Chloe Baratta

Chloe Baratta

Basic Information about Student (Small Background introduction)

Year: Senior (’20)

Department: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Areas of Interest: Biomechanics, Rehabilitation, Powerlifting

Contact Information: cbarat2@uic.edu

Blog

An Exploration in Intestines

The first week of anything new is bound to be a tad overwhelming.

No more than 3 minutes into shadowing my first clinical post-op appointment under the head of Hepatology, I realized that, despite taking several physiology classes, I somehow didn’t actually know which vertically oriented segment of the colon was ascending and which was descending. I decided to tackle this knowledge gap issue (and that of the countless acronyms of whose meaning I hadn’t the slightest – ERCP = Every Really Cool Procedure?) by using my favourite resource: Google. I really do think that I wouldn’t have survived in academia before contemporary internet resources simply due to the truly asinine questions I’ve googled on the fly.

This week was jam-packed full of chasing doctors around clinic while badgering them with questions in the hallway between patients, doing my best to imitate a pleasant and ignorable statue (see image) while not getting in the way in slightly cramped procedure rooms when yet again badgering staff with questions, and attempting to adequately document/categorize initial findings of potential areas for improvement.

Findings:

Clinic: Runs mostly like a well-oiled machine, some charting/bureaucratic issues that should be resolved through adoption of new cloud records software within the next year. Issues with patients are fairly common (diet adherence, medication side effects, wound infection, and follow-up attendance are the most frequent themes) along with small time slots for doctors leading to emphasis on most important summary points without explanation of certain items were the over-arching themes I noticed. It also seems odd that disposable stethoscope covers aren’t standard.

Endoscopy Lab: The rooms are cramped and have a lot of exposed wiring/cables/tubes; wiring will be fixed with the incoming lab renovation. Scoping is an actual ergonomic nightmare. The banding device for the scope could benefit from redesign and occludes vision when attached. Similarly, the wire used in ERCPs has no directional tip control or rate feed control and is fairly unwieldy. Inpatient preps for colonoscopies are notoriously poor, possible posited causes could be due to nurse inattentiveness, patient incompliance, or comorbid medical problems. Outpatient preps for colonoscopies are commonly non-ideal but adequate for scoping. The prep solution needs revision as it causes many to throw up and is then ineffective.

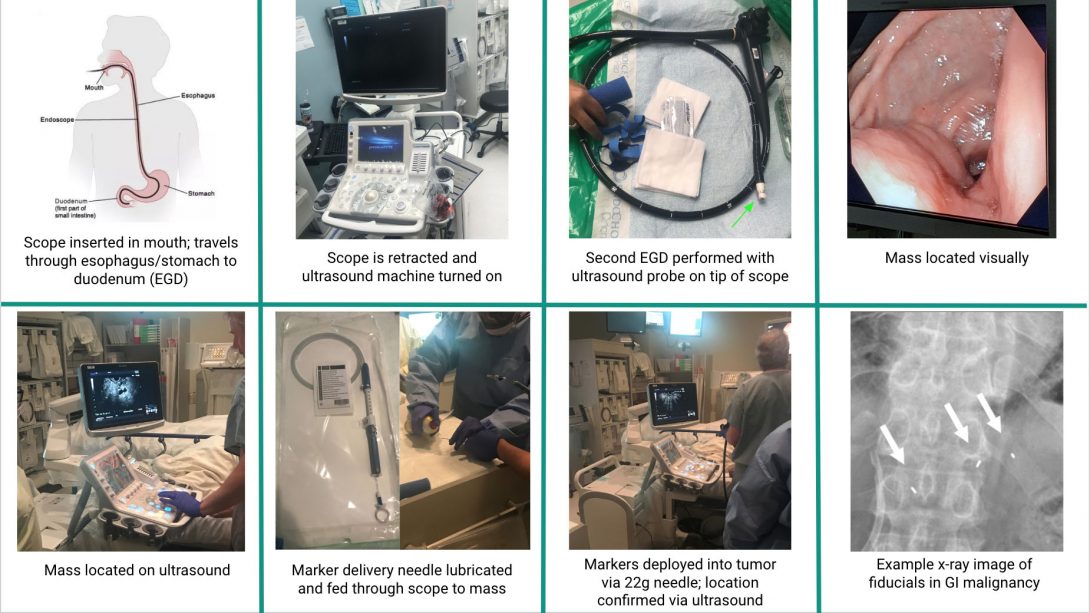

A Holiday Week Shorter than the Existence of the USA

Running into a week bifurcated by the great American holiday, the 4th of July, our team knew we had to be fairly selective with our observations in order to not willy-nilly run off looking at new procedures instead of gathering continued data on procedures we chose to focus on. The beauty of being in Endo Lab is that scoping procedures are all fairly mechanically the same: scope goes in one orifice and stops about halfway through the GI tract. Biopsies, diagnoses, and therapeutic measures may/may not be deployed somewhere in between on withdrawal. The issue begins in finding whether problems are replicated between procedures. As we watched a huge variety of problems in the first week, we realized that some of our targeted “problems” were doctor-specific (operator error) or non-replicable, so we chose to attempt to limit our selection of procedures we watched this week. This led to our storyboard: EUS-guided fiducial placement. I’ll attach the presented storyboard I made below.

