Vivian Nguyen

Student Participant

IMED Scholar, MS2

Department of Neurosurgery

Week 1: The Week I Decide to Become a Neurosurgeon Heading link

What an incredible first week of the clinical immersion program (CIP) in neurosurgery! After spending much of my first year of medical school working my way through various organ systems and discerning whether I could see myself in certain specialties, I had not considered that neurosurgery would make it onto my differential (albeit we haven’t covered our neurology block yet). Perhaps the title of this post is a tad facetious after just one week, but perhaps this is the summer that I get a preview of the field and give neurosurgery a chance. This week, my team and I met our clinical mentor for the summer, Dr. Ankit Mehta, as well as a neurosurgery fellow and some residents. We spent some time observing in the neuro ICU, the operating room, and the neuro clinic. Each environment had its own unique challenges and intrigue, but common to all was that everyone was so welcoming and willing to answer questions. In the weeks leading up to the start of the program, I was filled with excited butterflies and nervous anticipation for what my summer in neurosurgery would be like. I have to say that this first week did not disappoint. From craniotomies and spinal fusions to reading imaging and assessing pre- and post-operative patients, the pace and dynamics that I witnessed in neurosurgery this week was truly inspiring.

Attention to the Awesome

In my observations this week, I felt like everything was so impressive. I saw so much design that I perceived as good, and after all, how could the OR function in such an awesome capacity if the design wasn’t great? However, I also recognize that much of this week was for becoming accustomed to the neurosurgery department and the operating room, so perhaps it was challenging to observe with a critical eye when I was focused on just taking everything in. Nonetheless, one of the many “good” designs that I noticed this week was the design of the neurosurgical suction cannula used during a craniotomy procedure. The aspect of the design that struck me as particularly elegant was the opening designed into the cannula that allowed the surgeon to place their thumb and control the pressure within the suction device with one hand. While I could see some user issues arising, perhaps with a surgeon’s hand slipping from the suction device and allowing too much pressure while the brain is exposed, the design itself was simple, intuitive, and appeared ergonomic. Other good designs that caught my eye were the cranial drill that stopped drilling when the surgeon had gone far enough and the add-on caddy that was adhered to the surgical field to hold the various surgical instruments.

Room for Improvement

In this first week of CIP, I found it challenging to compartmentalize my role as a medical student interested in the clinical, surgical, and medical aspects of my observations vs. my intended role as an IMED student collecting observational data about the environment, the processes, and the user needs within neurosurgery. In the moments when I was able to make that distinction, I was able to take note of a few areas of improvement. On the other end (almost quite literally) of the suction cannula where I noted good design, there was a moment in which the flow of a spinal fusion surgery was disrupted when one of the surgeons asked the scrub nurse to check the “suction tube which has become anemic.” I watched as the nurse checked the suction tube connection ensuring that the suction itself was not the issue. The nurse then moved on to examine the tube itself which revealed that it had become occluded. The nurse took forceps and attempted to clear the tubing as the surgeon’s hand remained outstretched, awaiting the return of his ability to control bleeding and visibility within the surgical field. The stall in surgery signaled to me an opportunity for improvement. Could the nurse have just swapped out the tube? How often does an occluded suction tube occur? These are certainly questions that I will continue exploring in the coming weeks. Other areas of improvement that I noticed were the lack of control a surgeon has over an intra-operative ultrasound due to the plastic sterile covering and the gloves of the surgeon, spatial cord management, and designing the OR for smaller/shorter individuals.

Week 2: The Week I Notice More Than Meets the Eye Heading link

Throughout week 2, our team continued to gather a breadth of information. While the work of the surgeons is obviously a focal point of the department of neurosurgery, I began to take note this week of all the processes and teams that may appear at the fringe but actually contribute significantly to the overall function of the department, the success of surgeries, and the quality of care for patients. In particular, we were able to gather insight from rounding with the neurology team in the neurosurgical ICU (NSICU) and observing other stakeholders such as NSICU nurses and medical device representatives in addition to making observations from the surgeons’ perspective. At any given moment, whether it be in the NSICU or in the operating room, teams of neurologists, nurses, and pharmacists or anesthesiologists, imaging technicians, and medical device representatives are running their own course and playing their own role in the hospital ecosystem.

