to spend next week storyboarding with some OR nurses to see what their experience in surgery is like. Once I have a complete understanding of what is going on in the OR it will be easier to identify pain points leading up to the irrigation bag being replaced.

As a team we created a storyboard using the patient perspective of a prostate biopsy. I bolded the pain points.

-

- PCP appointment

- Doctor misdiagnosis

- PCP referral to specialist

-

- High PSA levels

- Abnormal prostate exam

-

- Insurance coverage

- Medical records requests

- Call specialist to make appointment

- Weeks/months in advance

- Long waits on phone

- Resident performs prostate exam

- Uncomfortable patient

-

- Attending decides if prostate biopsy is needed

- Biopsy can cause or worsen erectile dysfunction and nocturia

- Infection risk

- Information about biopsy is presented

- Medical jargon

- Form given to patient about prep instructions

- Patient makes second appointment

- Scheduled a month after initial appointment

-

- Picks up antibiotic and enema for biopsy

- Take one tablet the night before

- One tablet 2 hours before with enema

- One tabet the night after

- Complicated steps

- Patient forgets to take tablets

- Takes too many tablets in a day

- If not prepared cancel/delay appointment to avoid infection

- Picks up antibiotic and enema for biopsy

- Show up to clinic for biopsy

-

- Change into gown/position body

- Uncomfortable/vulnerable

- Receive local anesthesia and probe/ultrasound inserted

- Painful

- Hard to navigate probe

- Sample taken

- Loud alarming sounds

- Change into gown/position body

- Ice area and rest for 48 hours

- Blood in urine, bruising

- Schedule appointment for pathology report

- Wait at checkout desk

- Discuss surgeries and treatment if pathology shows cancer

- Lack of pathology explanation

There are quite a few pain points for prostate biopsy that we will have to explore in more detail about why those pain points occur.

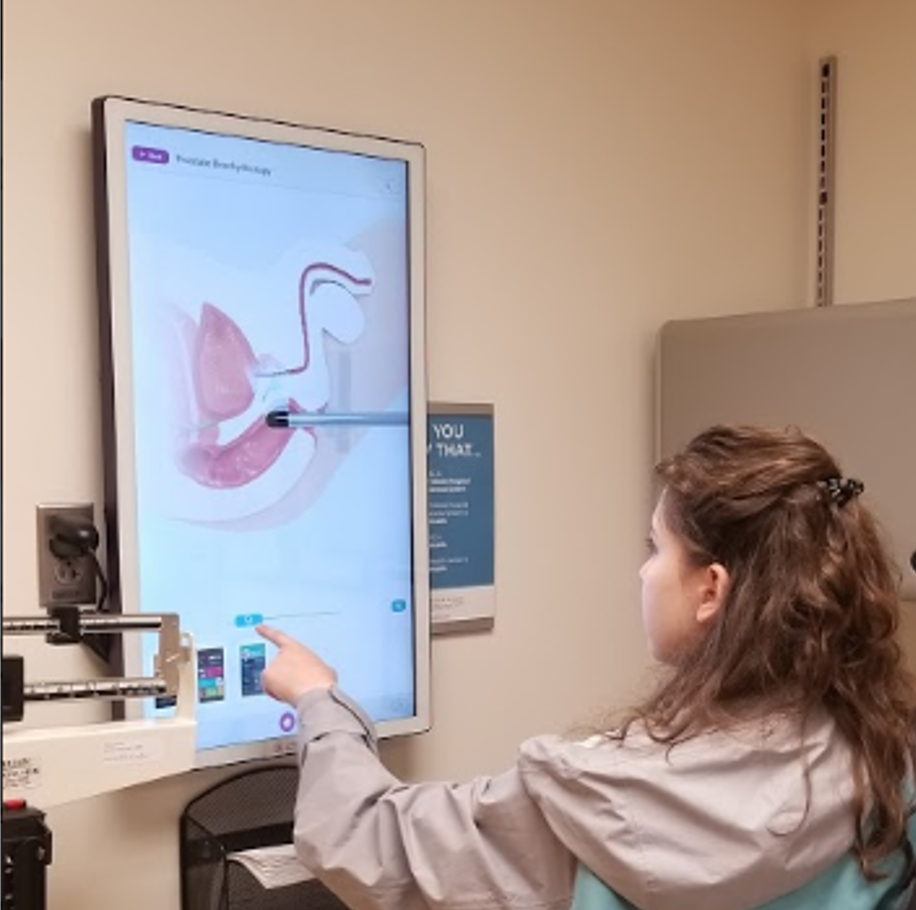

I noticed that there was a touch screen that showed the anatomy of any body part as well as an animation of popular procedures. One of those procedures was a prostate biopsy. I think it is a great tool that will make it easier for patients who don’t understand medical jargon to understand their own conditions and possible procedures.

The picture I attached above is the process of a biopsy explained using the touch screen tool.

Week Three Notes

Lara Nammari Blog

This week we focused on creating and revising need statements. This was difficult for me as an engineering student. A need statement cannot be solution driven in order to accurately assess the problem. As an engineering student I like the creativity that comes with solution designing. Lucky for me the urology department gave a lot of feedback and advice on our need statements.

I made a realization that was unsettling for me. When you are in the clinic it is easy to get stuck in statistics and technicality, rather than the emotions of the patient. We assumed that the reason the patient wasn’t adhering to prostate biopsy prep was due to confusion of instructions. I totally forgot how the patient must feel when they are told they need a biopsy since biopsies are used to diagnose cancer. I forgot the human emotion side of medicine.

Fortunately I was able to attend a group therapy session for cancer patients. It was hard to hear their experiences, but I learned a lot about the patient side of cancer that helped balance our need statements. The patients all agreed that they didn’t remember the appointment where they were told they had cancer. They were still processing the idea of cancer while the doctors were trying to discuss treatment options.They also all agreed that group therapy really helped them feel empowered and learn more about how to deal with the different aspects of being a cancer patient.

This lead us to the need statement:

A better way to lead men with positive prostate biopsy than standard of care that provides higher usage of social services, mental health counselors, and support groups.

Being in contact with people who can help patients cope with the diagnosis can improve the quality of life for cancer patients.

Week Four Notes

Lara Nammari Blog

This week we focused on creating high level specifications for our need statement. We decided to explore changing the way medical records are changed between clinics. We first observed this issue when in the clinic, the MAs must requested medical records to be sent over from a primary care physician before scheduling appointment at the urology clinic. The missing medical records resulted in delay of the patients care. One of the physicians said that they will receive the entire patient history file from the previous physicians office and the urology physicians then have to spend time filtering through those irrelevant records. The Miles Square clinic had received a patient history file 200 pages long. One of the Miles Square MA said that it can take a week to get medical records faxed over to the urology clinic. We also checked out the neurosurgery department to see if this process of getting medical records. The neurosurgery team said that the patients bring in their own imaging on the day of appointments. We thought there had to be a better way of transporting records.

