Terrence Lin

Student Participant

BME Senior Undergraduate - Neural Engineering Concentration

Department of Anesthesiology

Pronouns: He/Him/His

Email:

Week 1: Good Design vs. Bad Design

Fish out of Water

Before the Clinical Immersion Program (CIP), my experience in medicine consisted of my nurse aide training and working as a research assistant in a psychiatric research center when I was exploring pre-med as a career track. Now exploring careers in medicine more aligned with engineering, the anesthesiology group was thrusted into a new environment of the operating room (OR). Within the first week, we experienced a wide array of surgeries such as a jaw restructuring procedure, an open-chest surgery, and an organ transplant. To be honest, it was quite a jolt to transition from summer break to witnessing patients at their most vulnerable during surgery. A fish out of water feeling so to speak.

Keeping the “fly on the wall” analogy taught to us to ease our transition, our group took this week to prioritize observing and understanding the workflow of the OR without interfering with the doctors and nurses involved. Being able to witness the OR environment so intimately gave a renewed respect of the work healthcare workers do for their patients. Not only that, but during slower portions of the operations, circulating nurses and the Anesthesiologist were kind enough to reach out to us and answer the many questions we had about the procedure and equipment they used.

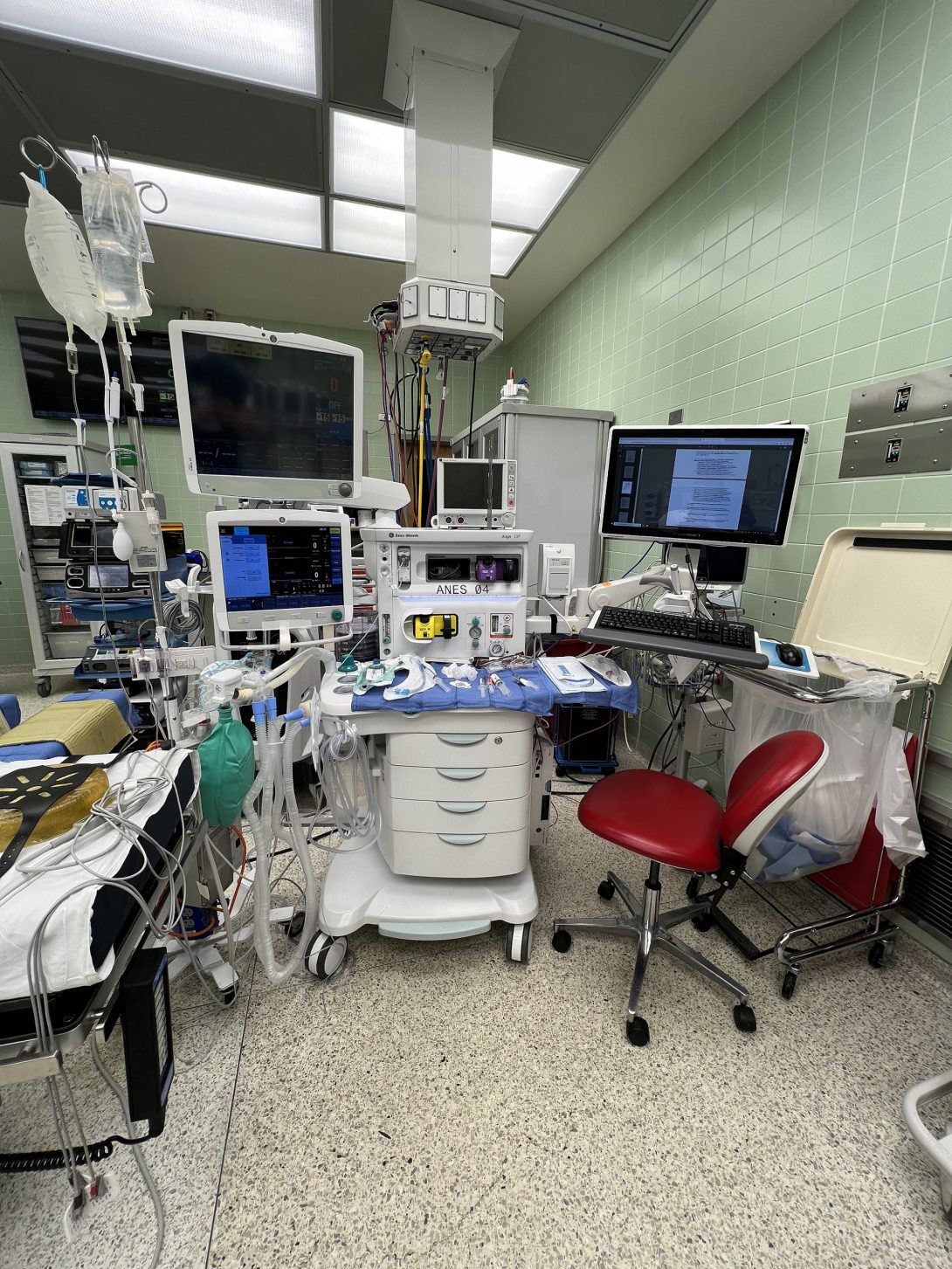

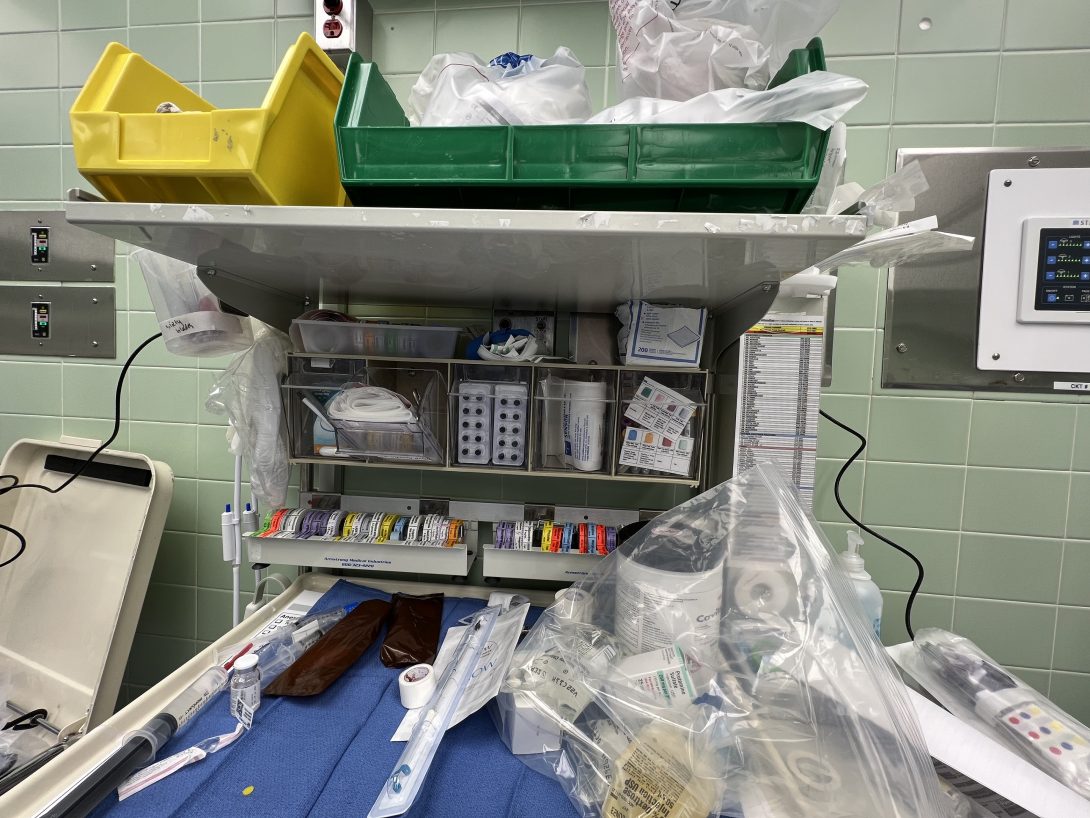

Good Design: When speaking with one of the nurses, a feature of the equipment we noted was how modular everything was. You will almost always find tools and modules on lockable wheels, such as the patient’s bed, vitals screens, the Anesthesiologist’s carts, and IV bag hangers. This in turn allows ORs to be transformed to accommodate the specific surgery they will perform.

Bad Design: An unfortunate consequence of modularity is tidiness. While it is by no means messy, the OR will have certain situations where different equipment will get in the way of each other, making navigating the OR and certain stages of surgery cumbersome. A notable example I noticed was a wire of an electrical surgical tool. When connected to the wall outlet, it ran across the floor, giving a potential trip hazard. While this was mitigated with an adhesive wire cover and coiling the wire around the stand for the surgical tool, this solution in turn didn’t give the surgeon enough wire slack to maneuver around his patient and operate properly. This was a pain point that was continually addressed throughout surgery to accommodate for both the equipment going over the wire and the surgeon.