With such a bustling environment, there are bound to be challenges with smooth patient hand-offs between nurse shifts, communication amongst the various teams, and sometimes something as seemingly simple as having enough room or chairs that fit in meeting rooms. As I gain a better understanding of the neurosurgical environment, I realize that there is more than meets the eye below the surface of the surgical component; there are unspoken norms between nurses, mutual understanding about communication between provider teams, extra steps and workarounds that have become what appear to be norms. In the weeks to come, I look forward to continuing to peel away layers and uncovering insightful ways that innovation can play a role in the neurosurgery department.

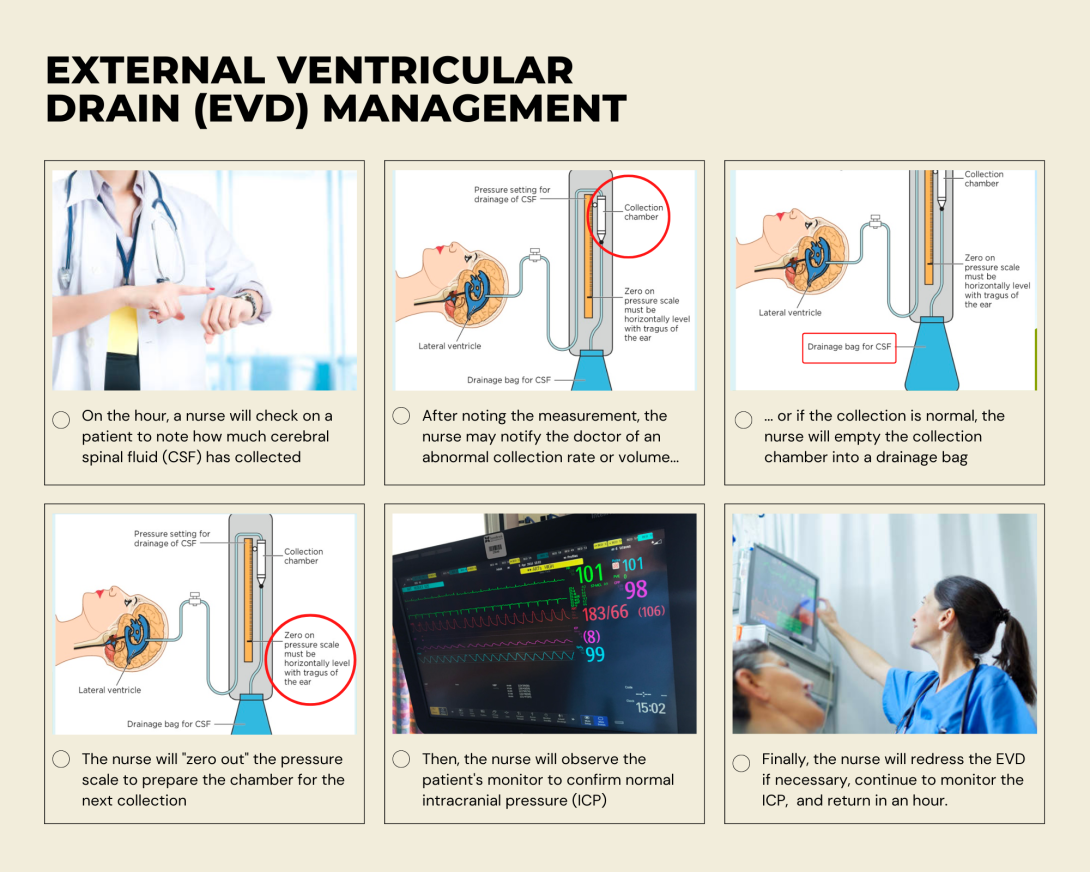

While shadowing a nurse this week, I had the opportunity to observe the care of a patient with an external ventricular drain (EVD). From what I gathered in my observation as well as speaking with the nurse, I created a basic External Ventricular Drain (EVD) Management storyboard. A few points in particular that I was interested in:

