Sitara Rao

Student Participant

Week 1 Blog: Good and Bad Designs in Anesthesia Heading link

This week, my Clinical Immersion team shadowed anesthesiologists mainly in the operating room. We had the chance to observe a vast variety of surgical cases spanning so many different areas of medicine. In doing so, we started to get a feel for how anesthesiologists work to adapt to the differing needs of surgical teams, different types of operations, and the differing medical conditions of their patients. While much of our week was spent generally learning about the OR and the anesthesiologists’ role there, we also started to take notice of how they interact with devices such as infusion pumps and monitors, how they craft workarounds to broken or ineffective devices, and their mental workflows as they make clinical decisions. Also interesting about this week was that Friday was the first day with new interns starting and resident classes turning over. We got to see how this change in roles affected staffing, communication, and productivity in the department.

Below are some designs that stood out to me during week 1:

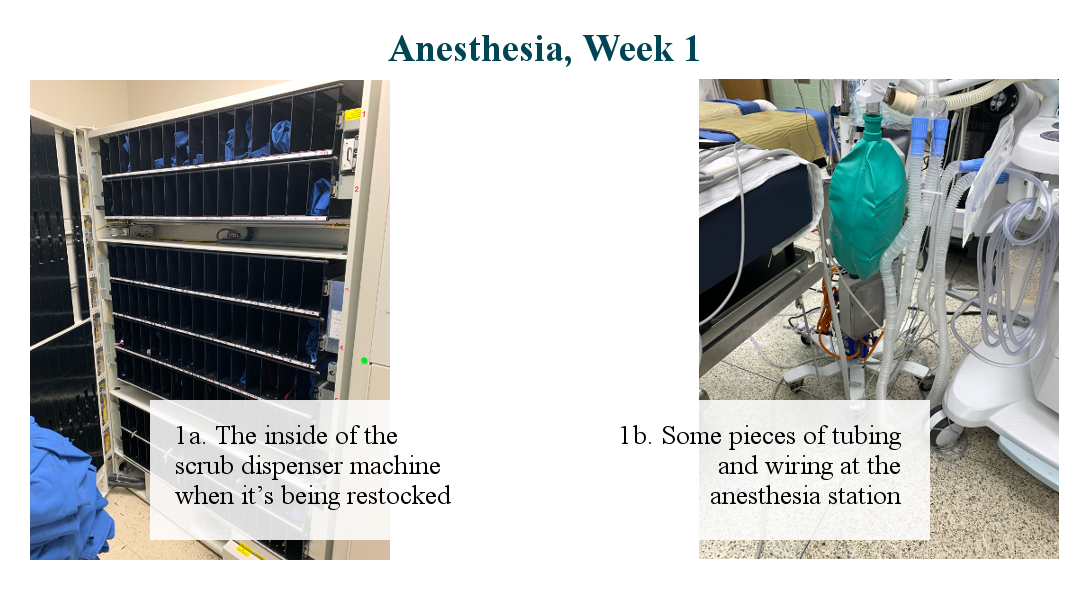

Good Design: Scrub Machine

When entering the OR suites, everyone must be wearing a pair of hospital-cleaned OR scrubs. In order to acquire a pair, those entering the OR need have scrub credits loaded onto their ID card. They swipe their card in the scrub machine, which prompts them to pick a default scrub size if they haven’t already, then locates a correctly sized pair of scrubs if it is in the machine and reports its location to the user. The user then opens the door indicated by the screen, and only their scrubs are visible. If the size requested is not available, the user can cancel the request or pick another size.

When the user is done in the OR and is ready to have their scrubs cleaned, they must return them in the scrub receptacle machine in order to have their credits reloaded so they can request their next pair of clean scrubs.

I like this design because I think the credit system holds people accountable for the scrubs they take and prevents waste from people misplacing or not returning scrubs. In my short experience with using the machine, it is reliable– I have never requested a size and received a different size (though my preferred size has been unavailable on some days, but that is a stocking/supply issue rather than one with the actual device). The instructions are also quite clear and intuitive. There is a sign to swipe your ID, and once you do that, each prompt is short and easy to follow. The whole process from swipe to retrieving scrubs takes about 30 seconds. The machine also keeps the scrubs very organized and clean because the user can only access their pair of scrubs.

Bad Design: Tubing. EVERYWHERE.