Problem identification: Going left-t0-right on each row, we’ll call images items 1-8.

Item 1: Standard EGD problems include varying levels of sedation often leading to patient discomfort, scope tip lubrication (thick lubricant needs to be applied), patient head positioning (bite block is sometimes ejected and airways can be obstructed, both requiring interventional manual manipulation), wire clutter in bed/room, and scope ergonomic design (the hill I will die on).

Item 2: The ultrasound machine isn’t exactly the newest – not that there’s anything wrong with it – but it’s more likely to hold germs/bacteria due to wear and tear on the plastic covering on the keyboard. Procedures aren’t sterile so it’s not really the end of the world, but if it malfunctioned the procedure would be fairly impossible so when machines are updated sanitation might not be a bad concern for redesign. You can do EUS-guided fiducial placement with fluoroscopy too, but it’s more of a complementary technique, not a replacement for US.

Item 3: Having to basically scope a patient twice is a recipe for twice as many potential complications. Here, main concerns are the same as Item 1 with the added potential need for more patient sedation, sanitation of US tip, and lubrication of US tip.

Item 4: As doctors have functioning eyes, visual inspection is considered reliable for locating masses, but it’s not exactly the most exact approach. As it’s unlikely that a patient would have two masses that look identical in the same place with one unnoticed, this method is fairly reliable but just seems funky.

Item 5: The US system is basically magic for a lot of applications but it is pretty terrible resolution and the readings tend to fluctuate a lot.

Item 6: The needle deployment system for fiducials is pretty much guaranteed to need PAM on it. It seems weird that this system would be so poorly designed.

Item 7: The markers don’t really have any control system other than the fact that they’re shot out of a small needle. Orientation doesn’t need to be any specific way so this is fairly irrelevant. Potential complications include migration in the tissue, bleeding, and/or infection.

Item 8: Same pain points as Item 7.

A Tentative Demystification of the Colon

Week Three, or rather, the week the nurses vaguely accepted us as non-horrifying semi-permanent fixtures in the Endoscopy lab was simultaneously fruitful and frustrating. Befriending several of the medical assistants has possibly been the best thing I could’ve done in this program. They’re super happy to answer questions and they take time to volunteer tons of valuable insight during procedures. The same really goes for the nurses, and I may have been slightly too overcome with emotion for 8 am on a Wednesday when one of the charge nurses handed Aga and I print-outs of the biliary/pancreatic duct anatomy so that I didn’t have to covertly google structural minutiae of the liver-ish area while our favourite advanced GI doctor narrated at a mile a minute during ERCPs. I would like the reader to note that he, unlike his colleagues, believes that the bowel likes Def Leppard (not reggae).

Highlights, while not limited to playing Go Fish! (retrieval of a surprisingly phallic-shaped swallowed door hinge from a stomach – see image), were slightly constrained due to a necessary increase in our group meeting time while in clinic. Nevertheless, I was fortunate enough to observe several procedures that I missed in previous weeks (like an EUS) and actually felt like I somewhat knew what I was watching/talking about when asking questions.

While we had what was a bit of the best problem to have – too many identified needs – they desperately required some analysis in order to thin the herd. We initially had SIX needs statements written for the week-end presentation, and only even managed to narrow it down to two top contenders. I’ve thus chosen to discuss one of the black sheep of the needs; rejected for infeasibility/slight scope irrelevance.

Colonoscopies seem to be one of, if not the, most common procedure performed in the lab. Among a massive array of other benefits that well-done colonoscopies impart, a lot of colorectal cancer cases can basically be prevented by routine colonoscopies with polyp removal. Thus, routine high-quality colonoscopies are very important in order to catch these polyps so they aren’t allowed to progress to cancerous masses.

Unfortunately, colonoscopy preps are commonly very poor (particularly on inpatient patients, young people, and the elderly). This leads physicians to have to literally attempt to clean out the bowel with the water jet on the endoscope while performing colonoscopies. This adds a very large time window (often doubling procedure time) onto to usually quick colonoscopies; backing up all cases for the day and often frustrating the physician/staff. As polyps are commonly <1cm, the bowel needs a very high level of cleanliness in order to spot these and remove/biopsy them. The efficacy of the procedure as cancer prevention really plummets due to poor patient preparation. Obstruction of the bowel wall also interferes with pretty much every other efficiency/efficacy aspect of the colonoscopy, let alone the fact that it’s a bit gross. I say just “a bit” because I’ve been strongly desensitized to everything GI/Liver even in the relatively short window of exposure we’ve had so far.

