Neil Sundaram

Student Participant

Week 1 Heading link

During the first week in the Dry Eye and Ocular Graft vs Host Disease (GVHD) Clinic with Dr. Jain, my fellow teammates and I were immersed in a variety of patient presentations and illnesses. Throughout our time in clinic, our job was to observe the patient-provider interactions and question the current standard of care. “Are we solving problems and taking care of patients in the most efficient and safe way possible?” Our week started off with productive conversation around the needs of the Dry Eye Clinic eventually narrowing in on the need for how to best measure ocular redness. In this discussion came the understanding of how to distinguish incremental innovation from transformative innovation and begged the question, “what will we dare to attempt at the end of our 6 weeks?”.

For me, an important aspect of problem solving is the understanding of why a new solution is needed. Within the context of this clinic, there are many downstream impacts of accurate and precise ocular redness such as proof of concepts for medications, titrating treatments for patients, and expansion of treatment to other specialties (Is a slit lamp always necessary to treat ocular presentations of diseases?). With this broader understanding in mind, I would like to visit some of the good and bad designs in the clinic today.

Good Designs:

The slit lamp used in clinic is a very complex piece of equipment that every ophthalmologist will know how to use. Although I was not able to pinpoint any faults with the equipment itself, I was able to appreciate some of the better aspects of its design. The slit lamp has an almost never-ending set of dials and knobs that can be used to shift, focus, and zoom in or out of the different layers of the eye. In my experiences this week, I did not record any difficulties on Dr. Jain’s side when using the slit lamp for any of his patients, attesting to its great design.

Designs with potential for improvements:

In the Dry Eye Clinic, the Oculus Keratograph is a device uses for measuring ocular redness that has potential for both incremental and transformative innovations. One large area for improvement is the standardizing the region of the eye that is captured during the imaging process. Too frequently, the eyelid margins interfere with the readings and are captured on the patient leading to falsely normal eye redness readings. Additionally, the image captured cannot be manually set and does not account for variations of eye sizes and shapes when capturing redness (Further suggestions for improvements will be discussed in later weeks).

Another innovation that could use some improvement is the aesthesiometer as it can be very discomforting for patients. This piece of technology is in the shape of a pen with a fine tip at the end. The sturdiness of the tip is adjusted to assess how sensitive a patient’s cornea truly is. From the patient point of view, they are about to get poked in the eye with something that looks potentially very sharp. Over the next few weeks, I plan to brainstorm other methods of achieving the same data while causing less stress and physical pain to the patient.

Week 2: Storyboarding Heading link

This week our group was given the opportunity to shadow around various floors in ophthalmology to better understand the multidisciplinary process of end-to-end patient care. Our itinerary consisted of joining Dr. Shorter in the contact lens department on Wednesday, revisiting our home base of the dry eye clinic on Thursday, and finally wrapping up with Dr. Tran in oculoplastic surgery on Friday. Although this week was less structured that the previous, I was pleasantly surprised by the variety in both procedural work and patient contact that I was able to see.

In terms of tangible goals, I sought out to identify one technology or process among the various clinics that would be applicable to our question from last week of how to better measure ocular redness. The thought came almost immediately from Dr. Shorter’s clinic while she used the Oculus Pentacam to create an image-based design for a patient’s personalized contact lens. This patient had a condition known as keratoconus that made it difficult for them fully open their eyes, much like the patients in the dry eye clinic. Due to the patient being unable to maintain appropriate eye width for the corneal scanning, Dr. Shorter used a Q-Tip like stick known as an Oculus LidStick to manipulate the eyelid in such a way that would allow her to capture the necessary dimensions to create the contact lens.

Initially I thought this would certainly be a cheap and simple solution that could aid with the inconsistencies of corneal capture during oculus keratography, but after speaking with Dr. Jain I learned that the two technologies did not have the same user needs. The Keratograph back in the dry eye clinic was an older model and needed the user to dedicate both hands to device to scan for the most precise image.