Photo 1b. was taken in between surgical cases. There is usually a lot more clutter during an operation. All this tubing and wiring comes from IVs, fluid bags, breathing tubes, monitoring equipment, and other necessary attachment points between the patient and anesthesiology equipment. Since no two cases are the same, the attachments that are required can vary quite a lot based on complexity of the case; the more complex the case, the more connection points, tubing, and clutter at the anesthesia station. We were told that the level of clutter this produces is mostly dependent on how organizationally minded the anesthesiologist is. When disorganized, these attachments can cause tangles, confusion as to what is what, tripping, and even dropping things while rearranging/accessing parts. These may seem like minor annoyances, but even distractions and nuisances in the OR can have consequences.

This lack of structure seemed to me in stark contrast to the organization of the rest of the OR. Generally speaking, OR equipment has its place: sterilized surgical tools are laid out in trays, cabinets are clear and labeled with their contents, and usually it is quick for a trained eye to find and get to things. With anesthesia equipment, that is not always the case when there are tubes and cords in the way of what the anesthesiologist is trying to get to. I watched people juggle fluid bags trying to access another one, accidentally jostle a tube connected to the patient when trying to give a drug bolus, and heard unprompted complaints from several disgruntled anesthesiologists about how frustrated they were with the tubing and wiring mess in front of them.

Week 2 Blog: The Shortest Clinic Week Ever Heading link

This week, I was only in clinic for one day due to a long weekend and travel plans. Due to these constraints, I was determined to make Wednesday a very productive day and this was indeed the case! In the morning we sat in on a Morbidity and Mortality (M&M) meeting in the anesthesia department. We listened to the department discuss difficult patient cases in order to promote dialogue and collaborative thinking about how things might have been done differently. The session heavily emphasized resident interaction and education, with attendings encouraging residents to answer questions and engage with the cases. We noted that both of the two cases discussed in the session were about airway management and intubation/extubation.

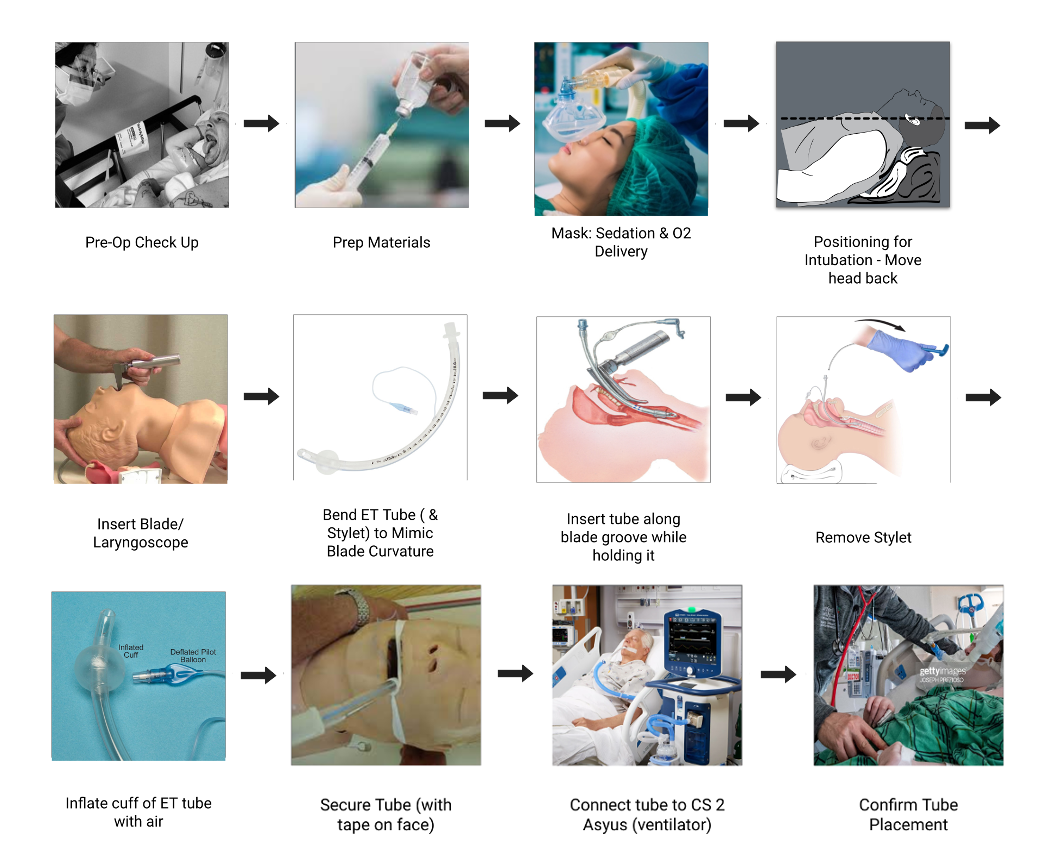

The passionate discussion around airway management and its many difficulties led our team to wonder if the process of intubation would be a good space for needs identification and storyboarding. Throughout the rest of the day, my team attempted to observe as many intubations as possible to get a better idea of the steps of the procedure, the tools used, difficulties encountered, and how the process is taught to students and residents. We came up with a skeleton storyboard and asked questions to refine it. Throughout the rest of the week, I was out of clinic but received updates from my teammates about refining our perceived steps of the procedure as well as notes about the tools needed and pain points encountered. We used these observations to produce the storyboard above.

