Haari Sureshkumar

Medical Student

Email:

Week 1: Learning about Anesthesiology Heading link

For our first week in the Clinical Immersion program, our team mainly shadowed anesthesiology in the operating room environment for all three days. We had the chance to observe the role that anesthesiology plays in a variety of different procedures, including OBGYN procedures and outpatient procedures. Throughout all of our experiences, we began to gain an appreciation of how the anesthesiology team operates and interacts with the rest of the staff in the operating room. Namely, we began to learn about their workflow for making clinical decisions and the extent to which the anesthesiology team interacts with their technology to make these decisions. Some designs that stood to me are listed below:

Good Design: Video Laryngoscope in Intubation

Activities: The video laryngoscope is operated by either an anesthesiologist or CRNA, who first connects the video laryngoscope to a monitor on a stand. After the patient is sufficiently anesthetized, the user guides the blade of the laryngoscope down the patient’s throat while using the video on the screen to guide them. After the laryngoscope is in the correct location, the user then takes an intubation tube and uses the blade of the laryngoscope to guide it to the appropriate location in the patient’s throat. This device is indicated for use when the patient is suspected to have a potential obstruction during the intubation process. For example, in the specific instance that I witnessed its usage, the patient had loose teeth so the anesthesiologist opted to use the video laryngoscope to make sure that they do not knock off any of the loose teeth during the intubation process.

Environment: From what we observed, for the anesthesiology team, this device is mainly used in the operating room environment during the preparatory phase of the surgery.

Interactions: The main interactions that take place is when user turns on the standing monitor and connects it to the video laryngoscope. Furthermore, another interaction that occurs is when the user guides the blade of the laryngoscope down the patient’s throat and uses the video feedback on the monitor to help them.

Objects: The objects used in this procedure are a monitor on a stand, the video laryngoscope, and the intubation tube.

Users: The main users of this device are anesthesiologists and CRNAs.

I thought the video laryngoscope had a particularly great design as it still presented in the same form factor as a normal laryngoscope, meaning that there is not a difference in how the scope is inserted into the patient’s throat. In other words, there is a minimal learning curve when learning how to use a video laryngoscope if the user already knows how to use a normal laryngoscope.

Bad Design: Nasal Intubation

Activities: In order to do a nasal intubation, one person (usually an anesthesiologist or CRNA) must hold the intubation tube with one hand and use the other hand to guide the end of the tube down the nostril with forceps. As this happens, a second person is needed to push the intubation tube downwards. Nasal intubation is typically indicated when the surgical site is in or around the mouth, in which intubation via the mouth would be obstructive for the surgeons. In the specific case that we saw, the patient was undergoing a jaw surgery. Thus, the anesthesiology team opted for a nasal intubation so that the tubing would not be in the surgeon’s way.

Environment: This procedure typically happens in the operating room environment.

Interactions: The main interactions that take place is between the anesthesiologist, the forceps, and the intubation tube. Another interaction that occurs is between the person is intubating and the second person who is pushing the intubation tube down.

Objects: The objects involved in this procedure are the nasal intubation tube and forceps.

Users: The users in this procedure are anesthesiologists and CRNAs.

In a nasal intubation, three total hands are needed because one person needs to hold the intubation tube and use forceps to guide the tube down the patient’s nostril while a second person is needed to push the tube downwards. Usually, if a patient needs to be nasally intubated, it is because the surgeons are operating in or near the mouth. Thus, having two people intubate can be quite obtrusive to the surgeons who are prepping the surgical area. Although this may seem like a minor nuisance, this can lead to a longer surgical preparation time and a longer amount of time that a patient is underneath general anesthesia. The three hands involved in a nasal intubation are usually an anesthesiologist/CRNA and a second individual with a free hand.

