Zafar Siddiqui

Zafar Siddiqui

Basic Information about Student (Small Background introduction)

Year:

Area of Research:

Contact Information:

Blog

Pulse Ox

This week was interesting because we delved deeper into some of the needs we’ve previously identified. It was also interesting to see that some of the needs we identified were only needs in hospitals like UIH, where sometimes funding was the issue. For example, we spent a lot of time identifying problems with the bronchoscopy suite, but when we did our own research, we found out that solutions to most of these problems exist. At UIC, the physicians were simply using older bronchoscopes, and we confirmed this with the physicians there.

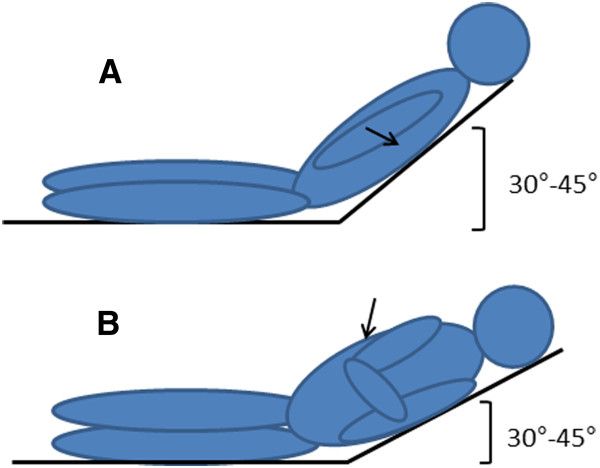

We also identified a new problem, however. A problem that is somewhere in between evolutionary and revolutionary. It would expand the scope of old technology but would have an extremely high impact. This need was a way to measure central oxygen saturation levels. This need was brought to light when we found out that it is hard to obtain a normal pulse ox reading, normally from the finger or another extremity, in sepsis patients. Septic patients experience vasoconstriction of their peripheral arterioles, and thus, it’s peripheral oxygen saturations are hard to obtain. At the same time, these patients are assumed to have low oxygen saturation but can still be undertreated for this, or sometimes can be overtreated as well. Overtreatment would also produce its own problem with oxygen associated tissue injury. The reason pulse ox work on extremities is because it depends on light transmission through the skin and tissues, as shown in the picture.

We’ve thus crafted this understanding into a few iterations of a needs statement.

- A way to obtain a central O2 saturation value in all patients in the hospitalThe rationale behind this needs statement is to not limit ourselves to only dealing with one subset of population, and to focus on a specific problem that if solved, may be widely applicable to many patients.

- A way to obtain a central O2 saturation value in septic patients in the hospital.This needs statement is the most specific and has the narrowest scope of all three. The rationale here is to focus on a specific problem as seen in a specific subset of patients in the hospital.

- A way to obtain an accurate O2 saturation value in sepsis patients in the hospital.The rationale behind this needs statement is to make the problem a little broader than the last one. Perhaps a central O2 saturation value isn’t the solution to accurately measuring O2 sats in a septic patient. On the other hand, this needs statements focuses on septic patients in the hospital.

Thoracentesis

This week was all about storyboarding. We broke down several processes into individual steps and focused on possible pain points in the process. This exercise was very enlightening. Below is my storyboard for an aborted thoracentesis procedure.

2: 44 PM: The patient is brought down into the pulmonary procedure suite.

Possible Problems:

- If the patient is in the ICU, the protocol doesn’t allow them to leave so the procedure must be done in an ICU room that’s not specialized for this kind of procedure.

2:51 PM: The team of an attending, a couple of fellows and residents, as well as a technician, prepare the patient for the procedure by rolling the patient over.

Possible Problems:

- It takes a while for the patient to be put into position and I wonder if, during the procedure, he may change his position on accident.

2:53: The attending uses an ultrasound probe to find the pleural effusion so that he can drain it.

Possible Problem:

- Most of the fellows/residents arent’ very comfortable reading lung ultrasounds and don’t know what to look for.

2:53 PM: “The fluid doesn’t account for the X-ray findings,” he says. He then asks the team what could possibly have lead to the X-ray and US being so different. The pulmonary technician answers.

Possible Problem:

- Much time was “wasted” prepping the patient and the team for a procedure that didn’t happen. (Couldn’t they have done the ultrasound earlier??)

2:55 PM: The procedure is aborted and bronchoscopy is scheduled for Friday.

Possible Problem:

- The patient barely has a left lung because of this condition. While he’s not acutely short of breath, the patient has to wait for two days for a procedure that takes 10-15 minutes

- The patient had been given food/juice before the procedure so a bronchoscopy couldn’t be done at the same time.

