Lander McGinn

Lander McGinn

Year: Medical school 2nd year

Area of Research: Gastrointestinal department. Previous research done in immune system development. Current research in ophthalmic biomaterials, and student satisfaction regarding medical school curriculum.

Contact Information: lmcgin4@uic.edu

Blog

First Week on the Job

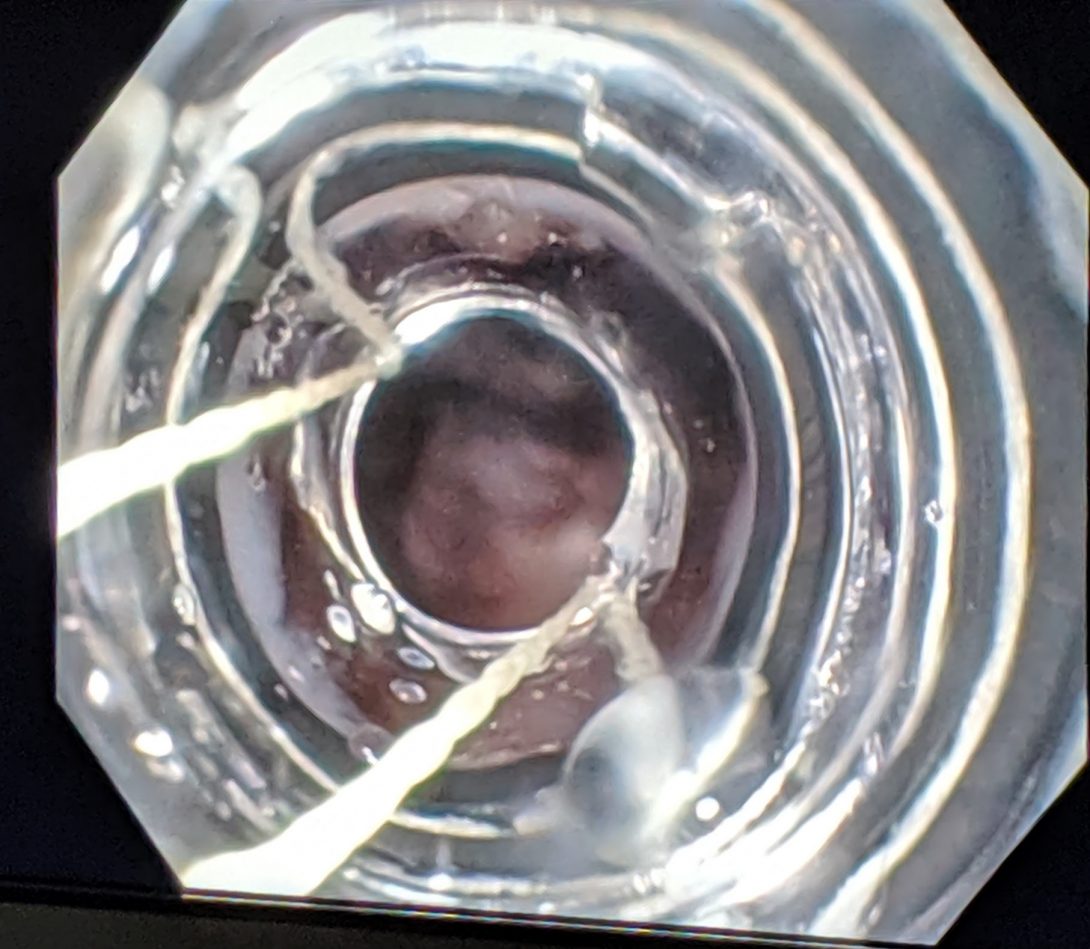

In our first week working in the gastroenterology department, we observed procedures that dealt with the gastrointestinal tract and the liver. During this time, our conversations with physicians and other members of the healthcare team revealed numerous opportunities for improved design. One among these that stood out is the current method of managing esophageal varices using ligating bands. Varices arise most frequently from cirrhosis which results in portal hypertension. Long story short, this results in blood backing up into the veins of the esophagus and can get so engorged that they may even rupture. This rupture has the potential for massive hemorrhage and death.

