Collin Dreilich

Collin Dreilich

Year: 4th year BIOE student

Area of Research: Pulmonary Critical Care Unit

Contact Information: collindreilich12@gmail.com

Blog

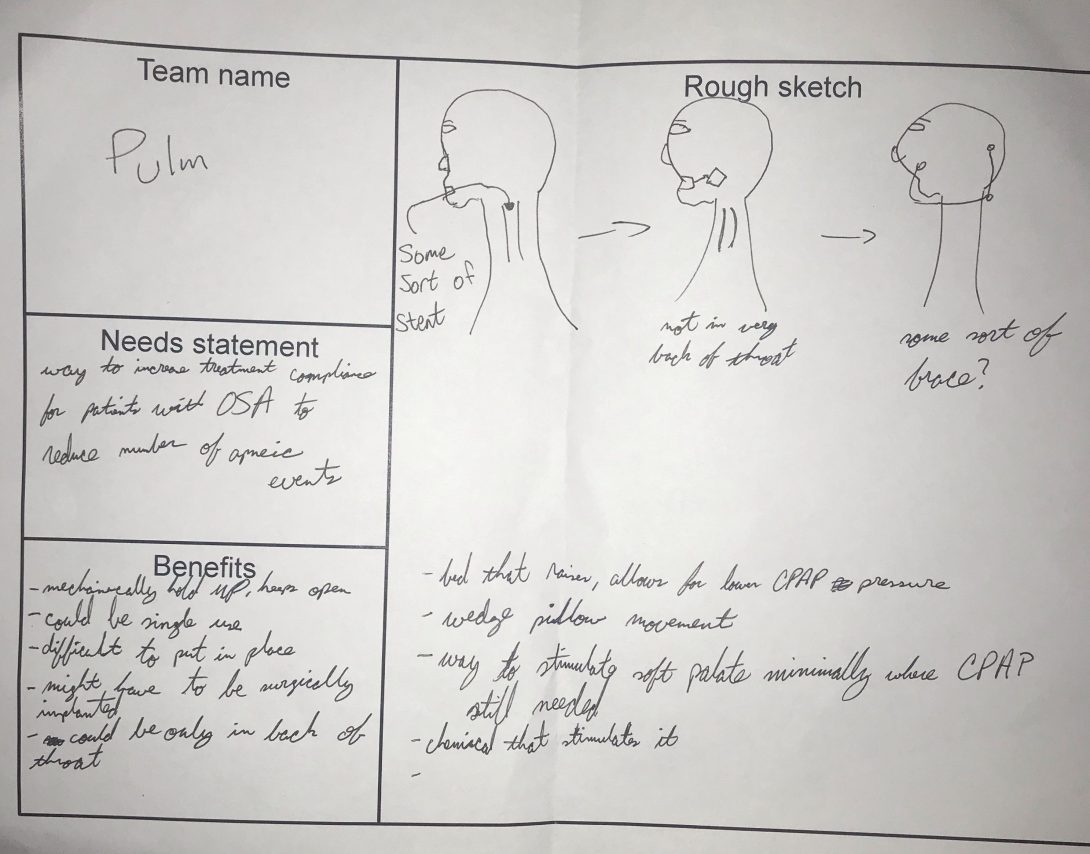

Concept Card Communication

July 28th: Concept Cards

Brainstorming

After working in the clinics for 4 weeks, we’ve realized we want to work on increasing the patient’s compliance rates with their CPAP machines. Considering the compliance rate is ~50%, there has to be a better solution. Speaking to technicians and patients, it seems the reason the compliance rate is so low is the fact the masks/machines are so uncomfortable. Having positive air pressure forced into your lungs while trying to sleep is inherently uncomfortable, which becomes even more uncomfortable the higher the pressure goes.

To create an effective solution, there needs to be specific design and product requirements. Talking as a group, we considered patient comfort to be the most important aspect for our proposed solution. So the device needs to be more comfortable than current options. To achieve this, the device could be customizable for each patient to fit different face shapes or deformities. We could also create something allowing the patient to move more in their sleep. Some current models of CPAP masks look like the masks fighter pilot jets use to breathe. Considering the big tube forcing the air down somebody’s lungs would get tangled up while the patient sleeps, movement isn’t really an option.

As a group, we are still debating on what avenue we would like to go to solve this problem. We’ve had ideas about devices, which are instinctually where our minds go first. However, after brainstorming a bit more, we’ve thought about solutions with the actual machine. An interesting idea could be changing the software on the CPAP machine, allowing for a new setting which could be more comfortable for patients. Design criteria for a solution like this would be more along the lines of making it easy to understand. Giving someone a brand new setting to tinker with that affects their treatment would may require a certain level of intuitiveness to ensure it’s being used effectively.

Considering our many different directions we can go to solve this problem, our design criteria are all over the place. Once we hone in on one type of solution through brainstorming, the criteria will be more clear cut.