- Any kink or occlusion of the drain tubing can cause erratic intracranial pressure (ICP) readings and thus set off false alarms

- Zero-ing out of the pressure scale relative to the patient’s ear is subjective as the nurses simply step back and eye it

- Increased monitoring required for more complex cases (thick or clotting CSF), which can place a care burden on nursing staff who are already checking the levels every hour

- Monitoring and discretion whether to notify the physician can be dependent on nurse experience

- Nurses must remember to open and close clamps appropriately with rare but fatal consequences (EVD drains CSF completely)

- In rare cases, there is potential for EVDs to be pulled out

When turning to the literature, I identified a review paper entitled, “External ventricular drain management in subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” While there are numerous indications for patients requiring EVDs and although the paper focused on the conditions of subarachnoid hemorrhage, I found that the overall emphasis of the review paper was relevant because it highlighted that the methods and strategies revolving EVD management and monitoring lack optimization and standardized implementation. The review article revealed key findings in studies that pointed to the need for evidence-based care for patients with EVDs. For example, during the meta-analysis, researchers found that “EVD-related infections occurred in 12% [of patients] who underwent continuous CSF drainage and 2% [in patients] who underwent intermittent CSF drainage. The random effect meta-analysis confirmed that the risk of infection was significantly higher for patients undergoing continuous CSF drainage.” Other findings were related to the process of weaning patients off of the EVDs, which are only intended for temporary use, either gradually or rapidly. Nonetheless, the review article noted that studies conducted multi-center surveys and found that “there is still a discrepancy between evidence and common practice.” In some ways, this review article validated some of the questions I had about the aspects of subjectivity that I observed during EVD care and also presented evidence for ways EVD management can be optimized for patient outcomes.

Week 3: The Week I Imagined an OR for People Like Me Heading link

Imagine being trained to use surgical tools that you can’t quite wrap your hands around or performing a procedure that requires the use of force that you can’t quite generate from one hand. Does that make you less fit for your line of work? Some find workarounds or adaptations, but imagine having your career being centered around the care of others’ health –yet the tradeoff is that your work comes at a risk to your own health. Who heals the healers? These are some of the questions I had this week as our team spent time in the OR. I was particularly struck by the experience of one of the female neurosurgeons who was of smaller stature and surgical glove size relative to all of the other neurosurgeons that we had shadowed.

Two situations in particular caught my attention. The first was the surgeon having to stand on a stool for the entirety of the operation. This added to the need to navigate the OR with the stool in tow, especially when surgeons needed to switch positions or when everyone needed to clear away from the patient during intra-operative imaging. I was also curious about the neurosurgeon’s access to the “cut” and “coag” foot pedals that I had seen used in previous surgeries to control the electrosurgical instruments. If the surgeon was standing on a stool, how could she use the pedals freely? The second situation arose when the surgeons had arrived at the point in the spinal surgery where she had to adjust a large self-retaining retractor to increase exposure and access of the lumbar spine. I watched as the surgeon put down her bovie and picked up two osteotomes which she placed in the two finger loops of the retractor. Taking both hands, she pulled the two handles of the osteotomes together in order to generate sufficient leverage to effectively retract the patient’s mass. Seeing the surgeon struggle, as this is typically done with one hand, the recently trained male scrub nurse stepped in to assist with retracing but also did so with some visible difficulty. Finally needing better visualization of the surgical field, the senior male surgeon with larger hands and who was better able to apply greater force stepped in to retract before the procedure went on.

Based on these observations, I became curious about the application of ergonomics and human factors in the design of ORs and the instrumentation used within its walls. What would it look like to design an OR or surgical instrumentation that was optimized for the female surgeon we shadowed, for a shorter individual, for a smaller-handed individual… perhaps for someone like me? My curiosity led me to some preliminary literature research, and I created the following needs statements synthesizing the direct observations and my findings.