Our need statement: A better way to obtain relevant historical medical records for new patients as measured by decreased appointment cancellation/delays and need for repeat imaging.

As a team we discussed the high level specifications for this problem.

- HIPAA Compliant

- Does the solution adhere to HIPAA

- Reliable

- Is the solutions reliable to present the information as needed?

- Security

- Does the solution work interoperably between different healthcare systems

- Ease of Use

- Is the solution easy to use

- Economically viable

- Is the solution economically viable

- Accessibility

- Is there equipment needed to access the data?

- Storage

- Does the device have enough storage?

Week Five Notes

Lara Nammari Blog

This week we further developed two ideas and presented to the UroLab to get feedback. I also presented the ideas to the providers in the urology department. I really appreciate this opportunity to identify problems and come up with solutions while getting immediate feedback from the user. We are learning that it is an iterative process. Most of my time in this internship has been focused on identifying problems and writing great problem statements. The solution comes out of the problem statement, so it must be effective.

Divinefavor Osinloye

Divinefavor Osinloye

Hello! My name is Divinefavor, and I’m currently 21-years-old. Also, I’m a first-generation, Nigerian-American student, currently about to complete my senior year in bioengineering for my bachelor’s degree at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). My parents won a visa lottery two months before my twin (Prosper) and I were born! We flew (still in our mother’s womb) to America – just in time to be born as natural-born U.S. citizens. Moreover, we were born in Cook County Hospital, now “John H. Stroger, Jr. Hospital of Cook County”, in Chicago, Illinois on May 8th, 1997. Our younger brother, Victor, was born a year and a half after my twin and I, and our littlest brother, Praise, was born about four years after him. We moved from our apartment in Noble Square to our house in Romeoville in 2002, after our littlest brother was born; our father wanted us to have better opportunities in education, as well as a better schooling environment (As you can see, I like to use a lot of parentheses in my sentences)!

Outside of my classes and internships,

I enjoy cooking Nigerian and American dishes, I play the trumpet and some piano, I compose my own television theme songs (and love songs), I enjoy watching inspirational real-life and animated television shows and movies, and I’m a big Jesus’ boy.

That being said, I’m very excited to participate in the Clinical Immersion Program because I get to receive insight from real doctors, nurses, and bioengineering companies. I love to be creative in anything I’m doing, and I hope for that creative energy to transfer over to bioengineering designs. Given the opportunity, I also hope to learn from my peers in this program.

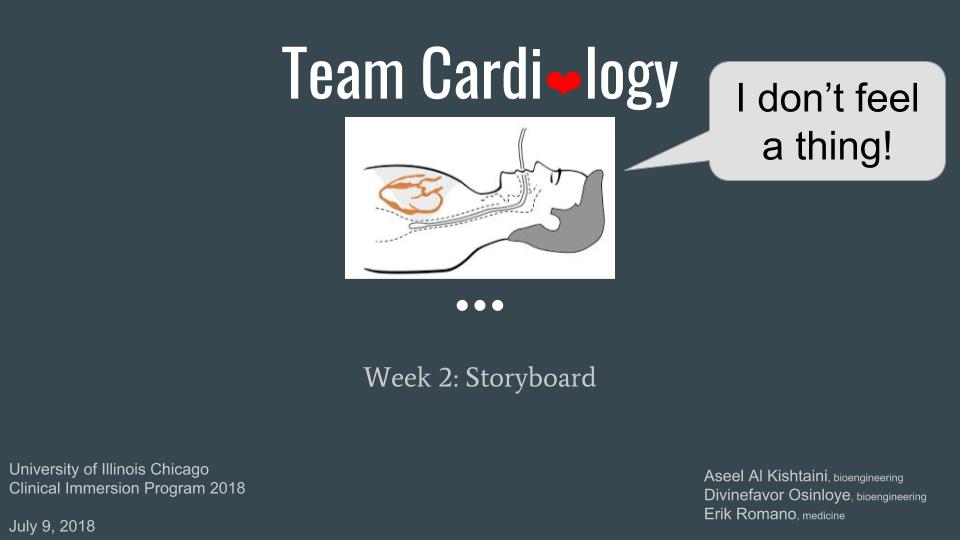

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Week 1 Blog (Long version)

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Introduction

This past week, I have been directly exposed to about three or four live surgeries in the department of Cardiology per day. Some of the surgical procedures that took place included the Trans catheter Value Replacement (TAVR) Procedure by Dr. Grooves, Atrial- Flutter Ablation by Dr. Wissner, Chronic Total Occlusion (CTO) by Dr. Zippor, and the “Left and Right Heart Coronary Artery Cath” by Dr. Grooves. I was also privileged to have the opportunity to dress in scrubs and a lead coat, and even be able to stand next to the doctor as he was operating with the patient.

“You look like one of us,” a nurse remarked.

However, there were some operating rooms that were tightly spaced, so I did not want to the doctor while he was performing the operation. Therefore, so the nurses assisting the doctor would answer my questions during the live surgical procedures. However, the doctors were super nice and were willing to answer my questions once they had finished. Dr. Wissner, my mentor for the Clinical Immersion Program, even explained step-by-step what he was doing as I stood directly next to him. I really appreciated him for this, as he also let me ask any question I wanted.

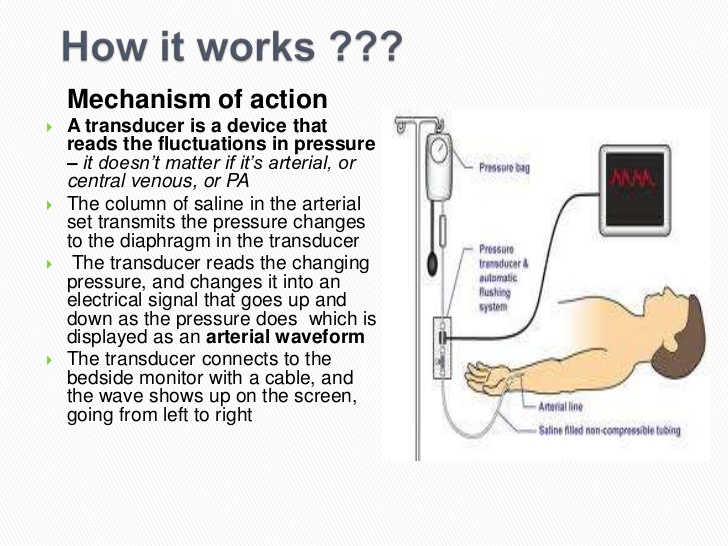

Activities- What are people doing?