3 Iterations of the same needs statement

This week, we are focusing on crafting our needs statements. After shadowing many different departments in the pulmonary critical care unit, I’ve identified a need doctors face while doing bronchoscopies. It can be difficult getting passed the vocal cords when doing a bronchoscopy, especially if the doctor doesn’t have much practice. Many patients become very irritated during this part of the procedure as well, since they are only under local anesthesia and relaxing medications. I noticed often times another doctor will hold the patient’s chin up and apply a subtle amount of pressure, helping to open the airways.

My first needs statement for this problem was: “a method to get passed the vocal cords during a bronchoscopy to make the procedure easier for doctors.” This needs statement had a lot I needed to refine, but I liked the idea I was going for. The scope is fairly general, as “get passed the vocal cords” can mean a LOT of different things. The phrasing is also a little weird, I feel I could get the same idea across without making it seem so cluttered with words. I wanted to hone in on the outcome much more, as I felt the whole statement was too general and could go in far too many directions.

The second needs statement I came up with was: “an approach to mitigate vocal cord irritation in patients during bronchoscopies to make the entire procedure more comfortable.” Now this needs statement has a different outcome and population focus than the first one. I realized while crafting this needs statement, that patient comfort is the reason it can be so difficult to get through the cords. If patients are more comfortable, it’ll be easier for the doctor performing the procedure while not as taxing on the patient. I think this needs statement has a better scope and focuses on the “actual” problems there, rather than the low hanging fruit problems. The outcome can be refined though, as it feels sort of weak and rushed to me.

My final needs statement was as follows “an approach to mitigate patient vocal cord irritation during bronchoscopies to enhance procedure efficiency and increase patient comfort.” This needs statement feels like it has the best problem stated, population, and outcome of all three. After talking to the doctors doing the procedures and seeing them, efficiency seems to the best word choice. I noticed on multiple occasions where the doctor would attempt to enter the airways but the patient would be too agitated by the scope, so lidocaine (a local anesthetic) would be administered onto the vocal cords. The doctor would then need to wait about 1-2 minutes for the effects to kick in, so we would all just be standing around watching. Sometimes, this needed to be repeated 2 or 3 times. On procedures that can last up to an hour, saving those couple of minutes in the beginning eases the patient’s mind and mitigates time during an uncomfortable procedure. Patient’s really don’t seem to enjoy this procedure, so making them as comfortable as possible should help everyone in the procedure room. This needs statement focuses mainly on patient comfort, and has grown drastically from the first iteration drafted.