Female neurosurgeons performing spinal surgery face challenges with using one hand to effectively utilize retractors and need tools that account for ergonomics and human factors to increase comfort and command of instrumentation use.

- P – female neurosurgeons

- O – using one hand to effectively utilize retractors

- O – increase comfort and command of instrumentation use

Neurosurgeons performing spinal surgery face challenges with using one hand to effectively utilize instrumentation like retractors and need tools that account for ergonomics and human factors to reduce the strain necessary to apply the tools as desired.

- P – neurosurgeons performing spinal surgery

- O – having to use one hand to effectively use surgical instrumentation

- O – reduce the strain necessary to apply the tools as desired

Surgeons with smaller hands and less grip strength face challenges in using surgical instrumentation lacking universal ergonomics and require tools that account for human factors to increase comfort and command of instrumentation use while reducing physical strain and the need for treatment due to maladaptation.

- P – surgeons with smaller hands and less grip strength

- O – surgical instrumentation lacking universal ergonomics

- O – apply human factors design to reduce physical symptoms and the need for treatment due to strain or maladaptation

As I progressed through these iterations of my need statement, I was challenged by striking a balance between what would be an appropriate scope for the particular need statement and taking into account the broader scale of the problem space. In terms of the population, my reflections and my research suggested that the scope of “female surgeon” was somewhat too narrow. This reminded me of the classic example of OXO kitchen tools, designed for the “extreme user” with severe arthritis and yet benefitted all who use their kitchen products today. The problem I observed isn’t just about designing for women or surgeons of smaller stature in surgery, it’s a matter of making tools more ergonomic for everyone. While my opportunity space began with the retractor specifically, I recognize that other processes involving instrumentation could benefit from more direct observation and universal design such as the process of using inserters to place screws and rods. Finally, with the development of my outcomes, I included both a measurement of improvement as well as a measurement of reduction in order to capture the immediate and longitudinal effects on the need.

Week 4: The Week I Stand in Ambiguity Heading link

In week 4 of CIP, our team continued to synthesize the didactic material from our weekly workshops, time in the OR, and research into the academic literature as well as in the space of patents and manufacturer/user device experiences. It was a busy week of brain tumor removals and cervical fusions in the OR, which for us meant more observation and insight into one of our areas of interest: surgical head clamps. The space around surgical head clamps appears to be unchanged for the past few decades despite reports of adverse events –though most are designated as user error or improper application of the device. To me these events, which are likely underreported in cases where no significant adverse outcomes for the patient were experienced, begs the question: if the head clamps are considered well-designed and have become the gold standard, why are there so many cases of user error? Sure, these are complicated instruments that are being used, but I also consider how “good design” can account for how intuitive a device is as measured by the ease of use. Perhaps there is more room for improvement in these surgical head clamps than surgeons who are trained and use these instruments daily are aware of.

On the other hand, I couldn’t quite shake the lens of ergonomics and human factors in the OR, and I found myself attuned to observations around patient positioning, surgical team orientation and movement, and experiences with instrumentation by various users. The general sentiment I’ve found in the literature and from stakeholder perspectives suggests that there is in fact some underlying need in the space of OR ergonomics. Yet, the domain is so broad and the needs so multifactorial that it has been a challenge defining such a problem. My mind has been swarming this week with ideas and considerations and different angles to progress this project space. How do I balance scoping the problem with the scale with which it exists? Does the scarcity of rigorous literature and research of the problem point to the existence of the problem or the lack thereof? How much of this problem is due to the instrumentation or design, and how much is due to the system or culture within surgery? This week has been filled with plenty of variables and unknowns and unanswered questions, but I suppose navigating the ambiguity and sitting in the discomfort of not having well-defined answers is all part of the process to clarity.