Week 2: Story Board

Breathing for the Patient

Now that we’re getting more comfortable with the operating room, our teams were tasked to create a story board of an event that took place in the environment that we observed. For anesthesiology, they oversee many different processes that help regulate the patient’s health throughout surgery, such as regulating the patient’s temperature with blankets heated with ventilated air and adjusting the patient’s blood pressure by injecting medication through the IV drip.

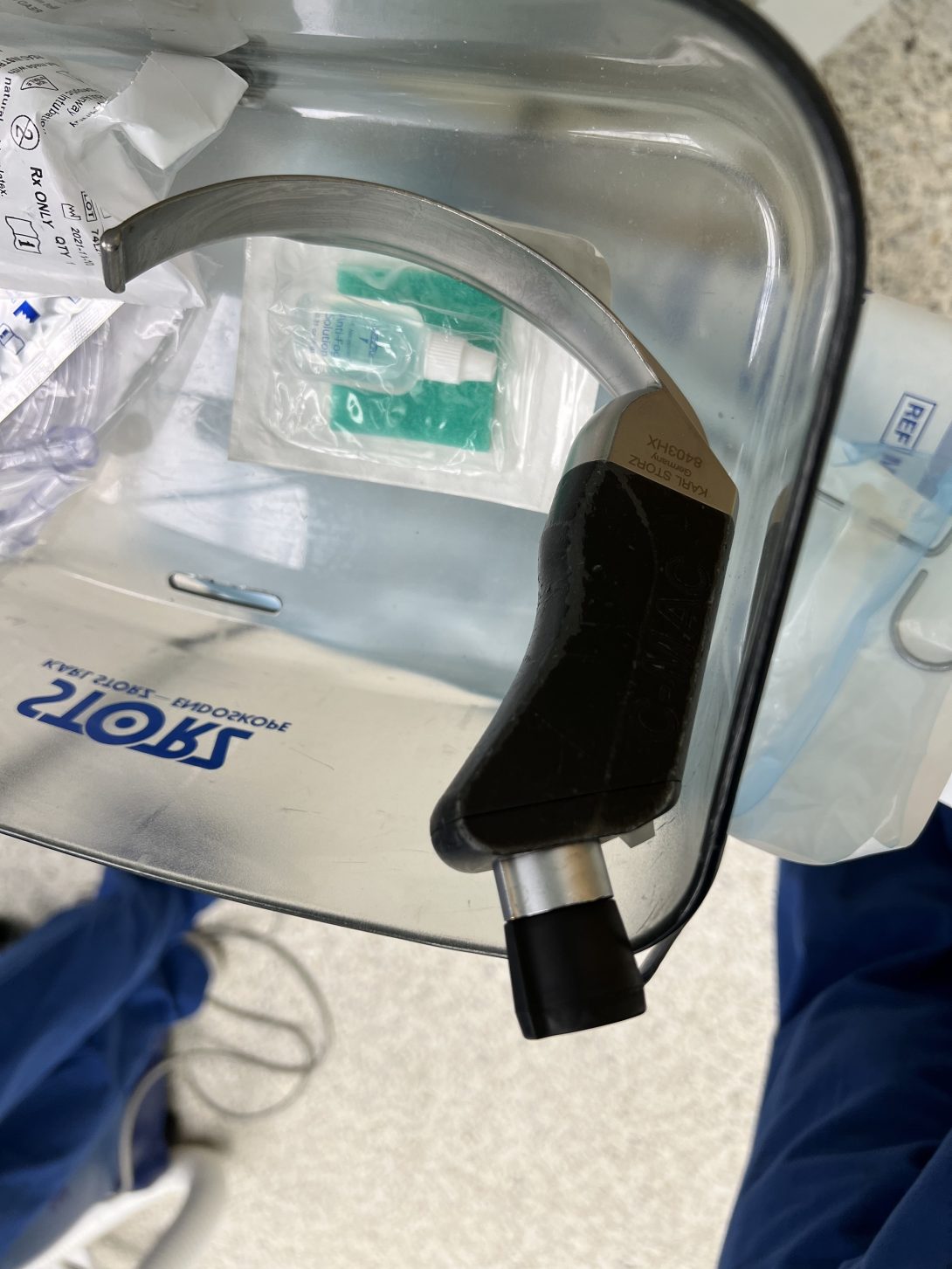

The one consistent process the team found represents the anesthesiology workflow well was intubation. For a brief summary of intubation, anesthesiologists intubate patients in order to secure a direct airflow to the patient’s airway so they can safely deliver oxygen and anesthetics to the lungs. This is done by using a MAC blade, a curved metal instrument, to clear the airway and guide the tube through the airway and to the trachea.