As you can see, there are many surgical procedures that can done in the Cardiology labs. That being said, cardiologists generally works hand in hand with an assistant doctor the operating room during a given procedure. Moreover, two nurses help the doctor to unseal or wash the materials (unique catheters, pipes, guide metals, scissors and more). Also, one or two anesthesiologists attend at to the patient, monitoring his heart rate and blood pressure, as well as encourage the patient to relax and that he is “doing a great job”. Two more nurses are behind a window, in what I call the “monitoring room”. Here, the two nurse document any material that is used or exchanged, as well as info on the patient (ex. Pulmonary Capillary Wedge). Furthermore, they record info about the patient’s stress test, the patient’s diagnosis, and the doctor’s surgical technique into a computer called “Camtronics”.

Each surgery could last more than an hour, and there were times that I had to shift my feet. Thankfully, the nurses were nice and brought me a stool to sit on! Therefore, one would see nurses resting on stools from time to time.

Once the surgical procedure is completed, the doctor collaborates with the two nurses in the monitoring room and writes a report on that surgical procedure.

Environment- Where are they doing it?

Moreover, the primary settings of operation include the Echocardiogram Lab, the Catheterization Lab, the Operating Room and the Electrophysiology Lab.

Interactions- How are people/artifacts engaged?

It took quite a few surgical cases to finally have an idea of what a cardiologist is generally trying to do, but after asking the nurses, I’ve been able to conceptualize a general structure of interaction for each surgical case:

Two nurses roll in the patient, place him on the procedure table, shave his pubic hair, wipe his body, cover a green blue sheet on his chest and pubic hair, place blue sheet covering on the body, prepare sterile materials for the doctor, dress the doctor, and protect themselves with a heavy lead sheet. Then, an X-ray (or ultrasound) device hovers over the patient’s chest area.

“I make sure the doctor has everything he needs”, said one nurse, “and that he is not kept waiting.”

The doctor’s hand, for the most part of the operation, is always “glued” to the catheter.

The anesthesiologists are attending the patient at his head, ready to administer more sedative medicine in case the patient has pain, as well as encourage the patient.

Objects- What artifacts do you observe?

There are objects that are commonly used in all these labs. Specifically, the Camtronics is a dynamic computer device takes note of the patient heart rate, blood pressure, SpO2 concentration, and more. Moreover, the two nurses in the monitoring room can easily record every intervention, diagnosis, exchanged material, and more in Camtronics, since Camtronics has a menu-list feature for the nurses to choose from. These nurse also speak through a speaker, in which they are able to communicate with the doctor in the operating room, and they are able to see the X-ray of the snapshots of the patient’s heart during the doctor’s intervention.

Moreover, the doctor has a six computers (in a two by three format) where he can view the X-ray of the patient’s heart, which can be detect from an X-ray/ultrasound device hovering over the patient’s chest. He uses some type of catheter to access the entire aorta and coronary arteries, and he has tablet of control handles that he can turn to move these devices and the table of his patient to a desired angle atrium and ventricles.

There also were notable “good” designs and “bad” designs. An example of good designs were catheters. Specifically, Dr. Wissner demonstrated some of the cool features of his ablation-catheter during the Atrial-Flutter Ablation Surgery. After this point, I was able to get a solid understanding of how a basic catheter works: Each catheter has a guide metal that can bend and flex in a desired direction by the push of a lever. On the front of the tip of the catheter is a “balloon”. When this balloon is inflated, it dilates the blood vessels. Finally, each catheter has a “cobalt-chromium” stent that basically holds the blood vessel open so that blood flow is not constricted and blood clots will not form. Specifically for the Atrial-Flutter Ablation Operation, Dr. Wissner used an ablation-catheter. The patient had a right atrium that vibrated so quickly that the blood flow “looped” endlessly, barely even passing into the left ventricle. Therefore, Dr. Wissner used the ablation-catheter, which had electrodes on its tip that could release heat to burn the tissue of the right atrium walls. He used it to draw an ‘ablation line” on the lower wall of the right ventricle. This was in order to prevent the abnormal blood flow from reoccurring again. Moreover, Dr. Wissner said that this ablation line would disturb that blood flow loop and cause the blood to flow to the normally through the atrial valve. Also, two representatives from Boston Scientific were in the “monitoring room”, and they showed us their company’s computer mapping system that was recording all the probing movements that Dr. Wissner made with his Ablation-Catheter in the patient’s right atrium. By the time Dr. Wissner was finished with the surgical procedure, there was a 3-Dimensional model of the patient’s right ventricle and surrounding tissues! Relative to the Ablation-Catheter, the Glide Scope is a “bad” design. For example, my group and I witnessed two Transesophageal Echocardiogram procedures this past week, in which a specialized probe containing and ultrasound transducer was injected into the patient’s mouth, and the camera on it allows the doctor to view what is happening in the heart, since the esophagus “sits behind the heart”. On the first occasion, however, a doctor attempted “eight times” to insert the Glide into the patient’s mouth. However, the Glide failed to enter the esophagus, so the procedure was aborted. “Number one rule in medical school- cause NO harm!” the doctor said. This doctor claimed that that one of the factors that lead to failure of the procedure was due the patients anatomy of her neck (she was obese and had excess adipose tissue in her neck obstructed the glide from passing through).On the second occasion of the Transesophageal Echo, however, there was still difficulty with inserting the glide into the patient, who was much “thinner” relative to the first patient. As a result, the supervising doctor had to intervene. He managed to insert the device, but a noticeable amount of saliva mixed with blood came out of the patient’s mouth.

Users – Who is in the environment?

To reiterate the previous paragraphs, there is one doctor, who works hand in hand with an assistant doctor. Together, they collaborate with one or two anesthesiologists, to notify whether the patient is having pain or is keeps moving. Two nurses help the doctor to open and wash the materials (unique catheters, pipes, and more) he needs. Also, one or two anesthesiologists attend at to the patient, monitoring his heart rate and blood pressure, as well as encourage the patient to relax and that he is “doing a great job”. Two more nurses are behind a window, in what I call the “monitoring room”. Here, the two nurse record info about the patient’s stress test, the patient’s diagnosis, and the doctor’s surgical technique into a computer called “Camtronics”.