I recognize that innovation and human-centered design is always a work in progress, so there has to be a starting point, even if it’s imperfect. In my current headspace, my target user still revolves around surgeons with smaller hands, the specific instrument I observed as an opportunity was a retractor, and the outcome is to create a more ergonomic and universally designed way to achieve the same goal of retraction during spinal surgery. So as I continue to trust the process, a starting point this week revolves around this iteration of my need statement:

- Surgeons with smaller hands and less grip strength face challenges with using one hand to effectively utilize retractors and require a more ergonomic approach to retraction during spinal surgery in order to reduce the physical strain required to apply the tools as desired.

In my perusal of “ergonomic retractors,” I came across the patent “US10874385B2” which was recently granted in 2020. In this patent, three embodiments of design for ergonomic retractors are described. Interestingly, the patent describes ergonomics from the angle of both the procedure itself (i.e. designing an ergonomic retractor for a specific procedure and tissue anatomy) as well as for the surgeon use (i.e. making it easy to maneuver and use the retractors in both adult and pediatric patients). The patent approaches ergonomic design for the procedure as a way to increase anatomic fit of the retractor to the area of operation and to decrease risk of damage to tissue or relevant structures. It also takes into consideration the ergonomics of the device for surgeon usability by describing a mechanism for maintaining retraction. Coming across this patent opened the door to the question: how do we define “ergonomics” in the context of surgical instruments?

Based on my understanding of the approach and claims of this patent, I think this design is a step in the right direction in terms of incorporating ergonomic design into surgical retractors. However, I have some reservations about whether or not such a design would address the opportunity that our team has identified –namely, whether or not this design could be used universally across hand sizes and grip strengths. I think it is possible for the design to confer greater ergonomics relative to current standard surgical retractors, but it may not quite address the needs of our target population. Furthermore, our observations have led us to believe that retraction is commonly done single-handedly, and my understanding suggests that the mechanisms described in the embodiments of this patent may not account for that nuanced design criteria observed in the OR.

Week 5: The Week I Find Some Clarity and Compromise Heading link

Clarity and compromise were the name of the game this week as we continued to seek a balance between desirability, feasibility, and viability. It became clear to me that while the problem space of surgical ergonomics –especially as it pertains to smaller-handed and smaller-statured individuals– was an important exploration and would be a worthwhile endeavor, the scoping of such a multifaceted project into something meaningful would require more time and research than I have during the remainder of CIP. With that clarity came the compromise we’ve made as a team to marry our primary interests of surgical head clamps and OR ergonomics. Although it would be more of a tangential aspect to our identified need, ergonomics and human factors are ubiquitous and applicable to the use of surgical head clamps as well. As such, our working need statement moving forward reflects a more implicit need for ergonomics in the outcome:

Surgeons preparing for cranial and cervical spine procedures face challenges in positioning and stabilizing the head and require an ergonomic and secure way to reduce patient complications and increase ease of surgeon usability.

As we move forward in this space of surgical head clamps and also apply the lens of improving ergonomics, we wanted to explore the current market space. We were able to access some data via the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which accounted for 240,000 cranial and cervical spine cases performed annually in the US. With an estimated cost of $50 per patient, this suggested an approximately 12 million dollar total addressable market. At first glance, the longevity of the reusable head clamps and the trusted functionality of the clamps points to a relatively small direct market space. However, there are some limitations to our estimates. The data we were able to access through the AHRQ database was only up to date as of 2007, suggesting the market may have expanded over the years as passing generations age or as technology improves the ability to diagnose and treat patients. Furthermore, the nature of surgical head clamps and their reuse poses challenges to identifying an accurate cost per patient per use which could also affect the current estimates.

Additionally, our research of head clamps and surgical ergonomics suggest that there are also indirect costs to the use of these devices. Implicitly, and where more of the ergonomic factors come into play, the indirect costs of a device that is functional but may not be the most ergonomic could be found in the costs of treating complications that arise. The cost of complications –slippage, lacerations, subsequent infections– can compound and present as increased length of stay in the hospital or the use of additional resources to treat the complications in addition to the surgery itself. Our exploration into surgical ergonomics suggests that user errors can add an additional mental stress to surgeons and poor human factors design of instrumentation can cause physical symptoms of pain and the need for rehabilitation over time. While much more longitudinal of a cost, the cost to surgeons is also an angle we felt was worthwhile to factor into our value proposition. Given these discussion points, it is our assumption that the true addressable market for the space of surgical head clamps may be greater than our current market estimate.