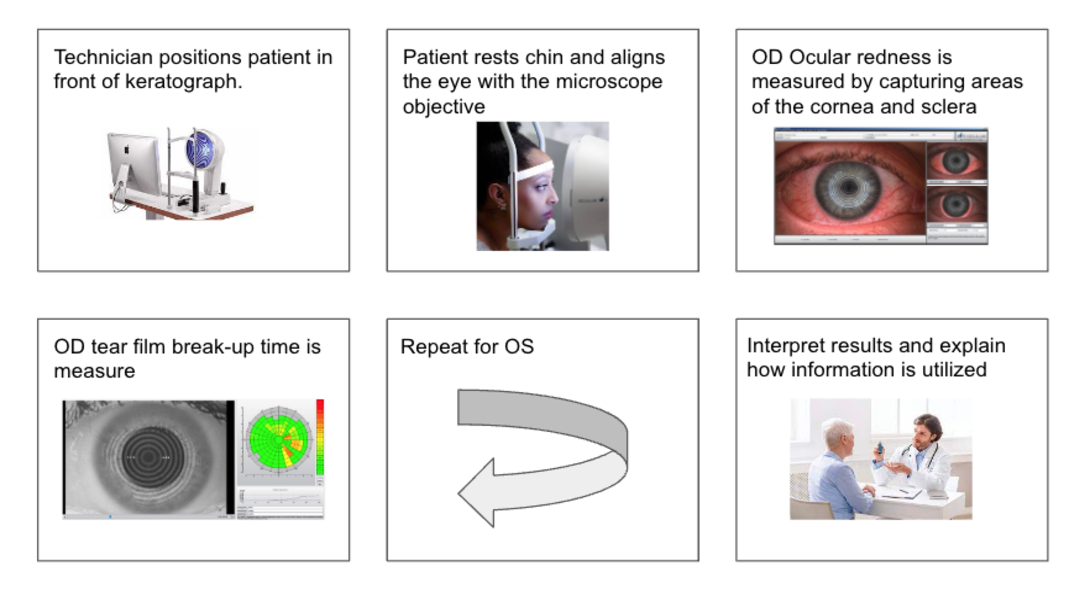

Taking a step back to think about where the issue lies in Oculus Keratography, I decided to create a storyboard:

(see image)

In this storyboard I lay out the steps in simple terms and think about where the important issues lie. Is the main issue the imaging of the eye, meaning that the area of capture needs to be standardized? Or should I be thinking broader about what is the best way measure redness and set aside all prior knowledge of imaging and its capabilities. This is where I turn to the literature.

When taking a step back to think of other ways to measure redness with teammates, we came across an existing technology called Vita Easy Shade Spectrophotometer that detects shades of color in teeth. While the Easy Shade has been supported to work in dental practice and research, we think there is potential for this technology within ophthalmology. Over the next week we will discuss plans to research the technology this company is using and see if those concepts can be directly applied to either improving existing ophthalmic technology or creating something entirely new.

Week 3: Needs Statement Heading link

With some basic introductory knowledge of the ophthalmology department under my belt, this week I focused on interviewing various members of the healthcare team. The interviews consisted of residents, fellows, and technicians within oculoplastic surgery, neuro-ophthalmology, and contact lens. During interviews, I noticed a theme of 1. needing to improve patient scheduling to reduce patient wait time and subsequent irritability and 2. Wanting to improve the patient comfort during various exams. At a bird’s eye viewpoint these seem like rather obvious statements, but for the sake for completeness I will choose to address the second need and narrow in on my clinical experiences from the Dry Eye Clinic with Dr. Jain.

From what I have observed, the method of corneal sensation measurement within corneal services requires improvement. I discussed this briefly in my week 1 clinical findings, however the extent to which I have seen patients’ reactions to the aesthesiometer have increased. As a reminder, an aesthesiometer is a pen with nylon thread tip that varies in length yielding to differences in firmness of the tip. To the patient, this can look like a very sharp object approaching their eye. Some alternative forms of measurements have been explored in the past and so I will focus on the innovation that leverages pressurized air to mimic the results of the aesthesiometer.