The general physician/staff consensus for the cause of poor preparation seems to be attributed to two main problems: a borderline intolerable prep formula and highly insufficient patient education. Patients tend to throw up or not finish prep solutions all the time (you must drink a gallon of thick, salty, sickly sweet flavoured polyethylene glycol), leading to “completed preps” that basically make it look like the only preparation taken prior to endoscopy was having a solid bowel movement and calling it a day.

When asked what information patients were provided with as to the necessity of properly completing preps (maybe a pamphlet with comparisons of good preps and bad preps and what information can be obtained with both), we were told that patients generally just received (poor) verbal instruction from their pharmacists. It is clear that both the prep formulation and patient education protocols require revision.

As is such:

Problem: poor procedure preparation

Population: patients receiving colonoscopies

Outcome: improved efficiency and efficacy of the procedure

Needs Statement Iteration 1: A way to address poor procedure preparation in patients receiving colonoscopies that improves procedure efficiency and efficacy

Needs Statement Iteration 2: A way to improve poor procedure preparation in patients receiving colonoscopies that increases procedure efficiency and efficacy

Needs Statement Iteration 3: A way to improve poor procedure preparation in patients receiving screening colonoscopies that increases procedure efficiency and efficacy

Revision notes: The edits were mainly petty etymological changes, but the scope was somewhat narrowed in iteration 3 to reflect the emphasis on the need for a good prep to facilitate effective polyp removal to try to prevent colorectal cancers. This is usually done in screening, rather than diagnostic, colonoscopies.

Otherwise Titled: What the Heck Are We Gonna Prototype

This week (the fourth) we were tasked with further analyzing our data within the scope of our needs statement in order to develop criteria and specifications for our project. This process was slightly more frustrating than expected.

We finally narrowed down which problem statement we were going to proceed with! After being split between the ERCP guidewire tech or airway/jaw thrust device until even halfway through this week, talking to almost every single person in the endo lab, and discussing within a group on numerous occasions, we finally sat down and made one of those tables of attributes/ratings (like that seen in lecture) to best objectively select our project. We finally went with the airway device as it had overwhelmingly positive feedback from all levels of care providers (techs -> advanced GI docs) and had the best overall feasibility/desirability/viability/etc rating.

Refining criteria without having a concrete idea of your prototype was extremely foreign to me, so it was an interesting exercise to force myself to design differently. We eventually ended up slightly blending the two methods (design first, criteria after and criteria first, tangible design after) and worked on prototype ideas while brainstorming criteria and specs. We are currently working strongly off of the ideas of past patent applications – there is one product on the market meant to achieve the same goal but it’s overpriced, doesn’t work well, and doesn’t meet our specs/criteria – along with having creative basis, this makes it much easier to get FDA approval if similar to past devices.

This week also really emphasized the importance of being able to communicate scientific ideas to people with varying backgrounds. We split our research in various areas (research literature review, patent lit review, anatomical considerations, mechanical joint design, etc) and regrouped to recap our findings. I am very poor at communicating scientific findings without structured presentations and graphics and I really found myself struggling to informally communicate concepts orally so I’ll definitely be working on that.

Otherwise Titled, "A Brief Tirade Regarding Concept Cards"

Much like Dr. Jung told a very moderately sedated patient who was having immense difficulty during an EGD, we all needed to do some deep yoga breathing this week.

Our penultimate week in CIP was spent solely in the innovation center. I would like to thank the gods above and below for Ground Up; as I have consumed an ungodly amount of coffee from them this week while fighting with Fusion360. I managed to learn a new CAD program on the fly this week (I’ve used it for CAM though, so I am vaguely familiar with…how to import files, as I have the most experience with both CAD and 3D printing in the group and thus took on the duties for both. I designed a series of jaw cups for our device (whew chile it has been a WHILE since I have designed anything that needs to fit the human body and that was apparent), and introduced my group members to the lovely internet resources of open source STL files. I also learned how to use two slicers for two different FDM printers (MakerBot and Prusa) and successfully printed parts/swapped filament (with a bit of help from the lovely innovation center staff) on both. Although I missed being in the hospital, I felt like this was a nice and hands on week in the program (and I didn’t have to wear a blazer)!

This week’s lecture included a fairly hefty amount of group work time, which can be both good and bad. We had a bit of frustration with communication again, same discrepancies with different levels of being “on the ball” with things as previously discussed. The concept card activity was particularly interesting to note variations in how we all pictured our prototypes – we’re basing our design off of some abandoned patents so we have a bit more of a tangible design basis than originally anticipated but somehow we all came up with fairly foreign sketches. I, personally, have a bit of a vendetta against 2D imagery as I am awful at visualizing and digesting it so the concept cards were a bit of a tiny hell to understand and it led to me awkwardly interrogating my group members as to what things meant. Me am dumb caveman. Like model that can hold. Give me modeling clay over pencil/paper any day.