Week 6: The Week I Embrace Closure Heading link

It’s amazing how quickly the program came to a close this summer. It’s been quite the journey from that first day of neurosurgery clinical immersion to presenting our final proposals. Over the past 6 weeks, there were moments of enlightenment and some of frustration, but ultimately, our team crafted a proposal that we could be proud of.

In week 1, I “decided I wanted to be a neurosurgeon,” and the notion behind that post has not changed much. Looking back now, I learned so much, both explicitly and implicitly, during my time in the neurosurgery department this summer. From a clinical perspective, I continued to be fascinated by the medical cases, the surgical approaches, and the interactions that existed among the surgeons and their OR teams or with their patients in the clinic. I’m grateful for this opportunity to preview neurosurgery and by extension surgery in general as it pertained to my clinical interests. However, I also learned from an innovator’s perspective about how challenges in neurosurgery (and arguably all of the specialties) were so often multifactorial. I found that in the surgical field, there is perhaps a particularly strong cultural component to the perception of pain points. “It’s just how I was trained… the residents will adapt as they progress through their training…” These were the sentiments our team noticed both directly and indirectly during our work to identify needs. I think the success of innovation in this space is so strongly correlated with stakeholder-buy in and therefore must account for the culture in the field as well. At the same time, surgeons are also some of the best assets to innovating in this space because of their meticulous attention and knowledge of their work. Their feedback and guidance is essential for identifying true needs and promoting widespread adoption of an innovative idea in the long run.

In week 3 of the program, I “imagined an OR for people like me,” and it reminded me of how much value I draw from engaging in the design/innovation process. Going through the program this summer, I learned once again to lean into the ups and downs that can accompany this challenging work. This process is an avenue for creativity that in my experience can be so easily lost in the fast-pace of a medical school education. It allows for taking a step back and noticing the bigger picture. To do this work well, it demands an engagement with both the art and science of medicine –embracing empathy to understand and anticipate users’ needs while also applying the rigor of research.

The program taught me that developing the skills I need to be a good innovator also helps me to grow into the best physician I can be.

Through weeks 4 and 5, I drifted in a state of ambiguity and found my way to a breakthrough into clarity, compromising where necessary along the way. These weeks in particular taught me lessons about myself and how I navigate the space between seeking to understand and seeking to be understood. It taught me lessons about how to work in interdisciplinary teams and how that collaboration brings a greater sum than its parts.

As we conclude week 6, my advice to future CIP participants would be this:

- This program is what you make of it. You get out what you put in, and what you put in can certainly become something so meaningful –whether that’s the project you develop or the skills and lessons you learn or even just the friendships you form.

- For medical students: you can certainly get so much out of this time to explore a clinical department, but don’t overlook the opportunity to put down your “medical student hat” and take the time to see the clinical world through the eyes of your engineering teammates. Their questions will surprise you and their perspectives will challenge you. Embrace their curiosity, and you’ll have so much fun along the way!

- Trust the process.

Finally, a round of thank-you’s for everyone who made this experience possible. To Drs. Kotche, Browne, and Felder who created a wonderful space for us to explore, imagine, and learn. To our clinical advisor, Dr. Mehta who gave us the freedom to find our way around the OR and around our needs-finding with just the right amount of guidance. To the clinician, nursing, and provider teams in the Department of Neurosurgery for allowing us to shadow and question and occupy precious space in their ORs. To the other IMED and BME students who created a fun and collaborative cohort. And last but certainly not least, to Team Neurosurgery (Dionna Bidny, Nora Qatanani, and Sam Winters) who joined me on this journey this summer –it’s been a ride!