The ligating bands used for varices are launched from an accessory affixed to the end of the endoscope. The design of this accessory fails many aspects of the AEIOU framework. Simply attaching the accessory seemed cumbersome because the user (the doctor) often cannot see if it is secure. In this way, it causes uncertainty and confusion for the user, which places the patient at risk. The environment is inherently compromising for the patient since the bands are being launched at vulnerable tissue. If the procedure goes poorly, and the user damages the tissue, they can inadvertently cause the worst-case scenario that they are trying to avoid. The object, the accessory, itself, seems it could be improved. Before the procedure even begins, the field of vision is severely limited, and it only gets worse throughout the procedure as debris and secretions occlude the entire apparatus.

While the aforementioned device seems like a promising area of improvement, it is important to note also the instances of highly successful design. The process of disinfection and management of the scopes has been well thought out. There is a dedicated space for the cleaning with ample room, wherein the worker follows a specific set of guidelines. Thus, it is relatively comfortable and not confusing. The worker is able to manage their space at a pace that suits them and scopes are taken in and out as needed. The process has a multitude of checkpoints to ensure safety and that procedures are followed accurately. As well, there is a yearly evaluation of competency for the worker. While endoscopy sanitation associated infections have been an issue at other hospitals, it has never been an issue at UIH.

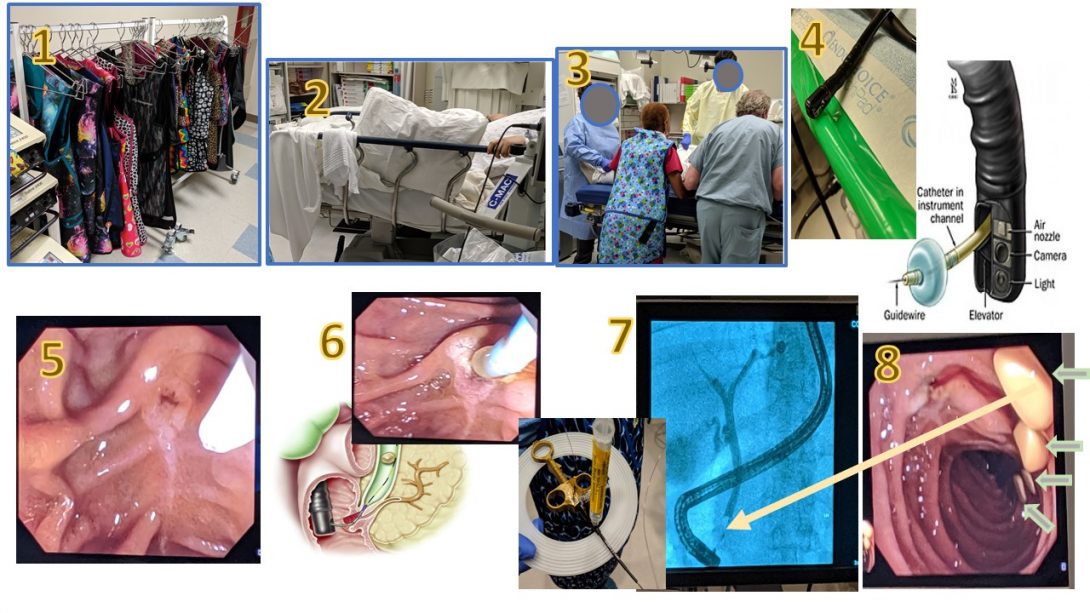

Storyboard for ERCP-guided removal of four gallstones

During this second week, we had the opportunity to observe an ERCP-guided removal of four gallstones. A 26-year old patient came in with suspected acute pancreatitis and a history of gallstones, which had been confirmed with previous imaging studies. At this point, Dr. Boulay decided it would be best for the patient to have the stones removed. This storyboard aims to explain this process visually.