During our research of airway management, our clinical mentor Dr. Nishioka sent us the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ difficult airway management guidelines, which synthesizes the current literature and evidence-based findings in order to create an algorithm for airway management. The guidelines provide a flowchart outlining the steps to take in case difficulties are encountered at various points during the intubation or extubation process. As is the case with many emergency protocols, the guidelines detail an algorithm that helps clinicians make quick decisions on next steps to take during what can be a very stressful and time-sensitive situation.

In observing intubations, our team noted that several were performed using video laryngoscopy. When we asked why this was done, the anesthesiologist told us that, when a complicated airway is noted during pre-op assessment, video laryngoscopy is a helpful tool to guide endotracheal tube passage down the airway and avoid difficulty and complications. I found a 2015 study by Mort and Braffett comparing traditional direct laryngoscopy to video laryngoscopy in patients with high-risk airways that measured adverse outcomes and number of intubation attempts as endpoints.

To identify “high-risk” airway patients, the researchers used variables including sex, age, BMI, facial edema, and administration of neuromuscular blockers in their pre-intubation assessment. The study found that first attempts at intubation were more successful in the video laryngoscopy group (91.5% vs 67.7%, p = 0.0001). Video laryngoscopy also significantly decreased the incidence of adverse events such as hypoxemia, esophageal intubation, bradycardia, and cardiac arrest. The researchers state that, compared to traditional direct laryngoscopy, the superior view of the airway offered by the video laryngoscope allows for easier insertion of the endotracheal tube, which in turn results in fewer adverse outcomes and fewer situations requiring emergency resuscitation. They conclude that video laryngoscopy is an approach that can markedly improve outcomes when intubating a patient with a high-risk airway.

Jeffrey L. Apfelbaum, Carin A. Hagberg, Richard T. Connis, Basem B. Abdelmalak, Madhulika Agarkar, Richard P. Dutton, John E. Fiadjoe, Robert Greif, P. Allan Klock, David Mercier, Sheila N. Myatra, Ellen P. O’Sullivan, William H. Rosenblatt, Massimiliano Sorbello, Avery Tung; 2022 American Society of Anesthesiologists Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology 2022; 136:31–81 doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000004002

Thomas C. Mort, Barbara H. Braffett; Conventional Versus Video Laryngoscopy for Tracheal Tube Exchange. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2015; 121(2):440-8 doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000825

Week 3 Blog: Needs Statements Heading link

This week, I had the opportunity to sit in on a root cause analysis (RCA) meeting. Though the details pertaining to a specific RCA are confidential, the general idea of this process is to delve deeper into a significant event in order to identify the systems-level failures that occurred and discuss changes that can be implemented to prevent future occurrences. I was intrigued by this process and decided to focus on developing my needs statement around errors and error reporting.

When a significant event happens in the hospital, it can be brought to the administration’s attention either by an anonymous report or by escalation to superiors. When I asked our mentor, Dr. Nishioka, to look at the patient event reporting tool used by clinicians at UI Health, we had some trouble locating it in the user portal. This led me to my first iteration of my needs statement: Clinicians who commit near-misses or medical errors without clinical implications on the job need an easily accessible way to anonymously report their errors. I emphasized near-misses and less consequential errors in this needs statement because more serious events are more likely to require escalation through non-anonymous routes. Near misses are more likely to go unreported and potentially leave room for serious errors to occur.

- Population: Clinicians who seek to report near-errors and less consequential errors

- Opportunity: Anonymous patient event reporting tool is difficult to find, introducing barriers to error reporting

- Outcome: An easy way to report small errors and near-errors

In looking closer at this needs statement, I realized that clinicians have less incentive to facilitate error reporting than hospital administration. The data from the patient event reporting tool is used by administration to track compliance with standards such as those set by the Joint Commission, a prominent healthcare accreditation organization. Some serious events are known as ‘sentinel events.’ According to the Joint Commission, a sentinel event is “a patient safety event that results in death, permanent harm, or severe temporary harm.” In order to improve the quality of hospital operations and comply with such standards, UI Health must rely on reports to identify errors that indicate opportunity for process improvements, even when these errors do not result in serious harm. This led me to my second iteration of a needs statement:

Hospital Administrations who experience difficulty with quality improvement need a way to get consistent event reports on near misses or medical errors without clinical implications.