While this is a tried-and-true procedure for major surgeries, it does not come without its failure points. Most patients are intubated while induced by paralytics and general anesthesia, and while it achieves the desired effects of making the patient comfortable throughout the surgery, it also means they cannot breathe for themselves until intubated. Because of this fact, failure to intubate can cause severe hypoxemia and cardiac arrest. To help aide in the intubation process, either a tracheal tube introducer (“bougie”) or an endotracheal tube with stylet is used to guide what would normally be a relatively flexible tube.

Week 2 pt. 2

In Brian Driver’s clinical trial, he aimed to test whether a bougie or a stylet was more effective in producing a successful intubation. This was done by having an observer collect data from the randomized surgery. The results of the 1106 randomized participants in this clinical trial was that a bougie or a stylet was not significantly significant to producing a successful intubation over the other. While avoiding a failed intubation is important to the anesthesiologist, avoiding these situations are done by predetermining what kind of intubation is right for the patient and evaluating the risk factors. In extreme cases, anesthesiologists have ways to reverse the anesthesia effect if deemed necessary.

Referenced research article: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8655668/

Week 3: Needs Statement Iterations

We became actors

Just as a quick aside, in our mentor’s, Dr. Nishioka, efforts to let us experience as much of his responsibilities as possible, we got to become extras in a film shoot promoting the UI Health’s new and upcoming hospital building. While it was not related to this week’s CIP goals, it was absolutely the highlight of my week as it was not an experience we’d expected to have.

So… How can we help?

The focus of this week is on needs statements, statements important for scoping projects as it is a solution-oriented summary of a project. It includes a group of people, a problem that is affecting them, and the end result that the project aims to achieve. This is wrapped up into an acronym taught to us in our Monday weekly meetings, POO, representing population, opportunity, and outcome respectively. This is the structure we use to shape our needs statements.

Iteration 1: Healthcare providers in long-term care and surgical environments may deal with IV catheter failure and need preventative measures to decease IV catheter failures rates.

- Population: Healthcare providers in long-term care and surgical environments

- Opportunity: IV catheter failure

- Outcome: Decrease IV catheter failure rates

With this first iteration, my goal was to get familiar with the POO structure and look to improve from there. I used IV catheter failures as an anesthesiology related issue to practice this structure. While this needs statement is a good baseline, its biggest flaws come from the scope. The population is too broad, making the range of different interactions with IV catheters too large to resolve meaningfully. The opportunity can also be focused on a specific IV failure if deemed necessary, such as infiltration.

That is not to say that this is not a serious problem in the medical field. According to Robert Helm’s review article, “more than 300 million peripheral IV catheters are sold each year in the US” but has an “overall failure rate of 35% to 50%”. IV catheter failures, such as infiltration, dislodgement, and infections, can cause longer hospital stays and increased hospital costs of “up to $56,000 of additional costs” per case.

Referenced review article: Accepted but Unacceptable: Peripheral IV Catheter Failure (uic.edu)

Week 3 pt. 2

Iteration 2: Anesthesiologists working in surgical settings running longer than four hours may run into organizational issues when handling their medications and need a method of making their workflow more efficient.

- Population: Anesthesiologist in surgical settings running longer than four hours

- Opportunity: Organizational issues when handling their medications

- Outcome: Method of making their workflow more efficient

After internalizing the concept of creating a needs statement more throughout the week, I wanted to choose an opportunity that anesthesiologists are more intimate with. One pain point that our group heard of was how handling medication, IV bags, and blood bags was described as “juggling everything”. This is further exacerbated when the procedure runs long and continuous periodic use of drugs becomes complex.

In reviewing, this needs statement is overall has scoping issues on the population and outcome. For the population, procedures running longer than four hours does not always necessitate the use of a wide variety of drugs. For the outcome, “a method” is too broad of a solution to be actionable.

Week 3 pt. 3

Iteration 3: Anesthesiologists working in surgical settings on patients with complicated medical histories may run into organizational issues handling medication, IV bags, and blood bags during procedures and need a systemic approach to making their workflow more efficient.

- Population: Anesthesiologists in surgery working on patients with a complicated medical history

- Opportunity: Organizational issues handling medication, IV bags, and blood bags

- Outcome: a systemic approach to making their workflow more efficient

The goal of iteration three was to refine the scoping of iteration two. Speaking with Dr. Nishioka shed light on how exactly the anesthesiologist’s workflow like. He showed us that a patient’s medical and surgical history is often the factor that complicates the material anesthesiologists need for that procedure. He also shed light that there is no “one way” to do the anesthesiologist work and the organization largely depends on each physician. It is these two facts that refined the population and outcome statements of this iteration of the needs statement

Overall, iteration three is an improvement on scope. While an argument can be made that the scope is still too broad, I believe that the large scope of this needs statement opens the floor to innovative solutions that answers to an organizational problem of a wide array of materials.