First Week in CIP

It has been quite an interesting week, and I can’t believe we’ve seen so much in a week’s time! We’ve rotated in the ICU, pulmonary outpatient clinic, pulmonary hypertension clinic, sleep clinic, and the pulmonary function test lab. Each environment was so unique, and each was replete with opportunities for improvement. On our first day, we met our mentor Dr. Dudek, and given how busy he must be, I was pleasantly surprised by how personable and invested he was in our success in this program. He made it clear that he’d be willing to help us along the way and provided us with a detailed introduction to the field of pulmonary/critical care. We then went to the ICU and familiarized ourselves with the environment before heading to lunch. In the evening, we were in the outpatient clinic. Unfortunately, there were only a few patients that day. However, there was still plenty to soak in, from the workflow to the environment. On Wednesday, we walked to the sleep clinic. This was possibly our best experience of the week. The staff was so helpful and we got to meet with every single kind of employee in the clinic, including the clinical coordinator, the attending, the fellows, the respiratory therapist, and several more people! Each person allowed us to shadow them and fielded any questions we had. The PFT lab was our destination for the evening and it was a large room filled with cool technologies that allowed patients to be screened for respiratory problems. On Thursday, we got to see the pulmonary hypertension clinic, where Dr. Fraidenburg and the nurse were both very helpful in showing us all of the sophisticated technologies their patients use to take their medication. Finally, on Friday we got to spend significant time at the ICU. We shadowed the ICU rounds which was a scene unlike any I’ve seen before. It was fascinating as both a medical student and an engineer. I think we’ve come up with almost 100 problems so far in one week, and I look forward to spending more time finding more creative ones in the weeks to come.

So we saw a lot. Good examples of technology and processes, and not so good ones. Some examples of good execution were the ultrasonic nebulizer technology which was very user-centric, the nature of the interactions in the ICU, the efficiency of the sleep clinic, and the PFT lab. The ultrasonic nebulizer came with several ways to charge the device, the battery lasted the whole day, and it was very portable. Additionally, the company sent each customer two units. In the ICU, so many different people interacted seamlessly in very large teams to take care of very sick and complicated patients. The sleep clinic was relatively small for how many patients they had, but each bit of space was being used and the staff there also worked great as a team. The PFT lab had a lot of cool tech, and the staff was very helpful in instructing the patients on how to complete their tests accurately.

Then, there was the not so good. Like a lot of it. Some that stand out was the fact that the CPAP/BIPAP masks weren’t customizable. People with angioedema, facial deformities, or with any other reason their face isn’t like the average person’s had trouble using the mask. This means their sleep apnea can’t be treated optimally. Additionally, the positive air pressure was very uncomfortable and there was no way to only turn this on once the patient fell asleep. The technology for the stress testing in the PFT lab seemed old and boring, so people may have a little bit less motivation to push themselves to the limit. The WOW’s (workstations on wheels) in the ICU were very cumbersome and crowded the already small hallways even more. Also, everyone on rounds had stacks of papers, and sometimes when a medical question was asked, there was uncertainty because it took some time to look at patient’s charts to find small, but relevant details.

I think we're a little crazy

This week began with the task of picking a needs statement to focus on for the next three weeks. This was a painstakingly frustrating process as we kept bouncing around the 3 needs statements that made our final list. We interviewed several physicians and other healthcare experts. Finally, we stumbled onto Dr. Haas who saved the day. As an interventional pulmonologist, two out of our three needs statements were in his exact area of expertise. He explained to us that one needs statement may be very complicated and slightly out of scope in terms of the timeframe for the program and the knowledge required to understand the technology. The other need had actually just recently been solved. We sketched out a few of our brainstormed ideas to him and he was very impressed because our sketches were very similar to two patents that have been filed to address this exact need. It turned out were a couple of years too late. While this would be disappointing news to some, it was fulfilling to hear him tell this to us because it could be an indication that we’ve learned a little bit about the innovative process these past few weeks.

So then we were left with one needs statement, and we modified it to make the possible scopes larger. We then identified design criteria that we would want our innovation to have, as well as product specifications. We spent some time searching the literature to come up with product specifications that could measure our innovation’s level of success.

We then brainstormed different avenues to solve the problem and then spent many hours thinking of possible solutions within each avenue. We came up with some crazy stuff, no doubt, but the exercise was the most fun I’ve had so far in the program. One of the ideas we liked the most as a group was an idea of a sleep tent that would not only remove the nuisance of wearing a mask but could possibly help insomnia symptoms as well if the tent was made to be conducive to sleep. This concept of possibly treating insomnia and sleep apnea together was fascinating, especially since 50% of sleep apnea patients also have insomnia. The sleep tent idea we came up with would be able to make an airtight seal through which positive pressure would be applied and the entire tent would become a high-pressure atmosphere to sleep in. Companies such as Hypoxico already market tents to do the opposite, that is, lower the pressure and simulate high altitudes and low levels of oxygen. These tents are marketed towards professional athletes. Repurposing this kind of design for sleep tents to treat sleep apnea was one of the many interesting ideas we came up with.

It's starting to get real....not really

This week was all about picking a solution and ironing it out. We started the week with four possible solutions. As a group, we decided to ideate the most exciting one first, although we were all quite cynical of the tech being able to actually work. Our problem was CPAP compliance, and we thought that creating pressurized sleep tents would be comfortable and treat these patients’ conditions. But we were wrong, and we realized after many hours that it just wouldn’t work because of the laws of physics and physiology.

So we moved on, and we decided on focusing on creating a system that builds on existing tech. In order to firstly ensure that we knew the details and benefits of our concept, but also to be able to show others, we began to create concept cards. Concept cards are really useful to give a general but powerful overview of the idea that you are proposing. It allows stakeholders to envision the impact it would have while also explicitly pointing out the benefits to them. We also used it to ensure that we were not only thinking through our ideas but also to make sure that we were keeping the stakeholders and users in mind while we were doing it.