All these images have been obtained in the University of Illinois at Chicago Endoscopy Lab with permission of Dr. Brian Boulay with respect to HIPAA guidelines and patient privacy.

Source of sphincterotomy diagram

Explanation of steps

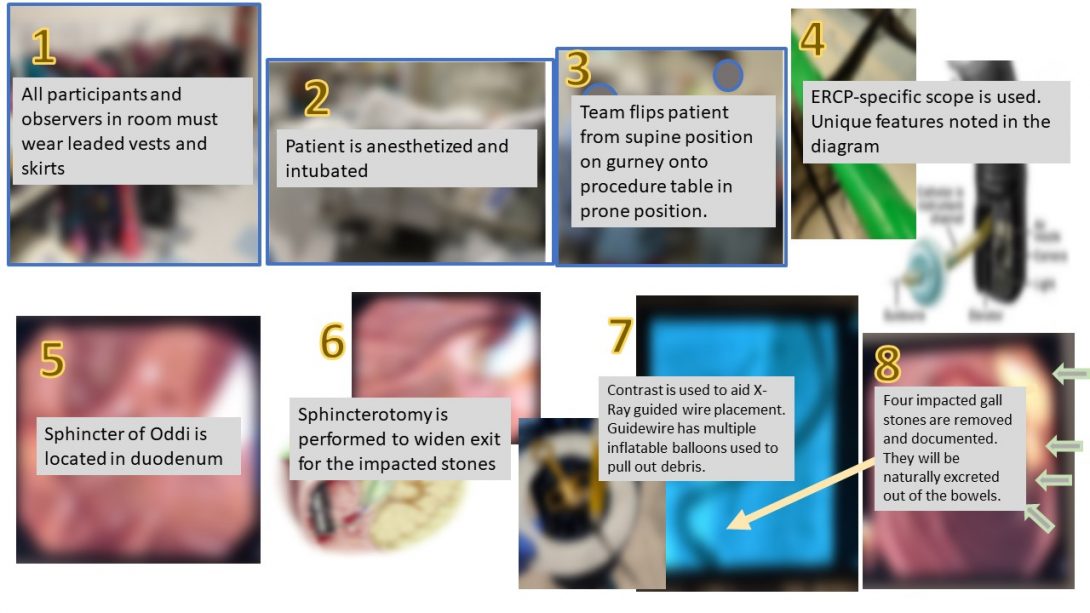

In this next image, the images have a brief explanation in a text overlay.