Week 4: Patents and IPs

Devices and Solutions

This week, we have focused on patents and intellectual properties (IPs) and how they are used to answer need statements. In my case, my new needs statement I’ve looked into is “When the ventilator fails mid-surgery, anesthesiologists need a reliable way to manually ventilate the patient”.

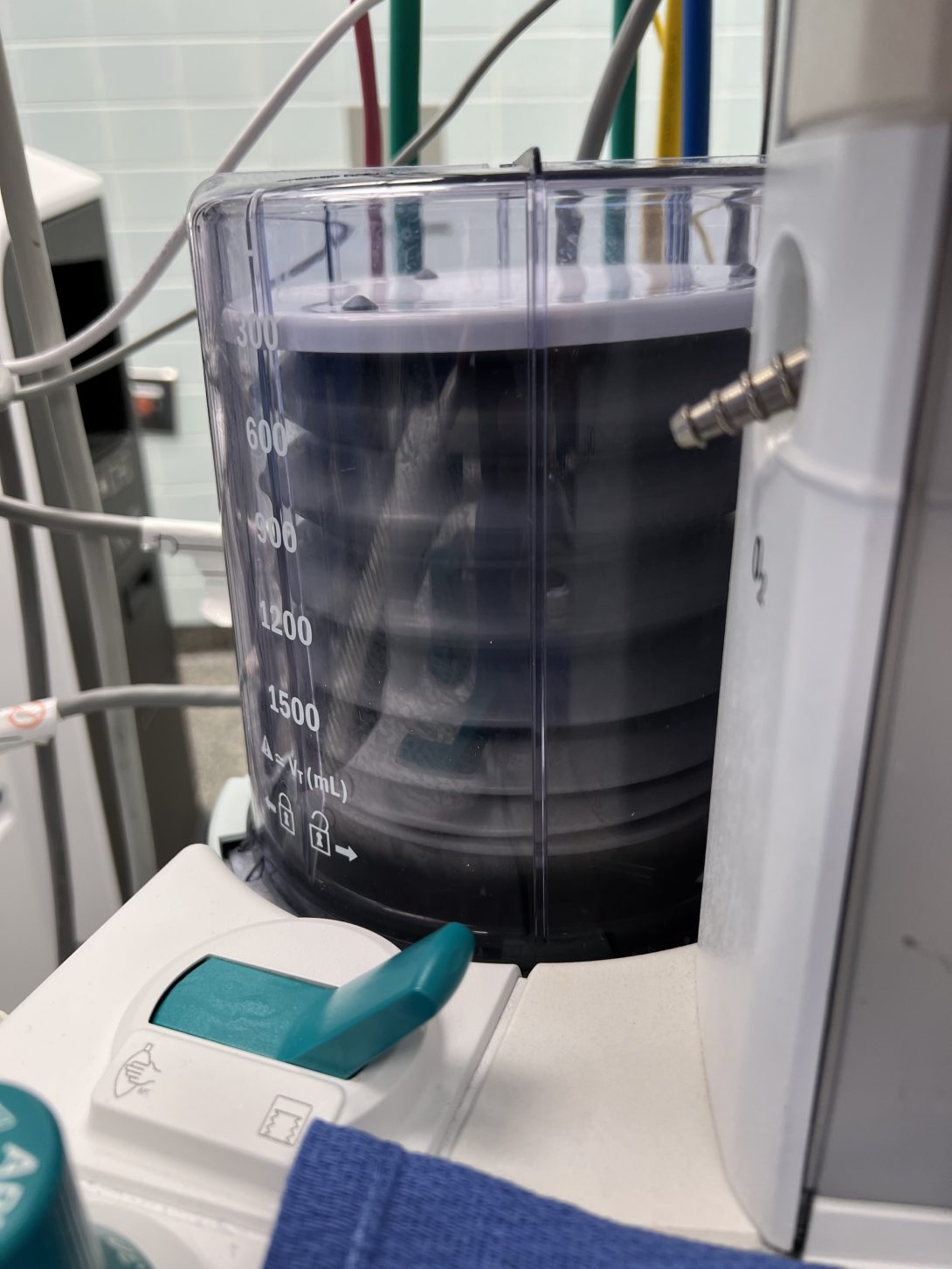

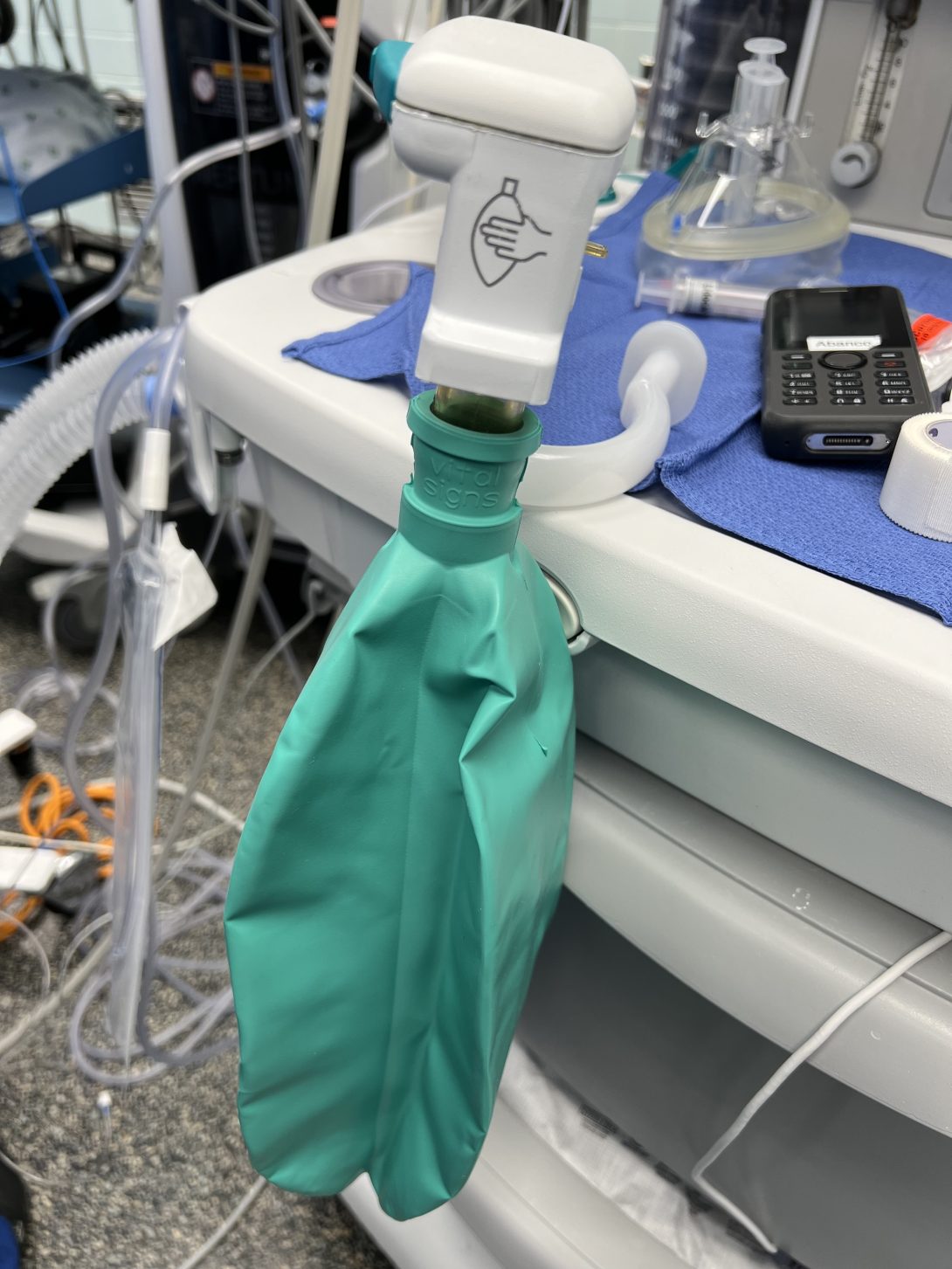

With that needs statement, I looked into the anesthesia machine that are used in UI Health’s anesthesiologists, the Aisys CS2. From the European patent number EP1795222B1 by General Electric Co., the anesthesia ventilator system is a ventilation system that provides an automatic breathing system for the patient via an inhalation conduit to supply gas and an exhalation conduit to receive exhaled gases. The claim I wanted to focus on was the manual ventilation system that can be set to replace the inhalation conduit via a switching valve assembly.

Week 4 pt. 2

Based on my personal observations and the anecdotes of the anesthesia physicians we interviewed, the Aisys CS2 works reliably for the amount of uses it goes through and rarely does it fail to the point where intervention was needed. To be frank, the manual ventilation is usually used out of preference during certain situations. Based on previous MAUDE reports and Dr. Nishioka’s previous experiences, the errors the Aisys CS2 that causes it to malfunction are overheating and condensation from exhalation reaching the circuitry of the device.