Step 1

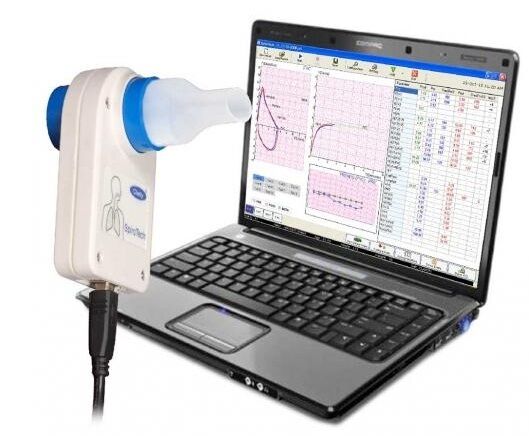

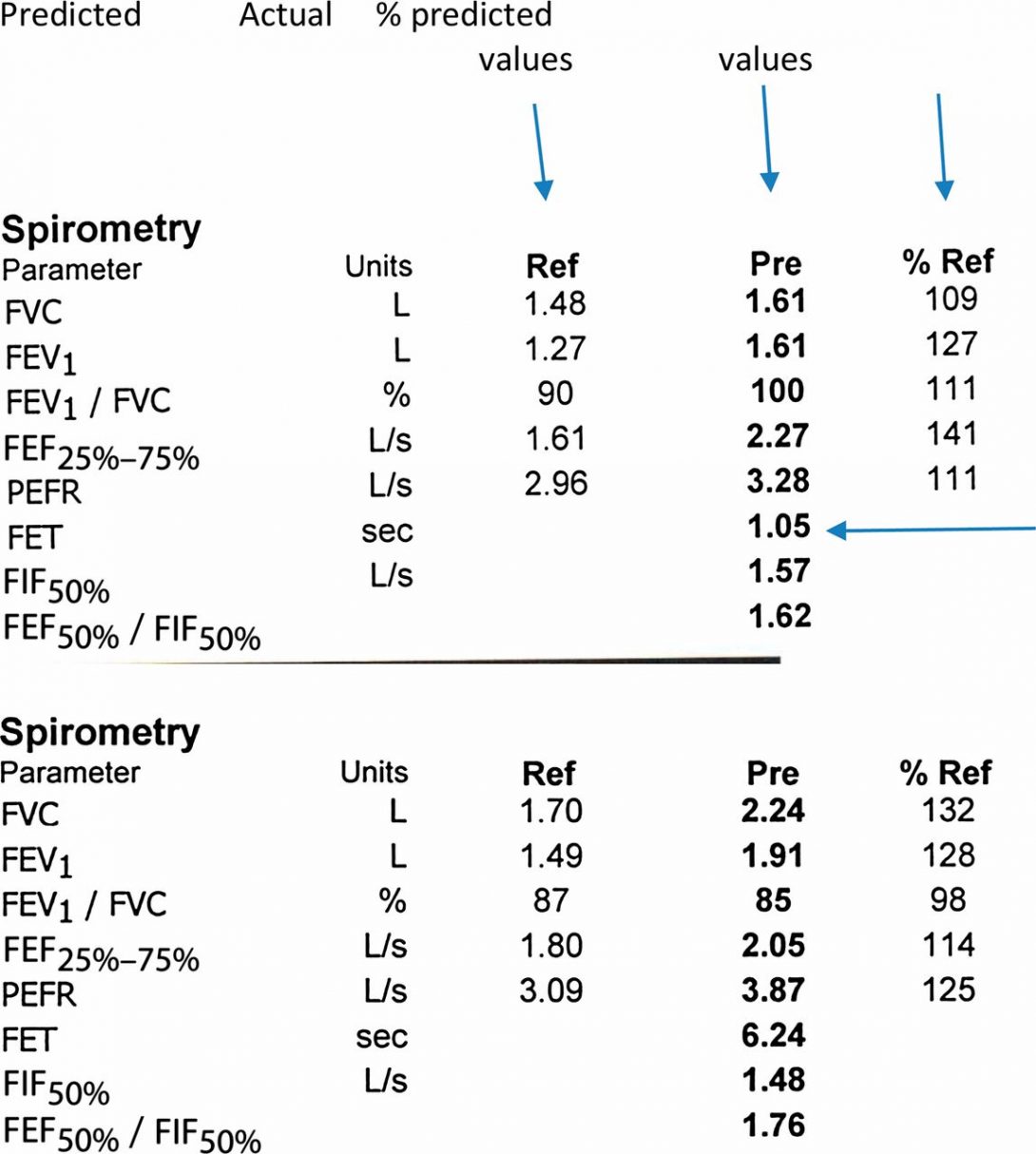

The first step consists of the technician setting up the spirometer, entering specifics of the patient like their height, weight, race, and age. This tells the software what to base the results against.

Potential “pain points”: What if incorrect specifics are entered and the test is completed? Do specifics need to be entered every time for repeat patients?

Step 2

July 8th: Storyboarding

Step 3

The procedure is then done. The technician places a nose clamp on the nose to ensure all the air inspired/expired goes through the patient’s mouth and into the machine. The technician motivates the patient throughout each procedure, essentially coaching them throughout it. Multiple trials are conducted, while the technician looks for repeatability by the patient.

Potential “pain points”: What if the nose clamps don’t fully plug the patient’s nose during the procedure? How would a technician or patient realize if it isn’t fully plugged? What if the patient becomes exhausted during the procedure and can’t reproduce the same results multiple times? How long is the patient allowed to rest between trials? What if the patient mishears the technician when coaching?

Step 4

The technician then administers an inspired bronchodilator, meant to open the airways and make breathing easier. Three separate breaths are taken by the patient, each held for 10 seconds then released. Once the medication is given, the patient needs to wait 10 minutes while it takes full effect. During this time, they are left alone in the room. If a patient does not know how to use an inhaler, the technician teaches them how to do it.

Potential “pain points”: What if the patient does not take the medicine correctly? Could the patient be bored waiting alone in an admittedly bland room? Does the technician need to set something else up during these 10 minutes of waiting?

Step 5

The same procedures done in the step 3 are done, with the technician coaching the patient throughout it again.

Potential “pain points”: What if the clip does not fully plug the nose? What happens if a patient coughs while doing the procedure? What if the spirometer is at an uncomfortable angle for the patient?

Step 6

The final results of the procedure are printed out for the technician and patient to see. The technician logs out of the computer and reviews the results with the patient. Both the patient and the technician keep a copy of the results. The machine may make an interpretation based on the data, subject to a physician’s review.

Potential “pain points”: Seeing the interpretation, patients may become scared from terms like “possible obstructive airways”. Although it isn’t a diagnosis, patients might not fully understand that. Having multiple trials on the same graph can be difficult to distinguish between each one. Logging out of the computer after every patient means they must be logged back in with their own unique login and password for the next patient.

What was good design and bad design you witnessed?

After the first week of shadowing around the pulmonary department at the hospital, I noticed how many things got done. Specifically in the sleep apnea clinic, patients seemed confused when being taught how to use the monitor for the sleeping test. All instructions were verbal, and they lasted roughly 5-6 minutes in total. I think written instructions to send home with the patient would help them understand clearer. Patients also complained the CPAP machines could be very uncomfortable in the night. In the ICU, the hallways were very cramped during rounds and clinicians were straining to be fully involved with each patient. This inhibited learning, and seemed to slow down the overall flow of the rounds. Not everything seemed like it needed improvement, however. In the outpatient clinic, the doctors and pharmacists asked the same questions to the patient independently, often times receiving slightly different answers which helped paint a fuller picture of what the patient was actually doing. I also noticed a biometrics fingerprint scanner in the ICU to obtain medicine from the locker. It kept a record of who opened the locker and knew what medicine was taken out, which seems like smart security to me.