Elizabeth Troy

Student Participant

Blog Post: Week 1 Heading link

This week I have enjoyed the opportunity to shadow in the Dry Eye and ocular GVHD Clinic at UIC. I believe this clinic is unique in its integration of patient care and research. The approach of the clinic is a design that I can learn a lot from. I look forward to what I will be able to learn over the summer during this program.

My experiences this week have led me to think about several concepts related to design:

First, what makes a good design? What makes a bad design? This week we were given the prompt to identify two good designs and two designs that could use improvement. I have seen many devices, processes, and structures in the clinic this past week. I think there are a lot of questions to ask when evaluating a design, including questions about use, need, reliability in both operation and measurement, how people interact with them, and who can use them. One of my favorite designs that I have seen this week is the slit lamp microscope. There are many positives to the design of the slit lamp microscopes I saw this week. My favorite thing is that several images are captured at once in rapid succession when prompted and the physician is able to select an image from the set to save if the “main” image is blurry due to movement.

The second is accessibility. An innovation should be able to reach the people it is designed to help. Typically, many people tend to think of accessibility in terms of disability. This is a limited view of accessibility, but it is incredibly important. Many spaces, devices, and processes are designed without disabled people in mind, which limits their use and ultimately disadvantages disabled people. While I was shadowing this week, I learned that some of the doorways in the clinic are not wide enough to fit a wheelchair through because the clinic was designed before ADA guidelines came into effect. The clinic is not able to widen the doorways because the clinic was built during the time that asbestos was used for insulation. Yesterday, while waiting for the train, I witnessed someone in a wheelchair struggle to get door open before going through it because the L station I was at did not have an access switch for the station exit. (I was on my way to offer to help, but they got through the door before I reached them). This prompted a conversation between my friends and me about older stations and poor design choices regarding accessibility. While access for disabled individuals is an important component of accessibility, other components should also be acknowledged, especially financial accessibility. If a patient cannot afford a therapy, they may not get the treatment they need or they may get bankrupt. Another component is whether or not designs are accessible to a diverse set of body types. Some designs that I have seen make me wonder if this component was considered. When practicing user-centered design, I believe it is important to include a diverse set of users. Otherwise, there is a risk of alienating people. When these people are patients, there is a risk of systematically delivering sub-optimal care.

Blog Post: Week 2 Heading link

This week was very exciting. Not only was my team able to shadow in the Dry Eye Clinic, but we were also able to shadow in the contact lens clinic and an oculoplastics OR. I really enjoyed getting to see new sides of opthomology, and I hope to see more soon.

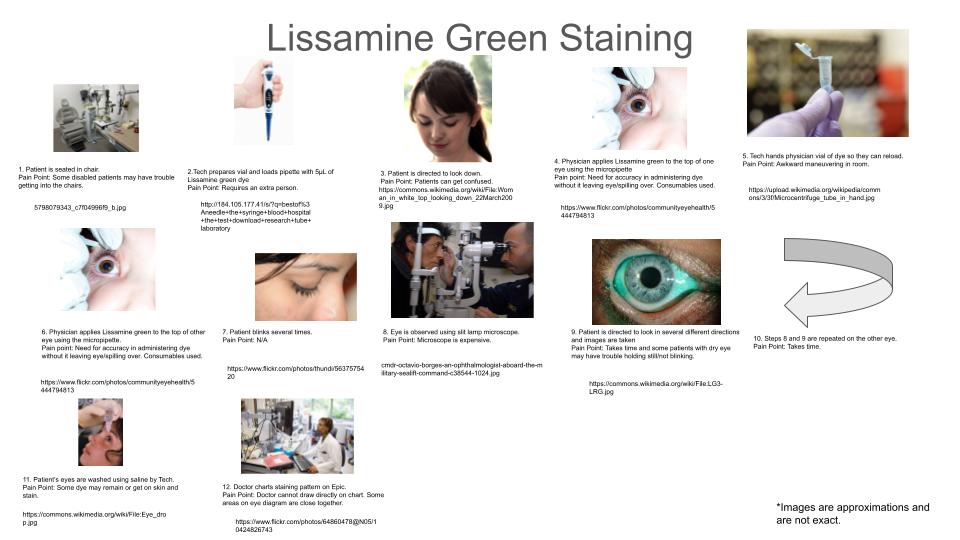

This week our assignments were to create a storyboard and identify a peer-reviewed paper that is related to the storyboard. For this week, I decided to create a storyboard on ocular lissamine green staining. Lissamine green is a dye used in the diagnosis of dry eye disease, which stains cells with damaged membranes. The use of the dye in the clinic is detailed in a storyboard below with pain points and citations listed underneath each step. What stands out to me about this process is that a patient’s eyes and skin can remain stained. I wonder if there is a way to administer this dye or wash it out completely afterward without patients leaving the clinic a little bluer.