Aisys CS2 Patent: EP0904794A2 – Automatic bellows refill – Google Patents

Week 5: Market

Intubations of Difficult Airways

Now that the final weeks of CIP are upon us, we’re closing in on the final project proposal we plan to present for our final presentation. Intubation is a part of every anesthesiologist’s workflow, and difficult airways was a common issue brought up in workflow processes to improve. So, for our final needs statement, we decided to go with “Medical professionals in emergent settings who intubate patients in an emergent setting experience difficulty visualizing the airway due to contamination and need to increase first-time intubation success rate”. We wanted to focus on emergent settings because they don’t have any control in the patients they treat and the settings they give medical care in when treating difficult airways.

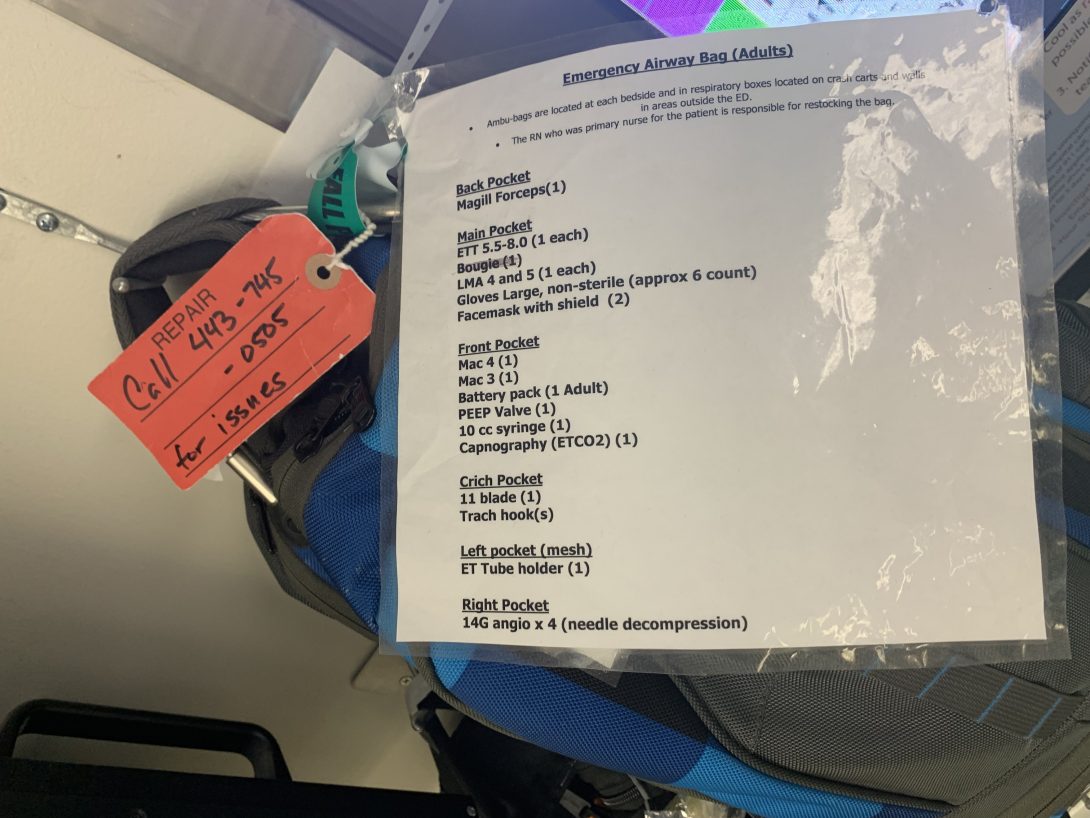

In the ED, we learned that compactness, reliability, and versatility of the tools they use are of paramount importance, especially in difficult intubations. All three are important because the emergency airway bags they carry only has a limited amount of space, so a value proposition comes up to take up that precious space. One of the tools they use are suctions in order to deal with aspiration from potential blood or stomach contents they deal with during intubation.