For my first iteration of a needs statement, I propose a less invasive test for corneal sensation for technicians with unsteady hands:

Ophthalmology technicians with unsteady hands can benefit from a less invasive form of measuring corneal sensation and reduce rate of patient dissatisfaction.

While this largely addresses the need and gives a tangible measurement of success, this scope of the population is too narrow. This problem exists outside the realm of technicians with unsteady hands. Additionally, the measurement of patient dissatisfaction could be further specified towards Dry Eye Clinic (DED) visits.

Ophthalmology patients afraid of needles require a less invasive form of measuring corneal sensation to reduce stress levels associated with Dry Eye Clinic visits.

In this iteration, I changed the population group to ophthalmology patients and specified patient dissatisfaction with stress levels associated with DED visits. Based on how use of aesthesiometers is described in literature and in clinic, I will return to a population of ophthalmology technicians and stay with stress levels as a tangible measurement of patient dissatisfaction.

Before completing the final iteration of the needs, I thought it would be beneficial to research alternatives to the nylon tip for the basis of the statement. In a retrospective, clinic-based case control study, researchers studied the use of a modified Belmonte gas aesthesiometer that leverages pulsed air jet blasts of CO2. Additionally in the journal of Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science, scientists support an osmatic non-invasive technique of measuring corneal sensation in rats that is believed to be applicable to the human population. These two non-invasive measurements should be further studied and tested in clinical settings for use in corneal services.

Ophthalmology technicians require a less invasive form of measuring corneal sensations to reduce patients’ stress associated with DED clinic visits.

Nathan Efron; A Proposed New Measure of Corneal Sensitivity. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016;57(6):2420. doi: https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.16-19721.

De Paiva, Cintia Sade, and Stephen C Pflugfelder. “Corneal epitheliopathy of dry eye induces hyperesthesia to mechanical air jet stimulation.” American journal of ophthalmology vol. 137,1 (2004): 109-15. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00897-3

Repurposing Existing Spectrophotometric Technologies for Assessing Bulbar Redness in Dry Eye Clinic... and my week 4 experiences Heading link

This week in ophthalmology clinic was unlike others in that I spent extra time, outside my normal hours, at the Eye and Ear Infirmary (EEI). For the most part, I enjoyed some 1-on-1 time with various residents at the General Eye Clinic (GEC), arguably the most hectic part of the EEI. Each day nearly 100 patients are seen all between 8 am – 4 pm, and I couldn’t believe it.

On Thursday evening and Friday morning, I spent time shadowing Dr. Charlie Frank, a PGY-4 resident. In hindsight, following a resident is both gratifying and stressful. They are tasked with what feels like a balancing act of endless patient visits and paperwork while also managing scheduling/follow-ups and the inevitable hunger pangs from running around all day.

If anything, these experiences made very clear why throughout every interview “patient scheduling” and “staffing” were mentioned as problems that needed fixing at the EEI. In the GEC, the last patient is scheduled for 3:00 pm but is usually seen at 5:30 pm or later.

It can be quite frustrating to observe such hard work by both clinicians and patients alike but knowing that the solution is likely outside the scope of something my team and I can innovate. Managing administration and implementing a better scheduling system would likely take years to accomplish and may not even be truly “fix” the issues the ophthalmology teams face. That being said, I try to compartmentalize and focus on uncovering more user needs, potentially one where there is opportunity for a tangible solution.

Before attending the GEC, I was expecting to encounter an array of equipment insufficiencies and outdated workflows used to assess patient health. However, when shadowing Dr. Frank, I was made aware firsthand how practice does make perfect. A previously identified problem within most ophthalmology clinics was the variability in time taken to locate the optic nerve with a handheld retinal lens under slit lamp microscopy. Although most first and second year residents struggled with this task, Dr. Frank and his attending Dr. Aref both focused on the optic nerve with ease. In fact, I understood the handheld design after noticing how important it is to maneuver the patient’s head and eyelids in cases of photosensitivity or photophobia.