Highlights and Conclusion

A highlight of this week was the CTO procedure. It took place last Friday, and I was intrigued to find out that very few doctors are specialized to perform this procedure (to be explained on another blog post).

Another highlight was getting to meet Dr. Rose Gonzalez, who showed us cool bioengineering pace-makers that she diagnoses to her patients. Some of the companies of these pacemakers include Boston Scientific, St. Jude and Medtronic. With that being said, Dr. Gonzalez was very welcoming; she showed us a lot about her work, and she also was very kind and down to earth (plus, I think she just finds my group and me adorable!)

Overall, I have learned a lot this week about how the flow of the heart works, and all the nurses and the doctors were nice and willing to answer my questions. I look forward to the next week, now that I have a better idea on when to engage and ask questions, and when to just watch the procedure.

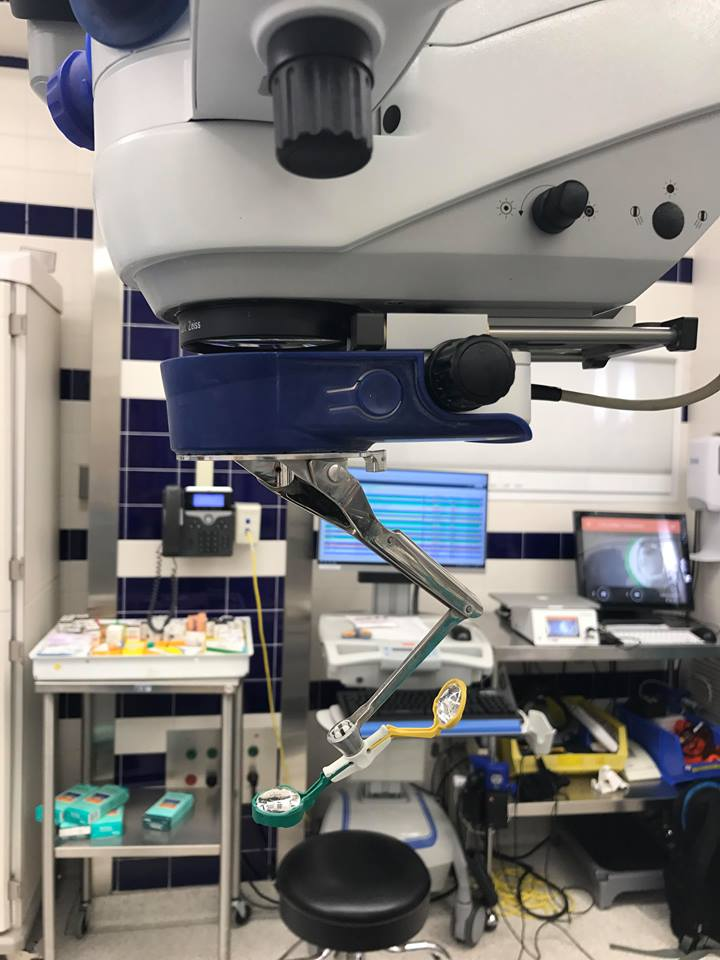

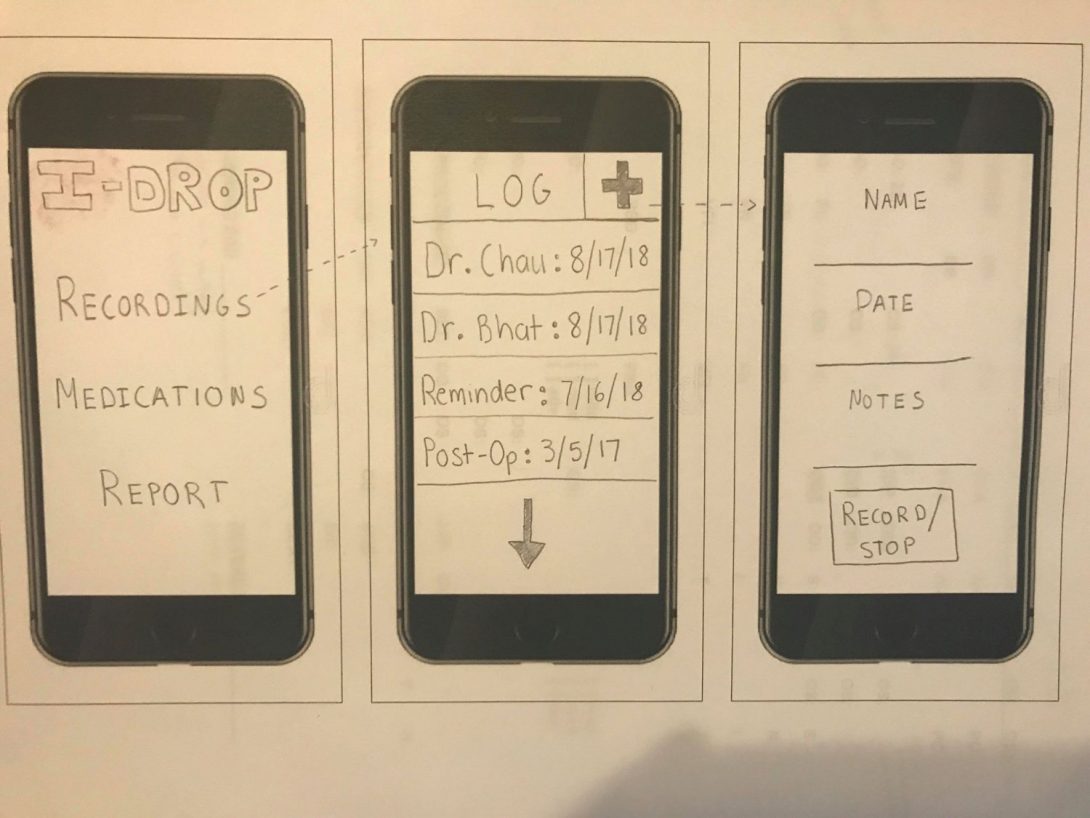

Week 2 Blog (Storyboard of a Typical Right Heart Catheterization Procedure)

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Here is my storyboard based on the observations I made last week of Right Heart Catheterization procedures. These procedures took place in the Catheterization Laboratory of the University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System:

One-Sentence Summary of Problem: Patient is diagnosed with heart failure.

One-Sentence Summary of Solution: Right Heart Catheterization Procedure is applied to observe the patient’s heart pressures.

Storyboard

Step One: Remove any jewelry or objects that will interfere with procedure.