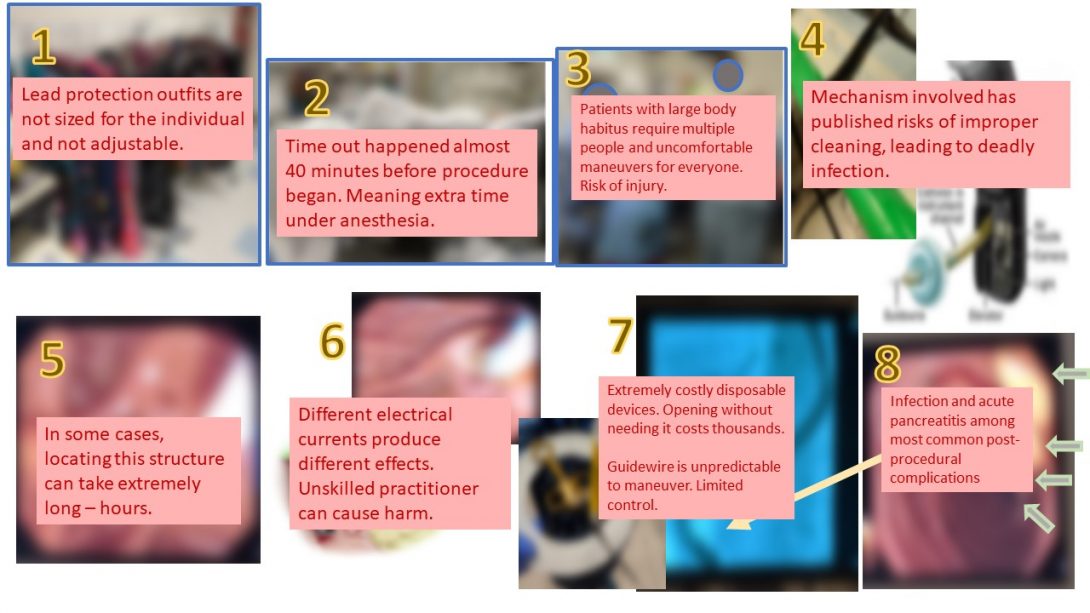

Pain points

One of the functions of this storyboard is to also identify pain points inherent to the procedure. I have interpreted these pain points to be possible health complications unique to the procedure as well as difficulties in performing the procedure.

Crafting a needs statement

The focus of this week is to begin crafting a needs statement. The following needs statement is an example of the thought process involved in creation of such a statement. It is unlikely that this will actually be the focus of our project in the end. A needs statement involves 3 components: a problem, a population, and an outcome.

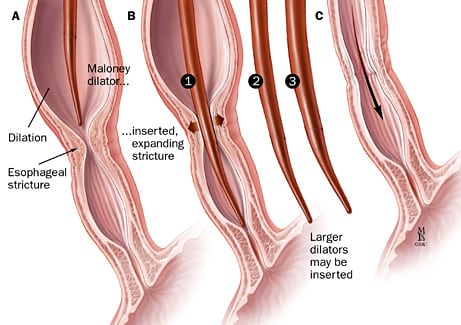

Iteration 1: A way to dilate the esophagus quicker in patients with esophageal strictures so that time between treatments is reduced.

- One problem we identified is the time between dilation treatments. The current practice is to dilate by about 2 millimeters every few weeks. This measurement does not seem to have a well-researched basis, and is founded on what seems to have been safe for patients and worked in the past. So, a timeline that is shorter and perhaps dilates more each session, if the esophagus allows it, would be better.

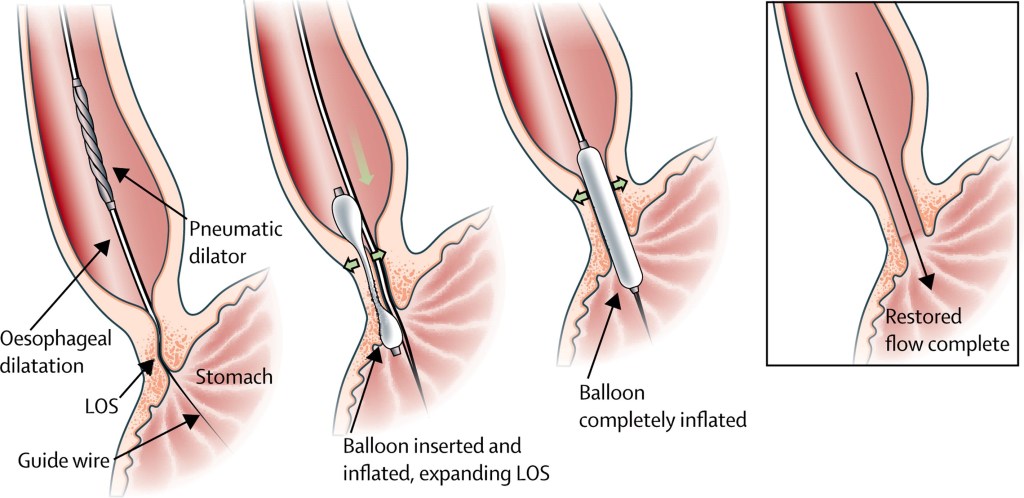

Iteration 2: A way to manipulate the physical properties of the esophagus in patients with esophageal strictures so that the time between balloon dilation treatments is reduced.