In order to better understand the role of lissamine dye, I found the paper, Update in Current Diagnostics and Therapeutics of Dry Eye Disease, by Thulasi et al.. The paper covers the advantages and disadvantages of several advancements which could affect the diagnosis and treatment of dry eye disease. Advancements of interest in dry eye disease diagnosis include measuring tear osmolarity, measuring inflammatory biomarkers, imaging the meibomian glands, and optical coherence tomography. A common point of pain with diagnostic methods seemed to be variability or noise within the data.

The citation for the paper is as follows:

Thulasi P, Djalilian AR. Update in Current Diagnostics and Therapeutics of Dry Eye Disease. Ophthalmology. 2017 Nov;124(11S):S27-S33. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.07.022. PMID: 29055359; PMCID: PMC6660902.

Blog Post: Week 3 Heading link

Ophthalmology is a very diverse field. At first, I did not realize how diverse it is, but, after three weeks, I am beginning to appreciate how diverse the field is. The ophthalmology clinics and OR (operating room) that my team has seen house many moving parts and people. These people and parts are not all the same. Some of these people have common goals and needs, while some of them have very different goals and needs. This can be seen in the tools different clinicians use. I saw several cautery pens while shadowing occuloplastics in the minor OR, but I did not see any while shadowing in the Dry Eye clinic. On the other hand, I saw slit lamp microscopes in several different clinics. These differences and similarities in tools are driven by the needs of the people in these clinical spaces. In innovation, it is important to identify these needs. One way to do so is in a needs statement.

In lecture this week, Dr. Brown and Dr. Felder covered the topic of needs statements. A “good” needs statement makes a population, opportunity for improvement, and an outcome that innovators are trying to achieve explicit. The goal of doing this is to identify a need without constricting yourself to any specific solution. You should know what you need to do, while still being able to think outside the box.

With this in mind, I have drafted and edited a needs statement focusing on lissamine green staining – a process that I storyboarded in my blog last week.

Draft 1: Ophthalmology technicians would like to reduce the amount of lissamine green left on patients’ eyes and skin in order to improve patient experiences.

Population: Ophthalmology Technicians

Opportunity: Reduce the amount of dye left on patients’ eyes and skin

Outcome: Improve patient experiences

Edits: After looking at this statement, I thought that the outcome needed to be more specific. While improving patient experiences is always good, it is too broad of an outcome.

Draft 2: Ophthalmology technicians would like to optimize the lissamine green staining and washing process in order to reduce the amount of dye on patients after staining.

Population: Ophthalmology Technicians

Opportunity: Optimize the lissamine green staining and washing process

Outcome: Reduce the amount of dye on patients after staining

Edits: The opportunity of this statement needed to be broadened because it constrained the solution to the lissamine green staining process. What if the best solution is to use a different process other than lissamine green staining? What if the solution is to use a different dye? These solutions would not be considered by this needs statement. The opportunity and outcome were also too closely tied together. I needed to get into why the opportunity was important. Why do we want to reduce the amount of dye left on patients?

Draft 3: Ophthalmology technicians would like to reduce the amount of colored dye left on patients when they leave the clinic so that patients feel more comfortable with how they look after visits.

Population: Ophthalmology Technicians

Opportunity: Reduce the amount of colored dye left on patients when they leave the clinic

Outcome: Patients being more comfortable with how they look after visits

Blog Post: Week 4 Heading link

This week has been another exciting one. My team and I were able to shadow in the general eye clinic, the contact lens clinic, and neuro-ophthalmology. We were also able to interview a technician from the cornea clinic. Several areas for improvement stood out this week, but issues with contact lenses and patient scheduling stood out the most. Issues with scheduling came up multiple times. Schedules are hard to plan and control because the needs of a patient can be hard to assess before they come in and emergencies can happen, leading to someone new being added to the schedule. With contact lenses, I saw patients struggle to use them. I was able to watch a session in which a patient was taught how to insert and remove contact lenses, where the patient struggled to remove a contact lens. The major issue with putting in and taking out contact lenses for new users seemed to be flinching. It is hard to stay still when you are anxious about something being near your eye. For another patient, their issue with contact lenses was that theirs were not getting wet enough. The doctor that I was following explained that hydro-PEG coated lenses had been invented to help with this problem, but that they do not work for everyone. This made me curious about patents for PEG-coated contact lenses.