- Population: Hospital administration

- Opportunity: More data needed for systems-level quality improvement

- Outcome: An accessible tool that enables clinicians to easily report near misses or medical errors that do not result in serious harm

Sometimes, sentinel events that are noted by hospital administration do not trigger a root cause analysis meeting. Other times, there can be a root cause analysis meeting about a serious undesirable event that does not qualify as a sentinel event. The team that investigates such incidents and decides whether or not an RCA is triggered is the hospital’s risk management team. When a significant event occurs, risk management interviews relevant parties, coordinates responses from appropriate hospital departments, and leads a root cause analysis if deemed necessary. The framework for risk management’s improving hospital processes is driven by compliance and accreditation. This narrowing of my population and opportunity led me to my final needs statement iteration:

Hospital Risk Management teams who seek to track compliance and meet accreditation standards need consistent and detailed event reports on near misses and medical error-related events.

- Population: Hospital risk management departments

- Opportunity: More data needed for systems-level quality improvement and compliance tracking to maintain accreditation

- Outcome: An accessible tool that enables clinicians to consistently and easily report near misses or medical errors that do not result in serious harm

Week 4 Blog: Endotrachial Tube Patent Heading link

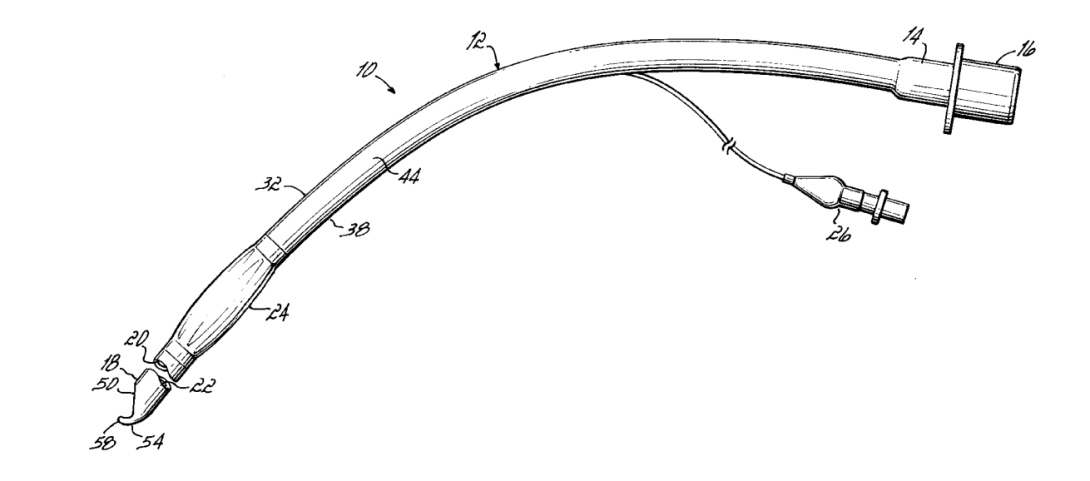

For my patent search, I chose to refine a needs statement related to intubation that my team came up with during week 3.

Medical professionals who intubate patients may cause damage to airway structures due to irritation from the endotrachial tube, and need a way to smoothly guide the tube into the airway in order to lessen airway damage and reduce pain felt by the patient.

When discussing this needs statement with Dr. Nishioka, he mentioned that he had used ET tube tips that curved inward at the end in order to reduce the likelihood of the tip irritating airway structures as it is guided into the trachea. In his opinion, this makes it easier for the medical professional to perform the intubation because there is less resistance and less force needed to advance the tube down the airway; it is ideal for the patient as well because they experience less trauma in the process and feel less pain afterwards.

In my research into curved ET tube tips, I came across US patent no. 5,873,362 for the Flex-Tip endotrachial tube from Parker Medical. It describes “An endotracheal tube (10) having an incomplete posterior bevel (50) extending toward, but not completely through, the anterior wall (36) and a curved lip (54) projecting from the anterior wall (36).” See the attached image for a drawing of the device described in this patent.

In all but the design of the tip, the design in this patent is very similar to the standard ET tubes (ETTs) that I have seen in use this summer. A standard ETT has a beveled edge and does not taper, meaning the tip of the bevel is prone to get caught in structures like the laryngeal inlet or vocal chords. This patent claims that the inward curvature of the Parker Flex-Tip reduces the likelihood that the tube will get “hung up” on airway structures as it is advanced.