- This next iteration broadens the scope of the problem to allow us to think of other means of approaching the problem. Changing the problem to instead “manipulating the physical properties” means that we can consider the physical limitations of the tissue as our focus, instead of focusing on the procedure.

Iteration 3: A way to manipulate the physical properties of the esophagus in patients with esophageal strictures so that the time between dilation treatments is reduced.

- In this iteration, I have eliminated “balloon” before dilation treatments. My logic is that there are different methods of achieving dilation, which are illustrated in the images below. Balloon dilation, ergo, may not be the best option for all patients.

Common balloon dilation for esophageal stricture

Below is the more common method of esophageal dilation using a balloon to dilate.

Conceptualization

This week, we had to pare down all of our ideas about what we could potentially improve in the GI department. We had ideas ranging from esophageal varices ligation mechanisms to improvements on patient education for colonoscopy prep. After running through several brainstorming exercises as a team, however, we decided upon a device that could be used to minimize the risk of complications during an endoscopy.

Normally, an endoscopy is a fairly straightforward procedure. The patient is sedated to a point that they are responsive to binary questions and they are breathing autonomously, but they are extremely relaxed and able to endure the scope passing down their esophagus. However, if a patient has underlying obstructive breathing disorders like COPD or asthma, they can start to cough and gag and “desat,” meaning the oxygen in their blood is decreasing — they are essentially suffocating. The nurse who is administering the sedatives and ideally monitoring vitals must then step in and perform a chin-tilt-jaw-thrust maneuver to try to open up the patient’s airway. This involves a nurse standing at the patient’s head and manually pushing their jaw up and out to widen the space air can pass. Unfortunately, this means the nurse must maintain this position for quite a while — in one instance up to about 20 minutes. If the patient’s oxygen level does not increase, they must be advanced to anesthesia and intubated.

There are several issues present here: the nurse performing the maneuver is now locked into that position and unable to assist in any other way — more staff must be brought in. As well, if the patient does need to be advanced to anesthesia, then that introduces other health risks. Finally, the physical demands on the nurse performing the maneuver as well as the burden of having so many people being brought into the equation lead our team to believe that this would be a valuable area to improve.

With this all in mind, we seek to develop an airway protection device that could be placed on a patient suspected to be at risk, and then if a complication should arrive, the device would be simply clicked into place and would essentially perform the jaw thrust maneuver in stead of a nurse. This minimizes the need for additional personnel, and would hopefully help avoid having to advance a patient into anesthesia.

In terms of qualifications for our device, it must have the following qualitative criteria:

- Device should be disposable

- Device should be portable

- Device should not cause prolonged harm or strain to patient

- Device should be low cost

- Device should take no longer than 1 minute to set up

- Device should be intuitive to use by anyone in the procedure room

In terms of quantitative and measurable criteria, our device must meet the following:

- Device should maintain selected end-range positioning

- Device should be rapidly adjustable for anatomical variation

- Device should not require power

- Device should not apply more than 17N of force to either jaw

- Device should not apply more than 14N of force to mental protuberance

Concept Cards

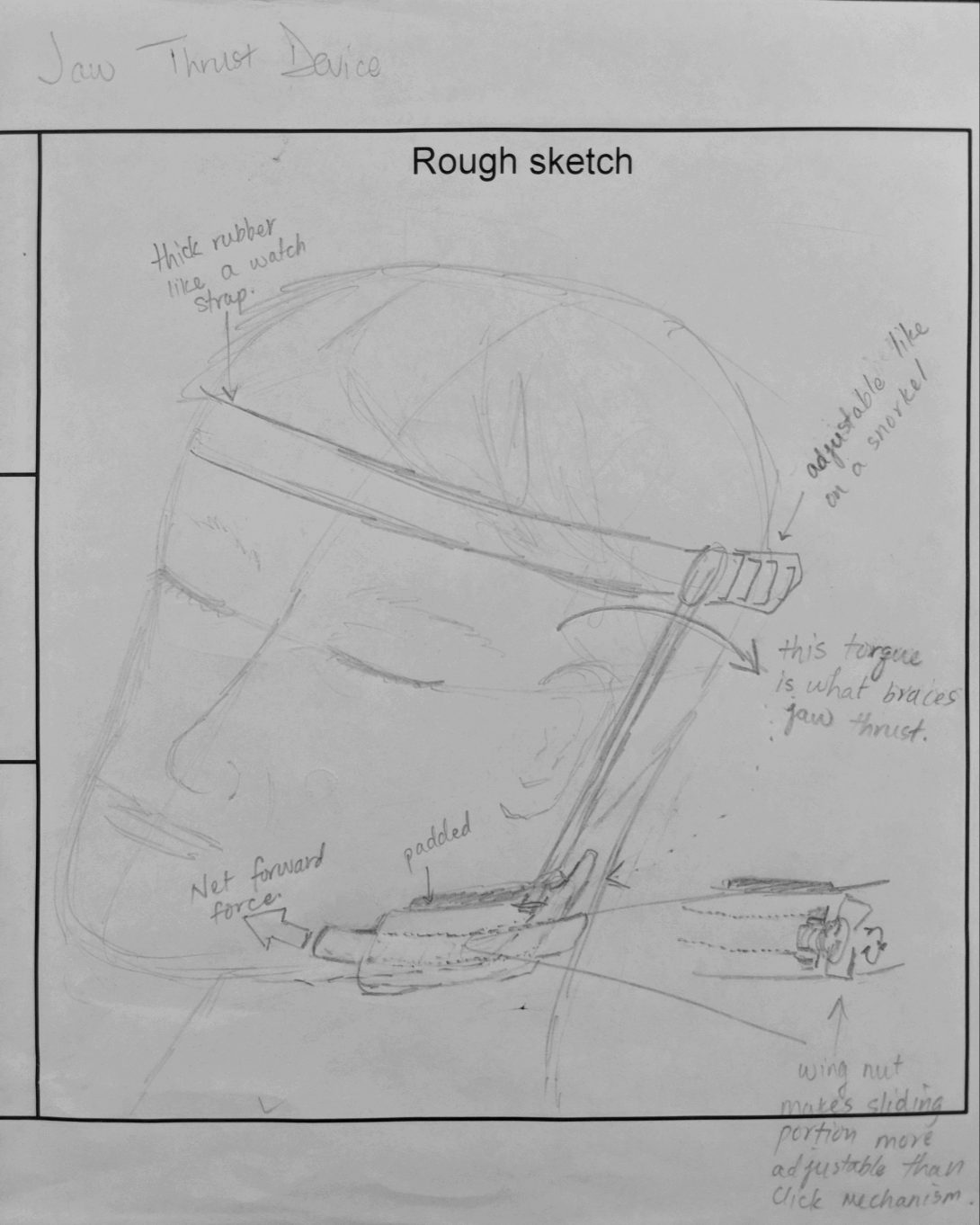

In this week, we were charged with creating concept cards as a means of focusing our thoughts in order to better present to our mentors. In this exercise, we had to sketch our device to give some sort of visual which we would show. In our version, we tried to create a device which might mimic the action of a jaw-thrust maneuver. Previous blog posts have discussed the need for such a device, but in short, we wanted something that would minimize the physical burden on staff who would otherwise have to stand at a patient’s head and hold that position for upwards of 15 minutes. This position means that a nurse cannot perform any other duties for the time they are holding the position, and it can leave them feeling exhausted.

Our device would hopefully maintain a patent airway especially for a patient with underlying obstructive airway disease or sleep apnea without the need for staff to physically hold open the jaw. Such a device minimizes the need for additional personnel and aims to increase patient safety, while avoiding the necessity of advancing a patient from moderate sedation to anesthesia in the case of an intubation.

Filling out this concept card allowed me to get the highlights of our device clear in my head. It gave me sort of an “elevator pitch” that I could quickly present to someone. Below is the beginning of what would be a more refined concept card.