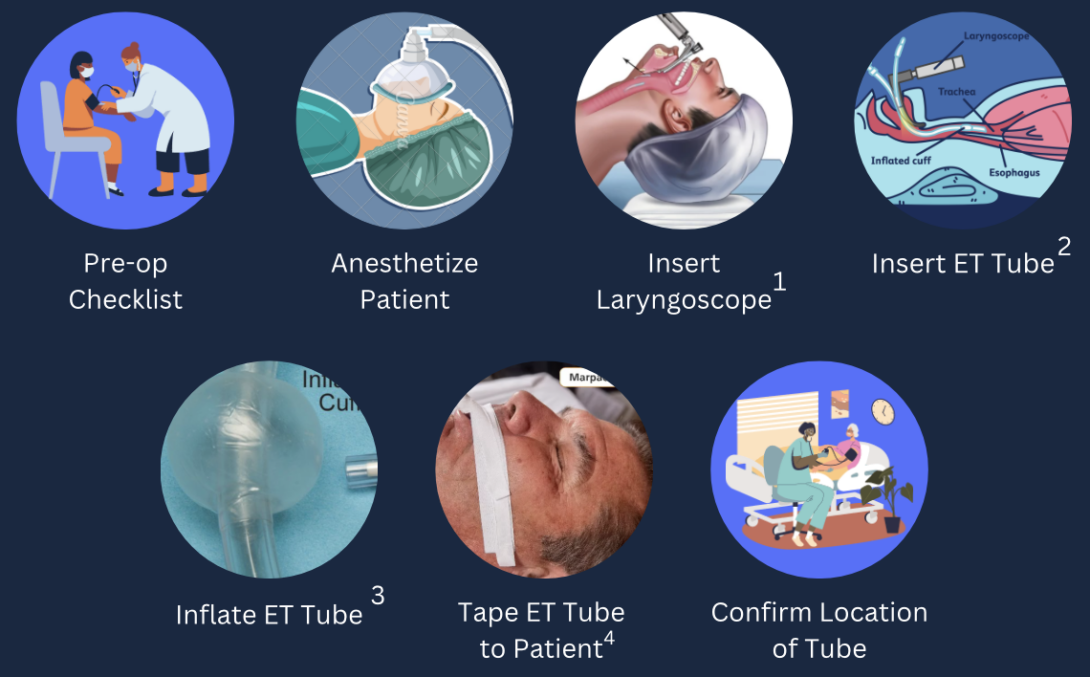

Week 2: Intubation Storyboard Heading link

After watching many interesting surgeries this week (craniotomy, vitrectomy, etc.), it became clear to me that a standard procedure that is always done at the beginning is intubating the patient. I also observed a resident intubating a patient this week for the second time, which inspired me to think about the teaching process for intubation. In this week’s post, I will briefly discuss the major steps in intubating a patient and common problems when teaching intubating a patient (Satyapal et al.).

Step 1:

The very first step before the intubation process may begin is going through a pre-operation checklist with the patient. This pre-operation checklist involves checking the vitals one last time, and asking the patient for brief past medical history.

Step 2:

The next step involves moving the patient and transferring them into the OR bed. At this point, the anesthesiologist will apply a mask to the patient and put the patient to sleep. In order to put the patient to sleep, the anesthesiologists often administer a gas through the mask or a propofol drip through an IV. Additionally, the patient also receives oxygen through the mask. A common pain point during this step is that propofol is often described as “spicy” which can lead to patient discomfort as it goes in.

Step 3:

After the patient is fully asleep, the anesthesiologist then tilts the patient’s headlock and inserts the blade of the laryngoscope into the patient’s throat through the mouth. The anesthesiologist at this time must be careful to avoid knocking out any teeth or other structures while inserting the blade of the laryngoscope. This step is often difficult for many learners as it is difficult to guide the blade down the throat without knocking structures like the teeth.

Step 4:

Afterwards, the anesthesiologist inserts the ET tube using the laryngoscope as a guide. After the ET tube is placed, the anesthesiologist must remove the stylet. The stylet is what allows the tube to keep its rigid shape so that it easy to insert down the throat of the patient.

Step 5:

After the ET tube is placed, the laryngoscope is removed. Then, the anesthesiologist must inflate the cuff of the ET tube. The inflation of this cuff ensures a proper seal in the throat so that all movement of gases occurs only through the tube.

Step 6:

Afterwards, the tube is taped to the side of the patients cheek to secure the tube so that it doesn’t fall out. Then, the tube is connected to the ventilator.

Step 7:

The last part of the intubation process is that the anesthesiologist needs to confirm the location of the ET tube. There are two main ways to accomplish this: the first way is to use a stethoscope to check for breathing sounds and the second way is to check for adequate rise and fall of the chest in relation to the ventilator.

Review Article Summary

The review article that I chose relates to the education of students and residents in intubating a patient. Satyapal et al. describes frequent mistakes or “pain points” that learners undergo when learning the intubation process. These mistakes are often incorrect head positioning if the patient is not on a pillow, being distracted by incorrectly holding tools if given them to them by the assistant in an odd way, and improper understanding of esophageal and endotracheal anatomy. The article suggests that these mistakes can be reduced by the use of simulator training and education of the anatomy before doing the procedure on a real patient.