From what I have read in this patent and what I have gleaned from interviews with Dr. Nishioka, the Flex-Tip has a well thought out design and achieves what it claims to do. Next I’d like to see it in action, perhaps in use by a professional who has only used standard ETTs in the past, to get an idea of a first-time user’s experience with the design.

Week 5 Blog: TAM Heading link

For my market analysis, I chose to focus on a needs statement that came to mind this week in clinic. On the surgery floor, patients are constantly being wheeled in beds as they go from pre-op to the operating room to recovery. Sometimes, these beds can be difficult to maneuver and this week I watched a patient bed bump into a piece of equipment while rounding a tight corner. These observations inspired the following needs statement:

Employees who move patients in beds around the hospital may have difficulty maneuvering tight corners and need hospital beds that are more easily steered to minimize the risk of bumping into objects and/or people.

In order to begin sizing the hospital bed market, I looked at the IBISWorld report on the hospital bed industry. Key takeaways from this report were that it has $2.6B in revenue and there are 3 major competitors in the industry: Hill-Rom, Stryker, and Invacare, in order of market share highest to lowest.

To calculate units per year, I first found that there are 920,531 staffed hospital beds in the country (1). I also found that the average lifespan of a hospital bed is around 5 years in circulation (2). If every hospital bed in the country is expected to turn over every 5 years on average, then the number of hospital beds purchased per year would be around 920,531/5 = 184,106 beds per year.

Currently, there is a huge range in the cost per bed depending on the features of the bed. Manual beds cost less than semi-electric beds which cost less than fully electric beds. Recently, the “smart bed” industry has been gaining traction (3), which is comprised of beds with sensors that can communicate with the EHR and can sense if a patient is a fall risk. Stryker claims that their smart beds are guaranteed to reduce falls by 50% (4).

All of the hospital beds that I have seen at UIHealth are fully electric beds, and while this may not be the case at care centers across the country, I chose to use this as a measure in order to calculate a cost per unit for a potential solution. My search results told me that $2,000 is an appropriate cost per unit for a fully electric hospital bed.

Putting this all together, my total addressable market = (184,106 beds per year)*($2,000 per bed) = $368M

Sources:

- https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2022/01/fast-facts-on-US-hospitals-2022.pdf

- https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region6/69100080.pdf

- https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2022/07/21/2483869/0/en/Healthcare-Smart-Beds-Market-Size-to-Reach-USD-1-166-Million-by-2030-Fueled-By-Growing-Improvements-in-Patient-Care-Says-Acumen-Research-and-Consulting.html

- https://www.stryker.com/us/en/acute-care/products/procuity/index.html

Week 6 Blog: Reflecting on CIP Heading link

As CIP comes to a close, I am amazed at both how quickly the program flew by and also how much learning we packed into 6 weeks. I have learned so much from our faculty and my peers this summer; the significance of interdisciplinary collaboration was really evident as our team worked together to parse a clinical need.

One area of growth that I found particularly challenging and rewarding was the process of constant observation. Observation to me sounds like it could be a fairly passive practice, but in the first few weeks I came to find that my brain was constantly “on” in clinic, noting tiny things to bring up later and formulating questions to research on my own. Being dropped in a completely new environment, almost everything seemed noteworthy and I filled up my entire pocket notebook in the first week of the program. Through practice I learned to take better notes, to better filter out true needs from noise, and how to efficiently get answers to my questions.

Because of the short duration of the program, the transition to immersion can feel overwhelming for someone without lots of experience in clinical spaces. I had not spent much time in the OR prior to this summer, and I felt quite out of place on the first day which definitely hindered my observational abilities. My advice to future CIP students is to be respectful and direct when working with mentors and other clinicians– it’s often the case that they don’t have much time, and I found that clinicians appreciated and were most responsive when I was quick to get to the point with my questions. I most often began with “Hi, my name is Sitara and I’m a student shadowing this summer. Is this an ok time to ask you a question?” This technique worked best for informal, on-the-spot interviews, and allowed me to gauge immediately whether I could ask further questions or if it was more appropriate to quietly observe.

Lastly, I would advise every CIP student to really engage with each of the exercises that we did in the classroom, even if it doesn’t quite align with their skill set or interests. Personally, I did not know much about market analysis before this summer and I am still no expert in the area, but having some hands-on experience in the area was extremely valuable. I now feel much more confident about my ability to understand and talk about business viability. All of these activities serve to increase your literacy in unfamiliar areas; some may feel more valuable to you than others, but overall they make you a better team player in any interdisciplinary endeavor.