At this point, my leading design flaw within the ophthalmology department is the objective measurement bulbar redness by the Oculus Keratograph. When reviewing literature of alternative forms of objective redness/erythema measurement, applications of colorimetry, laser doppler flowmetry (LDF), and diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) are typically found within practices of dentistry and dermatology.

The patent I will discuss is regarding the VITA Easyshade® V and related to spectrophotometry technology. This instrument measures a spectral distribution of lights and converts the value into a tristimulus value represented by a numerical value. There is potential in repurposing this technology too objectively measure bulbar redness, and output a continuous value as opposed to the subjective Validated Bulbar Redness (VBR) score used in clinic today. The concepts of lightness, chroma, and hue should be further studied under the context of ocular redness measurement.

VITA Easyshade® V is protected by one or more of the following US patents

(6,040,902; 6,233,047; 6,239,868; 6,249,348; 6,264,470; 6,307,629; 6,381,017;

6,417,917; 6,449,041; 6,490,038; 6,519,037; 6,538,726; 6,570,654; 6,888,634;

6,903,813; 6,950,189; 7,069,186; 7,110,096; 7,113,283; 7,116,408; 7,139,068;

7,298,483; 7,301,636; 7,528,956; 7,477,364; 7,477,391) and others patents in the United States and other countries.

Week 5 Heading link

In the final week of the Clinical Immersion Program, I focused my efforts on a literature review for our final project proposal: To objectively quantify bulbar redness. With the assistance of Dr. Jain and his Dry Eye Clinic team, I was able to understand the complete process in measuring bulbar redness using the Oculus Keratograph 5M and identify both strengths and weaknesses of the design. In this problem space, there is a specific need for a precise measurement of ocular redness to accomplish several downstream outcomes. Primarily ophthalmologists are concerned with better understanding the inflammation in the eye and more specifically the patient response to treatment for that inflammation. In addition to this, quantifying ocular redness has applications in titrating treatments and even proving efficacy of novel drugs. With this problem space appropriately defined, I present the following needs statement:

Ophthalmologists struggle with measuring bulbar redness as a proxy for inflammation and desire a precise methodology to quantify progression of ocular disease to better titrate patient treatment.

To explore this problem space further, this week we were tasked with calculating a Total Addressable Market (TAM). By design, the Oculus Keratograph is a technology that was made to be a singular purchase by each clinic. In this sense, the traditional TAM will not fit as cleanly as it might for a one time use innovation (e.g. glass pipette), and so I will calculate the TAM using number of uses of the device per patient in one year. According to UpToDate, in 2022 Dry Eye Disease (DED) affects nearly 16.4 million Americans. If we assume that the average DED patient visits their provider 5 times in one year and receives an imaging procedure each time, then we can now calculate the TAM using a base price of $20 per image and reach a total of 1.6 Billion USD (16.4 million * 5 visits * $20 = $1.6 Billion).

Week 6: CIP Final Thoughts Heading link

The clinical immersion program at UI Health served as a pleasant reminder for my passion to pursue medicine. For the past 6 weeks, I was able to reflect on what excited me the most about my future in the healthcare field. From complicated multidisciplinary patient cases to genuine patient-provider interactions, I appreciated these moments as opportunities to learn what life can be for a medical provider. On the more academic side of my experiences, I enjoyed listening to my colleagues discuss their problem spaces in medical disciplines that were different from my ophthalmology experience. It served as an engaging way for me revisit some of the medical topics introduced during our M1 year.

For the future students interested in this program , I recommend always keeping an attentive ear and to fully lean into the natural curiosity that will accompany the clinical experience. At the risk of sounding too cliche, I do believe in “What you put in is what you get out”, especially at UI Health. I look forward to seeing how this experience will help shape the rest of my medical training at UIC.