Reference:

VM Satyapal, CC Rout & TE Sommerville (2018) Errors and clinical supervision of intubation attempts by the inexperienced, Southern African Journal of Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 24:2, 47-53,DOI: 10.1080/22201181.2018.1435385

Week 3: Needs Statement Heading link

With the basics of roles and responsibilities of the anesthesiology team under my belt, I spent a lot of time this week reflecting and reviewing what I have seen in my time with the anesthesiology team so far to identify a need or an area of improvement in a procedure or process that I have seen. One procedure that really stuck out to me was the placement of an epidural. During my first week with the anesthesiology team, I had the two opportunities to observe an epidural in the OB/GYN department and ask the anesthesiology team about difficulties with the procedure. In addition, I also had the chance to attend a lecture given by an OB/GYN anesthesiologist about the different types of anesthesia given to pregnant patients.

From what I garnered, the most common way to check for correct placement of an epidural needle in a pregnant patient is to do a lost of resistance (LOR) test. the LOR test requires the anesthesiologist to slowly advance the epidural needle into the patients back. This needle is attached to a glass syringe filled with saline and the anesthesiologist will continuously push the plunger of the syringe in. If the plunger bounces back, then the anesthesiologist knows that they are not in the correct epidural space. Once the anesthesiologist pushes the plunger of the syringe in and it does not bounce back, they know that they might be in the correct place as there is a loss of resistance. There are better methods of confirming correct epidural catheter placements, but these are not feasible in pregnant patients.

The issue with this method is that it might take longer and does not always confirm correct placement of the epidural catheter. Thus, I chose to focus on this issue for my needs statement.

Needs Statements

First Iteration

Anesthesiologists need a better way of confirming that they are in the epidural space when placing an epidural catheter in a pregnant patient.

The population in this case are anesthesiologists as they are able to place an epidural in pregnant patients. The opportunity described here is a better way of confirming that they are in the epidural space when placing an epidural catheter. The outcome would be the correct placement of the epidural catheter.

Second Iteration

For the second iteration, I considered what does “better” mean in the placement of an epidural catheter? I realized that in my reflection of this procedure that what I identified as an issue is the LOR test is long and not reliable. Thus, the opportunity is now a quicker and more reliable method of confirming correct placement. I also tried to make this iteration more clear and concise.

Anesthesiologists require a quicker and more reliable method of confirming the correct placement of an epidural catheter in a pregnant patient.

Third Iteration

For this third iteration, I realized that using location of placement as the outcome is not necessarily a measurable outcome in pregnant patients. For this iteration, I chose to use analgesia as an endpoint for correct epidural catheter placement. Additionally, after doing more reading, I realize now that other specially trained healthcare professionals can also place an epidural in pregnant patients.

Qualified anesthesia providers require a quicker and more reliable method confirming correct placement of an epidural catheter for analgesia in pregnant patients.