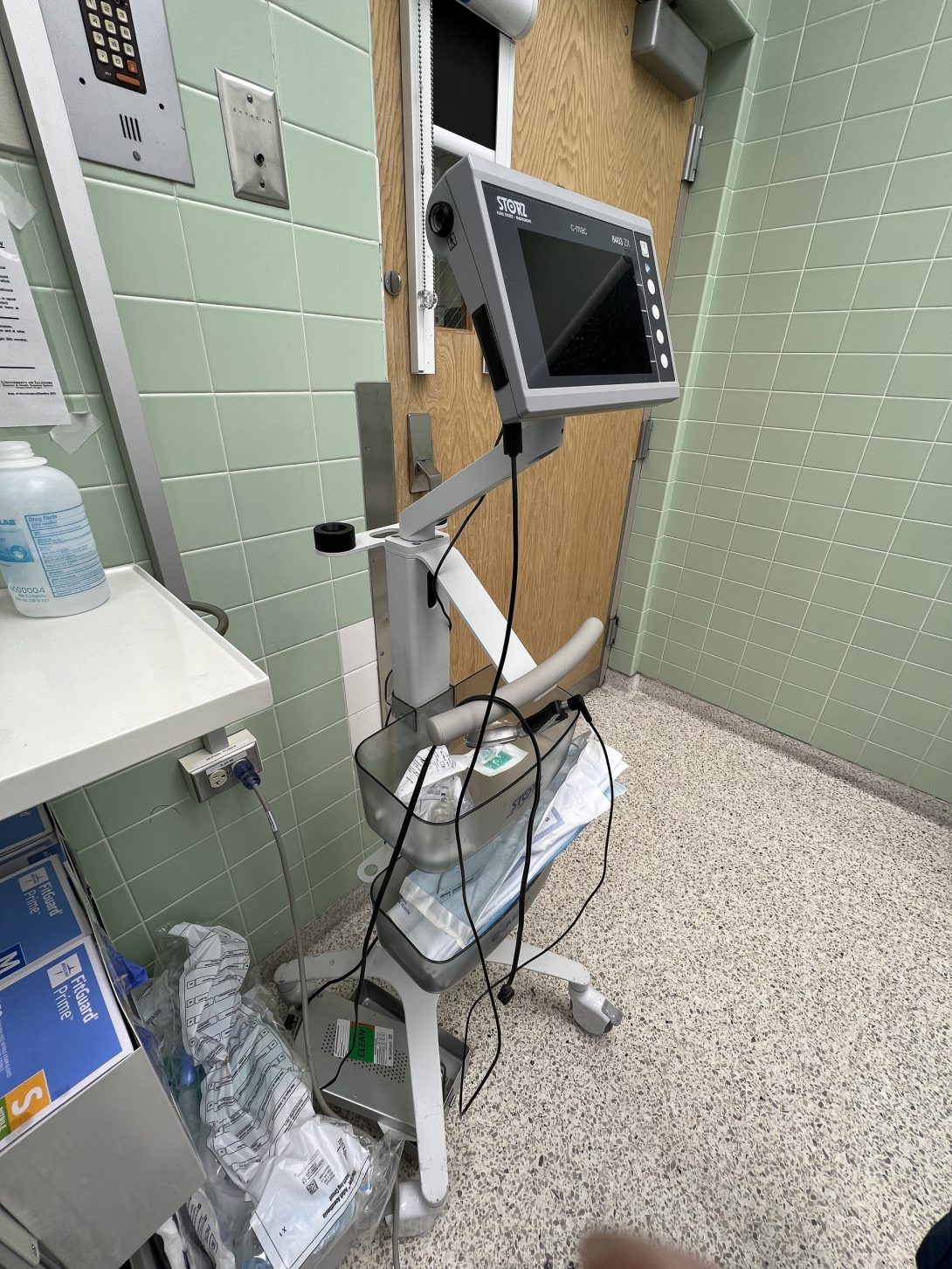

The tool we looked at as a group was video laryngoscopes, an important tool for intubations as it visualizes the airway and leads the endotracheal tube to the entrance of the trachea for ventilation. The blades for the video laryngoscopes are single use to maintain sterility in an efficient manner. Given that about 413,000 intubations happen yearly and the typical single use laryngoscope blade costs $18, the total addressable market would be about $7.4 million.

Week 6: We're Finished!

A Look Back

It’s hard to believe that these past six weeks have flown by. It honestly felt like yesterday when I was struggling to find a place to stand in the OR. Now, I have used my experience in both the clinic and lectures to create a project proposal that a BME senior design team will take up in the upcoming school semester.

Advice

If I were to give advice to a newcoming CIP student, I would say to keep an open mind and be vigilant. A lot of the immersion aspect of CIP will be self-motivated and you won’t always have a clear idea of what exactly you should be taking away. So be a sponge and take in whatever experience you can and don’t be afraid to step in and ask questions! Even a question as simple as “where can I stand to observe?” helps with getting to know the medical providers you’ll be getting acquainted with throughout your time in CIP. I wish you luck!