I used google patent search to find patents on PEG-ylated contact lenses. One that was especially interesting to me is US20190310495A1, which is titled contact lens with a hydrophilic layer [1]. The main claim of this patent is a way of making a contact lens with two layers of covalently bonded polymer surrounding it to form a hydrophilic layer. Specifically in this patent, the first layer of materials casts a wide net, but can include polyethylene glycol (PEG). The utility of this hydrophilic coating is to make the lens more biocompatible. Specifically, the aim of the coating is to reduce the abrasiveness of the lens, reduce infections, and keep the entire system more moist. For patients who are at risk for corneal abrasions or patients who have dry eye, these contact lenses may be a better alternative. Although if a patient is at a high risk for abrasions or already has an abrasion, these contact lenses probably will not be helpful. I remember shadowing when a patient came in with an epithelial defect on her eye and was told that she had to stop wearing contact lenses because of the risk of them being abrasive. I also remember another patient who had to stop wearing contact lenses because of an infection. I also saw a patient with PEG-ylated contact lenses (although I do not know if they had the coating that was covered in this patent), whose contacts were not remaining wet on the outer surface after blinking. Therefore, while this is an alternative aimed at reducing dryness, abrasions, and infections, it does not eliminate the problem.

Citations:

- Havenstrite, K. L., McCray, V. W., Felkins, B. M., & Cook, P. A. (n.d.). Contact lens with a hydrophilic layer (United States Patent No. US20190310495A1). Retrieved July 24, 2022, from https://patents.google.com/patent/US20190310495A1/en?q=PEG+contact+lens&oq=PEG+contact+lens

Blog Post: Week 5 Heading link

This week, I was able to shadow in the GEC (general eye clinic), but I am writing about a conversation that I observed several weeks ago in the Dry Eye and oGVHD clinic. There was a patient that was recommended to wear protective glasses by a physician when walking in order to avoid wind and allergens getting into her eyes. During the conversation, it was brought up that many patients do not like to wear these glasses outside because they are large and odd looking. Essentially, a lot of people do not like to wear dry eye glasses because they think the glasses are ugly.

Needs Statement:

Population – Patients with dry eye disease

Opportunity – Patients do not like to wear protective glasses for aesthetic reasons

Outcome – Increase adherence to treatments that protect the eye from wind and allergens

Patients with dry eye disease do not like to wear protective glasses outside for aesthetic reasons, so there exists a need to increase adherence to treatments that can protect the eye from irritating wind and allergens.

The total number of patients with dry eye disease in the United States is approximated to be 16.4 million people [1]. Given an estimated annual direct cost per patient of $783 per patient [2], the national cost for directly managing dry eye disease can be estimated to be $12.8 billion dollars, which is a very large amount of money. Not all of this money is spent on dry eye glasses. If we assume that the average price of a pair of dry eye glasses is $40 (a number I estimated from window-shopping online), that every patient gets a pair of dry eye glasses, and that patients replace these glasses every two years on average, the total market for dry eye glasses can be estimated at $328 million annually. In reality, this is probably an overestimation of the total market. Many patients likely do not wear protective glasses and therefore do not purchase them. A large reason for this is aesthetics. However just because people are not reached or using a product does not mean that they cannot. If an option came along that was more aesthetically palatable, I believe that more patients would use dry eye glasses.

TAM (total addressable market) = 16.4 million patients X 0.5 glasses/(patient x year) X $40

= $328 million/year

Citations:

1.Farrand, Kimberly F., et al. “Prevalence of Diagnosed Dry Eye Disease in the United States Among Adults Aged 18 Years and Older.” American Journal of Ophthalmology, vol. 182, Oct. 2017, pp. 90–98. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2017.06.033.

2. Yu, Junhua, et al. “The Economic Burden of Dry Eye Disease in the United States: A Decision Tree Analysis.” Cornea, vol. 30, no. 4, Apr. 2011, pp. 379–87. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181f7f363.

Blog Post: Week 6 Heading link

This week has been an exciting end to an exciting program. This past Friday, everyone presented their final proposals. It was great to see what everyone has been working on and learning over the past six weeks. I am very grateful for this opportunity to learn and for being able to be a part of such a great team.

My main takeaways from this program and advice to future students are the following. First, it’s important to explore as much as you can. Specialties and healthcare delivery can be quite diverse, and certain problems can pop up in some areas but not others. Exploring multiple subspecialties and clinics can expose you to more problem spaces and give you an idea of how ubiquitous a need is. The second is to talk to everyone you can. There are many roles in healthcare and each can provide you with unique and valuable insight into a problem space. Third, I thought it was helpful to write down any words, procedures, conditions, or instruments that I didn’t recognize so that I could look them up later.

I would like to close my final blog post with some acknowledgments. First, I am very grateful for Dr. Jain, Christine Mun, and the rest of the Dry Eye and oGVHD clinic for organizing shadowing experiences and allowing us to learn from them. Their clinic and the impact that they have on patients is amazing and inspiring. I would also like to thank my team for all the hard work that they have put in this summer. I would also like to that Dr. Felder and Dr. Brown for organizing this program. Finally, I would like to thank all of the amazing professionals who allowed us to shadow and interview them.