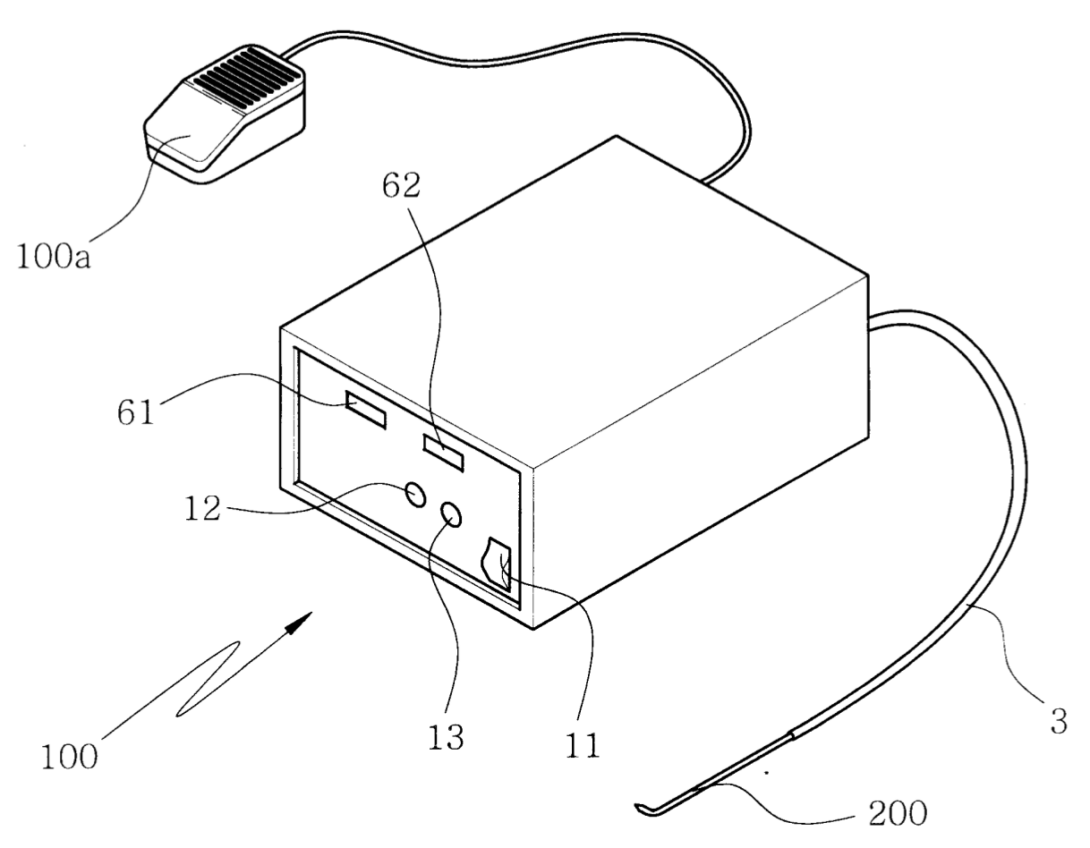

Week 4: Patent for Epidural Placement Confirmation Heading link

For my patent search, I decided to pursue a patent search for the needs statement that I had created last week:

Qualified anesthesia providers require a quicker and more reliable method to confirm the correct placement of an epidural catheter for analgesia in pregnant patients.

As described in the last blog post, the current method of confirming correct placement is by using a fluid filled syringe and checking for a loss of resistance by pushing the plunger of the syringe in. The issue with this method is that the qualified anesthesia provider would need to make small advancements and check for loss of resistance, which can be very time consuming. In my patent search regarding this topic, I had come across a patent filed in South Korea describing a device to confirm the correct placement of the epidural catheter (KR20022788Y1). The device claims to use an air compressor to deliver compressed air within the tubing of the epidural. Inside the device, there is a pressure sensor that is responsible for detecting the pressure of the compressed air within the tubing. The pressure that is detected within the device is displayed on a monitor. Once the pressure has dropped significantly, the device will create an alarm or beeping sound to indicate to the user that they are now within the epidural space.

From what I have understood from this patent, this seems to have potential in addressing the needs statement. The device would continually check for change in pressure as the user advances the needle. This solves the time consuming process of the user currently advancing the needle a little, stopping, and checking for a loss of resistance. However, the use of this device would need to be validated for use within the pregnant patient population, as the patent only describes the use of device for epidurals in the general patient population.

Week 5: Total Addressable Market (TAM) Heading link

This week, we were tasked determining the total addressable market (TAM) in relation to a particular needs statement that we create. For this task, I used the following needs statement:

Qualified anesthesia providers require a quicker and more reliable method of placing an epidural catheter for drug delivery in pregnant patients.

To start off my market research, I first investigated the Epidural Catheter Market Research Report from Precision Reports. In 2022, the market size was estimated to be worth 58 million USD and is projected to grow to 76 million USD by 2028.1 The key leaders in this market are Becton Dickinson, Smiths Medical, Telefax, and B. Braun.

To calculate units per year, I first started with the number of births per year in the United States, which was around 3.66 million.2 Moreover, it is estimated that around 75% of pregnant individuals in the United States get an epidural catheter for pain relief.3 Thus, to figure out the number of epidural kits that are used per year, we can assume that around 3.66 million*0.75=2.745 million kits are used per year in pregnant patients. The average cost. After looking into the cost of an epidural kit from the different key leaders in the market, $500 dollars seems to be an appropriate cost for estimating the cost of an epidural kit. Thus, the TAM is 2.745 million*500 = 1.373 billion. Thus, if an individual is able to create a better kit for the placement of an epidural catheter, the TAM that they are able to address is 1.373 billion.

Week 6: Concluding Thoughts Heading link

As CIP comes to a close, I was shocked by how quickly the program came to a close and how much we learned about the hospital system. Through our 6 weeks, we identified a need for an improved non-invasive hemodynamic monitoring system that decreases the rate of error in blood pressure readings when external interferences occur.

Overall, I greatly appreciated the opportunity that CIP has given us. Through CIP, we got to learn more about Anesthesiology and the big picture of how the operating room floor works day to day. We all had the opportunity to talk with many members of the Anesthesiology team at UI Health and get differing perspectives on the systems in place at the hospital. Regardless of whether a future CIP participant was a medical student or a biomedical engineering student, our entire group felt that this experience was very enriching.

To the future CIP members, my advice would be that you get out what you put in (as cliche as that may sound). Everyone at UI Health is willing to explain or teach you as long as you put in the work and effort to ask questions and stay actively engaged with what is going on around you.