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Links Cited: https://www.smarthomekeeping.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/measuring-metal-watch-band.jpg

Pain Points:

- Patient may not want to remove “good-luck” charms or religious objects that would help them to remain calm during the procedure

Step Two: Change into hospital gown and empty bladder

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

(2)

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Links Cited: (1) https://i.ytimg.com/vi/g6PEzrOQzdo/maxresdefault.jpg

(2) http://coresites-cdn.factorymedia.com/twc/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/female-toilet-uti-icon.jpg

Pain Points:

- Patient is concerned for his or her privacy.

- Patient may have difficulty moving urinary (or bowel) system

Step Three: Anesthesiologist will apply intravenous (IV) line in patient’s hand

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Links Cited: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0d/ICU_IV_1.jpg

Pain Points:

- The anesthesiologist may have small space to work with (usually at the head of the patient), since the doctor needs as much space as possible for the procedure

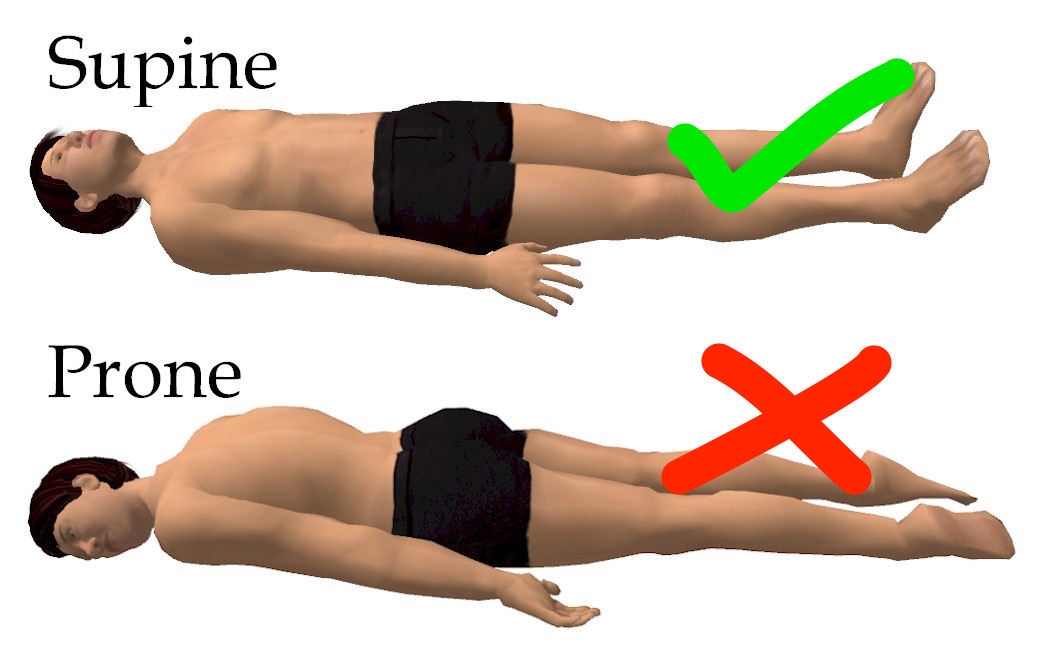

Step Four: Patient should lie supine on back on procedure table

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Links Cited: https://beyondgoodhealthclinics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/sleep_posture_brisbane_supine.png

Pain Points:

- Patient may experience back pain as he or she lay on procedure table

- On one particular patient had an issue with her sciatic nerve, so she felt excruciating pain as she lay down

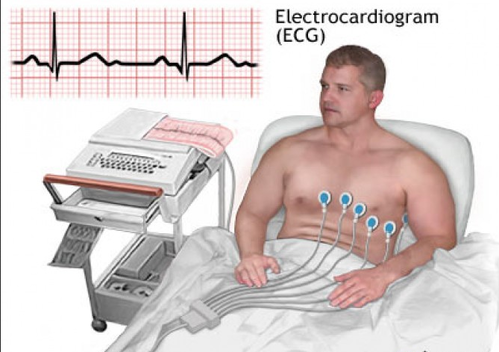

Step Five: Patient is connected on electrocardiogram

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Links Cited: https://5.imimg.com/data5/KB/JI/GLADMIN-10702249/electro-cardio-gram-ecg-test-500×500.png

Pain Points:

- Patient may find the small, adhesive electrodes irritating to his or her skin

Step Six: Apply sedative

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Links Cited: https://i.ytimg.com/vi/X-EWklbJMzY/hqdefault.jpg

Pain Points:

- Patient may wake up a few times

- Anesthesiologist has the communicate with patient not to move, keeping him calm and applying more sedative and anesthesia

- Anesthesiologist is concerned about overdosing patients (especially, if they are elderly)

Step Seven: Place sterile towel over groin area

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Links Cited: https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=images&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjdgOuL-pDcAhWUn4MKHSz0BCMQjRx6BAgBEAU&url=https://www.wikihow.com/Irrigate-a-Foley-Catheter&psig=AOvVaw3NrCWB-y5HKyBYmznVicSZ&ust=1531189097862654

Pain Points:

- Patient is sensitive about his or her privacy

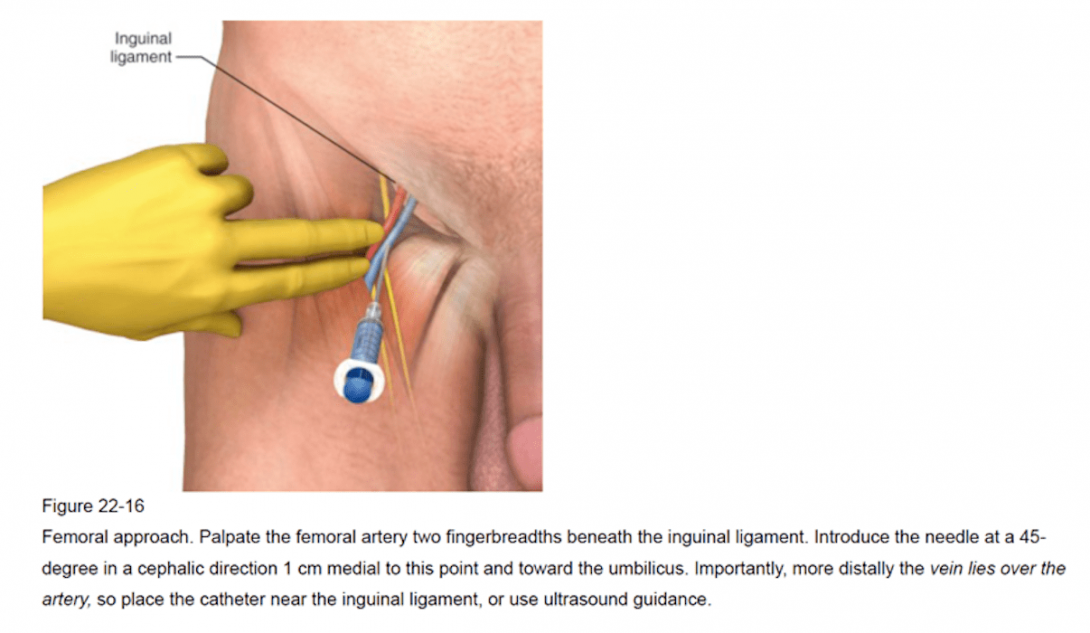

Step Eight: Clean and apply local anesthetic to groin area

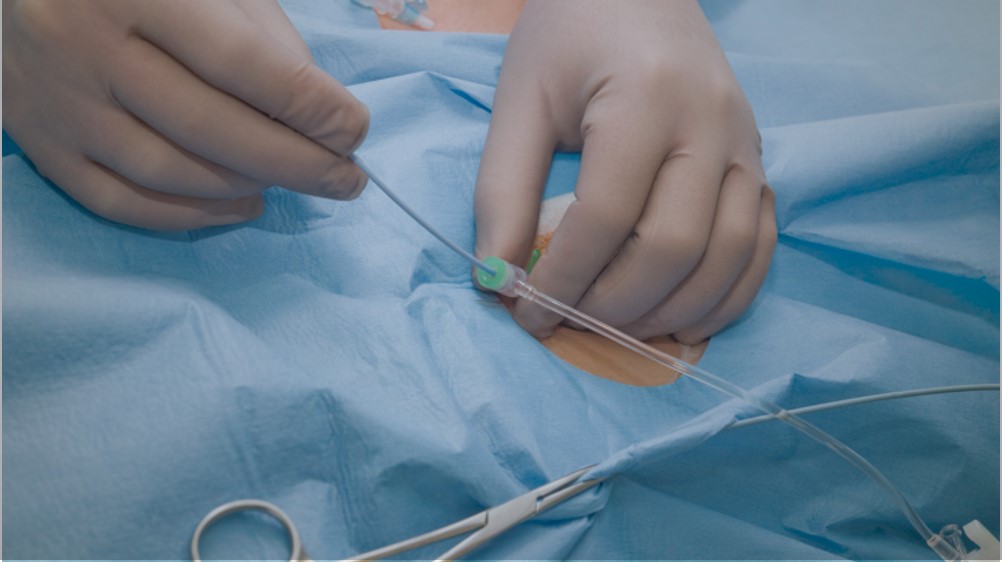

Image:

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Pain Points:

- Doctor may have difficulty locating correct vein with needle

- Doctor needs to drain some blood out of vein to facilitate path of PA catheter

- Patient’s blood may gush quickly or uncontrollably

- Patient may feel burning or stinging when numbing medicine is applied

- Patient may feel pain from the pressure of the needle puncturing the vein

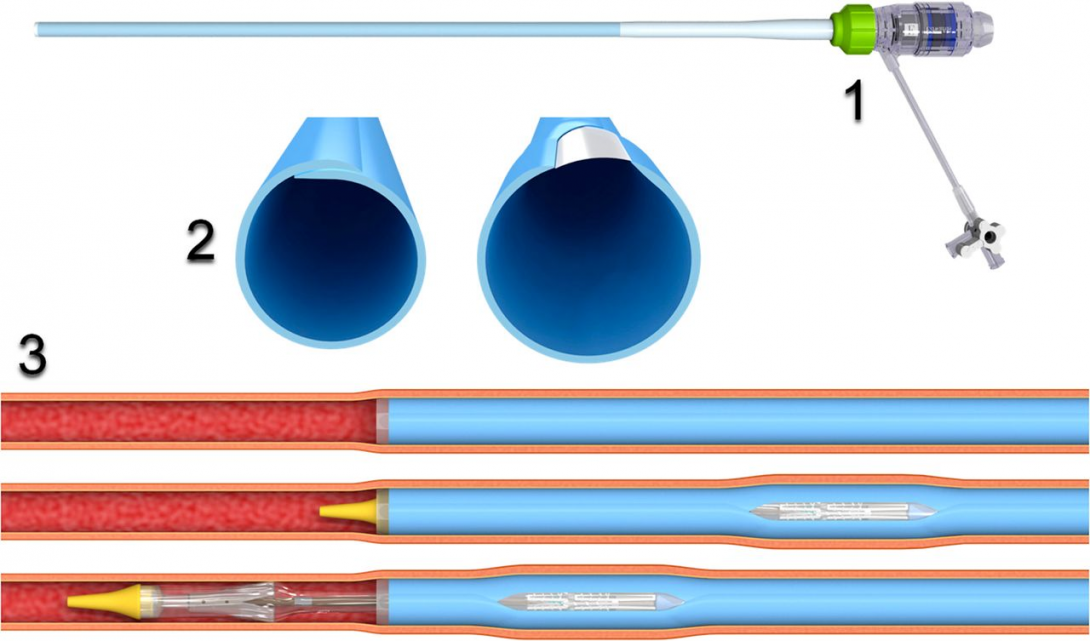

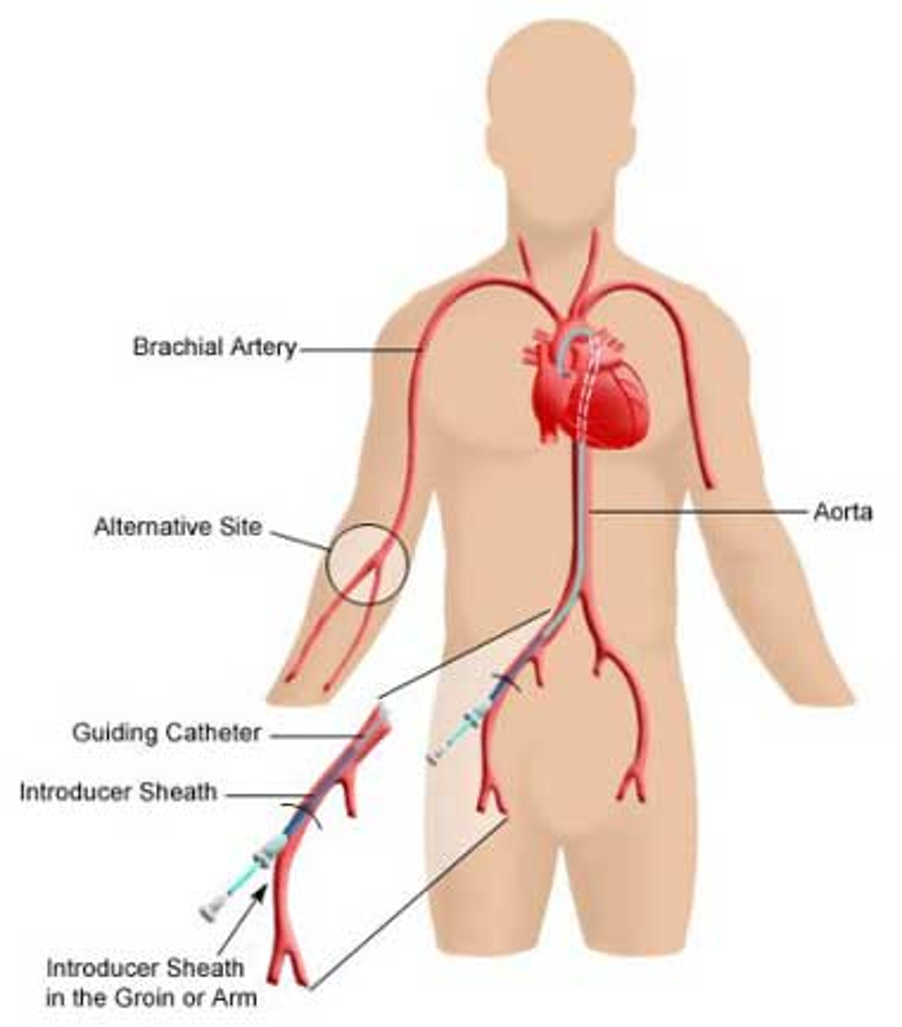

Step Nine: Doctor places an introducer sheath in vein

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Links Cited:

Pain Points:

- Patient’s blood may gush quickly or uncontrollably

Step Ten: Doctor inserts Pulmonary Artery (PA) Catheter through introducer sheath

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Links Cited:

Pain Points:

- It may take the doctor some time to get the PA Catheter all the way through the vein into the correct vessel

- Doctor is concerned about puncturing vessels

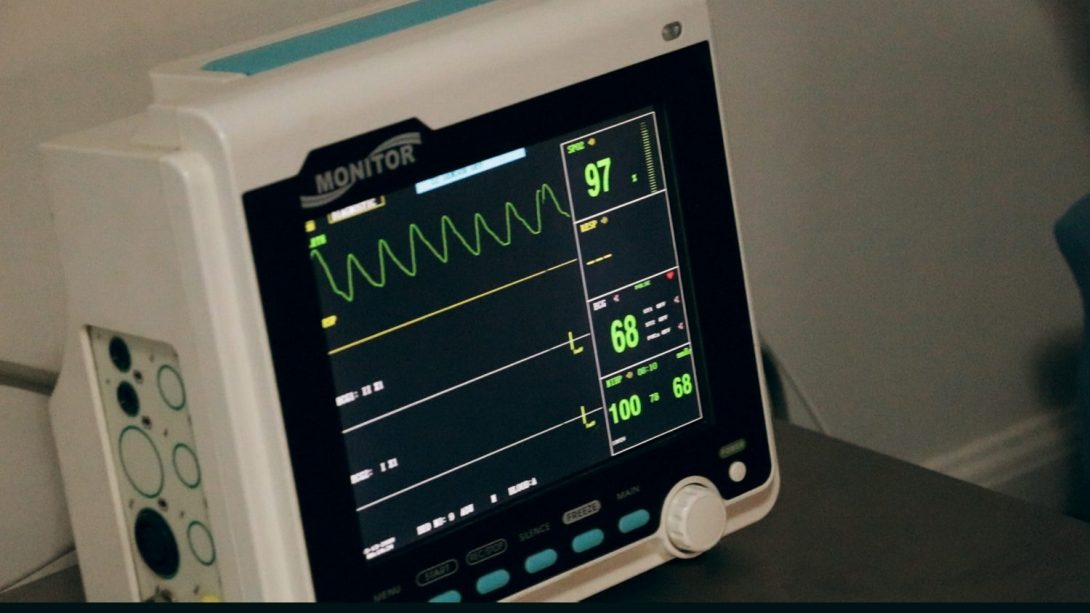

Step Eleven: Measure heart rates

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Links Cited: http://safa.ps/uploads//images/b39e45184e8f2112eca99445211bcfb7.jpg

Pain Points:

- Doctor has to get necessary info about heart pressures (increasing or decreasing),which could take an hour or more to do, depending on the severity of the patient’s condition

Step Twelve: All done! Remove catheter and introducer sheath

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Links Cited: https://cdn1.iconfinder.com/data/icons/social-messaging-ui-color-shapes/128/thumbs-up-circle-blue-512.png

Pain Points:

- Doctor does not want to puncture the veins while extracting the catheters

Divinefavor’s Week 3 Blog

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

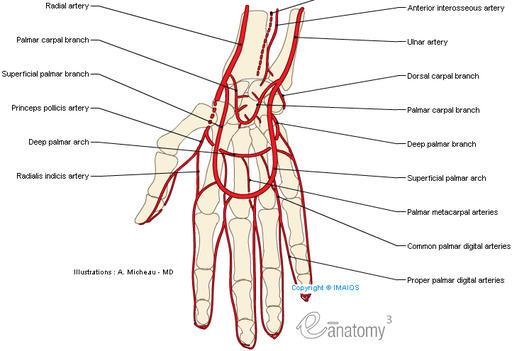

This week, my team and I listened to a nursing fellow in the Catheterization Lab of Cardiology department in order to identify what is truly needed to improve the work flow there. Based on her feedback, we have developed this needs statement:

First Iteration:

“Making it quicker and easier for an assistant nurse to set up a mid-axial transducer to line up to the patient’s mid-bracial.”

Second Iteration:

“Develop a device that will increase a nursing fellow’s efficiency in setting up a mid-axial transducer to be parallel relative to the patient’s mid-bracial.”

Reason for change (from 1 to 2): I changed “an assistant nurse” to a “nursing fellow” to better describe who we are aiming to help. Secondly, I changed “line up” to “parallel relative to” because it is less ambiguous. Also, I changed “quicker and easier” to “increase . . . efficiency” because it describes the purpose of our project more concisely and accurately. Finally, I included “Develop a device” because it better reveals what we intend to do to help improve the nurse’s workflow.

Third Iteration:

“Add an additional component to the mid-axial transducer that will assist the fellow in setting up a mid-axial transducer to be level relative the patient’s mid-bracial in a time-efficient manner.”

Reason for change (from 2 to 3): I realized that the primary complaint of the nurse we interviewed was that the doctor needs the mid-bracial transducer to be set up immediately and even before he starts a procedure, hence the addition of the phrase “time-efficient”. Furthermore, failure to do so may lead to the delay of the procedure, as well as criticism from the doctor. Also, I changed the phrase “parallel relative to” to “level” because “level” more accurately describes the goal of the nurse’s job in the scenario she described to us. Finally, I altered “develop a device” to “add an additional component” because it simplifies our project to something that is less costly but effective.

Clinical Immersion Program (Week 4 Blog)

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

Needs statement

Optimizing accessibility of left radial artery in order to decrease doctors’ radiation intake, expedite patient recovery, and reduce possible dorsal weakening for doctors’ convenience.

Link: http://www.easynotecards.com/uploads/114/21/19a62d5a_15cf0d334be__8000_00000495.jpg

Design specifications

Based on the feedback of one of the doctors of the Cardiology faculty, the design should be made of a “soft” material (ex. Foam), for patients feel the effects of “hard material” during surgical procedures and are therefore agitated and complain afterwards. Furthermore, that soft material must be “spray able” by the nurses so it can be sterile for the next use.

Link: http://www.hospitalpatientbed.com/photo/pl15262068-waterproof_cloth_adult_hospital_bed_foam_mattress_for_bedridden_patients.jpg

Design criteria

According to the feedback from some nurses and doctors in the Cardiology faculty, they (the nurses and doctors of the Cardiology faculty) are looking for a “simple” design that is “cheap” and “easy” to set up. In other words, the design must be intuitive to set up for the patient and be easily detachable from and attachable to the operating table. However, the design also should not be “too expensive” to make or purchase. In addition, it must be comfortable for the patient, as well as be adjustable to the patient’s unique size. Finally, the design should provide optimized accessibility of the left radial artery for the doctor.

Figure 1: Photos of varying forearms sizes.

Link: https://us.toluna.com/dpolls_images/2015/05/24/a3262f34-18fc-4837-9aa0-ac69f13e4bfd_x300.jpg

Link: https://i.dailymail.co.uk/i/pix/2015/09/24/00/2C9A67E300000578-3246720-Sarah_s_elbows_were_lifted_with_PDO_threads_which_form_a_mesh_un-a-70_1443051884038.jpg

Link: https://media.istockphoto.com/photos/man-arm-with-blood-veins-on-white-background-picture-id623928092?k=6&m=623928092&s=612×612&w=0&h=5p3YdwCs7pQ4_mkDrtXDwc2Db_v69i6EbCPNwJcuVMA=

Divinefavor’s Blog Week 5

Divinefavor Osinloye Blog

This past week at clinics has been very productive, yet restful. Personally, I have developed more confidence in asking questions- even to the point that I was able to obtain consent to take more detailed pictures of the catheterization lab with a patient’s arm in it!

Moreover, our team was also able to conduct more interviews with a number of doctors in tge Cardiology department. Moreover, we gained helpful feedback and tips to take into consideration for our project on the left radial access for right-sided catheter procedures.

That being said, our team had a lot of different ideas on what could be done to solve the problem of left radial access for right-sided catheter procedures. The most challenging thing about it was deciding on which idea would be the most effective for our project. Despite this, we were able to finally reach a consensus on which project idea to embark on for our project. Furthermore, we even went to Michaels and Home Depot to look for materials we could work with to model our design; the rest of the modeling will be completed with SolidWorks.

Overall, I am very grateful for the outcome of the Clinical Immersion Program. Not only has it been a greater active learning experience for me than in class room settings, but it has also personally helped me to grow in maturity and social interaction. Kudos to Dr. Wissner and all the other doctors and nurses for welcoming us into their workplaces. Kudos to our supervisors of the Clinical Immersion Program, and a special kudos to Aseel and Erik for not only being the best partners one could ask for, but for also being best buddies with me throughout this program.

Rown Parola

Rown Parola Blog

Rown Parola Blog

Week 1: Good and Bad Design

Rown Parola Blog

During the first week we observed several instances of good and bad design. I actively tried to broaden the scope of design I was considering beyond the prosthesis that are most often associated with orthopedic surgery.

I started by being on the lookout for work-arounds, barriers, re-purposed objects, and instances of user “torture”. The best example I saw occurred multiple times and with two different orthopods in different clinics when they wanted to explain a procedure, pathology, or anatomy to a patient. They would draw what they were talking about on the paper overlaying the exam bed. This method was very effective in explaining things to patients and allowed the patient to take the drawing home with them too. One example Dr. Gonzalez drew of thumb ulnar collateral ligament repair is pictured in the heading of this post.

Good design observed this week

- Thumb UCL replacement surgery

- Proximity of physical therapy to the orthopedic department

- Gameready braces that pump hot or cold water into the brace and can also do compressions

Bad design observed this week

- Call center scheduling inappropriate patients for specialists

- Each physician had their own method for keeping track of their calendar which was backed up to the eMR

- The computers in every exam room were never used

One last area that might benefit from innovation was encountered during a follow up with a patient who had some winging of his scapula as his muscles would get fatigued. The physician suggested that the patient take a friend to their PT appointment as a workout buddy. The workout buddy would be able to see when the scapula would wing and inform the patient. It seems that a mirror or video system might be an easier solution for this problem.

Week 2: Clinical Inefficiencies

Rown Parola Blog

This week we spent time in the clinic identifying clinical inefficiencies. The physicians were aware of a few they were quick to bring to our attention, but we also wanted to follow patients through their experience to see if we might be able to identify inefficiencies they may not have thought about.

Chiefly, the physicians were concerned with the repeated steps, and chances for error that may occur due to multiple people interviewing patients. We noted that when a patient first arrives at the clinic an MA will bring the patient back to the room and complete an intake form which collects information about allergies, chief complaints, and a pain score among other items.

Sounds great, right? The problem is that this information is not made available to the medical care team. Even if it were entered into the eMR, the information is not filed in clinical notes due to the way the software is set up. That’s not even the whole problem though. Since the MAs are so busy they don’t enter the intake forms until the end of the day because filling out the forms requires too much time navigating through different screens.

Over the next week we are going to work to address this issue by reaching out to Cerner to see if the software might be able to streamline the process and file these notes in the correct location.

In following patients through their appointments we were able to identify a few more inefficiencies. One illustrative example relates to the boy pictured above who came to clinic to have his cast removed after a fracture. His visit went as follows:

1:45 Patient called back for cast removal, because cast room is full patient placed in “x-ray room”